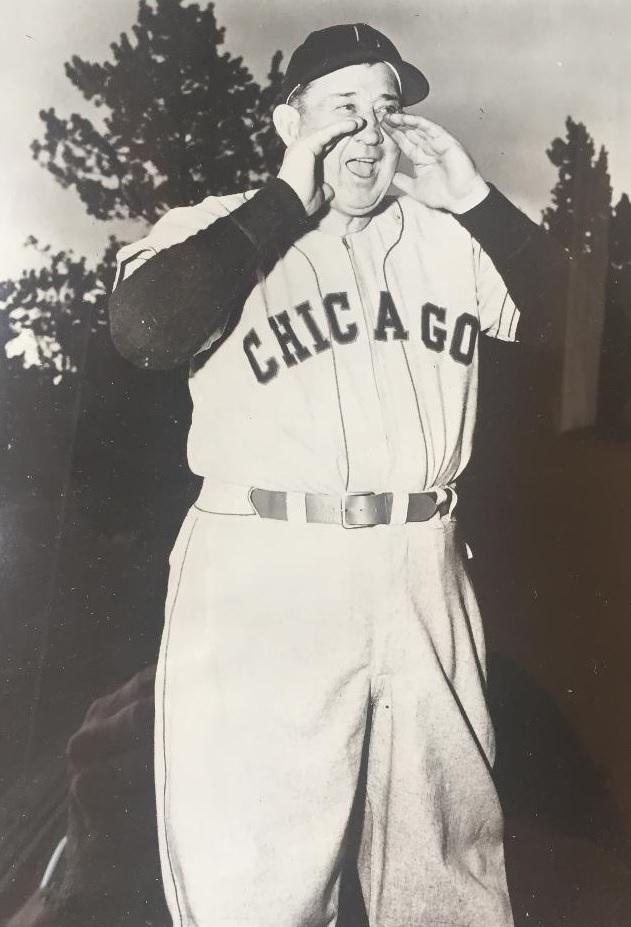

Jack Onslow

Over a 50-year career in baseball, a man is likely to pick up a few nicknames, and for Jack Onslow this was no exception. He liked to call himself “The Travelling Man,” and the logic to that will become obvious. He also was referred to as “Happy Jack” and “Honest John,” names that could have both positive and negative connotations. Onslow began his career as a minor-league catcher in 1909 when he learned “you could actually get paid to play baseball.”1 He was still a scout for the Boston Red Sox at his death in 1960, wearing many hats in many places over the years.

Over a 50-year career in baseball, a man is likely to pick up a few nicknames, and for Jack Onslow this was no exception. He liked to call himself “The Travelling Man,” and the logic to that will become obvious. He also was referred to as “Happy Jack” and “Honest John,” names that could have both positive and negative connotations. Onslow began his career as a minor-league catcher in 1909 when he learned “you could actually get paid to play baseball.”1 He was still a scout for the Boston Red Sox at his death in 1960, wearing many hats in many places over the years.

Onslow was a weak-hitting catcher but possessed good baseball instincts that he parlayed into positions as manager, coach, instructor, radio show host, announcer, public relations director, celebrity speaker, scout, and minor-league director. He was involved with over 20 teams at many different levels of professional baseball, often moving from one to another in quick succession. And during both World War eras, when he was out of Organized Baseball, he managed and played for three successful company-sponsored industrial teams.

Jack’s “happy” and “honest” temperaments could both make him both a desirable hire and a man who would wear out his welcome. “Happy” Jack was a gifted, humorous story-teller who could hold an audience for hours or use an example with a young player to make a point. At the same time, he was thin-skinned, easy to antagonize when opponents found a weak spot in his persona, unable to handle criticism or perceived disrespect with aplomb. A stickler for discipline and hustle, he had a knack for achieving success wherever he went, but often at a price of clubhouse tension and exhaustion.

