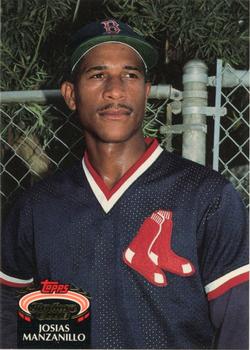

Josías Manzanillo

Dominican righty Josías Manzanillo pitched professionally from 1983 through the winter of 2005-06. He made 41 stops in the professional ranks, with many return trips as he shuttled back and forth between the minors and majors and was traded on numerous occasions. Manzanillo played for eight major league franchises (Mets, Pirates, Red Sox, Reds, Mariners, Yankees, Marlins, and Brewers) and 16 teams in the minors. No fewer than 27 transactions appear on his page on Baseball-Reference.

Dominican righty Josías Manzanillo pitched professionally from 1983 through the winter of 2005-06. He made 41 stops in the professional ranks, with many return trips as he shuttled back and forth between the minors and majors and was traded on numerous occasions. Manzanillo played for eight major league franchises (Mets, Pirates, Red Sox, Reds, Mariners, Yankees, Marlins, and Brewers) and 16 teams in the minors. No fewer than 27 transactions appear on his page on Baseball-Reference.

His long career was mired in setbacks – the most notable being the screaming liner off the bat of Manny Ramírez that struck Manzanillo in his unprotected groin on April 8, 1997. As the pitcher struggled to his feet, surrounded by teammates and medical personnel, none could grasp the true impact of the injury, which resulted in the removal of his testicle. Yet Manzanillo’s strong faith and work ethic enabled him to return to the field a mere month later. The ebullient hurler, who was known for the way he bounded off the mound at the end of an inning, went on to pitch in the majors as late as 2004. Along with his 11 big-league seasons, he played in Mexico as well, while also playing 13 seasons of winter ball in his homeland.

Josías Manzanillo Adams was born on October 16, 1967, in San Pedro de Macoris, Dominican Republic. His parents owned the Mallén bakery to provide for a family that grew to 18 children, though seven did not survive childhood, a sad reminder of the poverty that engulfed the Caribbean nation. Josías contracted baseball fever around the age of 10, infected by his brother Ravelo, four years older, who would also reach the major leagues as a pitcher. Another brother would play in the amateur leagues.

In the city known as “The Cradle of Shortstops,” Josías’s participation in sandlot games typically included a friendly competition over who would play campocorto, an honor thanks to Tony Fernández, Mariano Duncan, and Alfredo Griffin (among others). “I had the skills but could not compete against others at the position,” Manzanillo recalled in 2021. “My brother-in-law suggested I pitch since I was unlikely to surpass the other two shortstops on the team.”1

It wasn’t long before scouts became impressed by his arm. On January 10, 1983, at the recommendation of broadcaster Ramón “Cholly” Naranjo, the Boston Red Sox signed the 5-foot-10, 150-pound teenager to a contract. Naranjo convinced farm director Ed Kenney that Manzanillo, who then possessed an 83-mph fastball, had big-league potential. He would grow a few more inches and pack 40 pounds on the slender frame, enabling him to reach the much-desired 90-mph heat.2 Manzanillo recalled his mother thought he was kidding when she heard the news.

The 15-year-old was assigned to Elmira of the New York Penn League (short season Class A) and reported stateside in March3. His potential was raw because he had not played organized ball for long. By his own admission, he “lacked the knowledge of the game, of the nine against nine, and pitching as a position. I could pitch, throw, but it was the Red Sox who truly taught me to play baseball.”4

