Jackie Hernández

Cuban shortstop Jacinto “Jackie” Hernández played in 618 major-league games from 1965 through 1973. He was a full-time starter in just one year: 1969, with the Kansas City Royals, then a new expansion club. The best stretch of his career came in autumn 1971 as he earned a World Series ring with the Pittsburgh Pirates. As Pirates beat writer Charley Feeney said in 1975, “There is one thing that nobody can take away from Hernández. In the pressure games in 1971 and in the playoff against the Giants and the World Series against the Orioles, he played outstanding defensive baseball.”1

Cuban shortstop Jacinto “Jackie” Hernández played in 618 major-league games from 1965 through 1973. He was a full-time starter in just one year: 1969, with the Kansas City Royals, then a new expansion club. The best stretch of his career came in autumn 1971 as he earned a World Series ring with the Pittsburgh Pirates. As Pirates beat writer Charley Feeney said in 1975, “There is one thing that nobody can take away from Hernández. In the pressure games in 1971 and in the playoff against the Giants and the World Series against the Orioles, he played outstanding defensive baseball.”1

Hernández originally signed as a catcher but was built more like a shortstop at 5-feet-11 and 165 pounds. He had the speed and arm to make the transition, though at times he was erratic. He was a skilled bunter — his specialty, he said with a grin in 2011 — but a light hitter, batting just .208 with 12 home runs at the top level.2

Jacinto Hernández Zulueta was born on September 11, 1940. His given name (Hyacinth in English) was difficult for many people in the U.S. to pronounce, leading to his Anglicized nickname; he was also called simply “Jack.”

Hernández’s birthplace was Central Tinguaro in the province of Matanzas. A central, in Cuba’s bygone economic era, was a giant sugar-mill complex linked by rail with other plantations and sometimes the sea. The head of the family, Tomás Hernández, was a fogonero (fireman or stoker), responsible for the running of the locomotives in Tinguaro.

The second-youngest of nine children, Jacinto was preceded by Prudencio, Tomás, Juan, Angela, Cármen, Sobeida, and Urbano; the baby of the family was Ricardo. As of 2016, five were alive: four lived in Cuba and Jackie was in Miami, Florida. The children’s mother, María Prudencia Zulueta, was a housewife. Unfortunately, Tomás Hernández passed away when Jacinto was but 11 years old. María Prudencia was forced to go out and get a job cleaning houses; three children were still living at home.

Societies within a society, the centrales typically had baseball facilities for the workers’ recreation. As a youth, Jacinto served as bat boy for the Tinguaro team for ten years. His family loved the sport, especially his mother, who was a fan of the Havana Lions of the Cuban professional baseball league. At least two of his brothers had baseball talent too. The eldest, Prudencio Zulueta (known as “Chino”), played baseball in the Pedro Betancourt amateur league, reputedly the best in Cuba.3

The third-youngest brother, Urbano Gregorio, was signed by the Havana Sugar Kings, then a Cincinnati Reds affiliate. Urbano never played a game professionally, though. “My brother was an outfielder with the Sugar Kings when he hurt his leg in 1959,” as Jackie remembered in 1968. “The Redlegs sent him to Mexico.”4 There Urbano played with the Sugar Kings’ academy. Upon his return to Cuba, however, he ended his baseball career.

Growing up in the countryside, Jacinto and his friends played baseball in the potreros (cow pastures). Forming their own league and teams, they played whenever there was daylight. Jacinto dropped his school books off as soon as he got home. Although his father did not always approve, his mother was most supportive. The boys, often barefooted, used guava wood bats and cardboard gloves, with cigarette packs taped together for baseballs. Sometimes a small piece of rock in the center of the ball lent it the necessary firmness. Uneven and pocked with holes (and dotted with unsavory obstacles), the potreros often caused bad hops, which forced Hernández to learn to react and play his position better.

Miguel Asso, a typical Cuban scout, observed Hernández playing in the potreros. Asso recommended him to Julio “Monchy” de Arcos, the part-owner and general manager of the Almendares Alacranes (Scorpions), one of the four teams in the Cuban professional league. Soon after, Hernández was invited to an open tryout in Santa Cruz del Norte, a city on the north coast of Cuba, midway between Havana and Matanzas. In 1960, he was signed to a contract for $700, which was given to Jackie’s mother.