John James Onslow was born at Scottdale, Pennsylvania, about fifty miles east of Pittsburgh on October 13, 1888. He was the second of four children of James and Ellen Onslow. James, who made a living as a manager for the Home Oil Company, competed in long-distance running. Eddie Onslow, Jack’s younger brother by four years, would have a long baseball career like Jack. Athletics was a significant part of Onslow family life: “My father was a baseball bug, and the first thing I remember is throwing a baseball at my brother, Ed.”2

The family moved to eastern Ohio when Jack was nine years old. Onslow played baseball and football at Mount Pleasant, Ohio, High School, then continued in both sports at nearby Scio College.3 He was playing semipro baseball in nearby Pennsylvania when, in 1909, Burt Sapp signed him to a contract with the Dallas Giants in the Class B Texas League. Onslow had a sub-.200 batting average at Dallas in 1909; nonetheless, he became the regular catcher for the Giants in 1910, hitting a weak .192. A solid five-foot-ten, 180-pound right-hander, Onslow’s contract was purchased by Detroit Tigers owner Frank Navin during the season. Navin opted for Onslow instead of another young catcher, Ray Schalk, because Schalk appeared too small.4

Detroit kept Onslow in the minor leagues for 1911, assigning him to catch for Fort Wayne (Indiana) of the Class-B Central League. His batting average rose to .242 for the Brakies who finished second in the league; he showed enough skill for the Tigers to bring him up to the parent team for 1912.

Onslow opened the season on the Detroit bench, backing up catcher Oscar Stanage. Stanage was a 29-year-old workhorse whom Tigers owner Navin greatly admired. He had a better bat and arm than Onslow, who could not outperform him — but could hope to back him up. Onslow made his major-league debut on May 2, 1912, going hitless in three plate appearances in Detroit against the St. Louis Browns. The next day, he came to the plate five times, hitting two singles, walking twice, and driving in two runs; the Tigers won the game, 16-5, over the Browns.5 But Onslow did not get along well with manager Hughie Jennings. Although the other backup catcher, Brad Kocher, did not have fielding skills equal to Onslow’s, he took playing time away from Onslow, who often idled in Jennings’ doghouse for weeks at a time during the season.

On December 19, 1912, Onslow’s contract was sold to the Providence Grays of the International League along with his younger brother, Eddie’s6 — and Kocher’s. The Grays were on the rise under manager Wild Bill Donovan, and both the Onslow brothers would benefit from their years with the team — in their own ways. Eddie’s bat caught fire in 1914, his batting average rising to .322, the first of 14 .300-plus seasons in the International League. Jack couldn’t match that, but he could learn from Donovan, who had over 180 major-league wins as a pitcher. Onslow practiced his pitcher-management skills with young Babe Ruth as a batterymate, catching nine of the Babe’s 12 pitching appearances for the 1914 Grays.7 Ed Onslow would remain one of the International League’s top first basemen through 1928, the league’s most durable presence, whereas Jack would move — and move some more.

Jack Onslow was married for the first time in 1913. Audrey Mercer and Onslow were together for 18 years. Audrey’s refusal to travel may not have been an ideal match for “The Travelling Man;” they divorced in 1931. Onslow’s second wife, Vivian “Vee” Skrupa, was from Syracuse, New York; that marriage took place in 1943, and also lasted 18 years, until Onslow’s death. Vee went where Jack went.

Jack remained a Gray for two years, sharing the catching load with Kocher before he was waived to Buffalo in 1915. There he caught for the Bisons for two years; his 1916 season was a relative success for him at the plate as he hit .279 in 351 at-bats — and even bashed three home runs. Along with his skills, Onslow helped bring pennants to Buffalo; the Bisons won the league in his two seasons there, as his résumé developed

Onslow’s batting average with Buffalo was back in the doldrums in 1917. Nonetheless, in August, his contract was bought by the New York Giants. The Giants were well-staffed in backstops with Bill Rariden, Lew McCarty, and George Gibson, so the weak-hitting Onslow was strictly a safety measure for manager John McGraw. The Giants were on their way to a National League pennant and a World Series loss to the Chicago White Sox. Rariden saw most of the Series action, McCarty the rest. Onslow sat on the bench, and somewhat charitably was awarded a full Series share.8 McGraw had not given his 29-year-old fourth catcher much of a chance, but he appears to have given Onslow a blueprint for managing style. McGraw was thumbed from 118 games during his career, often tongue-lashed players, and fought with umpires,9 but had a great respect for the game, and the need to play it as such. Called up on August 25, with the Giants having 39 games to play and a comfortable lead, Onslow made only two starts and came up to bat only nine times — but he watched and absorbed.

In the final game of the regular season, Onslow replaced Gibson at catcher. He came to the plate twice, got a double and a single, and scored a run in a 6-0 win over the Philadelphia Phillies. It was his last major-league game as a player — but a good one to remember.