Teenage life is always hard, but exponentially more for Latin players whisked away to a foreign land with a different language. Juan Pautt, a Colombian Sox farmhand then at Class AAA, shared some advice Manzanillo took to heart: “You’ve got to learn English.”5 However, the words were accompanied by a deed: the older Pautt took the young Dominican to purchase a dictionary. Years later, Manzanillo would appreciatively recall, “I used to learn two words a day. I used them regularly and I’d use them even if I didn’t use them correctly. I’d keep adding to my words until I could start and finish the conversation.”6 The positive attitude impressed his coaches and peers, but it was very much aligned with Manzanillo’s big-league dreams: “My goal was to play in the big leagues, so I wanted to learn English and the American way, how you do things here. You need to be able to communicate.”7

He labored for three years at Elmira, winning five games, saving two, and losing 12 others in 45 appearances with a 5.73 ERA. A brief callup to the Class-A South Atlantic League in 1985 brought misery, with 18 walks and 13 runs allowed in 12 innings. Manzanillo also failed to impress in his debut in the Dominican winter league, posting a 7.98 ERA in 14 2/3 innings.

Nonetheless, the Red Sox promoted him to the Class A Florida State League in 1986, and Manzanillo responded with a sparking 2.27 ERA in 142 2/3 frames and a professional high 13 victories. He became a starter that year after working mainly out of the bullpen in his first three summers.

Unfortunately, he was injured and appeared in only two games with the Class AA New Britain Red Sox in 1987. The damaged shoulder sidelined Manzanillo for the entire 1988 campaign.8 Nagging injuries and workload concerns prompted the Red Sox to convince Manzanillo not to play in the winter leagues in the late 1980s.

By then age 21, Manzanillo returned in 1989 to post a solid 3.66 ERA in a career-high 147 2/3 innings as a full-time starter for New Britain. He tossed the 100th no-hitter in the history of the Eastern League on July 12, 1989.9 After placing second (1987) and seventh (1988) in the Baseball America organizational prospect rankings, a promotion appeared all but assured. He dreamed: “to be a superstar. I want everyone talking about me the way they talk about Dr. K [Dwight Gooden], like they talk about [Roger] Clemens.” He credits Félix Juan Maldonado, a Puerto Rican minor-league coach, for his development.10

The Red Sox shuffled Manzanillo between Double-A (74 innings, 3.41 ERA) and Triple-A (82 2/3 innings, 5.55 ERA) in 1990. His 1991 campaign was similar (49 2/3 innings, 2.90 ERA in Double-A and 102 2/3, 5.61 ERA in Triple-A). Yet despite the high ERAs for Pawtucket, Boston called him up to the big leagues in September 1991. He appeared in the penultimate game of the season, a 13-4 drubbing against Milwaukee. He tossed the last inning and allowed two hits, three walks, and two runs, driven in by future Hall of Famers Paul Molitor and Robin Yount. Manzanillo would recall being “so nervous I looked like an amateur.”11 Sox coach Luis Aguayo and teammate Luis “Papa” Rivera assisted his transition to the majors.

Manzanillo was granted free agency on March 23, 1992, and signed with the Royals organization on April 3. He threw 7 1/3 innings with the Double-A Memphis Chicks (six runs allowed) and 136 1/3 frames with the Triple-A Omaha Royals (7-10, 4.36 ERA, 1.53 WHIP). The organization cut him loose on October 15, and on November 20, he signed a minor-league contract with the Milwaukee Brewers.

In 1993, Manzanillo pitched in one game with the Triple-A New Orleans Zephyrs (one run, three strikeouts) and in 10 contests with the Brewers (17 innings, 18 earned runs) before a trade to the New York Mets on June 12 for Wayne Housie. Manzanillo pitched well for Triple-A Norfolk, mostly as a starter, and was summoned to the Mets in mid-August. In six appearances, he pitched 12 strong innings (four runs, 11 strikeouts), but his season ended as he hurt his knee fielding a grounder during Darryl Kile’s no-hitter on September 8.12 Even so, he merited strong consideration for a spot in the 1994 roster.

