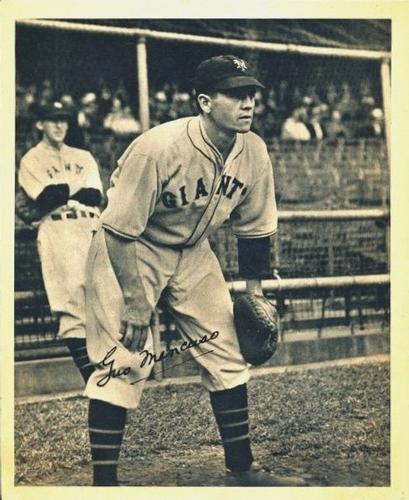

Gus Mancuso

Popular, smiling catcher Gus Mancuso played in five World Series and called signals for five Hall of Fame pitchers. In more than 40 years in baseball, he served as a minor league manager and major league pitching coach and broadcast games with Harry Caray.

Popular, smiling catcher Gus Mancuso played in five World Series and called signals for five Hall of Fame pitchers. In more than 40 years in baseball, he served as a minor league manager and major league pitching coach and broadcast games with Harry Caray.

August Rodney Mancuso was born in Galveston, Texas, on December 5, 1905. His grandfather, Stephano, had left Sicily with his wife and two sons, probably in the 1890s. Stephano died during the Atlantic crossing, but his sons Giacomo and Franco, Gus’ father, settled in Galveston. According to the family history, Franco was a dark-skinned man with some Moorish ancestry, like many Sicilians. Such immigrants were called “black dagoes” and were the targets of discrimination. (Gus was sometimes called “Blackie” during his baseball career.)

Franco dug oysters in Galveston and sold them to restaurants. He married Heppie Dana Lindermann, the daughter of a German immigrant father and a Cherokee mother. He moved his family to Houston, where he became head waiter at the White House Restaurant. Although he was a stern Old-World father, he adopted the American name “Frank” and insisted that his seven children speak only English because they were Americans. He demanded that they finish high school and work to go to college.

Frank Mancuso died in his forties and Heppie supported her large family as a midwife and nurse. Decades later “Granny” Mancuso would be a fixture at Houston Astros’ games, sometimes throwing out the first ball on Opening Day.

Gus, who was named after his German maternal grandfather, started playing America’s national game when he was about nine years old. If there were not enough boys to fill out two teams, they played one-eyed cat. As he remembered, “When nobody got you out, you continued hitting. If somebody got you out, you went out to left field and had to work your way back around to home plate.”

After he graduated from high school, Gus went to work at the Texas Company (later Texaco) for $40 a month, then moved up to $75 a month as a teller with the First National Bank. He was hired more for his baseball talent than his financial knowledge; he became a star of the bank’s baseball team and was spotted by Fred Ankenman, president of the Texas League Houston Buffaloes, in 1924.

Before Ankenman signed him, Gus played three games for Galveston’s Texas League club when their catcher got hurt. Years later he complained, “They still owe me for them.”

Houston offered him $125 a month and started him at Mount Pleasant in the Class D East Texas League, the bottom rung of professional baseball. The 20-year-old went to spring training with the parent St. Louis Cardinals in 1926 but returned to the minors. After the season he married Lorena Carolyn Sue Dill. They would have two children, Emma Jean and August Jr.

In 1927 Gus batted .372 for Syracuse in the International League, at the highest minor league level. That earned him his first serious big league trial. He made his major-league debut on April 30, 1928, and stayed with the Cardinals until July, when he was shipped to Minneapolis in the American Association. He spent 1929 with St. Louis’s American Association farm club at Rochester and with Houston.

The Cardinals had acquired one of the National League’s top defensive catchers, Jimmie Wilson, from Philadelphia in 1928, so the big league job was taken. In 1930 the club offered Mancuso an extra $1,000 if he would go back to Rochester. Mancuso agreed, saying he preferred to play every day in the minors rather than watch Wilson play in the majors. But the baseball commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, intervened to stage one of his rear-guard actions against the Cardinals’ growing farm system.

St. Louis general manager Branch Rickey had started a baseball revolution in the 1920s when he bought several minor league clubs and signed working agreements with others to create a pipeline for developing players. Landis realized that Rickey’s system would make minor league teams vassals of the majors and fought it at every turn. It was a losing battle; by 1940 the Cardinals controlled 32 teams and more than 600 players, and most other teams had followed their lead on a smaller scale.