The Giants had a working arrangement with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association to take on some of their surplus players; in April 1918, the Giants sent Onslow along with six other players to Kansas City. The American Association season was truncated due to World War I, but Onslow played in most of the Blues’ games, hitting .263. After the season was shut down on July 21, Onslow landed a job manufacturing munitions for Allegheny Steel in Pittsburgh, and quickly became the catcher for the company’s industrial-league team. Onslow’s brother, Eddie, soon joined him and became the team’s first baseman. Jack adjusted well to industrial-league pitching — batting a startling .392 for his team, the Tarentum Steelers.

In January of 1919, Allegheny Steel announced that Jack Onslow would be the player-manager for the team. He would remain the Steelers manager for three seasons — an eon in Onslow-years. Perhaps it was the macho environment of blast furnaces and slag heaps, but Onslow’s rough-and-tumble personality really emerged in Tarentum. He was likely to spit in the face of an umpire during a game, then seek him out for fisticuffs behind the stands afterwards. Visiting lady fans were mortified by his salty language on the field. However, since the Steelers won three pennants in a row, the Allegheny management overlooked Onslow’s on-field demeanor.10

But Onslow’s days of Allegheny bliss could not go on forever. When the war ended late in 1918, the steel industry lost much of its military business; the necessity of fielding a baseball team began to lose its allure in the company budget. When the 1921 Steelers’ season barely received the financial go-ahead from the company, the writing was on the wall. So, in 1922, Onslow moved on, this time to manage and catch for the Mahanoy City Blue Birds, an independent team sponsored by a small industrial town in the coal fields of northeast Pennsylvania. His managing success continued as his team won the Anthracite League championship.11

Onslow, who would seem to have appeared nationwide by the time his career ended, made his one West Coast stop in 1923 when he became the catcher for the Portland Beavers of the Class AA Pacific Coast League. Having been considered to have “jumped” his Kansas City contract, he needed to seek and receive reinstatement from Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis. Onslow’s presence didn’t hurt, as the usually mediocre Beavers rose to third place in the PCL with a 107-89 record; he hit .266 in 252 at bats. But in 1924, he was back east, this time as player-manager for the Class B Richmond Colts (Virginia League). Now age 36, he gave himself 418 at-bats and hit .246. The Colts won the league title under Onslow with a 76-59 record. But Onslow was let go as the Colts were sold, and the new owners wanted their own man.

Onslow signed as the pitching coach for manager Bill McKechnie’s Pittsburgh Pirates on December 2, 1924. In a position of authority, Onslow was confrontational, micromanaging the performance of players, whereas McKechnie was quiet and mild, treating his players as men who could decide for themselves what was best. The two men were opposites, but with a strong affinity for one another. McKechnie would have Onslow on three of his major-league staffs. The 1925 Pirates were a mixed bag; though talented, they were limping along, barely over .500 in early June. Then Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss decided that Fred Clarke, Pittsburgh’s great manager from earlier in the century, should second-guess McKechnie on the Pirate bench. The strategy appeared to work when the Pirates rose up to win the World Series in 1925, and happiness should have abounded for Onslow and his new team. It was even pointed out by the Pittsburgh writers that championships were won wherever Onslow went — and here he was!12

But Dreyfuss was fickle in his success. He fired McKechnie and brought in Donie Bush to manage the Pirates.13 Onslow soon asked for, and received, his release.

Onslow did not remain unemployed for long. In late November, the Washington Senators announced that he would join Bucky Harris’s staff as the pitching coach for the 1927 season.14 The press noticed that Onslow had no experience as a pitcher, but that his teams usually were champions.15 The Onslow pennant magic didn’t take hold in Washington as the Senators finished third with an 85-69 record. August was a busy month as brother Eddie came to play a few games for the Senators, closing out his spotty major-league career. At about the time Eddie arrived, Jack put a damper on the reunion by getting “indefinitely suspended” by American League president Ban Johnson for involvement in a fracas with umpire Clarence Rowland; the brothers may have missed once more being on a major-league field together.16

Onslow was released from his Washington contract in December, but the new St. Louis Cardinals’ manager, McKechnie, quickly signed his old friend as a coach. McKechnie, with Onslow’s help, led the Cardinals to the 1928 pennant, only to be swept by the New York Yankees in the World Series. Onslow made the papers during the Series for letting the Yankees’ Leo Durocher get under his skin. After one game, Onslow took a swing at Durocher in the stadium tunnel, a punch that was detoured when Babe Ruth’s massive paw got in its way.17

McKechnie had once again opted to work for hard-to-please club owners; he was fired and replaced with Billy Southworth. Onslow also made his exit, another pennant on his résumé, to coach for the Newark Bears where his brother, Eddie, still an active player, was a first baseman. The Onslow magic didn’t transfer this time as the Bears, managed by Tris Speaker, finished in the second division of the International League during Jack’s two-year stay.