Two other future big-leaguers were also present at that tryout. One was Paulino Casanova, called “Paul” during his U.S. career. The catcher had been signed previously, but only for one year, so he was again trying out. He had known Jacinto since they were children from the same area. The other, Dagoberto “Bert” Campaneris, was told that he was too small to play and to try again later. In 1967, Cuban catcher Enrique Izquierdo, also from Matanzas, remembered “seeing all of them play when they were starting out in my hometown. They were all good then.”5

The Pedro Betancourt league, long a stepping stone to the majors for many young Cuban players, was canceled in 1959. Thus, as an 18-19 year old, Hernández played in the Cuban Amateur league and the Interprovincial league — mainly as a catcher. He had a batting average of .382 during the 1960 summer season.

After signing with Almendares, Hernández did not get the opportunity to play for the Scorpions during the winter season of 1960-61. He rode the bench because high-caliber Cuban pro baseball had few open spots. Only native Cubans played that winter, the league’s last before Fidel Castro’s regime abolished it. Previously, each team had typically carried several imported players from the majors or Triple-A. Still, even without that extra competition, a first-year player found it next to impossible to break in. Casanova, for example, never got into a single game during two seasons on the Almendares roster. Hernández stood even further down the catching depth chart behind Izquierdo and Jesús McFarlane.

After the Cuban pro league was shut down, Hernández’s brother Urbano advised him not to pursue a career in baseball. But Jacinto was determined. With his mother’s support, he left Cuba for the U.S. via Mexico. In February 1961, the day after the season ended, he and several other players, including Casanova, secured a visa through the Almendares team at the Mexican embassy in Cuba. Most of the Cubans who had contracts with U.S. teams made the difficult decision to leave their country and their families to pursue their baseball career. In many cases, they did not return until years, even decades later.

Hernández had already become a member of the Cleveland Indians organization. Monchy de Arcos, the Alacranes GM, also functioned as the Indians’ head scout in Cuba. Following a two-day stay in Mexico, Hernández reported to the Cleveland spring training camp in Daytona Beach, Florida, from which he was assigned to the Dubuque (Iowa) Packers in the Midwest League (Class D).

The young man faced two formidable obstacles. First was the language barrier. Second, and worse, was discrimination against people of color, which he encountered en route to Iowa from Florida. Jim Crow laws prevented him from eating with his teammates in restaurants, although at least on that three-day trip, lodging was not an issue; all the players regardless of color slept on the bus, which made no overnight stops. Once out of the South, things were different. Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana, the three states in which the Midwest League operated, were not segregated. In Dubuque, Hernández was assigned to lodge at the YMCA because of his limited income. With him were two other Cubans, Héctor Cárdenas (younger brother of Leo Cárdenas) and Orlando Centellas. Other players were living elsewhere, but Hernández found that color did not affect where he stayed — he had no further problems of that type that year. Still playing catcher, he played in 108 games in 1961 and hit .274.

At the end of his first season, Hernández talked with his mother about the possibility of returning to Cuba. “Don’t come back!” she admonished him. “Things are getting worse, and if you return, you may never be able to leave again.” Comforted, supported, and reassured, Hernández opted to stay.

For the 1962 season, Hernández moved up to Cleveland’s Class B affiliate in Burlington, North Carolina. He was still a catcher, but one day during spring training, Hoot Evers (who was assistant to Indians GM Gabe Paul) asked him to take a shot at playing shortstop.6 Hernández said what one would expect from any confident young man: he could and would play anywhere. He played 88 games at shortstop that season with a fielding percentage of .940.

That same year Hernández met Ida Singleton, who was born in Philadelphia and raised in St. Petersburg, Florida. They were married on March 2, 1966, and later had a son, also named Jacinto, who played professional jai alai for 13 years in Miami. Ida passed away in 2013 after a marriage of 47 years. Hernández missed her a great deal.