Perhaps triggered by his protracted stay in the minors, Manzanillo developed an odd habit: he would hit his head on the mound and talk to himself. He told reporters, “That’s for me. It’s not nice stuff, what I’ve been saying to myself.”13 The consistent bouts with his confidence for the next decade exacerbated the trait. It was not his only quirk, though. As the New York Times noted, the “naturally exuberant … Mets’ 26-year-old reliever finishes every inning with a flat-out sprint to the Mets’ dugout – head down, legs churning, oblivious to the way his opponents take such a display.”14 After nearly a decade as a professional, he was likely eager to take the mound again and wanted to waste no time walking to the dugout.

In 1994 with the Mets, Manzanillo achieved big-league career highs to that point. He appeared in 37 games and tossed 47 1/3 innings with a 2.66 ERA and a 0.993 WHIP despite spending two weeks on the disabled list with right shoulder inflammation. Mets manager Dallas Green was impressed by Manzanillo, saying, “He’s just going right after hitters right now … what it does is take a little pressure off (closer) Johnnie (Franco) right now.”15 Manzanillo stated, “This is all new to me, but I like the idea of throwing one inning.”16 He faced his brother Ravelo on consecutive days (May 25 and 26 in Pittsburgh) as relievers, though neither one batted against the other.

Across stadiums, the anguish of the strike that prematurely ended the ’94 season drowned the whispers about PED use. When baseball resumed the following spring, the thirst for a feel-good story kept those suspicions repressed. Years later, Manzanillo’s breakthrough 1994 campaign would be examined under more skeptical lenses, as his name was included in the Mitchell Report, linked to that season.

His sharp performance did not carry over into 1995. Manzanillo struggled in 12 games with Mets (16 innings, 7.88 ERA) before being claimed off waivers by the Yankees. He found effectiveness with the Bombers in 11 games (17 1/3 innings, 2.08 ERA) but was again released at the end of the season.

He missed the entire 1996 season after shoulder surgery.17

The Seattle Mariners signed Manzanillo on December 21, 1996. He made the Opening Day roster and appeared in four of the team’s first five games, allowing only one run in five innings. Things were looking up for Manzanillo, though an April 8 game against Cleveland at the Kingdome brought a painfully dramatic turn.

Manzanillo entered the fateful contest in the seventh inning with a man on first and one out. He retired both batters he faced, and the Mariners added two more runs in the bottom half to expand their lead to 14-8, giving the pitcher a solid cushion. In the top of the eighth, the Indians put runners on second and third with one out. That set the stage for Manny Ramírez, only a few years into his career and not yet known for his wild “Manny being Manny” antics. The slugger, however, was already well known for his prodigious power, which opposing pitchers knew and respected.

After he got two quick strikes, Manzanillo’s 24th pitch of the game was ripped right back at him in a split-second. Ramírez’s line drive connected with Manzanillo’s groin and caromed from the mound. Thanks to his reflexes and muscle memory, developed over years of experience, Manzanillo quickly located the ball and fired to home plate, throwing out lead runner Jim Thome, who had tried to score.

Only then, after doing his job, did Manzanillo collapse. Had the sequence occurred in today’s social media and iPhone-saturated atmosphere, it would have immediately been featured on YouTube. In the subsequent years, Manzanillo’s name has been connected to the freak accident, but few remember his remarkable actions to register the out. For a man who is deeply conscious of the mental nature of the game, it was a perfect testament to mind over matter.

He described the pain as “You know when you open the faucet? Inside my body, I just felt draining running inside of me and going into my private parts, and it started getting bigger and bigger and bigger. That’s when I got scared.”18 And despite the modern obsession with exit velocity and launch angles, the play proved that baseball is indeed a game of chance and location.

