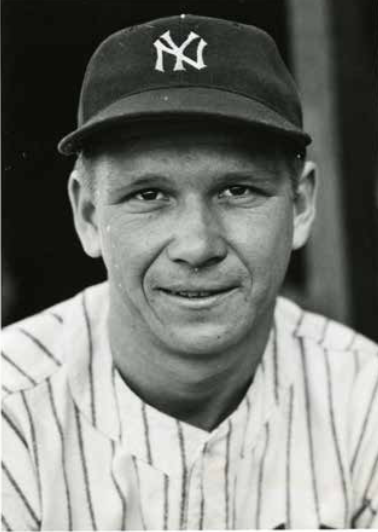

Jerry Priddy

Jerry Priddy’s life went from pinstripes to prison stripes.

When second baseman Priddy and shortstop Phil Rizzuto came up to the Yankees together in 1941, Priddy “was the hotshot of the pair,” sportswriter Milton Richman wrote. “He was smart in the sense that the chances were good he would succeed in anything he undertook.”1 But Priddy failed in New York and Hollywood. He failed on the PGA tour. His failure at extortion put him behind bars.

After the Yankees traded him, manager Joe McCarthy said, “Priddy is the best ballplayer I ever let go.”2 Priddy did turn into a productive player with a slick glove, high on-base percentage, and decent bat, but he never lived up to the stardom that was predicted for him.

Priddy was tarred as a clubhouse lawyer, a term that meant “troublemaker.” To sportswriters of the day, a clubhouse lawyer was any player who said anything besides “I’m just so happy to be here.” But Priddy had an unfortunate knack for rubbing people the wrong way, especially people in authority.

Gerald Edward Priddy was born in Los Angeles on November 9, 1919, to Gerald Howard Priddy and the former Beatrice Briggs. Although the son was usually called Gerald or Gerry in newspaper stories, he preferred “Jerry.”

His father worked as a shipping clerk for a hardware company until he was accused of theft and fired. “After a year and a half, after we’d been living on beans and rice, the company discovered the real culprit and asked my father to come back to work,” Jerry said. “They gave him a raise and tried to make amends for their error.”3 Decades later Jerry would claim that he, too, was wrongly accused.

Young Jerry preferred tennis to baseball because he didn’t like the ball stinging his hand. A reluctant convert, he became a star second baseman and pitcher at Washington High and in Junior American Legion ball. When Yankee scout Bill Essick offered him a contract, he signed because his family needed money. He left school at 17 to go to Class-D ball in Rogers, Arkansas, in 1937.

Priddy was an immediate success. A right-handed batter, he hit .336 with 25 doubles, 10 triples, and 10 home runs, then went home to finish high school. He met Rizzuto the next year at Class-B Norfolk, and they were the prodigies of the Piedmont League. Rizzuto, two years older at 20, hit .336 to Priddy’s .323. (Rizzuto was believed to be 19; like many players, he lopped a year off his age.)

They rose together in 1939 from Class B to the highest minor-league level, Double-A Kansas City. Even in the loaded Yankees farm system, the heavenly twins were surefire stars in the making. They were roommates on the road and practically inseparable on and off the field. One writer quipped that Priddy’s high-school girlfriend, Evelyn Herberger, agreed to marry him only if he promised that Rizzuto would not come along on the honeymoon.

Priddy was just under 6 feet tall, weighing 170 to 180 pounds, blond and self-assured. Rizzuto, 5-feet-6, was a timid Brooklyn boy who became the butt of jokes. If an older teammate told him to order a soup sandwich, he’d do it. Priddy was his protector and mentor. “He was a natural-born leader,” Rizzuto said. “He felt he was as good as anybody on the ball field. Even better.”4

The 1939 Kansas City Blues were one of the strongest minor-league teams in history. Managed by Billy Meyer, they won 107 games, the most by any American Association team in a 154-game schedule. The Blues had their own DiMaggio, Vince, who hit 46 home runs. Priddy led the team with a .333 batting average and led the league in total bases with 44 doubles, 15 triples, and 24 homers. Rizzuto’s .316 average came with less power, but 33 stolen bases.5 Their sparkling defense dazzled the league. Both led their positions in double plays, and Priddy topped all second basemen in putouts and assists.