Judge Landis also believed, accurately, that the farm system denied worthy players a chance at the majors. Since the Cardinals had already sent Mancuso down twice, the commissioner ruled that they must keep him or trade him. In his decision, he called Rickey’s system a “chain gang.” Gus said, “He got me started in the major leagues.”

As Wilson’s backup, Mancuso’s batting average climbed above .370 in limited duty. To keep in shape, he ran every day with the Cardinal pitchers. On August 9 Brooklyn led the National League, with the Cubs and Giants close behind. St. Louis was in fourth place, 12 games back. Starting that day, the Cardinals won four straight from Brooklyn and took off on a 38-9 sprint to the pennant.

On September 12 the Cardinals and Brooklyn Robins were just one-half game behind the Cubs. The Cards beat the Giants to push New York four games back, but Jimmie Wilson sprained his ankle and did not play again for the rest of the regular season. As St. Louis charged toward the pennant, Mancuso was a more than adequate replacement. He hit two home runs in one game against the Phillies (then caught the second game of that doubleheader) and contributed four hits in another win over Philadelphia. He finished with a .366 batting average and a .965 on-base-plus-slugging percentage. (Nineteen-thirty was the year of the hitter; the entire National League batted .303, and all of the Cardinals’ regulars and several bench players hit over .300.)

The Cardinals faced the Philadelphia Athletics in the World’s Series, as it was then called. Connie Mack’s Athletics were the same crew that had beaten the Cubs in the 1929 Series, led by Hall of Famers Lefty Grove, Mickey Cochrane, Jimmie Foxx and Al Simmons. They were the favorites to repeat.

Mancuso got the Cardinals’ first hit and scored the first run off Grove, but Philadelphia won the first two games. Mancuso had contributed two singles and a walk in eight plate appearances, but Wilson had recovered enough to replace him in the third game and catch the rest of the Series. Philadelphia won the championship in six games.

Although they were rivals for playing time, Mancuso said, “Jimmie Wilson was a great help to me.” In 1931 Gus again spent most of his time on the bench as the Cardinals won their second straight pennant. In the World’s Series rematch against the Athletics, he pinch-hit once and caught the final innings of a blowout sixth game as St. Louis turned the tables on Philadelphia and claimed the championship.

The next season Wilson turned 32 years old and shared the catching duties. Mancuso caught 82 games to Wilson’s 75 and batted .284, nearly 40 points higher than his mentor. At 26, Gus was in his prime and was eager for a chance to play regularly. He asked Cardinals owner Sam Breadon and general manager Rickey to trade him.

He got his wish. In 1932 a sick and bitter John McGraw had resigned after 30 years as manager of the New York Giants. His successor was first baseman Bill Terry, the National League’s last .400 hitter. When Terry took over in June, the Giants were in last place, and the players were near revolt against McGraw’s abuse. Terry could lift the club no higher than sixth place.

After the season Terry dumped more than half the roster he had inherited from McGraw. Mancuso was his first acquisition. He traded two of his starting pitchers, Bill Walker and Jim Mooney, plus catcher Bob O’Farrell and outfielder Ethan Allen for Mancuso and minor league pitcher Ray Starr. Then Terry sold the Giants’ first-string catcher, the huge and popular Shanty Hogan. “Mancuso is the best catcher in the National League today,” the manager declared.

When Terry said “the best,” he was referring to defense. Future Hall of Famers Ernie Lombardi and Gabby Hartnett were more powerful hitters, but that didn’t matter to the Giants’ manager. Following McGraw’s philosophy, Terry built his team around pitching and defense. Paul Richards, the Giants’ backup catcher in 1933 and a long-time manager, said, “He concentrated almost entirely on defense. His theory was not to let the other club score and they’d beat themselves. Naturally, most ball games are lost rather than won.”

Mancuso recalled Terry’s marching orders: “Gus, you’re the catcher and you’re going to handle these pitchers. I’d like for you to just take ’em over.”

