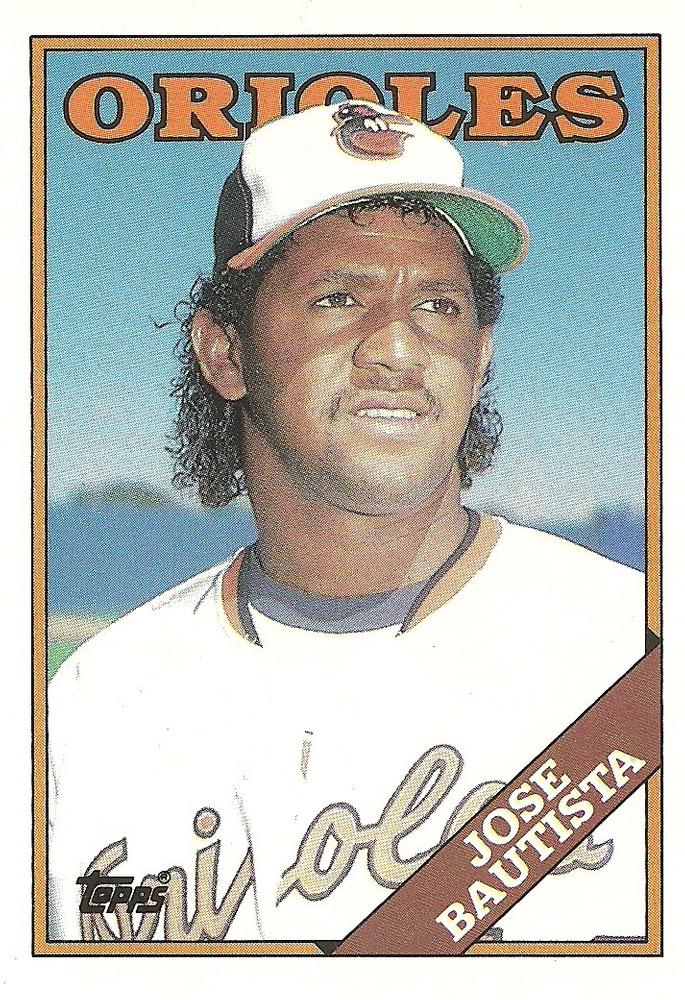

José Bautista

During Welcome Back, Kotter’s run as a popular television sitcom, one of the “Sweathogs” – Robert Hegyes’ fictional Epstein character – routinely identified himself as a “Puerto Rican Jew” to comedic effect. Less than a decade after the show aired its final episode in 1979, a real-life Dominican Jew commenced his nine-season (1988-1991, 1993-1997) big-league career. José Bautista, a resilient right-hander with an effective forkball, spent 40 years in professional baseball as a player or coach and pitched for five major-league teams. Yet, Bautista is primarily remembered for his unlikely Judaism, a faith practiced by less than one-tenth of a percent of the population in his native Dominican Republic.1

During Welcome Back, Kotter’s run as a popular television sitcom, one of the “Sweathogs” – Robert Hegyes’ fictional Epstein character – routinely identified himself as a “Puerto Rican Jew” to comedic effect. Less than a decade after the show aired its final episode in 1979, a real-life Dominican Jew commenced his nine-season (1988-1991, 1993-1997) big-league career. José Bautista, a resilient right-hander with an effective forkball, spent 40 years in professional baseball as a player or coach and pitched for five major-league teams. Yet, Bautista is primarily remembered for his unlikely Judaism, a faith practiced by less than one-tenth of a percent of the population in his native Dominican Republic.1

José Joaquín Bautista Arias was born in Baní, on July 26, 1964. “Not July 25 like it says in most record books,” he clarified.2 He was one of Joaquín and Gloria (Arias) Bautista’s six children before their divorce – four boys and two girls. Including subsequent half-siblings, José was one of 16 children.