But these were the Yankees, winners of four straight World Series. There was no room for the phenoms on the major-league roster, so they went back to Kansas City in 1940 and did it all again. The team set a league record for double plays. Priddy batted .306/.383/.493 with 38 doubles, 10 triples, and 16 homers. Rizzuto was even better: .347/.397/.482 and 35 stolen bases. He was named American Association MVP and The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year.

The Yankees slipped to third place in 1940, a humiliation that called for radical change. Even before spring training the club handed the shortstop job to Rizzuto, replacing Frank Crosetti and his .194 batting average. But what to do with Priddy? Yankee second baseman Joe Gordon was coming off a 30-homer season at age 25 and was considered the AL’s best on defense.

Manager McCarthy made his opinion of Priddy clear when he traded first baseman Babe Dahlgren during spring training. McCarthy shifted his All-Star second baseman to first, opening a spot for the prize prospect. “I have no doubts about Priddy,” the manager said. “Mark my words, New York fans will go nuts over Gerry and Phil.”6

From the moment Priddy put on pinstripes, his cocky attitude got him into trouble. “That first day he walked into the Yankee camp,” Rizzuto recalled, “he went over to Joe Gordon and told him, right to his face, that he was a better second baseman than him.”7 The two rookies were threatening the jobs of popular, proven Yankees, so the other players shunned or hazed them. When they were shoved aside in batting practice, Rizzuto took it and said nothing, but Priddy talked back. Before long Joe DiMaggio stood up for Rizzuto, leaving Priddy to bear his teammates’ resentment.

The 1941 season opened with Gordon at first, Priddy at second, and Rizzuto at short, but both newcomers showed early jitters. Priddy was uncharacteristically shaky in the field and was hitting .204 after his first 27 games. Rizzuto stood at .246 the same day. Gordon was uncertain and unhappy in his new position. With the Yankees one game under .500 on May 15, McCarthy gave up on his experiment and benched both rookies.

Rizzuto went back into the lineup when Crosetti was spiked a few days later and stayed there, except for military service, for 11 years. Priddy stayed on the bench. He thought he deserved a shot at the first-base job when another rookie, Johnny Sturm, failed to hit, but McCarthy gave him only a handful of games there. Priddy did get some playing time at third when Red Rolfe got sick, but he batted only .213 in 56 games. McCarthy thought the great expectations might have overwhelmed him.

Rolfe, who had chronic colitis, was not ready for Opening Day in 1942. Priddy took his place for the first 17 games, but batted just .229 with three extra-base hits. Back on the bench, he grew frustrated and sulky. By the end of the season he had raised his average to .280 in 59 games and was begging McCarthy to trade him. The manager, who had no use for malcontents, obliged, though he acknowledged he might be making a mistake.

In January 1943 the Yankees swapped Priddy to Washington. The deal raised questions because, with World War II underway, a player’s military draft status was more important than his batting average. At 23, Priddy was prime draft bait since he and Evelyn had no children. (Evelyn was pregnant with the first of three.) Washington manager Ossie Bluege, with fingers crossed for luck, described Priddy as “the man who’ll be the making of our infield. And he’ll give us that long ball we’ve needed for years.”8

The Senators had been hit harder by the draft than any other team in 1942. With their two best players, Cecil Travis and Buddy Lewis, in the Army, the team finished seventh. When other clubs began feeling the pinch as draft calls grew in 1943, owner Clark Griffith said, “The rest of the league is coming back to us.”9 Washington climbed to second place, albeit 13½ games behind the Yankees.

Given a regular job, Priddy batted .271 with a .709 OPS, better than average, and played his usual sterling defense. He also brought the pinstripe mystique to Washington. “Having Jerry Priddy at second base made the difference,” outfielder Bob Johnson said. “You know, Priddy isn’t a great ballplayer. But the son-of-a-goat’s a Yankee.”10

After the season Priddy’s draft number came up. Even in the Army Air Force he couldn’t get away from Joe Gordon; they wound up on the same team at Hickam Field in Hawaii. Playing ball was Priddy’s primary occupation during his two years in the service.