At the top of the list of “these pitchers” was Carl Hubbell. The left-hander had already established himself as one of the National League’s best, but he had never led the league in ERA and had never won 20 games in a season, then the benchmark for pitching success. In 1933 Hubbell turned into the best pitcher in the majors. He won at least 21 games for the next six years and led in ERA three times. His 1933 ERA, 1.66, was the lowest since 1919, when Babe Ruth began hitting home runs in large numbers. Mancuso said the two of them worked for hours during spring training until Hubbell learned to keep his trademark screwball away from lefthanded batters. The screwball broke in on lefthanders and could end up in their power zone if Hubbell put it on the inner half of the plate.

Terry promoted two young right-handers into the starting rotation. Twenty-two-year-old Hal Schumacher won 19 games with a 2.16 ERA. Twenty-six-year-old Roy Parmelee, who had been trying to make the team for four years, contributed 13 victories and a 3.17 ERA. The senior member of the rotation, Freddie Fitzsimmons, added 16 wins and a 2.90 ERA

Terry evidently understood that each of his front-line pitchers needed a sure-handed, agile catcher, something the 240-pound Shanty Hogan definitely was not. Hubbell’s sharp-breaking screwball and Schumacher’s diving sinker were a challenge for any backstop. Fitzsimmons threw a knuckleball, a catcher’s worst enemy. “Parmelee had as much stuff as any four or five pitchers put together,” Mancuso said, “but he didn’t know where it was going.” In 1933 he led the league in hit batters and wild pitches.

The rebuilt Giants won their first pennant in nine years while allowing the fewest runs in the league. John Drebinger, who covered the team for The New York Times, said they overcame an “inferior attack” with “brilliant pitching and a firm air-tight defense.”

In the first game of the World Series against Washington, Hubbell cruised to a 4-2 victory. Gus noticed the Senators’ hitters moving to the front of the batter’s box to try to hit the screwball before it broke: “Carl just showed them the screwball once in a while that day. While they were looking for it he fanned [10] with fastballs.” Mancuso threw out a runner trying to steal to kill a potential rally.

In game two the Giants scored six times in the sixth inning to beat the Senators 6-1. During the winning rally the lead-footed Mancuso stunned practically everybody in the ballpark when he beat out a squeeze bunt that brought home a run. More than 40 years later, he chuckled, “I couldn’t run any faster then than I can now.” (Drebinger once wrote that he “always looks to be running in a sand pile.”)

The Giants won the Series in five games. The veteran reliever Dolf Luque struck out Washington’s Joe Kuhel to end it. An Associated Press writer reported, “When that last ball thudded into Gus Mancuso’s mitt the Giant catcher leaped far off the ground waving both arms in the air and letting out a victory whoop that could be heard above the noise of the crowd. Then he ran to throw his arms around Luque, holding out the victory ball to him when the pitcher asked for it.”

In an Associated Press poll of 89 sportswriters and editors, Mancuso finished second to the Yankees’ Bill Dickey as the majors’ all-star catcher “on the strength of his ability to handle pitchers so skillfully.” The New York World-Telegram‘s Dan Daniel judged him to be the “real spark-plug of the Giants Peppery, smiling, hard worker, timely batsman.”

“The catcher’s got to have the pitcher’s confidence,” Gus said. “The main thing that I found was, rather than studying the hitters so hard, was to study your pitchers, their strengths.”

Starting in 1933, the Giants won three pennants in five years, finishing second and third in the other seasons, with at least 91 victories each year. They lost the 1936 and ’37 World Series to Joe McCarthy’s Yankee dynasty. Mancuso was the Giants’ regular catcher, reaching career highs in 1935 with nine home runs and 63 RBI. He was selected for the 1935 and 1937 All-Star teams.

A few days after the ’37 All-Star Game, a foul tip broke the ring finger on Mancuso’s right hand. Harry Danning, who was five years younger, had been backing up Gus for three seasons and waiting impatiently for his chance. He took advantage of it, hitting well and showing more power than Mancuso. When Gus returned in September, the two shared the job for the rest of the season. Gus started the first two World Series games against the Yankees, but after he went hitless Danning took over.

After the season, Mancuso was rumored to be on the trading block, but he returned to the Giants in 1938 as the second-string catcher. In the fall he was reported to be a candidate for managers’ jobs in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. Instead, Terry traded him to the defending NL champion Cubs. It was a straight-up swap: catcher Mancuso, shortstop Dick Bartell and outfielder Hank Leiber to Chicago for catcher Ken O’Dea, shortstop Bill Jurges and outfielder Frank Demaree.