Onslow was back in the National League in 1931, acting as pitching coach for manager Burt Shotton’s Philadelphia Phillies, where he lasted for two seasons before being dismissed. From there, he went back to Richmond as manager for the 1933 season, sending himself to the plate 23 times for a .304 average; at age 44, it was his final year as a player. The Boston Red Sox then took him on as a coach for 1934. His employment with the club lasted only a year, but Onslow decided to make the Boston area his permanent home.

The Sporting News had a terse but accurate summary of Onslow’s talents up to this point in his career: he was an excellent teacher but a hard driver; also considered a poor loser.18 But now in Boston, “Happy Jack” emerged.

In 1935, Onslow began a new career — in radio. He was hired by the Boston Bees19 as an on-air baseball instructor, starring in the show “Baseball School of the Air.” Onslow began his broadcasting career for the Yankee and Colonial networks in Boston, doing 15-minute shows before the dinner hour. His nerves jangling in front of a microphone for the first time, Onslow blurted out his first words: “Good afternoon, Jack Onslow, this is everybody speaking.”20 Aside from his radio show, Onslow acted as a scout for the Bees, combing the greater Boston semipro leagues; his signees included longtime Braves infielder Sibby Sisti. He also acted in a public relations capacity for the club, speaking at local banquets, telling the audience tales from his years in the game.

In August of 1936 Onslow conducted a try-out camp for 600 youngsters at the Bees ball park while the team was out of town but found no strong prospects. The try-out attendance increased to 1,253 the following year, and several prospects were uncovered. Bill McKechnie was the Bees manager at the time, and brought his old buddy, Onslow, onto the field to coach. These years may have been Onslow’s happiest in baseball. The Bees had him working in so many varied capacities that he had little time to get into arguments, develop grudges or make his demanding personality onerous.

But in 1938, Onslow’s world began to change. McKechnie went on to Cincinnati to become the Reds manager and was replaced in Boston by Casey Stengel. Stengel’s personality clashed with Onslow’s. So, in January 1940, Onslow was assigned by the Bees as manager of the Hartford Laurels in the Eastern League, losing his radio job and other duties in Boston. His stay at Hartford was a roller coaster. In the 1940 season, he led the Laurels to an unexpectedly successful 72-66 season, and the league playoffs. But the hard-earned enthusiasm went down the drain the following year as the team sunk into last place with a 13-game losing streak.21 Onslow resigned, then went back to scouting around Boston and banquet appearances once again.22

When World War II dried up the opportunity for scouting in 1943, Onslow returned to the wartime baseball he understood so well, managing an industrial team for the Lowell Ordnance Company; he would be out of professional baseball for over three years. He moved to West Acton, Massachusetts, his home for the rest of his life, and married the former Vivian “Vee” Skrupa. In the mid-1940s, he spent time as a volunteer sports writer for the Acton Beacon, and as an assistant baseball coach for Acton High School. He and Vee never had children of their own, but raised the orphaned children of Vee’s sister, Bill and Mary Jane Collins. Young Bill spent his summers as batboy for Jack’s various teams.23

Onslow signed as a scout for the Chicago White Sox in January 1947; he also worked as a coach for White Sox players during spring training. In June, the White Sox appointed Onslow as manager of their farm team in Waterloo, Iowa, the Whitehawks of the Three-I League. Replacing Johnnie Mostel, Onslow led the Whitehawks to fourth place and a playoff berth; the team improved its record by 24 games under Onslow’s leadership.

The White Sox were happy with Onslow’s result, and re-signed him to manage the Whitehawks, but then, when Memphis Chicks’ manager Doc Protho resigned in January, 1948, the White Sox moved Onslow up. The Chicks had gone 69-85 in 1947, but Onslow would — almost — pull off another pennant-winning miracle in 1948. Memphis was 92-61, finishing second, three games behind Nashville.