Returning in 1946, Priddy gave the Senators about average offensive production, then fell off a cliff in 1947. His batting average dropped to .214 as the club sank to seventh place. He won praise as a smart, hypercompetitive player, but some teammates resented his take-charge personality. He and first baseman Mickey Vernon had a fistfight in the clubhouse. “Get this straight,” Priddy told a reporter. “I play to win. If I’m dogging it I expect to get told off; if the other guy’s loafing he’s going to hear from me and I don’t give a hoot whether he likes it or not.”11

Priddy also had differences with manager Bluege. At one point during the losing season, he refused to sign a public statement of support for the manager — the only player to say no — and told Bluege, “I don’t like you and you don’t like me. I know it and you know it.”12

It was no surprise when the Senators traded Priddy to the St. Louis Browns for infielder Johnny Berardino, but the deal was canceled because Berardino announced his retirement to concentrate on his acting career. So the Browns paid $35,000 for Priddy. That was a surprise; nobody suspected that the cash-poor Browns had $35,000. Owner Bill DeWitt recouped the money when he sold Berardino to Cleveland for a reported $50,000, and Indians owner Bill Veeck talked the Hollywood wannabe into playing another year.

Priddy’s career turned around in the winter of 1947-48. On a barnstorming tour with Bob Feller, he took batting tips from the National League home-run champion, Ralph Kiner. He also had surgery for a sinus ailment that had affected his eyesight. In 1948 he hit .296 with 40 doubles, 9 triples, and 8 homers, adding 86 walks for a .391 on-base percentage. Batting third in the order, he drove in a career-high 79 runs while leading all major-league second basemen in putouts, assists, double plays, chances per game, and errors. At 28 he looked like the player the Yankees had expected him to be. He put up similar numbers in 1949, but the Browns were still losers and still broke.

Somehow Priddy had squeezed a $24,000 salary out of owner DeWitt, making him the club’s highest paid player since Hall of Famer George Sisler two decades earlier. DeWitt remarked later, “He was a fast liver and a big spender.”13 After the 1949 season DeWitt unloaded that salary, sending Priddy to Detroit for pitcher Lou Kretlow and a reported $100,000.

Detroit manager Red Rolfe, Priddy’s former Yankees teammate, slotted him second in a strong lineup, ahead of the 1949 batting champion, George Kell, and outfielders Vic Wertz, Hoot Evers, and Johnny Groth. The Tigers spent much of the summer in first place, but the Yankees caught them in September and finished three games in front. Priddy set major-league records by starting five double plays in one game and turning 150 for the season. He hit .277 with a career-best 13 homers, 104 runs scored, and 95 walks.

Priddy’s offensive production slipped a bit in 1951 while he still played every game and led the league’s second basemen in putouts, assists, and double plays. He had played 386 consecutive games by July 6, 1952, when his season ended with a gruesome injury. Sliding home, he caught his spikes on the plate and broke his right leg and dislocated his ankle. He returned in 1953 to appear in 65 games before the Tigers released him in October.

At 34, Priddy managed for a year at Seattle in the Pacific Coast League, then played in the PCL for two more seasons. He finished his career with the San Francisco Seals under his nemesis Joe Gordon in 1956.

Priddy had long been looking forward to a career in the Hollywood film industry after baseball. As early as 1942 he took an offseason job at the Paramount studio, working on the technical crew for the Bing Crosby movie Dixie. He served as a technical adviser for the 1952 film biography of Grover Cleveland Alexander, The Winning Team, starring Ronald Reagan as the Hall of Fame pitcher.

The finale of The Winning Team is set during the 1926 World Series between Alexander’s St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees. Stock footage of Babe Ruth is seen throughout; he is shown in the Yankee dugout (along with Joe McCarthy, even though Miller Huggins managed the Yankees that season) as well as swinging at a pitch, circling the bases after belting a homer, and trotting down to first after being walked. However, in a newly filmed sequence, #3 is shown coming to the plate and swinging at a pitch. Bob Lemon, who served as Reagan’s pitching coach, said Priddy put a pillow under his shirt and appeared here as The Bambino.

According to the Internet Movie Database, Priddy had unbilled bit parts in three other movies with baseball scenes: The Stratton Story (1949), Kill the Umpire (1950), and Three Little Words (1950). He had hoped to work his way into an executive position, but that opportunity never materialized.

Instead, he tried to make it as a professional golfer. A Los Angeles car dealer sponsored his unsuccessful run on the PGA Tour in 1960 and 1961, but his winnings in his first year totaled only $1,105.54.

In the 1960s he was president of Priddy Paper Products Co., a wholesale distributor, with former outfielder George Metkovich as vice president. By 1973 Priddy was running an advertising and public-relations agency in Los Angeles when the sky fell.