Like most Dominicans, Joaquín, a carpenter, was Catholic. But Gloria, who came to the Dominican Republic from Spain as a child, was Jewish. “My father… respected my mother’s religion,” José said.3 “My parents never said, ‘You have to be this.’”4 Among his siblings, José was the most curious about Judaism. “My mama said she could see I was really interested when I was very young,” he recalled. Since anti-Jewish sentiment wasn’t unusual among his peers, he explained, “I was told, ‘Don’t say [that you’re Jewish] … But I had it inside me.”5 He celebrated Hanukkah and remembered his mother lighting candles each Friday night to mark the beginning of the Sabbath. Since Baní – 40 miles southwest of Santo Domingo on the country’s southern coast – did not have a synagogue, José attended services only occasionally on visits to larger cities.

Baseball, on the other hand, was everywhere. Shortly before José’s 13th birthday, Baní’s first major-leaguer debuted: Cincinnati Reds pitcher Mario Soto. “I followed him a lot when I was little,” Bautista said. “I always said I was going to throw harder than him.”6 Four Bautista brothers played the sport professionally, beginning with Ramón, a 17-year-old pitcher when he started in the San Francisco Giants’ chain in 1980.7 The New York Yankees wanted to sign 15-year-old José that same year, but his parents wouldn’t allow it. “I was crying then, too,” he said. “I wanted to be a baseball player.”8

On April 25, 1981, José signed with the New York Mets through scout Eddy Toledo for a $2,000 bonus. “He was a skinny kid and threw only 77 miles an hour, but he had great control,” recalled Mets’ scouting director Joe McIlvaine.9 Bautista explained, “I have all these tires in my backyard… The biggest tire in the middle and four other tires on the corner[s] of the plate. Then I throw the ball through them. That’s where I got my control.”10

As the rookie-level Appalachian League’s youngest player in 1981, Bautista went 3-6 with a 4.64 ERA for the Kingsport (Tennessee) Mets. “I cried every night. I want[ed] to go home, to be with my mother,” he said.11 He spoke almost no English but supplemented what he learned from team-provided classes with postseason night courses in Florida. “I was thinking of what my mother taught me,” he said. “Think big. Think of what’s ahead.”12

Bautista took a step backward when he returned to Kingsport in 1982 – going 0-4 with an 8.92 ERA. In 1983, his 49-year-old mother died, and his career almost ended following a summer in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League. Despite posting a 2.31 ERA, his 44:32 strikeout-to-walk ratio didn’t impress. “The Mets wanted to release me,” he recalled. “But the pitching coach said no.”13

In 1984, Bautista blossomed with a Columbia (South Carolina) Mets club that compiled the Single-A South Atlantic League’s best regular-season record. From June 21 to August 8, he won nine straight decisions.14 He finished 13-4 with a 3.13 ERA and just 35 bases on balls in 135 innings – one of the circuit’s best walk rates. He built on that success with the Lynchburg (Virginia) Mets of the Single-A Carolina League in 1985. Bautista’s 15-8 (2.34 ERA) record included a seven-inning no-hitter on May 26.15 The Mets added the 6-foot-1, 177-pounder to their 40-man roster.

Bautista had debuted with the Dominican Winter League’s Águilas Cibaeñas by making a single appearance two winters earlier, but he spent the entire 1985-86 campaign in the team’s starting rotation. Following a 5-4 (2.71) regular season, he went 2-0 in the playoffs – including a complete game in the Águilas’ triumphant championship series. At the Caribbean Series in Maracaibo, Venezuela, Bautista pitched once for the Dominican Republic, but lost to the host country, 2-0.

Bautista was hit hard for the Jackson (Mississippi) Mets of the Double-A Texas League to begin 1986, so he was demoted to Lynchburg after seven outings and split 16 decisions. In the Dominican League, he went 3-3 with a 5.40 ERA in his first dozen appearances, including playoffs, but when the Águilas defended their title by defeating the Estrellas Orientales, he earned final series MVP honors by winning both of his starts with a 1.59 ERA.

