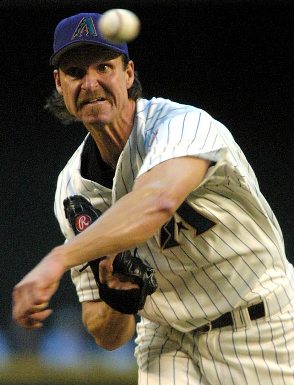

Randy Johnson

Heading into the 2004 season, it seemed as if Randy Johnson had accomplished all he could in his 16-year career. At 40 years old he showed no signs of letting up. He had won five Cy Young awards and was one of only five pitchers to win the award in both the American and National Leagues. He was named World Series co-MVP in 2001 and was tabbed as the starting pitcher for four All-Star Games. He led both leagues in strikeouts and ERA in multiple seasons and led the National League in wins in 2002 with 24. He twirled the first no-hitter in Seattle Mariners history on June 2, 1990. His collection of hardware rivaled the tool department of the local Home Depot.

Heading into the 2004 season, it seemed as if Randy Johnson had accomplished all he could in his 16-year career. At 40 years old he showed no signs of letting up. He had won five Cy Young awards and was one of only five pitchers to win the award in both the American and National Leagues. He was named World Series co-MVP in 2001 and was tabbed as the starting pitcher for four All-Star Games. He led both leagues in strikeouts and ERA in multiple seasons and led the National League in wins in 2002 with 24. He twirled the first no-hitter in Seattle Mariners history on June 2, 1990. His collection of hardware rivaled the tool department of the local Home Depot.

Yet Johnson added one more feat to his baseball immortality. The Arizona left-hander was sporting a 3-4 record heading into a May 18 matchup with the Atlanta Braves at Turner Field. In three of his losses, the Diamondbacks offense had done its own version of molting. But instead of shedding skin, it was runs, as they pushed only three across the dish while Johnson was on the hill in those defeats. The latest was a 1-0 loss to the New York Mets on May 12.

But on this evening, Johnson carried the team on his back, striking out 13 Braves on the way to pitching a perfect game. The Diamondbacks’ offense was by no means explosive, but its two runs proved to be more than enough. “It was like a surreal experience,” said Atlanta’s Chipper Jones. “When you wake up, you think, no, he couldn’t have thrown a perfect game against us. You think it had to be a dream.”1

“A game like this was pretty special,” said Johnson, who reached a three-ball count on only one batter. “It doesn’t come along very often. It didn’t faze me. Everything was locked in. Winning the game was the biggest, most important thing.”2 In the bottom of the ninth inning, Arizona second baseman Matt Kata threw out the first batter. Johnson struck out the next two batters. At the end, pinch-hitter Eddie Perez was overmatched when the last of Johnson’s 117 pitches was clocked at 98 MPH. “This is one of those nights where a superior athlete was on the top of his game,” said Arizona manager Bob Brenly. “There was a tremendous rhythm out there. His focus, his concentration, his stuff, everything was as good as it possibly could be. Everything he’s done to this point pales in comparison.”3

Brenly knew what he was talking about. As of 2014, Johnson was the oldest pitcher by over three years to reach perfection. It was the 17th perfect game in major-league history, and the first since David Cone in 1999.

Randall David Johnson was born on September 10, 1963, in Walnut Creek, California. He was one of six children (three boys and three girls) born to Rollen and Karen Johnson. Rollen Johnson, commonly known as Bud, worked as a police officer and security guard. As a youngster, Randy honed his craft by pitching against the garage door. He tried to emulate another left-handed pitcher, Oakland’s Vida Blue, one of Johnson’s boyhood idols. Even as a youngster, Johnson threw hard, often loosening the nails in the wood siding with one of his pitches. His father would hand him a hammer, “Pound them back in, son,” Bud would instruct him.4