Onslow was about to turn 60, but the White Sox seemed to think they had a wunderkind. Legendary White Sox pitcher Ted Lyons had lost 101 games in 1948 as manager; he resigned — and there was Onslow with his success in Memphis. Chuck Comiskey, the 22-year-old heir to the Sox franchise, was dazzled by the numbers, and insisted on Onslow’s promotion, ignoring the wishes of newly-hired general manager Frank Lane, who wanted Paul Richards, current skipper of the Detroit Tigers’ Buffalo affiliate, to be the manager.

Onslow was not charitable about how Lyons had managed or how the players had performed: “Some of Lyons’s players got $17,500 and they didn’t give him $17.50 worth of baseball. But that part of shortchanging is over. I’ll not be satisfied with less than 100 cents of value for every dollar on the payroll.”24 Sox players were notified not to bring their wives nor their automobiles to 1949 spring training. When they arrived at camp, they were given personalized schedules for each day telling them where to be, what to do. Onslow was out to keep his promise.

Onslow’s first season as a major-league manager had some positive results. The White Sox’ record improved by 12 wins in 1949, and they moved up to sixth place. Attendance improved by 150,000, a trend dear to the Comiskeys. And Lane was becoming an active and successful general manager, bringing about personnel changes that would be the basis for 17 consecutive winning seasons. By the start of the 1950 season, “Trader” Lane, as he was known around baseball, had worked close to 30 deals, bringing in talent such as Nellie Fox, Billy Pierce, and Chico Carrasquel.

But these stars-to-be were still young, not quite ready to lead the franchise out of the wilderness. Onslow’s 1949 club was playing .500 ball towards the end of May when rookie star Gus Zernial broke his collarbone diving for a line drive. The Sox went into a tailspin, could not recover, and finished sixth. Onslow’s impatient and demanding style, punctuated in the clubhouse by loud arguments — with catcher Joe Tipton, infielder Cass Michaels, and Lane — distracted the players and began to alienate the Comiskeys. Onslow berated Lane: “You’ve been second-guessing me all season” while describing him to the press as a “front-office ink-thrower.”25 The good will attained from his Waterloo and Memphis successes was totally eroded.

Each Onslow fracas got plenty of attention from the press over the last two months of the 1949 season and the following winter, leading to speculation about firing, complicated by Onslow’s two-year contract. Chuck Comiskey had turned against Onslow, but Comiskey’s mother and sister prevailed to retain him for 1950.

Onslow’s tenure as manager ended the following season, on May 26, 1950, after a 2-1 home loss to Bob Feller and the Cleveland Indians. The Sox were 8-22, in last place and 14½ games out of first. Red Corriden, 62 years old, was named as interim manager26 for the rest of the season. Corriden had a 52-72 log and led the White Sox back to another sixth-place finish.

After the White Sox, Onslow continued to have job opportunities. In the autumn of 1950, he was signed to manage the Milwaukee Brewers, a Red Sox farm team, then reconsidered to sign as manager of the youthful Chattanooga Lookouts, the Washington Senators’ Southern Association affiliate for 1951. In January of 1952, Red Sox manager Lou Boudreau signed Onslow and Onslow’s old hunting partner-boss, Bill McKechnie — Onslow as a scout, and McKechnie as pitching coach. Onslow retained the position for the rest of his life, scouting the New England area, filling demands for his speaking appearances at local banquets, fishing with other baseball old-timers (Ted Williams, Red Rolfe27), and hunting with his three prize bird dogs, Buck, Joe Argyle, and Lady.

Jack Onslow died of a heart attack on December 22, 1960, hours after plowing snow at his home in West Acton. He was buried at the family burial plot in Scio, Ohio. Vivian Onslow survived her husband by 45 years, dying at age 100 in 2005.

Sources and Acknowledgements

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I also used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for player, teams, box score, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this biography. I obtained information from The Sporting News through PaperofRecord.com and from the Newspaper Archives.com websites. I am indebted to Penny Purviance of Columbus, Ohio, Onslow’s grand-niece who gave me her time and assistance on phone calls, e-mails, and copies of photos. Nancy Purviance, Onslow’s 98-year-old niece (Penny’s mother, and daughter of Eddie Onslow) was invaluable with her memories, related to me through her daughter. Also, I am indebted to the Harrison County (Ohio) Genealogical Society for providing information and news clippings from their archives.

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 John Drohan, “Onslow, with Old Score to Settle, Vows to give Stengel the Works,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1949: 11.