Like many other players of the time, Jackie played winter ball to keep his baseball skills sharp and augment his salary. However, unlike Latino players from other nations, he could not go home to play baseball and see his family in Cuba, given the political realities of the Castro regime and the absence of professional baseball. Plus, starting in the winter of 1962-63, a mandate from Commissioner Ford Frick prevented Latino players from playing winter ball in countries other than their own. This was especially unfair to Cubans.7

In 1963, his third year in the minors, Hernández was promoted to the Class AA Eastern League. He played for Charleston (West Virginia), mostly at short, though he still caught in 20 games. With the bat, he reached a professional high by hitting 10 homers. He then went on to play winter ball, first in Venezuela’s Occidental League and then with the Estrellas Orientales in the Dominican Republic.8 Apparently Frick’s edict may not have been as stringent on minor-leaguers.

Hernández remained in Charleston for the 1964 season and improved his average from .235 to a respectable .260. He was still a part-time catcher — but this was his last year behind the plate.9

The year 1965 was a pivotal one for Hernández, now a full-time shortstop. Indians management had assured him that if he made and remained at the AAA level, they would pay him $500 a month (a $200 increase). And so, playing for the Portland Beavers in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, he asked for his promised raise. Cleveland management reneged, and after being rebuffed again, Hernandez told the team to send him a ticket — he was going home. Instead, in May, the California Angels organization purchased his contract and sent him to their AAA affiliate in Seattle.10 In retrospect, Hernández thought it was the best thing that happened to him. Even better, when he arrived in Seattle, they called him into the office, praised him as the best shortstop in the league, with a great arm, and gave him the $200 a month raise the Cleveland club had promised.

On September 6, 1965, a few days before Hernández turned 25, Seattle manager Bob Lemon told him to report to the office. A bit worried, he entered — but the team’s GM advised him to pack up: he was going to the big leagues. “In the clouds,” Hernández took full advantage of his taste of the majors. He got two singles in six times at bat in six games and played a total of four errorless innings.

To start the winter of 1965-66, Hernández played in Nicaragua for the Bóer Indians. He finished that season, however, with Cardenales de Lara in the Venezuelan league. His most treasured memory of Venezuela came in a game that took place not long after he arrived. On December 14, at Barquisimeto, Hernández, never known as a slugger, hit three home runs in a game. That was a first for the Lara ball club.11

Hernández returned to the majors in 1966, and though he stayed on the big-league roster for the whole season, his action was limited. In 58 games, he got just 23 at-bats and had but one hit. He scored 19 runs, however, because he was used frequently as a pinch-runner. The Angels’ regular shortstop, All-Star Jim Fregosi, encouraged Jackie with praise. Hernández ended up playing five different positions that year: short, third, second, and even a few innings in right and center field.

Hernández spent another winter with the Lara club. On April 10, 1967, California sent him to the Minnesota Twins as the player to be named later in the deal that had brought Dean Chance to Minnesota the previous December. The Twins had a fellow Cuban at shortstop, Zoilo Versalles, who had won the AL batting title and MVP award in 1965. Hernández thus went back to Triple-A to play for Minnesota’s affiliate in Denver. With the Bears, he played 112 games at short and regained his hitting stroke, with a .269 average. The Twins called Hernández back up in early August, along with Hank Izquierdo. Originally supposed to be around for only two weeks while Rod Carew did his Marine reserve training, Hernández stayed for the rest of the season. He got into 29 games during the exciting 1967 AL pennant race, playing at both short and third base.12

After the 1967 season, Versalles was traded to Los Angeles. Coming off another winter in Venezuela, this one with Tigres de Aragua, Hernandez won the Twins’ starting job at shortstop in 1968. However, he struggled with both bat (.176 in 199 at-bats) and glove (25 errors in 79 games at short). From late July through early September, he was back in Denver.

Minnesota made Hernández available in the expansion draft that October, and the Kansas City Royals selected him with the 43rd pick overall. Soon thereafter, he played winter ball in a new place: Puerto Rico. His team, the Ponce Leones, won the league championship in the 1968-69 season.