Rushed off the field and given medical attention, Manzanillo underwent emergency surgery to stem the damage. Had he been wearing a protective cup, his testicle could have been saved. Other players have suffered such injuries (Adrián Beltré, 2009; Carl Crawford, 2010; Juan Uribe, 2016) and undergone emergency surgery, but only Manzanillo lost a testicle.19

He was placed on the 15-day disabled list after his surgery, with a prognosis of being able to resume throwing within that timeframe. Manager Lou Piniella noted the impact on the team, stating, “It’s tough for us, tough for Josías … because he was pitching really well.”20

He returned a scant month later, going an inning in relief of Randy Johnson against Baltimore. He was far from crisp, needing 37 pitches to get through the inning, in which he allowed three runs, two earned. Nonetheless, Manzanillo showcased grit and courage that a box score could not adequately capture.

Seattle released Manzanillo on July 17, but the Astros signed him on July 27. He played in 11 games with Triple-A New Orleans and allowed seven runs. Granted free agency on October 15, he signed with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays on December 18. The season was taxing, and following the injury, he was understandably gun-shy. “Every pitch everybody I faced, I felt like they were going to hit the ball back to me … I was dealing with that, and it was very difficult for me to get over that.”21

Manzanillo began the 1998 season back in the minor leagues, this time with the Durham Bulls, Tampa Bay’s top farm team. Serving primarily as a starter for the first time since 1993, he was 7-6 with one save. However, he was released in the middle of the season. The Mets were interested, and on July 3 signed him for the remainder of the season. With Norfolk, he pitched in 13 games, all but one as a starter, and had a 3.24 ERA. Between the two clubs, Manzanillo tossed 163 innings and struck out 133 batters, both career highs, but he did not receive the much-coveted return call to the majors.

He returned to the big leagues in 1999, tossing 18 2/3 innings as a reliever with the Mets. Although his command was superb (25 strikeouts to four walks), he allowed five home runs and registered a 5.79 ERA (his 4.90 FIP was almost a run lower, but the statistic was not yet broadly used).

New York did not re-sign him after the season. Manzanillo accepted a contract with the Pirates and proved to be a good find. He appeared in 15 games for the Triple-A Nashville Sounds (2.70 ERA, 1.071 WHIP in 23 1/3 innings) and 43 others for the parent club (58 2/3 innings, 3.38 ERA, 1.398 WHIP) in 2000.

Manzanillo was even better for Pittsburgh in 2001. He threw 79 2/3 innings, struck out 80 hitters, appeared in 71 games, and posted a 1.079 WHIP, all career bests in the big leagues. He turned down the club’s arbitration offer, taking his chances in the free-agent market, but no other franchise offered the coveted multi-year contract. Since he had rejected the opportunity to seek an arbitration hearing, he could only sign with the Pirates if the other clubs passed on his services. Manzanillo parted ways with his agent, Brian David, and hired Paul Kinzer.

Although disappointed, Manzanillo did not let resentment affect his personality. Reflecting on the situation, he told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “Things worked out that way. It’s kind of a strange situation. I have to go out there and be the same Manzy if I want to have success … If I try to do more, it can distract me. It’s a general rule: You have to do what you’re supposed to do. If you try to do more than that, it will collapse on you.”22

He re-signed with the Pirates at a lower salary and could not replicate the magic in 2002. He began the season on the disabled list and played in three levels of the organization: a one-game rehab with the Class-A Hickory Crawdads, 15 contests with the Triple-A Nashville Sounds, and 13 with the Pirates. Manzanillo again was prone to the long ball – he permitted five in 13 innings, ballooning his ERA to 7.62. He was released on August 15.

The Reds felt there was some potential. They offered him a minor-league deal in 2003, and after 22 games with the Triple-A Louisville Bats (28 innings, 4.18 ERA), he was called up to Cincinnati. He struggled mightily in nine games (0-2, 12.66 ERA, four home runs in 10 2/3 innings). Manzanillo again played winter ball, this time in Venezuela with the Pastores (Shepherds) of Los Llanos. He saved four games with a sterling 0.96 ERA in 9 1/3 innings.

