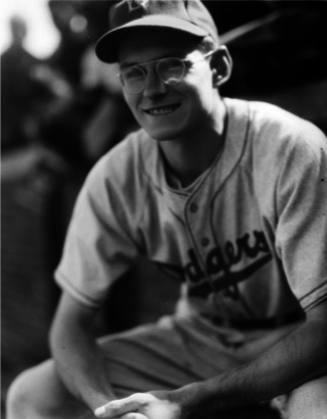

Eddie Basinski

Eddie Basinski always conceded that he never looked much like a baseball player. He sported a slender frame and bottle-thick steel-rimmed classes, prompting many fans to view him as a Mr. Peepers in flannels and Brooklyn Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey to describe him as “the escaped divinity student.”1

Eddie Basinski always conceded that he never looked much like a baseball player. He sported a slender frame and bottle-thick steel-rimmed classes, prompting many fans to view him as a Mr. Peepers in flannels and Brooklyn Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey to describe him as “the escaped divinity student.”1

“Inside, I had the same competitive fire that Michael Jordan, Lou Gehrig, and Joe DiMaggio had,” Basinski once told an interviewer. “I just didn’t look the part, and people didn’t like it.”2

But they loved the view when Eddie Basinski played baseball. Although he didn’t get much of a shot at the major leagues – he played in 203 games with the Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates in 1944-45 and part of 1947 – he was a minor-league legend good enough to make the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame, an accolade he earned mainly because of his slick fielding, which was the result of his remarkably quick reflexes.

Apart from Basinski’s scholarly, if not dweebish, appearance, the other thing that stamped him as a baseball odd duck was that he came to the game as a trained – starting at age 5 – classical violinist who occupied a chair in the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra, earning him the nickname “The Fiddler.” As a college freshman, Basinski played in the last chair. By his junior year, he had challenged and outplayed 40 other violinists to become a concertmaster.

For all of his natural musical talent (he was also a near virtuoso on the piano), Basinski didn’t have much when it came to baseball. But he practiced baseball fundamentals as religiously as he practiced the violin, which was the main reason he ultimately carved out a 16-year professional career, most of it with the Portland Beavers, some of it with the Seattle Rainiers.

Edwin Frank Basinski was born on November 4, 1922, to Walter and Sophie Basinski, part of a large working-class Polish family in Buffalo, New York. He had two older brothers and four younger sisters, according to the 1940 US Census. His father, Walter, a former Navy man who plied his trade as a machinist, ran his house like a military encampment. At age 4, Basinski had scarlet fever, which caused his terrible eyesight – 20-800, according to Basinski.3

Walter believed that if Eddie was going to make anything of himself in life he needed an honest trade. Further, he considered baseball a frivolous waste of time that had no place in his son’s development. Eddie thought otherwise, but had to sneak out of the house just to play and risked a whipping if his father found out.

Through considerable cajoling, Basinski ultimately received his father’s permission to try out for his high-school baseball team, but failed to earn a spot because the school’s coach, Pop Yerke, couldn’t conceive of a skinny, bespectacled kid like Eddie playing ball.

So Basinski took to the Buffalo sandlots, playing and practicing with a small core of players that included future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn, one of Basinski’s closest childhood friends.

“The city park was next to the street I lived on,” Basinski told author Craig Allen Cleve, who wrote Hardball on the Home Front: Major League Replacement Players of World War II. “There were five aspiring baseball hopefuls who practiced every day there. We rotated our practices so that each player got 30 swings of batting practice. We were able to complete the rotation three times before it got dark.”4

If no one else showed at the park, Basinski still had his own training routine. He practiced baserunning and sliding and even stood a bat on end in front of the backstop, and then went into the outfield to practice making throws at the plate. “I had something going for me in baseball,” Basinski told Cleve. “I was quick on my feet. I could leap. I had long arms. I thought this is it for me. There isn’t any other way. For me, it was trying to find some way to gain some sort of recognition, so I wasn’t just one of those Polish punks over there from Kaiser town in Buffalo. None of us were going anywhere. Sports was the only avenue I had at that time.”5

Basinski didn’t play baseball at the University of Buffalo, either, because the school, although it had an excellent engineering program, had no baseball team. So Basinski lettered in tennis and cross-country and continued to practice baseball, hoping to play one day in one of Buffalo’s semipro AA leagues. In 1943 Basinski earned a degree in mechanical engineering and went to work for the Curtiss-Wright Company in Buffalo, one of the country’s leading aircraft manufacturers and a primary producer of US warplanes, including the P-40 Warhawk and the C-46 cargo plane.