Heading into the 1969 big-league season, Hernández said, “I’ve got something I didn’t have last year. That is confidence. And if you don’t have it, you can’t play.” Acknowledging he wasn’t a good hitter — “No power, you know” — he nonetheless looked forward to helping the Royals. Manager Joe Gordon talked about some of the sensational plays that Hernández had made and said, “If he just slows down a little bit, he’ll become steadier.” Jackie admitted, “I try to rush too much.”13

Hernández went on to appear in 145 games for Kansas City, starting 139 of them. Both were by far big-league career highs for him. In the field, he committed 33 errors. He hit a modest .222, with 4 homers and 40 RBIs, plus 17 stolen bases. He also toyed again with the idea of becoming a switch-hitter late that season.14

Back in Puerto Rico in 1969-70, Jackie’s manager was old teammate Jim Fregosi, in his first stint as a pro skipper. Ponce repeated as league champs, so Hernández got to go to the Caribbean Series, which had been revived after a nine-year hiatus. In Caracas, Venezuela, the Puerto Rican team faced off against the region’s other winter-league champions, and finished second with a 4-4 record.

One of Hernández’s teammates that winter was Wayne Simpson, the powerful righty whose brilliant pitching had been a big part of the Leones’ success. Recalling Hernández’s tremendous range and strong arm, Simpson said:

He reminded me a lot of another shortstop whom I played with in 1970-72, Dave Concepción in Cincinnati. Balls hit on the ground over my head, at my head, through my legs that I knew were hits into center field — Jackie was there to catch them. I didn’t know how at the time, but I came to realize he really knew the game. He was the soul of the club, keeping everybody loose, but an intense competitor.15

Returning to the Royals in 1970, Hernández still played more shortstop than anybody else for the team that summer, but he started just 65 games. The team also used Rich Severson and Tommy Matchick frequently at short; Bobby Floyd and Paul Schaal also got some action there. Hernández posted another mild batting line: .231-2-10 in 238 at-bats.

Kansas City looked for another shortstop, and on December 2, 1970, they got Freddie Patek from the Pittsburgh Pirates. It was a canny deal for the Royals because Patek became their regular at short through 1979. As part of the six-player trade, Hernández went to the Pirates, who still had veteran shortstop Gene Alley, but Alley was battling shoulder and knee problems. The great Roberto Clemente had put in a word with the Pittsburgh front office about getting Hernández, because Clemente had seen him in the Puerto Rican league.16

Alley also suffered a broken hand in spring training in 1971, so the Pirates needed Hernández.17 That spring, the manager of the Baltimore Orioles, Earl Weaver, asked Pittsburgh skipper Danny Murtaugh who his shortstop would be. When told it would be Jackie, Weaver said bluntly, “The Pirates can’t win the pennant with Hernández at shortstop.”18 When asked for comments by others, Jackie chose to say nothing, but remembered that everyone was very upset. However, Weaver would have to eat his words.

As the season progressed, Clemente staunchly supported Hernández. According to Charley Feeney, some of the Pirates lacked confidence in Jackie and begged Gene Alley to play through the pain in his joints. Clemente told the team, “We kiss the rear end of the shortstop who doesn’t want to play when we should be kissing the rear end of the shortstop who wants to play.”19 Hernández also remembered how Clemente bolstered his morale after a crucial misplay in an August game at Cincinnati. “When I got to the dugout, I was crying,” Jackie said. “Clemente put his arm over my shoulder and said, ‘No, no. You don’t need to do that. We back you up here.’ After that, my head was up every minute.”20 Charley Feeney also told that story in late September 1971, after Hernández’s strong play had helped the Pirates down the stretch.21

Another notable moment during Hernández’s first year in Pittsburgh came on September 1, 1971. Murtaugh happened to write out an all-black lineup, the first ever in the majors. In addition to Hernández, batting eighth, the lineup consisted of Rennie Stennett (2B), Gene Clines (CF), Clemente (RF), Willie Stargell (LF), Manny Sanguillen (C), Dave Cash (3B), Al Oliver (1B), and Dock Ellis (P). Hernández remembered that Murtaugh faced questions afterward, inquiries he and other players thought inappropriate. However, the manager said that he was simply playing those he felt gave the Pirates the best chance to win. “We were all Pirate ballplayers,” remembered Hernández in 2016, “and the response by Murtaugh that we were going to win with that lineup was outstanding.” The Pirates did indeed win that night, 10-7.