Still, Bautista had no chance to crack the Mets’ big-league roster in 1987 – the defending World Series champions boasted the majors’ top pitching staff. He returned to Jackson and lost his first three decisions while battling arm troubles.16 Bautista rebounded to go 10-2 the rest of the way, though, walking just five batters over his final 46 frames.17 It wasn’t enough to earn a September call-up. “They said I was too young,” he said. “They said I wasn’t ready.”18 In fact, the pitching-rich Mets boasted so many talented arms that Bautista was left off the 40-man roster. “We just couldn’t protect everyone,” McIlvaine explained. “He was [player number] 41.”19

That offseason, Bautista recalled, “[The Mets] didn’t want me to pitch winter ball because they didn’t want any scouts to see me.”20 He joined the Águilas anyway and was deep into an 8-3 (2.95) campaign – leading the Dominican League in victories and winning a Gold Glove – as baseball’s Rule 5 Draft approached. Several teams expressed their interest outright but, unbeknownst to Bautista, Baltimore scout George Lauzerique and coaches Minnie Mendoza and John Hart had also taken notice. On December 7, the Orioles invested $50,000 to draft Bautista second overall – the club’s first Rule 5 selection in a decade. Doug Melvin, Baltimore’s player personnel director, said he expected immediate help based on Bautista’s .639 winning percentage and 2.6:1 strikeout-to-walk ratio over the previous four years.21 Baltimore GM Roland Hemond shared one Dodgers coach’s endorsement, reporting, “[Manny Mota] pointed to his chest and said, ‘The guy has heart.’”22

“This is my big chance,” Bautista said in spring training 1988.23 If he didn’t remain in the majors all season, the Mets planned to reclaim him.24 That summer, Orioles pitching coach Herm Starrette confessed, “I can’t lie to you. I didn’t want to come north with him, but we had to keep him.” Under Starrette’s tutelage, Bautista moved from the right side of the pitching rubber to the left, raised his release point from almost sidearm to nearly overhand, and reduced the upper body movement in his motion. Starrette contrasted Bautista with another Baltimore rookie, Oswald Peraza. “If I tell them to be in the bullpen before a game, Ozzie gets there 10 minutes early and José comes running in at the last minute… José’s a good kid… There’s no fear in him. He’ll challenge the hitters.”25

Initially, Bautista was the last pitcher on the Orioles’ staff. He debuted on April 9, 1988, entering a contest that Baltimore trailed, 9-0, with one out in the third inning in Cleveland. After walking Joe Carter to load the bases, he struck out Mel Hall looking and induced a lineout to escape further damage. Bautista pitched three more innings, allowing single runs in each frame. During Baltimore’s record 21-game losing streak to open the season, he relieved seven times and worked 18 2/3 innings. He moved into the rotation in mid-May and notched his first big-league victory in his second start, throwing seven innings of five-hit ball against the Angels at Memorial Stadium on May 18. On June 24, Bautista outdueled the Red Sox’s Roger Clemens at Fenway Park. By the All-Star break, he was 5-6 with a 4.12 ERA for an Orioles team that was already 31 games below .500. “No doubt, he’s been the most pleasant surprise of the first half,” remarked Baltimore manager Frank Robinson.26

Bautista’s forkball was his best pitch. It broke so sharply that Orioles catcher Terry Kennedy caught only one of Bautista’s last 16 starts because he had difficulties gloving it.27 In August, Bautista posted an AL-best 1.79 ERA, including limiting the Brewers to one unearned run in a complete-game victory. His most impressive performance came in Seattle on September 3. Bautista lost, 2-1, to Mark Langston, but needed only 70 pitches to go the distance on a four-hitter in a contest that was over in one hour and 45 minutes – the quickest big-league game of 1988.28

With 171 2/3 innings, Bautista became the first Baltimore rookie since Tom Phoebus in 1967 to lead the team in that category. However, plagued by the majors’ worst run support in 1988 – 2.72 runs per start – he lost nine of 10 second-half decisions and finished 6-15 (4.30). “He hasn’t gotten the wins, but he’s done a hell of a job,” remarked Robinson.29