The Cubs’ catcher and manager, Gabby Hartnett, was 38 years old and split the duties with the 33-year-old Mancuso. Before spring training Chicago Tribune writer Ed Burns said the club’s catchers would be “the best in the league,” but after watching their performance throughout the season Burns called them “two creaky veterans.” Mancuso’s on-base-plus-slugging percentage was a weak .593.

In 1939 Gus’ brother Frank tried out with the Giants as a catcher, but never got into a game. (He returned to the majors later.) Another brother, Leon, caught in the minors before Gus helped him secure a Texaco gas-station franchise. Gus had supported several family members during the Depression years of the ’30s. His highest salary was $14,000, supplemented by $500 when Terry named him captain of the Giants, a small fortune when as many as one-fourth of American workers were unemployed. Family members said his one vice was gambling; he sometimes lost as much as $1,000 in a night at the poker table.

Mancuso spent six more years as an itinerant second-string catcher, prolonging his career during World War II when most major leaguers went into military service. When he was traded to Brooklyn in December 1939, Dodger manager Leo Durocher said, “He has a way with pitchers.”

Branch Rickey brought Mancuso back to the Cardinals in 1941 to steady their young pitchers and to help school their rookie catcher, Walker Cooper. When Cooper missed two months with a broken shoulder, Gus caught 105 games but batted only .229.

Gus returned to the Giants, now managed by his former teammate Mel Ott, in 1942 as a backup catcher and pitching coach. When the Army called Harry Danning the next year, Mancuso became the club’s first-string catcher at age 37, sharing the job with 35-year-old Ernie Lombardi.

During that season Mancuso talked about pitchers with Joe King of the New York World-Telegram. He said control, not great stuff, is the foundation of pitching success. He had caught future Hall of Famers Grover Cleveland Alexander, Dizzy Dean, Burleigh Grimes, Jess Haines and Hubbell, as well as many of the National League’s other top pitchers. “Greatness is something extra, something personal and it cannot be tracked down,” he said. “I would call it courage. The greatest feat I ever saw, and caught, was Hal Schumacher’s fanning of Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey and Lou Gehrig with three on bases in that ten-inning game he won in the ’36 World’s Series.” (It was the third inning of game five, but Mancuso’s memory, or King’s reporting, was faulty: DiMaggio and Gehrig struck out with the bases loaded, and Dickey flied out.)

He said the greatest game he caught was Freddie Fitzsimmons’ “masterpiece” in that same ’36 series. In the third game Fitzsimmons held the powerful Yankees to four hits, but lost 2-1 when Frank Crosetti’s grounder caromed off the pitcher’s glove to drive in the winning run.

Hubbell, of course, was his choice as the best pitcher he ever saw ”by far.” The Giants’ “Meal Ticket” had won 24 straight games in 1936 and 1937, most of them with Mancuso behind the plate; he pitched a National League record 45 consecutive scoreless innings in 1933, when Mancuso was his catcher; and he won an 18-inning shutout against the Cardinals on July 2, 1933, with Mancuso calling the signals. If that wasn’t Gus’ most memorable game, it may have been because he was too tired to remember it. He also caught the second game of that day’s doubleheader, when Parmelee pitched another shutout. After catching 27 scoreless innings – the two games lasted 5 ½ hour – she took Lorena to a Broadway show in the evening. He said his legs cramped while he was sitting and he waddled out of the theater bent over like an old man.

He and Lombardi again shared the Giants’ catching duties in 1944. On September 1, a Dodger pitcher hit New York’s Joe Medwick. Under a common, but unofficial, practice at the time, Medwick was permitted to leave the game temporarily for medical treatment, and the opposing manager, Leo Durocher, chose a “courtesy runner” to replace the injured batter. Doing the Giants no favors, Durocher put the slow-running Mancuso on first base. The next batter was Lombardi, possibly the only man in baseball slower than Gus. The result was a lock: Lombardi grounded into a double play.