The united and inspired Pittsburgh team won the National League pennant in 1971. In their victorious four-game National League Championship Series with San Francisco, Hernández played all but three innings. Pittsburgh then defeated Baltimore to become world champions.

Hernández would never forget his World Series experience. He started six times and played in all seven games. He got four hits in 18 times at bat and also stole a base. However, his flawless play in 24 chances in the field made him most proud. “He made the routine plays. He made the tough plays,” wrote Charley Feeney. “If you know Hernández,” Clemente chimed in, “you have to be happy for him. He is a sentimental guy. He loves this game so much.”22

Hernández also started the play that ended the Series, smoothly fielding Merv Rettenmund’s bouncer up the middle and throwing to Bob Robertson at first. Nearly 40 years later, he still got fired up about it. “I wanted that ball!” he shouted. “I wanted to make that last out. Ain’t nothing better than that in baseball. That was the best thing that ever happened in my life in baseball.”23

That winter, Hernández was part of Ponce’s third Puerto Rican championship in four years. However, he never got to play in the postseason again as a big-leaguer. Pittsburgh won the NL East again in 1972, but Gene Alley played every inning at short in the championship series, which Cincinnati won in five games.

In his reserve role with Pittsburgh, Hernández’s playing time diminished each year from 1971-73 — from 88 games to 72 and then 54. In July 1973, the Pirates acquired an even lighter-hitting glove man, Dal Maxvill, to play short. Still, Hernández accepted his reduced role gracefully, saying, “I enjoy myself here more than I have in my career . . . they are the best bunch of guys I have ever played with.”24

Hernández’s major-league career ended after the 1973 season. Although Alley retired, Pittsburgh decided that the young Dominican shortstop Frank Taveras was finally ready to stay in the majors. So the Pirates traded Jackie to Philadelphia in January 1974 for catcher Mike Ryan. He got the news in Puerto Rico, where he was playing with a different team, the San Juan Senadores. That proved to be Hernández’s last of six seasons in that league. Overall, he hit .260 in 1,244 at-bats, with 7 homers and 99 RBIs.

The Phillies released Hernández in the spring of 1974. He returned to the Pittsburgh organization as a free agent, still confident about making it back to the majors. “I can outplay some of them they have up there now,” he said.25 He spent the season with Pittsburgh’s Triple-A team in Charleston, West Virginia, where he had played a decade before. He hit .199 in 155 games. Also with the Charlies that year was Wayne Simpson, who remembered musical fun off the field. “We would get together on off days and relax, play the congas all day, and when we were on the road we would play all night, using whatever we could to make the right sound.”26

Hernández played in Mexico in 1975 after getting a call from his good friend Panchón Herrera. Herrera, another fellow Cuban, had played for the Phillies in the late ’50s and early ’60s. He had become manager for Cardenales de Villahermosa. Reuniting with his friend, Hernández hit .246 with 4 homers and 35 RBIs. He remembered being named the league’s best shortstop that year. The Villahermosa franchise did not operate during the 1976 season because of economic problems. So Hernández played instead with the Tecolotes of Nuevo Laredo, where he hit 9 homers, unusually high for him, and drove in 45. However, he hit just .212.

Hernández returned to Venezuela in the winter of 1976-77, playing for the first time there in nine years. He got into 37 games with Águilas del Zulia, batting .215 in 37 games. That brought his totals for four Venezuelan seasons to .239 with 11 homers and 60 RBIs in 164 games. At the age of 37 in 1977, Hernández went on to play in the Dominican Republic. It was in a summer league, for a team called Arroceros de San Francisco, owned by Julián Javier and managed by Roberto Peña. After that, his playing career finally ended.

Though Hernández was out of professional baseball for about two decades, he became involved with children’s baseball (1987-1997). He also held a series of driving jobs for about 20 years. In 1990, his mother passed away, and he was thus able to return to Cuba for the first and only time. He was there five days to pay his respects and visit with the family he had last seen in 1961.

During 1997, Jackie signed up to work with young players and prospects at old friend Paulino Casanova’s baseball academy in Miami. In March 2010, SABR member Nick Diunte devoted one of his regular columns to “Paul’s Backyard,” as the academy became affectionately known for its location. He praised Casanova and Hernández for their vigor, love for the game, keen eyes, and relaxing, encouraging nature.27 Hernández’s direct involvement with the academy continued through 2013, although he continued to visit regularly as time would permit. Other former major-league players such as José Tartabull and Cholly Naranjo also worked alongside Casanova, imparting their baseball knowledge to youngsters and current major-leaguers who visited as well.