Also in 1943, the 6-foot-1, 175-pound Basinski finally broke into Buffalo’s AA league, playing shortstop and batting cleanup, and people began to take notice of his superb fielding and timely hitting. Dick Fisher, who owned a Buffalo sporting-goods store and bird-dogged the city’s sandlots for major-league teams, lobbied on Basinski’s behalf. At the end of 1943, an all-star team composed of Buffalo’s best AA players, Basinski included, assembled to play similar teams in New York and Pennsylvania. One such outfit from Oil City, Pennsylvania, boasted a 19-game winning streak. Fisher persuaded Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey to send a scout to the Buffalo-Oil City game.

Buffalo hammered Oil City, 9-1, with Basinski delivering a two-run triple and pair of three-run homers, accounting for eight of his team’s nine runs. A perfect performance under perfect circumstances resulted in the Dodgers signing Basinski to a contract that included a $5,000 signing bonus. Basinski joined the Dodgers for two weeks in early 1944 so that the club could take a look at him and figure out at which minor-league level he ought to play. At the end of the two weeks, with the Dodgers at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, manager Leo Durocher called on Basinski to bat eighth and play second base. The date was May 20, 1944. Basinski had not played baseball in high school, college or the minor leagues, and had only one limited season in a Buffalo semipro league.

Ripley’s Believe It or Not called his jump from semipro ball to the majors “a 10 million to one shot.”6 In his second time up, Basinski looked at Reds left-hander Bob Katz’s first pitch and drilled the second one off the wall in left for a triple. After he nailed a runner at first by ten feet and handled seven chances, Durocher began calling him “Bazooka.”7

By the first of June, Basinski was hitting better than .300 and making both Durocher and Rickey look like the smartest men in the history of baseball. Whenever Basinski made a key play in the infield, announcer Red Barber would enthuse, “The violin is playing sweetly today!”

Basinski’s teammates ribbed him mercilessly about playing the violin, one reason that Basinski never brought his prized violin to the Dodgers’ Ebbets Field clubhouse. In fact, Durocher grew skeptical that he could actually play. So Basinski made Durocher a bet: He would play the violin in front of Leo and anybody else Leo wanted. If they like what they heard, Leo would pay Basinski $1,000. Durocher thought that over and accepted.

A few weeks later, Basinski showed up in the clubhouse and played selections from Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, and Victor Herbert. He also threw in a Strauss waltz. “Well, I’ll be a son of a bitch. The kid can play,” marveled Durocher. “A lot of people think musicians are pantywaists,” Basinski said. “That’s a bunch of nonsense.”8

Unfortunately for Basinski, he couldn’t sustain his hot hitting and finished the season at Double-A Montreal, where he hit .244. He played 108 games for the Dodgers in 1945, hitting .262 as the team’s most frequently used shortstop (star Pee Wee Reese was serving in the military). Although there was no All-Star Game that season due to the war, the Associated Press named two unofficial teams after polling managers, and selected Basinski and the Cardinals’ Marty Marion as the two NL shortstops.

With Reese back on board in 1946, Basinski spent the year with St. Paul of the American Association, where he hit .252 in full-time play. Then Basinski went to Pittsburgh in a December 5, 1946, trade for pitcher Al Gerheauser. After Basinski hit only .199 in 56 games for the 1947 Pirates, his major-league career came to an end and his PCL career began at age 24 when the New York Yankees, who had acquired him from the Pirates, sent him to the Portland Beavers.

“When I got out here (Pacific Northwest) I was floored by the beauty,” Basinski told The Oregonian. “And the people were just great. Buffalo neighborhoods were divided among ethnic groups, and gangs guarded their turf. Somebody who didn’t belong there was beaten up. Back there you’d introduce yourself and … they’d immediately categorize you. That didn’t happen in Portland. It finally dawned on me, and I said, ‘Hey, this is America!’”9

The Yankees wanted Basinski after the 1947 season, but he instead arranged to stay in Portland. “I knew there was an awful lot of politics up there,” he recalled. “When I turned the Yankees down, it was probably a terrible mistake. They won a lot of pennants after that. I would have been part of those great teams and made all that money. A lot of players who are just average players are highlighted because they won pennants.”10

In Portland, Basinski became a second baseman, and spent just over ten seasons with the Beavers, hitting between .240 and .278 while annually ranking among the top defensive players in the league. In 1950 Basinski played in every inning of the 202-game Pacific Coast League schedule. He played in 557 consecutive games at one point. “I would have broken Hugh Luby’s consecutive-game streak at second base – 886 games – had not Walt Dropo deliberately cut me down on a tag at second base. He was out by thirty feet – embarrassed, I guess – and he cut me down with a three-inch gash on my left shin.”11

In 1950 the Oregonian newspaper named him the club’s most valuable player. He became a fan favorite – in 1955, in a newspaper poll to name Portland’s all-time team, Basinski got more votes than anybody else. That probably figured, given that Basinski often trotted out his violin and performed home-plate recitals on Sundays between games of doubleheaders. “One time I got a tremendous ovation, and had a good doubleheader, too,” he said.12