2 Buffalo Commercial, July 12, 1917: 11.

3 Scio College was absorbed into Mount Union College (Alliance Ohio) in 1911. Lostcolleges.com

4 “Passed Up as a ‘Runt’ Young Schalk Developed into a Great Backstop,” Palmyra Spectator, July 9, 1919: 4

5 In his limited (45 game) career, this was, arguably, Onslow’s most successful day at the plate.

6 Ed Onslow, five years younger than Jack, began his professional career with Lansing of the Michigan League in 1911. A first baseman, he had hit .311 in 1911, and was banging up the league at .385 when the Tigers called him up in August. The Tigers’ regular first baseman, Del Gainer was injured, and they needed a backup.

7 On September 5, 1914, Onslow was the catcher when Babe Ruth shut out the Toronto Maple Leafs on one hit and cracked his first professional home run. Onslow went three for five with a double, batting eighth. Arthur O. Schott, Baseball Research Journal, vol. 1, “The Babe’s First Big Box Score,” 1972.

8 McGraw didn’t need to include Onslow, but he did — a gesture of respect from the crusty manager. See “McGraw Decides to enter Jack Onslow in the Big Series,” Buffalo Courier, September 22, 1917: 10.

9 Don Jensen, “John McGraw,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org accessed.

10 Onslow could be a bull in a china shop. One day in Pittsburgh, he decided to buy a new catcher’s mitt. He picked out a glove, and began pounding the pocket to break it in. The clerk took the glove from Onslow and put it on the glass counter to wrap it. Onslow couldn’t resist giving the glove one more good whack, shattering the whole counter, and considerably adding to the cost of his purchase. Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 4, 1925: 11.

11 Onslow’s on-field demeanor didn’t skip a beat. The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported “Onslow recently got into a jam with Bill Haigh, the Tamaqua pilot, and smeared him with a parting shot on the chin, this developing into a small-sized riot, with Onslow escorted from the field under police protection.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 23, 1922: 20.

12 “Flags Follow Jack Onslow and He’s on Pirates’ Side,” The Pittsburgh Press, October 6, 1925: 13.

13 McKechnie moved on to the St. Louis Cardinals as a coach, then manager.

14 “Onslow Lands Senator Berth,” The Pittsburgh Press, November 24, 1926: 17.

15 “Jack Onslow, Senator Pitcher Coach, Never Has Worked on the Slab,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 3, 1927: 31.

16 “Onslow Goat of Big Fuss,” Mt. Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, August 19, 1927: 8.

17 Pat Robinson, “Those St. Louis Blues! How They Sob ‘em,” New York Daily News, October 8, 1928: 235.

18 The Sporting News, October 25, 1934: 1.

19 The National League Boston Braves played as the “Bees” from 1936 through 1940.

20 Edgar G. Brands, “Between Innings,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1936: 4.

21 Author’s note: Hartford had become a franchise in the Bees’ farm system in 1938. By the end of 1944, the Bees were appointing their sixth manager (including both Jack and Ed Onslow) in seven years. Hartford seemed to have issues with both its fans’ expectations and its players’ attitude — a difficult situation for a manager to deal with. The Hartford Courant’s sports section had a column titled “With Malice Toward None.” The September 19, 1940 column, in its entirety, praised Onslow for the way he handled the 1940 season. The July 24, 1941, column, following Onslow’s resignation, blamed him totally for the deteriorated situation. Onslow’s argumentative and thin-skinned nature were not likely to do well in so fickle an atmosphere.

22 Onslow was still making public speaking appearances in 1949, when he became manager of the Chicago White Sox. With Stengel now Onslow’s adversary (as manager of the New York Yankees), Onslow had no hesitation to blame Stengel for his troubles in Hartford. Jack could both sell tickets—and hold a grudge. Bill Lee, Hartford Courant, January 4, 1949: 13.

23 Author’s telephone conversation with Bill and Sue Collins, November 2, 2018.

24 Burns, Ed, “’Dead For’ Old Man Slides Home at 59,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1949: 6.

25 Jack Ryan, “Sparks Fly Between Jawing Jack and Firecracker Frank,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1949: 9

26 Richards, Lane’s favorite for the job, was now managing the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League and would not be available until the following season.

27 Leland Beckford of the Acton Beacon wrote a long poem about Rolfe and Onslow’s hunting ventures titled “The Story of Chief Fall-in-the Woods,” on January 15, 1946: 2.

Full Name

John James Onslow

Born

October 13, 1888 at Scottdale, PA (USA)

Died

December 22, 1960 at Concord, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.