After the season the Giants released Mancuso as he approached his 39th birthday. In a tribute usually reserved for retiring superstars or the recently deceased, a Sporting News editorial saluted him as “the National League’s most skilled receiver of his time, and one of the most underrated backstops in two decades of major league competition. No matter where Gus goes, he will carry with him the best wishes of all followers of the game.”

The baseball obituary was premature. Former teammate Freddie Fitzsimmons was managing the National League’s perennial doormats, the Philadelphia Phillies, and persuaded Gus to come aboard as a part-time catcher and full-time pitching coach in 1945. After Fitzsimmons was fired, Mancuso left the club before the end of the season.

Although Mancuso was not a big star, the Wilson Sporting Goods Company capitalized on his defensive reputation in advertisements during the 1940s and ’50s featuring the “GM-Gus Mancuso” model A2420 catcher’s mitt, “the last word in receivers’ mitts.”

In the fall of 1945 The Sporting News reported that Mancuso had his pick of several minor league managing jobs. He chose Tulsa, the Texas League affiliate of the Cubs. He said, “I feel just like a kid with a new toy, and I’m thrilled to start my managerial career in Tulsa.” The club finished fourth with an 84-69 record.

He returned to Tulsa in 1947 and moved to San Antonio, the Texas League farm club of the St. Louis Browns, in 1948 and 1949. In 1950 Cincinnati manager Luke Sewell hired him as pitching coach. Sewell had managed the Browns to the only pennant in their history in 1944, with Gus’ brother Frank as one of his catchers.

In 1951 Gus began a new career as a broadcaster with his hometown Houston team in the Texas League. In mid-season the sponsor, Griesedieck Bros. Brewing Corporation, moved him to St. Louis, where he joined play-by-play announcer Harry Caray on the Cardinals’ growing radio network. By 1953 more than 80 stations beamed Cardinal games to the Midwest and South over the largest network in baseball.

Anheuser-Busch bought the team that year and the company’s Budweiser beer began sponsoring Cardinal broadcasts in 1954. Busch kept Caray, despite his long association with the rival beer, but dropped Mancuso in favor of newcomers Jack Buck and Milo Hamilton. Mancuso scouted for the Cardinals and returned to the radio booth in the late 1950s with Houston and San Antonio in the Texas League.

In 1960 Gus was out of baseball for the first time in 36 years, but not for long. He joined Houston’s National League expansion team as a part-time scout before the team began play in 1962. He wrote a column for the Houston Press and Griesedieck Bros. put him back on the air on pre-game and post-game shows surrounding the new Colt .45s broadcasts. (Griesedieck Bros. had merged with the Falstaff Brewing Company, which was owned by another branch of the Griesedieck family.)

In October 1962 Gus’ wife Lorena was killed in a car wreck in Houston. Gus suffered minor injuries. Several years later he married Estelle Deshazo Schumaker, a widow who converted to his Catholic faith.

In retirement he worked part-time as a sales representative for a moving company in Houston. He regretted that he had not saved any money during his baseball career and counseled his grandson and namesake to take business courses in college. Colonel August Mancuso III recalled, “He was always big on treating folks decently, and he could be absolutely relied upon to keep a confidence. He always wore a great big smile. I don’t believe I ever saw him angry, but when he got real quiet and the smile left, you shut up and started wondering what you did wrong.”

Gus contracted emphysema (he had smoked cigarettes until the 1960s) and in 1982 he delivered much of his baseball memorabilia to his grandson. He died on October 26, 1984, just short of his 79th birthday. Estelle and his daughter Emma Jean survived; his son August Jr. had died in 1981. He is buried in Forest Park-Lawndale Cemetery in Houston.

Sources

Most information about Mancuso’s baseball career comes from The Sporting News and The New York Times.

Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis. HarperCollins, 2000.

Donald Honig, “Paul Richards,” in The Man in the Dugout. Follett Publishing Company, 1977.

Colonel August R. Mancuso III (U.S. Army, Ret.), the player’s grandson, provided information about his family and personal reminiscences.

Texas Gulf Coast Historical Association, oral history interview (undated, probably 1980), conducted by Houston sportswriter Clark Nealon and provided by Colonel Mancuso.

Peter Williams, When The Giants Were Giants. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994.

www.gb-beer.com.

Full Name

August Rodney Mancuso

Born

December 5, 1905 at Galveston, TX (USA)

Died

October 26, 1984 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.