Basinski figured that he would end his career with the Beavers. But on April 25, 1957, the Beavers waived the 34-year-old in a cost-cutting move, leaving him available for any team willing to pay the waiver price. The Rainiers acted swiftly, largely to add to their infield depth and also because of Basinski’s ability as a clutch hitter. When Basinski left Portland, he had played in 557 consecutive games and couldn’t understand his release. “I was shocked when Portland waivered me out,” Basinski told The Oregonian. “I’ll never understand why the club let me go. I had the second-best spring training of my life.”13

Basinski’s most notable series for the Rainiers came when they faced the Beavers for the first time in an early-season seven-game series. Basinski went 7-for-14, while missing four of the seven contests with an eye injury. After appearing in seven games for the Beavers, Basinski played in 129 games for the 1957 Rainiers, who went 87-80 under Lefty O’Doul, in his last year of managing. He hit .271 with a .712 OPS and often helped rookie Maury Wills with infield fundamentals. “I had more fun and enjoyed baseball more with Lefty O’Doul. I had admired him all the years playing against him [O’Doul had managed several PCL teams during Basinski’s career], and he was very complimentary to me. He used to say, ‘That god-damn Basinski. If it wasn’t for him, we would have won a lot more games.’ His hit-and-run sign for me was playing the violin left-handed in the third-base coach’s line.”14

Basinski posted a good year for Seattle in 1958 when he hit .301 with 47 RBIs (Basinski hit the first double of the season, winning 13 car washes from a Rainiers sponsor), but the Rainiers, despite 19-year-old sensation Vada Pinson hitting .343 in 124 games, flailed under manager Connie Ryan, finishing 68-86, at one point losing 14 consecutive games, just three shy of Sacramento’s 1925 league record of 17.

Despite Basinski’s numbers, the Rainiers figured that he didn’t have much left and sold him to Vancouver. In fact, he didn’t have much left. Basinski played in just 43 games and hit .138 for the 1959 Mounties. “He was unathletic looking,” recalled Mounties radio announcer Jim Robson, “but the kind of guy you want on your team. He undoubtedly helped the young infielders develop.”15 One of those infielders was Brooks Robinson.

During his PCL career, Basinski compiled 1,544 hits, 109 homers, and 634 RBIs, all while batting .260. He led the PCL in games played in 1950 and in at-bats in 1951.

After his career ended, Basinski settled in Oregon with his wife and two sons. He became an accounts manager for Consolidated Freightways in Portland, where he worked for 31 years, retiring in 1991. He took up bowling and golf in retirement. He had the honor of being inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame in 1987, the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame in 1996, and the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame in 2006. In 1984, he was named to the all-time PCL All-Star team. In 2014 the 91-year-old Basinski resided in Milwaukie, Oregon, a suburb of Portland.

“I don’t look like a big strong guy, but I was an iron man with Portland. My looks were always against my ability. I looked like a damn doctor or a preacher, and the glasses didn’t help. But man, I had the fire, and I wanted to be a perfectionist.”

“I settled in Portland, married there, had a couple of boys. I think that had a lot to do with turning down the Yankees. I’m sure it was a mistake as far as money, but I had the great love and devotion of Portland all those years.”16 Though he would occasionally be asked to play his violin for a baseball audience, he did so reluctantly. “I’m a perfectionist,” he admitted, “and if I can’t play well then I prefer not to do it.”17

This biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin. A version of this article, written by Dave Eskenazi with help from Steve Rudman, first appeared at sportspressnw.com on March 5, 2013. Mark Armour expanded Dave’s article for the book.

Notes

1 Craig Allen Cleve, Hardball on the Home Front: Major League Replacement Players of World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 119.

2 Cleve, Hardball on the Home Front, 119.

3 Eddie Basinski, interview with Chris Potter, youtube.com, 2011.

4 Cleve, Hardball on the Home Front, 120.

5 Cleve, Hardball on the Home Front, 120.

6 Eddie Basinski, interview with Chris Potter, youtube.com, 2011.

7 David Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine: Eddie Basinski, ‘The Fiddler,’ ” SportsPressNW.com, March 5, 2013.

8 Daniel J. Wakin, “Ballplayers Who Hit the Right Notes,” New York Times, June 24, 2011.

9 Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine.”

10 Larry Stone, “’Those were the most wonderful days I believe I ever had,’” in Mark Armour (ed.), Rain Check (SABR, 2006), 101.

11 Cleve, Hardball on the Home Front, 140.

12 Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine.”

13 Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine.”

14 Dobbins, The Grand Minor League—An Oral History of the Old Pacific Coast League (Emeryville, California: Woodford Press, 1999), 143.

15 Dick Dobbins, The Grand Minor League, 105.

16 Stone, “’Those were the most wonderful days I believe I ever had,’” 101.

17 Dobbins, The Grand Minor League, 154.

Full Name

Edwin Frank Basinski

Born

November 4, 1922 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.