Following a reduced winter workload for the Águilas, Bautista entered 1989 with a secure spot in the Orioles’ rotation. “This guy is going to be an outstanding pitcher, and he’s not that far away,” Robinson predicted. “He is much more mature this spring.”30 In Baltimore’s second game of the season, Bautista beat Boston, retiring 18 consecutive batters in one stretch. The Royals took him deep three times in his next outing, though. By May 19, Bautista had allowed an AL-worst 11 homers – two that night in Cleveland after he started despite a bad back. “I didn’t say anything to anyone,” he recalled. “I tried to be tough.”31 Robinson explained his decision to shift Bautista into the bullpen by saying, “His velocity is down. His location is bad. His forkball isn’t good.”32 Instead, the pitcher was placed on the disabled list a few days later.33

On May 29, Bautista began a rehabilitation assignment with the Rochester Red Wings of the Triple-A International League. He returned to the majors on June 17, beating the best team in baseball – the Oakland Athletics – in a nationally televised contest. The next day, Bautista became furious when the Orioles optioned him back to Rochester because they needed a fresh arm. “I took the first one, I took this one, but I’m not going to take anymore,” he said.34 Less than a week later, Baltimore received special permission to bring him back following pitcher Mickey Weston’s injury, but Bautista allowed four homers in two relief appearances and was demoted again on June 30.35 He rejoined the Orioles in September, but appeared in just two lopsided defeats and finished 1989 with a 3-4 (5.31) major league record.

In spring training 1990, a reporter noticed Bautista cautioning younger players not to speak Spanish too loudly in the clubhouse because, “Some players get mad. They think these guys talking Spanish are talking about them. They yell, `Speak English!’” During camp, Robinson cited Bautista as an example of why Major League Baseball should offer more assistance to Latin American players adjusting to the United States. “Even with Bautista, who speaks pretty good English, you don’t know exactly how much he understands,” noted the skipper. “If you ask him if he understands, he just nods.”36

Despite ongoing back problems, Bautista started the season with the Orioles.37 “He has the pitches and stuff to be a starter, but right now… his role with the club is in the bullpen,” Robinson explained.38 After four appearances, Bautista was demoted to Rochester when Mark Williamson came off the disabled list. He lost his first four Triple-A decisions, and remained there for four months, other than a six-day call-up in June.39 After meeting with Bautista’s agent in July, Melvin said, “It was a case of if [Bautista] wasn’t in our plans, could we do something? But, right now, he is in our plans.”40 Bautista went 7-8 (4.06) in 27 appearances (13 starts) for the Red Wings before returning to Baltimore when Williamson broke a finger on August 18. With the Orioles, Bautista was 1-0 with a 4.05 ERA in 22 outings.

In 1991, Bautista made Baltimore’s Opening Day roster as a reliever again. On April 18, he surrendered an 11th inning walk-off homer to Robin Yount in Milwaukee on a pitch the future Hall of Famer described as “a fastball right down the middle.”41 After four appearances, Bautista’s ERA was 20.77, and the Orioles demoted him to the Miami Miracle of the Single-A Florida State League. Citing Bautista’s preference to start, Melvin said, “We didn’t have room for him in Triple-A or Double-A.”42 But Bautista later revealed, “I had an argument with my manager, Frank Robinson. I ran my mouth a little bit. I shouldn’t have done that.”43

In late May, he asked for his release when he was loaned to the Oklahoma City 89ers in the Triple-A American Association – a Texas Rangers affiliate – but it wasn’t granted. After he went 0-3 with a 5.29 ERA in 11 outings, Oklahoma City returned him to Miami. There, aware that a poor performance could end his career, Bautista fashioned an 8-2 (2.71) record. The Orioles purchased his contract, but he pitched just one scoreless inning on August 14, before he cleared waivers and returned to Rochester. “This has been a lost season for me. I want to get it over with and start again,” he remarked.44

Bautista became a free agent and signed with the Kansas City Royals. In 1992, he won his only start in Double-A, but spent the bulk of the season in the American Association, going 2-10 (4.90) for Omaha. That winter, after a three-year absence, he returned to the Dominican League. “I had to,” he said. “It was the only way I was going to go back to the big leagues.”45 He went 4-3 with a 2.93 ERA in 70 2/3 innings (including playoffs) to help the Águilas win another championship. He impressed scout Dan Monzon enough to earn a contract offer from the Chicago Cubs. “I didn’t want to sign him because I had seen him when he was with Baltimore and thought it was the same old [Bautista],” confessed Cubs GM Larry Himes. “But Danny told me he was a different pitcher.”46