Hernández also returned to pro ball in 1997. He had been keeping in shape by playing in an over-40 league when yet another longtime friend and fellow Cuban big-leaguer approached him. That was Miguel “Mike” Cuéllar, who had become pitching coach for the Duluth-Superior Dukes in the independent Northern League. Soon after, Jackie joined the Dukes, working with them through 1998. He then went on to coach with three other indie-league teams:

- Waterbury (Connecticut) Spirit — Northeast League (1999-2000)

- New Jersey Jackals — Northern League (2001-02)28

- St. Paul Saints — Northern League (2003-06)

With this experience Hernández became the manager of the Charlotte County Redfish, one of six teams in another independent circuit, the South Coast League. His old Pirates teammate Manny Sanguillen said that he always thought Hernández should be a skipper somewhere.29 However, the Redfish floundered on the field, and midway through the season Hernández was reassigned to a position at the league level. He was replaced by Cecil Fielder, who had been the SCL’s roving hitting instructor.30 The league lasted only for that single 2007 season.

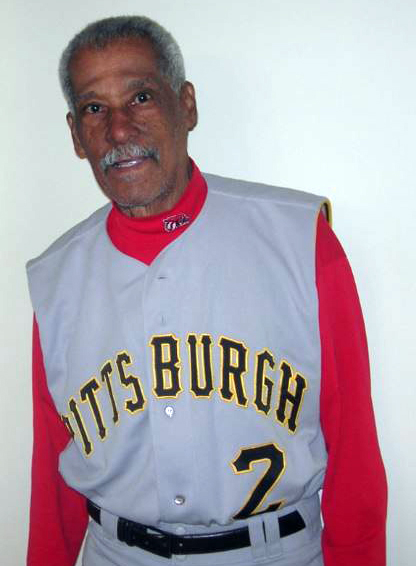

As of 2016 — when the photo at right was taken — Hernández continued to work (alongside Dave Cash and other former major-leaguers) at the Pirates training camp in Bradenton, Florida. He tutored players in the art of playing shortstop. He began making that contribution to baseball in 1999. The day of the second interview for this biography, he was kind enough to drive down (with his friend Victor Lamotte, a fellow Cuban who helped him on occasion) directly from the Pirates training camp. He was still wearing his team uniform. Also with Jackie, as they were everywhere, were his beloved companion dogs Nichy and Rocky.

As of 2016 — when the photo at right was taken — Hernández continued to work (alongside Dave Cash and other former major-leaguers) at the Pirates training camp in Bradenton, Florida. He tutored players in the art of playing shortstop. He began making that contribution to baseball in 1999. The day of the second interview for this biography, he was kind enough to drive down (with his friend Victor Lamotte, a fellow Cuban who helped him on occasion) directly from the Pirates training camp. He was still wearing his team uniform. Also with Jackie, as they were everywhere, were his beloved companion dogs Nichy and Rocky.

Not long before his 79th birthday, Hernández felt significant pain in his back. He was diagnosed with cancer, which had started in his lungs and metastasized. He died on October 12, 2019; Manny Sanguillen broke the news via Twitter. Hernández was cremated and his remains were placed next to Ida’s.

Baseball was Jackie Hernández’s life. He left Cuba to pursue his dream to play ball and take care of his mother. It was a wonderful life and experience, and he had no complaints. This lighthearted man, who always enjoyed joking around with both teammates and opponents, also expressed his philosophy neatly in 1973: “As long as you stay happy, there’s nothing to worry about.”31

Acknowledgments

Continued thanks to SABR members Jorge Colón Delgado (Puerto Rican statistics) and Bob Hurte, and to Wayne Simpson.

Photo Credits

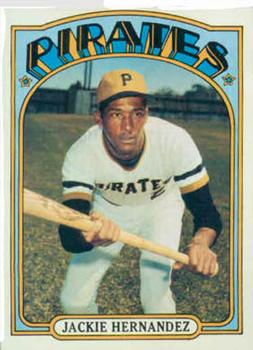

The Topps Company, 1972. Hernández in 2016: taken by José Ramirez.