On the morning of June 5, 1973, a man called the Princess cruise line in Los Angeles and warned that there were bombs aboard one of the company’s ships, the Island Princess, which had just left Long Beach for Mexico carrying 850 passengers and crew. The caller said he would reveal the location of the bombs if the company paid him $250,000.

The cruise line called the FBI and ordered a search of the ship. Two mysterious small packages were found, each about the size of a pack of cigarettes. The captain threw them into the sea without looking inside.

The anonymous caller set up a money drop in a garbage can. When Priddy came to pick up the cash (actually a bundle of newspapers), agents arrested him. The drop turned out to be near his office in Burbank. The episode, a model of criminal ineptitude, was over in about eight hours.

“That wasn’t the Jerry I knew,” Rizzuto said. “He was outspoken and hotheaded … but outside of baseball he was a regular guy. He knew a lot of prominent businesspeople. It just didn’t make sense.”14

At trial the prosecutor said Priddy needed money because his business was failing. Testifying in his own defense, Priddy admitted making the phone calls, but said he did it because he feared for his life. He said an unknown man with a Mexican accent had threatened to kill him and his family unless he agreed to serve as front man for the extortion scheme.

The jurors didn’t buy it. They took less than five hours to convict him.

The judge sentenced Priddy to nine months in prison, a remarkably lenient penalty. He could have gotten 20 years. The judge said he took into account Priddy’s spotless record and more than 40 letters, from entertainers Bob Hope and Gene Autry and many former ballplayers, attesting to the defendant’s good character.15

Priddy served 4½ months at Terminal Island federal penitentiary in Los Angeles County. “He called me when he got out of prison,” Rizzuto said, “and he told me if he’d had to spend one more day in there he would have been a hardened criminal.”16

When he was released, Priddy was dead broke. It’s not known how he supported his family for the next six years. On March 3, 1980, he got up from the breakfast table and fell dead of a heart attack. He was 60.

His obituary in The Sporting News began, “Gerald E. (Jerry) Priddy, who spent much of his 11-year major league career denying he was a clubhouse lawyer…”17 Such was his reputation. The reality is that he put up better numbers than Rizzuto — at bat and in the field — in a shorter career, but Rizzuto is the one with a plaque in the Hall of Fame.

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Baseball-reference.com.

Crissey, Harrison. “Baseball and the Armed Services,” in Total Baseball, Second Edition (New York: Warner, 1991).

James, Bill. The Politics of Glory (New York: Macmillan, 1994).

Thackrey, Ted Jr. “Big Potential Eventually Led to Big Problems for Athlete,” Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1980: 32.

Notes

1 Milton Richman, United Press International, “Recalled Priddy as Confident, Shrewd Player,” Independent (Long Beach, California), June 7, 1973: 47.

2 “Marse Joe Rated Priddy ‘Best Player I Ever Let Go,’” The Sporting News, October 29, 1947: 5.

3 Bob Broeg, “Public Microscope Again Focused on Jerry Priddy,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 7, 1973: 3C.

4 Richman.

5 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright. “Top 100 Teams.” Minor League Baseball website, milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=12, accessed April 17, 2016.

6 Dan Daniel, “McCarthy Sees Priddy Tops,” New York World-Telegram, April 9, 1941, in Priddy’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

7 Richman.

8 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, April 2, 1943: 13.

9 Bill Gilbert, They Also Served (New York: Crown, 1992), 83.

10 Red Smith, “Sport Cameos,” syndicated column in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 11, 1949: 57.

11 Frank Finch, “Roller-Coaster Priddy Rolls High Again,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1950: 3.

12 Al Costello, “Priddy Offsets Light Hitting With Fast Thinking,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1947: 5.

13 Broeg.

14 Carlo DeVito, Scooter: The Biography of Phil Rizzuto (New York: Triumph, 2010), 261.

15 Accounts of the case from the Los Angeles Times: John Kendall, “Ex-Major Leaguer Priddy Faces Arraignment in Ship Bomb Plot,” June 6, 1973: 3; “Priddy Convicted of Extortion in Threats to Blow Up Cruise Ship,” December 10, 1973: 3; and United Press International, “Former Yankee Star Held in Extortion Plot,” Progress Bulletin (Van Nuys, California), June 6, 1973: 2.

16 DeVito.

17 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1980: 47.

Full Name

Gerald Edward Priddy

Born

November 9, 1919 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

March 3, 1980 at North Hollywood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.