That offseason, Bautista married Lea Robitschek, a native of Caracas, Venezuela whom he’d met in Miami. After they started dating, Bautista recalled, “She said, ‘You have to be kidding me. You’re Jewish, too?’” Bautista added, “She’s my big help. She’s my pitching coach at home. She records games on the VCR and points out stuff I’m doing wrong.”47 Bautista adopted Lea’s two previous children, and the couple had two of their own. “I consider all four of them mine,” he said, naming Raquel, Leo, Tammy, and Gloria.48 (Bautista also had a son, José Jr., from a previous marriage.49)

Bautista entered the 1993 season with a 10-20 career record, but he went 10-3 with a 2.82 ERA in 58 appearances (seven starts) for the Cubs. “I did not have any real injuries and, more importantly, I increased my concentration on the mound,” he explained. “Location is the key to my success.”50 On June 11, after Chicago catcher Rick Wilkins was hit by a pitch after placing a hard tag on a baserunner in San Francisco, Bautista was ejected for drilling Giants’ pitcher Trevor Wilson in retaliation. Bautista was suspended for three games, and admitted, “Sure, I hit him. Had to. You’ve got to defend your guys.”51

In July and August, Bautista worked in more than half of the Cubs games. He finished the season in the starting rotation and damaged the Giants’ playoff hopes with his first complete game in five years on September 14. He also stroked an RBI single. “This game was José Bautista. He’s done this for us all year,” raved Cubs manager Jim Lefebvre. Bautista’s ability to start or relieve prompted the skipper to call him “that kind of pitcher who can do everything for you.”52

The Cubs more than quadrupled Bautista’s salary – from $155,000 to $695,000 – and kept him even busier in 1994.53 He saw action in six straight April contests and pitched four straight days in May. With 58 appearances in Chicago’s first 108 games, he led the majors and was on pace to surpass the Cubs’ single-season record of 84 relief outings.54 “They used to tell me I had an elastic arm because I could throw every day and not get hurt,” he said. “Once in a while, I’d get hurt, but I’d still pitch.”55 Pitching coach Moe Drabowsky observed, “He has a very resilient arm… and he throws four different pitches for strikes consistently.”56 Bautista’s strikeout rate of 5.8 per nine innings in ’94 was his personal best, and he issued only 10 unintentional walks in 69 1/3 frames.

When the Cubs’ traveling secretary mentioned that he was observing Shabbat, “Me too” was Bautista’s reply. “No one knew I was Jewish until I was with the Cubs,” Bautista said. “The other players always joked I couldn’t be Jewish. They look at my color and don’t believe it.”57 After Bautista was featured in the New York Jewish Week newspaper that summer, Jewish fans started approaching him. “I’d say, ‘Shalom’ and they’d invite me to their homes,” he said.58 He planned to rest his arm on Yom Kippur – the Jewish day of atonement – in September, but his season ended abruptly when a line drive drilled him in his pitching elbow on August 5.59 Less than a week later, major-league players went on strike, eventually canceling the remainder of the schedule. “I was able to spend time with my family, which I had not had the chance to do before,” Bautista said. He became a free agent and proved his arm was sound in winter ball by making 11 regular season appearances and five playoff starts for the Águilas.