By then residing in Florida, Manzanillo caught the eye of the Marlins, and the franchise signed him for the 2004 campaign. He saved five games for the Triple-A Albuquerque Isotopes and struck out nine batters in a dozen innings. However, he gave up 15 hits and seven earned runs. The Marlins were nevertheless intrigued; the defending champions had posted a mediocre 83-79 record despite a young rotation with lot of potential and Miguel Cabrera’s first full season, but their bullpen was shaky. Manzanillo had a strong June (10 1/3 innings, one run allowed, one hold, one loss, and one win) but suffered ugly July outings against his former teams (July 6, against Pittsburgh, two runs and a blown save in two-thirds of an inning; and July 9 against the Mets, four runs and his second loss of the season in a third of an inning). He pitched sporadically in August (three games, 2 1/3 innings, three runs) and September (five games, seven innings and seven runs).

Manzanillo’s last major-league appearance, against Philadelphia on September 22, was a pedestrian affair. Inserted in the bottom of the eighth with his team down by nine runs, he tossed the final two innings for the Marlins and allowed three hits, one walk, and one run. He retired Marlon Byrd on a line drive to center field for the final out in the top of the ninth and was removed for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the inning as the Marlins lost, 12-3.

The Red Sox invited Manzanillo to spring training, and as the Boston hopefuls gathered in Fort Myers, Florida in early 2005, club personnel could be forgiven for thinking someone had turned back the clock. Manzanillo was running sprints and working on mechanics with youngsters half his age. He was effusive about the opportunity to return to the franchise that had originally signed him when he was a teenager: “It’s great to be back here. A lot has changed with the Red Sox. But I feel this is where I belong.”23 He added, “There are so many people my age or even younger than me who wish to be where I am … the time that I have been in the big leagues, I’ve always been a guy that can be used in good roles.”24

Though he did not make the roster, closing his major-league career, there was still another stop in Manzanillo’s journey. His 21st year in professional baseball brought him to a new land: Mexico. Failing to generate interest from the major-league franchises, he signed a contract with the Pericos (Parakeets) of Puebla. He won two games, lost five others, and saved an additional five in 38 2/3 innings.25 He was selected to the all-star game, one of six Dominicans to earn the honor.26 Perhaps the true highlight of the experience was playing once again with brother Ravelo, a fitting end to Josías’s summer career.

In 11 years in the major leagues, Manzanillo appeared in 267 games, all but one as a reliever. He won 13, lost 15, and saved six others. He struck out an even 300 batters and walked 153, hitting an additional 18. His 4.71 ERA was in line with his 4.57 FIP in 342 innings. He was slightly better than the big-league average in batting average against (.255 vs. .265). However, his propensity to yield the long ball (3.1% of PAs) and walks (10.2% of PAs) made his OPS worse than average.

Manzanillo coped well with many Hall of Famers, such as Roberto Alomar (1-for-5), Jeff Bagwell (2-for-8), Rickey Henderson (1-for-6), Chipper Jones (1-for-5, his first career round-tripper), Craig Biggio (1-for-6), Barry Larkin (1-for-4), Iván Rodríguez (1-for-4), and Larry Walker (1-for-4). However, he struggled against Mike Piazza (3-for-6). He faced only one opponent, his countryman Sammy Sosa, more than 10 times; Sosa hit 5-for-15 with four home runs. Manzanillo demurred when recalling which batters gave him trouble, noting, “I wouldn’t know how to express that. The game is so mental … I sometimes struggled against weaker hitters, perhaps because of a tendency to let my concentration wander, thinking I already had the match-up won … it happened quite often against the lower third of the lineup.”27

His career on his native soil ended in the winter of 2005-06 and represented his last action as a pro. In two of his 13 campaigns, the Manzanillo brothers anchored the Estrellas Orientales bullpen. He made 116 regular-season appearances, winning 16 games and losing an equal amount, with one save. He also pitched in 36 postseason games, of which five were in the finals (though he was never part of a league champion team).28 His 55 strikeouts led the league in 1997-1998.