Sources

Personal interviews

Jacinto (Jackie) Hernández with José Ramirez, January 20, February 5, February 29, March 31, and May 16, 2016. Sr. Hernández was most appreciative that SABR saw fit to write his biography.

Books

Benítez, José A. Crescioni. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997.

Rico, Oscar. Legendarios del baseball. Miami, Florida: R&F Publishing, 2003.

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor. Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, 11th edition. Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 2011.

Internet resources

purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics)

Notes

1 Charley Feeney, “Reynolds Makes a Hit in Buc Shortstop Skit,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1975, 11.

2 Joe Capozzi, “Ex-Pirate Jackie Hernandez, a captivating champion who made a lasting impression on me,” Palm Beach Post, August 8, 2011. The front of Hernandez’s 1972 Topps baseball card shows him squared to bunt, as does the little cartoon on the back of his 1974 Topps card.

3 For reasons unknown to Jackie in 2016, Prudencio used his mother’s family name rather than Hernández.

4 Arno Goethel, “Hernandez Clear Winner in Twins’ Shortstop Derby,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1968.

5 Max Nichols, “Cubans Izquierdo, Hernandez Add New Zip to Twins’ Bench,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1967.

6 Goethel, “Hernandez Clear Winner in Twins’ Shortstop Derby”

7 See also SABR’s biographies of Tony González and Tony Taylor.

8 Fernando A. Vicioso, “Eagles Soaring on Stout Wings of Buc Curvers,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1964, 20.

9 Hernández stood ready as an emergency catcher in the majors but the need never arose in a game.

10 “Jack Spring Is Purchased by Cleveland,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 19, 1965, 14.

11 Eduardo Moncada, “Hernandez Flexes Muscles, Ties Mark with 3 Home Runs,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966, 27. They were also the only three homers that Hernández hit that winter. As of 2014 (the latest data available), 20 men had achieved this feat in the Venezuelan league.

12 “Jack’s Tabbed,” Associated Press, August 5, 1967.

13 Joe McGuff, “Kelly Speed Demon in K.C. Garden,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1969, 25.

14 Joe McGuff, “Royals Plan Switch for Hernandez’ Bat,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1969, 15.

15 E-mail, Wayne Simpson to Rory Costello, April 15, 2016.

16 Capozzi, “Ex-Pirate Jackie Hernandez.”

17 Ken Rappoport, “Jackie Making Alley’s Seat Uncomfortable,” Associated Press, April 14, 1971.

18 Charley Feeney, “Playing Games,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 28, 1971, 23.

19 Charley Feeney, “The Unsung Winners,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 9, 1976, 15.

20 Capozzi, “Ex-Pirate Jackie Hernandez.”

21 Feeney, “Playing Games.”

22 Charley Feeney, “Jackie’s Stock Up at Short,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 19, 1971, 16.

23 Capozzi, “Ex-Pirate Jackie Hernandez.”

24 Andy Nuzzo, “Hernandez Just Happy to Be in Uniform,” Beaver County (Pennsylvania) Times, May 2, 1973, D-2.

25 “Hernandez Confident,” The Sporting News, May 25 1974, 34.

26 E-mail, Simpson to Costello, April 15, 2016.

27 Nick Diunte, “Baseball lives in ‘Paul’s backyard,’” Examiner.com, March 28, 2010 (http://www.examiner.com/article/baseball-lives-paul-s-backyard).

28 The Northern League absorbed the Northeast League in 2001.

29 Telephone interview, SABR member Bob Hurte with Sally O’Leary of the Pirates Alumni Association on July 4, 2012, reflecting her discussion at a lunch with Manny Sanguillen not long before.

30 Scott Adamson, “Fielder replaces Hernandez as Redfish manager,” Independent Mail (Anderson, South Carolina), June 16, 2007.

31 Nuzzo, “Hernandez Just Happy to Be in Uniform.”

Full Name

Jacinto Hernandez Zulueta

Born

September 11, 1940 at Central Tinguaro, (Cuba)

Died

October 12, 2019 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.