Bautista signed with the Giants after the strike was settled in April 1995. “Chicago offered me a one-year contract, but San Francisco offered me two years,” he explained.60 “Ten years ago, I played the game more out of love than for the money, but since then everything has changed. In the Dominican Republic, you just love to play baseball. In the U.S., they changed all of that and put something else in your mind.”61 Bautista allowed back-to-back homers in his Giants debut, the first of 24 times he was taken deep in 100 2/3 innings. His wife was hospitalized for two months in Venezuela, and Bautista finished with a 3-8 record and 6.44 ERA.62 The more he pressed and overthrew, the less his forkball broke.63 After the season, Giants manager Dusty Baker asked his friend and former teammate Dave Stewart to help Bautista’s mechanics. “[Stewart] gave me an idea how to hold the ball, keep the ball down and make it work,” said Bautista, who posted a 1.88 ERA in four starts for the Águilas that winter.64

In the Giants’ clubhouse, Bautista’s locker was near that of star left fielder Barry Bonds. When Bonds asked if he was going to say, “Good morning” one day when the pitcher felt “kind of like a grouch,” Bautista replied that he was there to work, not to make friends. “From that day on, I was his best friend,” Bautista recalled. “He’d call me in the room and say, ‘Hey, let’s go eat.’”65

In 1996, Bautista posted his lowest WHIP (1.163) as a major leaguer along with a 3.36 ERA in 37 appearances. However, he was experiencing numbness and cold sensations in his right index finger.66 On September 11, he was diagnosed with an axillary artery aneurysm in his throwing shoulder and a blood clot in his pitching hand.67 Bautista was hospitalized for a week, and some doctors told him he would never pitch again.68

In January 1997, Bautista signed with the Detroit Tigers, but he was released in late March and landed in extended spring training with the Mets. Shortly after Opening Day, though, Detroit called back and summoned him to the majors.69 He appeared in 21 games, going 2-2 (6.69) before he was released again on July 21. The St. Louis Cardinals signed him on August 2 and sent him to their Louisville Redbirds affiliate, where he hurled 17 2/3 scoreless innings in the American Association to earn a promotion. Bautista made his final 11 major-league appearances with the Cardinals and finished his big-league career with a 32-42 record and 4.62 ERA in 312 games (49 starts) for five teams.

After posting a 35-31 (3.12) mark over nine seasons with the Águilas (including playoffs), Bautista completed his Dominican League career with the Santo Domingo-based Leones del Escogido that winter by compiling a 4.87 ERA in a dozen relief outings. In 1998, he made three starts for the Yankees’ Norwich Navigators club in the Double-A Eastern League, but his ERA was 15.12. He’d lost about four miles per hour off his fastball since suffering his aneurysm and began contemplating retirement. His wife encouraged him to keep trying, so he caught on with the White Sox organization in June and made 35 appearances for the Calgary Cannons in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. One of his Calgary teammates was a Dominican pitcher who’d idolized him as a youngster, Nelson Cruz. Bautista, said Cruz, “made me more relaxed… helped me deal with depression.”70

Bautista nearly made the Montreal Expos in 1999, but the club acquired Bobby Ayala right before Opening Day.71 Bautista began the year with the Ottawa Lynx in the International League and finished it with the Mets’ Norfolk (Virginia) Tides affiliate in the same circuit. His overall IL ERA was 5.43, similar to his 5.40 mark for the Tigres de Aragua in the Venezuelan League that winter. Bautista’s friend Junior Noboa was surprised when he called asking about a good Mexican League team to join.72 Despite a 5.52 ERA, Bautista led the Sultanes de Monterrey in wins (nine), starts and innings in 2000. His arm felt better than it had since his aneurysm, but he declined an opportunity to pitch his 21st professional season with the Sultanes in 2001. “I said I better stop. I didn’t want to end up with no arm,” he explained. “I didn’t want to pitch any more, and I retired.”73

Although Bautista was in no hurry to begin a coaching career, when his wife encouraged him to assess the demand for his services, the Royals, Marlins, and White Sox all expressed interest within weeks. “Luis Silverio, a coach for Kansas City, said, ‘José, we need you,’ so I said ‘okay,’” he recalled.74 From 2001-2007, Bautista was a pitching coach for Royals’ rookie-level and Single-A clubs in Burlington, Vermont and Idaho Falls. He moved to the White Sox organization in 2008, where his roles included managing the Great Falls (Montana) Voyagers in the rookie-level Pioneer League for part of 2009 and serving as a roving pitching instructor for the organization’s Latin American prospects. Beginning in 2011, Bautista spent nine seasons as the Kannapolis (North Carolina) Intimidators’ pitching coach in the Single-A South Atlantic League, save for 2016 and 2017, when he filled the same role with the Winston-Salem Dash and Birmingham Barons, respectively.