In 2007, two years after retiring from the big leagues, Manzanillo’s name popped up in newspapers as one of the players named in the Mitchell Report commissioned on steroid use in baseball. Informant Kirk Radomski claimed to have injected Manzanillo with a substance known as Deca-Durabolin (Nandrolone). Manzanillo admitted to purchasing steroids while playing for the Mets in 1994 but not injecting them. According to his lawyer, “he chickened out or thought better of it.”29 A decade later, Manzanillo was remorseful: “I came from a very, very poor environment. I know I made a mistake when I did that … I regret it then, I regret it today … and the truth is, yes, I did it. But I just did it that one time. Maybe I’m guilty as is because I did it. But I didn’t perform under that.”30

Manzanillo was baptized in 2016 and refocused his attention. “Instead of slapping my head to get those negative thoughts out, reading the Bible helps me understand there’s no need to go that route ever again.”31

Manzanillo was cognizant of his unusual and lengthy career: “I’m amazed I’m still around, but I look around and see people like the John Francos and the Roger Clemenses who have had careers busier than mine. Because I got hurt, I wasn’t able to throw the innings that these guys did, so I feel my body, because I’ve been injured, isn’t used up.”32 He reflects on his long sojourn in the minors not with bitterness but rather a clear mind. “My performance wasn’t up to my ability, and I was able to realize that. It was not the organizations’ fault, but rather mine, due to a lack of confidence.”33

He has found a second career training young pitchers. Manzanillo’s Davie, Florida-based company, The Farm System (previously known as Manzy’s Pitching Farm) nurtures aspiring hurlers by “providing professional baseball training and development (to) give the skillset to stand out and the mindset to succeed.”34

The idea first hatched during his playing days. Former big-leaguer and teammate Bruce Aven had developed a baseball program with the Memorial Hospital West. During the spring training season, Manzanillo participated in a few workshops, and he continued for six years after retirement. In 2011, he and his wife Delmaris (Dee) began the academy, which was still in business in 2022; Josías manages the on-field training while Delmaris administers the business. He prefers teaching youth over joining the professional ranks as a coach, because less pressure is placed on his students. In the Dominican Republic, he notes, “baseball is often a bridge to a better life, not just for the players, but also their families. We play as a necessity but also because we love it … .in the United States, it’s not due to necessity, but rather as recreation. Not everyone has the skills to make it as a professional.”35

Seeing a new generation progress is thrilling to Manzanillo. “To see them develop is my biggest joy. To see kids who don’t know how to hold a glove now be able to play catch … that is priceless. So memorable.”36

Last revised: June 5, 2023

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, quotes stem from the author’s interview with Josías Manzanillo on December 1, 2021.

The author consulted retrosheet.org, baseball-reference.com, and winterballdata.com (Dominican league subscription service) for information on Josías Manzanillo.

Notes

1 Author’s interview with Josías Manzanillo, December 1, 2021.

2 Jayson Jenks, “Josías Manzanillo Story is Much More than a Shot to the Balls,” The Athletic, December 06, 2018, https://theathletic.com/697171/2018/12/06/josias-manzanillos-story-is-much-more-than-a-shot-to-the-balls/

3 Under rules at the time, players as young as 15 could be signed to a professional contract. The current CBA dictates the player must be either at least 16 years old or turning 16 prior to September 1 of the signing period. Specifications can be found at https://www.mlb.com/glossary/transactions/international-amateur-free-agency-bonus-pool-money

4 Author’s interview with Josías Manzanillo, December 1, 2021.

5 Nick Cafardo, “Pitcher Goes Way Back with Sox,” The Boston Globe, March 9, 2005, http://archive.boston.com/sports/baseball/redsox/articles/2005/03/09/pitcher_goes_way_back_with_sox/?page=1

6 Nick Cafardo, “Pitcher Goes Way Back with Sox.”

7 “Josías Manzanillo,” The Greatest 21 Days: Researching the Minor League Players of 1990,” April 24, 2010, http://www.greatest21days.com/2010/04/josias-manzanillo-career-injuries-879.html

8 “Baseball: Around the Minors,” The Sporting News¸May 16, 1988: 38.