He was scheduled to return to the Intimidators in 2020, but the season was canceled because of the worldwide coronavirus pandemic, ending (at least temporarily) his 40-year professional baseball career. As of 2021, Bautista and his wife reside in Pembroke Pines, Florida. “I wouldn’t change anything about my life,” he said in 2006. “The only thing I would change is me getting older.”75

Last revised: December 6, 2021

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Rod Nelson from SABR’s Scouts Committee for research assistance.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

José Bautista’s Dominican League statistics from https://stats.winterballdata.com/players?key=297 (Subscription service. Last accessed April 12, 2021).

Notes

1 The number of Jews in the Dominican Republic (population 3.9 million when Bautista was born in 1964 and 10.9 million as of 2020) peaked around 1,000 in 1943. Rhonda Spivak, “Sordid Secrets in the Dominican Republic: Dictator Wanted to Take in Jews Fleeing the Nazis to ‘Whiten the Island,’” Winnipeg Jewish Review, January 13, 2012, https://www.winnipegjewishreview.com/article_detail.cfm?id=2002 (last accessed November 14, 2021).

2 José Bautista, Interview with Marc Katz, May 22-24, 2006 (hereafter Bautista-Katz interview).

3 Bautista-Katz interview.

4 George Robinson, “On the Mound with Pride: A Dominican Righthander the Only Jew in Majors?” New York Jewish Week, July 14, 1994: 22.

5 Robinson, “On the Mound with Pride: A Dominican Righthander the Only Jew in Majors?”

6 Bautista-Katz interview.

7 Benny Bautista (b. 1965) was an outfielder/second baseman in the Baltimore Orioles system from 1984-87, and Angel Bautista (b.1967) pitched 23 games for a St. Louis Cardinals rookie-level team in 1984-85.

8 Bautista-Katz interview.

9 Jack Lang, Bill Madden, “Down on the Farm,” Daily News (New York, New York), August 4, 1985: 60.

10 Tim Kurkjian, “Buried by Mets, Bautista Prefers Orioles’ Numbers,” Baltimore Sun, February 23, 1988: 1D.

11 Mike Littwin, “Latins Still Face Major Barriers,” Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), March 25, 1990: 15C.

12 Bautista-Katz interview.

13 Bautista-Katz interview.

14 1988 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 120.

15 “Pirates Endure No Hitter, 2 Hitter,” Washington Post, May 27, 1985: E5.

16 Bill Madden, “Met Prospect for the Birds,” Daily News, December 8, 1987: C28.

17 1988 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 120.

18 Bautista-Katz interview.

19 Tom Verducci, “Sisk is No Longer a Met,” Newsday (New York, New York), December 8, 1987: 149.

20 Kurkjian, “Buried by Mets, Bautista Prefers Orioles’ Numbers.”

21 Tim Kurkjian, “Orioles Obtain Sisk in Trade with Mets,” Baltimore Sun, December 8, 1987: 1D.

22 Kurkjian, “Buried by Mets, Bautista Prefers Orioles’ Numbers.”

23 Kurkjian, “Buried by Mets, Bautista Prefers Orioles’ Numbers.”

24 Kent Baker, “Mets Unlikely to Get Bautista Back,” Baltimore Sun, March 24, 1988: 10D.

25 John Eisenberg, “Peraza and Bautista Give Orioles Hope for Future,” Baltimore Sun, August 8, 1988: 1C.

26 Tim Kurkian, “Robinson: Bautista ‘Most Pleasant Surprise,’” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1988: 5C.

27 Richard Justice, “Tettleton, Traber Lift Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, June 14, 1988: E1.

28 1989 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 128.

29 Tim Kurkjian, “Bautista Meets His Goal, But Not the Win,” Baltimore Sun, August 29, 1988: 3C.

30 Tim Kurkjian, “After Strong Outing, Bautista is Confident,” Baltimore Sun, March 21,1989: 1B.

31 Jorge Milian, “Bautista Yearns for New Start,” Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), August 28, 1991: 12.

32 Tim Kurkjian, “Holton, Tibbs Named Starters; Bautista to Bullpen,” Baltimore Sun, May 21, 1989: 9D.

33 Tim Kurkjian, “Bautista on Disabled List,” Baltimore Sun, May 22, 1989: 3C.

34 Tim Kurkjian, “Bautista Angry, Vows This Will Be His Last Demotion,” Baltimore Sun, June 19, 1989: 3C.

35 Tim Kurkjian, “Bautista Arrives to Provide Relief for Panting Bullpen,” Baltimore Sun, June 24, 1989: 1B.

36 Littwin, “Latins Still Face Major Barriers.”

37 Milian, “Bautista Yearns for New Start.”

38 Peter Schmuck, “Williamson Activated; Bautista Sent Down,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1990: 3D.

39 Patti Singer, “Braves Rally in 10th to Post 2-1 Victory,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), May 12, 1990: 37.

40 Peter Schmuck, “Bautista Asks for Trade; Tired of Rochester Shuffle,” Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1990: 3F.

41 Mark Maske, “Yount’s Homer in 11th Ruins Orioles Day, 4-3,” Washington Post, April 19, 1991: B3.

42 Milian, “Bautista Yearns for New Start.”

43 Bautista-Katz interview.

44 Milian, “Bautista Yearns for New Start.”

45 Bautista-Katz interview.

46 Brian Hanley, “It’s Back to the Bullpen for Castillo,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 7, 1993: 74.

47 Robinson, “On the Mound with Pride: A Dominican Righthander the Only Jew in Majors?”

48 Bautista-Katz interview.

49 1988 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 120.

50 Steven K. Walz, “Making His Pitch,” Jerusalem Post, July 18, 1995: A5.

51 Joe Goddard, “Versatility Bautista’s Value on Cubs’ Staff,” Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1994: 82.

52 “Ex-Oriole Bautista Cuts Giants Down to Size in 7th Loss in a Row,” Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), September 15, 1993: 1D.

53 Dave Van Dyck, “Sosa Files,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1994: 38.

54 As of 2021, the Cubs’ record of 84 relief appearances in a single season is shared by Ted Abernathy (1965), Dick Tidrow (1980), and Bob Howry (2006).

55 Bautista-Katz interview.

56 Robinson, “On the Mound with Pride: A Dominican Righthander the Only Jew in Majors?”

57 Bautista-Katz interview.

58 Bautista-Katz interview.

59 Bill Jauss, “Ex-Son Donn Pall signed; Replaces Injured Bautista,” Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1994: 3.

60 Bautista-Katz interview.

61 Walz, “Making His Pitch.”

62 Henry Schulman, “Stewart Pitches Advice to Bautista,” San Francisco Examiner, February 18, 1996: D6.

63 Larry Stone, “Bautista Gives Up Slam, Then Wins,” San Francisco Examiner, September 6, 1995: C5.

64 Schulman, “Stewart Pitches Advice to Bautista.”

65 Bautista-Katz interview.

66 Nick Peters, “Aneurysm Finishes Bautista’s Season,” Sacramento Bee, September 12, 1996: D5.

67 Henry Schulman, “Bautista’s Future,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1996: 21.

68 Juan Vene, “Bautista Penso Que No Lanzaria Jamas,” El Diario La Prensa (New York, New York), July 20, 1997: 31.

69 Reid Creager, “No Encore Necessary,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1997: 29.

70 Kimberley Todd, “New Cannon Adds Veteran Influence,” Calgary Herald, June 19,1998: C12.

71 Stephanie Miles, “Double-Play Partners,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1999: 73.

72 Efrain Rodriguez, “Aterriza José Bautista,” El Norte (Monterrey, Mexico), March 6, 2000: 7.

73 Bautista-Katz interview.

74 Bautista-Katz interview.

75 Bautista-Katz interview.

Full Name

Jose Joaquin Bautista Arias

Born

July 26, 1964 at Bani, Peravia (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.