9 Chuck McGill, “Minor League No-Hitters,” accessed May 5, 2023.

10 Jayson Jenks, “Josías Manzanillo Story is Much More than a Shot to the Balls.”

11 Glenn Miller, “Retired MLB Pitcher Pitches in Helping Little Leaguers,” Ave Maria Sun, April 7, 2021, https://www.avemariasun.com/articles/top-news/retired-mlb-pitcher-pitches-in-helping-little-leaguers/

12 Tom Friend, “Kile No-Hits Incredible Shrinking Mets,” New York Times, September 9, 1993: B13.

13 Jayson Jenks, “Josías Manzanillo Story is Much More than a Shot to the Balls.”

14 Jennifer Frey, “Baseball: After Manzanillo Strikes, He Runs Like Mad,” The New York Times, July 10, 1994, https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/10/sports/baseball-after-manzanillo-strikes-he-runs-like-mad.html

15 Jennifer Frey, “Baseball: After Manzanillo Strikes, He Runs Like Mad.”

16 Jennifer Frey, “Baseball: After Manzanillo Strikes, He Runs Like Mad.”

17 Some online sites report he played in Taiwan. However, during the author’s interview, Manzanillo confirmed he did not, but his brother Ravelo did, which may be the source of the confusion.

18 Jayson Jenks, “Josías Manzanillo Story is Much More than a Shot to the Balls.”

19 Joe DeLessio, “Baseball Players Who Took Their Chances and Went Cupless: A History,” New York Magazine, March 3, 2013, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2013/03/baseball-players-who-went-cupless-a-history.html

20 “Manzanillo To Be Out Two Weeks,” The Spokesman-Review, April 11, 1997, https://www.spokesman.com/stories/1997/apr/11/manzanillo-to-be-out-two-weeks/

21 Jayson Jenks, “Josías Manzanillo Story is Much More than a Shot to the Balls.”

22 Robert Dvorchak, “Manzanillo pays for his mistake,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 28, 2002. https://old.post-gazette.com/pirates/20020228bucs3.asp

23 Nick Cafardo, “Pitcher Goes Way Back with Sox.”

24Nick Cafardo, “Pitcher goes way back with the Sox.”

25 “2005 Puebla Pericos Statistics,” https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/t-pp13935/y-2005

26 “Seis criollos van al Juego de Estrellas en México,” Diario Libre, May 28, 2005, https://www.diariolibre.com/deportes/seis-criollos-van-al-juego-de-estrellas-en-mxico-DEDL65036

27 https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/luis-rivera/

28 Estadísticas Josías Manzanillo, Liga de Béisbol Profesional de la República Dominicana, http://estadisticas.lidom.com/Miembro/Detalle?idMiembro=6332

29 “Josías Manzanillo,” The Greatest 21 Days: Researching the Minor League Players of 1990.

30 “Josías Manzanillo,” The Greatest 21 Days: Researching the Minor League Players of 1990.

31 “Josías Manzanillo,” The Greatest 21 Days: Researching the Minor League Players of 1990.

32 Nick Cafardo, “Pitcher goes way back with the Sox.”

33 Author’s interview with Josías Manzanillo, December 1, 2021.

34 Company website, https://www.thefarmsystem.org/

35 Author’s interview with Josías Manzanillo, December 1, 2021.

36 Glenn Miller, “Retired MLB Pitcher Pitches in Helping Little Leaguers.”

Full Name

Josias Manzanillo Adams

Born

October 16, 1967 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.