Randy was a two-sport star at Livermore High School, excelling in basketball and baseball. He was drafted by the Atlanta Braves in the fourth round of the 1982 free-agent draft. However, Johnson put the major leagues on hold and accepted a scholarship to play basketball and baseball at the University of Southern California. After two years he left the hardwood behind to concentrate on baseball. Johnson was a teammate of Mark McGwire at USC and learned under the tutelage of the legendary coach Rod Dedeaux. His first appearance in a PAC-10 game, when he was a freshman, came in relief against Stanford, and resulted in an embarrassing moment. “A player on Stanford had just hit a grand slam when Coach Rod Dedeaux called me into the game. He said to me, ‘Do you know what you’re going to do?’ I said ‘Yeah, I’m pitching from the stretch.’ He said to me, ‘Why are you going to pitch from the stretch?’ And I said ‘Because there’s a man over there at first.’ I was looking at Stanford’s first base coach. Dedeaux just looked at me and walked back to the dugout.” 5

After three seasons for the Trojans, Johnson was again selected in the 1985 amateur draft. Montreal picked the 6-foot-10 left-hander in the second round and Johnson signed with the Expos. He ascended through the minor-league chain, making various stops from Jamestown (Rookie League) in 1985 to Triple-A Indianapolis. He had tremendous upside, as he threw a blistering fastball to go with his intimidating stature on the pitcher’s mound. However, he did have control issues (128 walks at Double-A Jacksonville in 1987) and was temperamental (he missed two months of the 1988 season with a hairline fracture in his right hand after punching a concrete wall). Johnson credited coaches Joe Kerrigan and Rick Williams for his development. “Kerrigan was my pitching coach at the Double-A and Triple-A levels of the Montreal Expos’ system and Williams was the roving pitching instructor in the minors. Both of these coaches helped me greatly because they made me grow up and become a better person. They helped me develop into a big-league pitcher. I owe a great deal to them.”6

Johnson made his major-league debut on September 15, 1988, with a win in a start against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Stade Olympique in Montreal. But the Expos were expecting big things in 1989 and traded their prized hurler to the Seattle Mariners for a proven left-handed pitcher, Mark Langston, on July 31, 1989, in a five-player swap. Before leaving the Expos Johnson acquired his famous nickname. During batting practice in 1988, Johnson collided head-on with outfielder Tim Raines. The 5-foot-8 Raines looked up at Johnson and exclaimed, “You’re a big unit.” The nickname stuck.

Johnson made 22 starts for Seattle in 1989, posting a 7-9 record. The next season he served notice of his arrival, when on June 2, 1990, he tossed the Mariners’ first no-hit game. Johnson blanked Detroit at the Kingdome, 2-0. He fanned eight Tigers but also walked six batters. “I’ll never forget this moment,” said Johnson. “When I struck out Mike Heath for the last out, I didn’t know how to react. I just stood there.”7 Johnson had the Tigers off balance for much of the game. “He was throwing completely backwards,” said Detroit second baseman Tony Phillips. “He was throwing fastballs when he should have been throwing breaking balls.”8

But Johnson’s control was still an issue. He led the American League in walks for three straight years (1990-1992). He looked to a highly-placed source for some sound advice. Future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan, then pitching for the Texas Rangers, told Johnson he needed to cut down on his walks as well as develop a secondary pitch to go with his blazing fastball. “I told Randy he could be the most dominating pitcher in baseball if he just worked on his game,” recalled Ryan. “He was a lot like me when I was younger. He was just pitching and not doing a lot of thinking.”9

Johnson also found resolve and courage from another source. Bud Johnson had been suffering with an ailing heart, and he died on Christmas Day of 1992. Randy, who was en route to see his father, missed the opportunity to say goodbye. “From that day on I got a lot more strength and determination to be the best player I could be,” said Johnson, “and not to get sidetracked and not to look at things (in games) as pressure, but challenges. What my dad went through was pressure. That was life and death. This is a game.”10

From 1992 through 1995 the switch was flipped and the Big Unit led the American League in strikeouts four straight years. He joined an elite club in accomplishing that feat during four (or more) consecutive seasons.11 In 1993 he struck out 308 batters, and it was the first of six seasons in his career that he would top 300 strikeouts in a season. He won his first Cy Young Award in 1995 with a record of 18-2, a league-leading 2.48 ERA, and 294 strikeouts. “I got an individual award, but this is a team award,” said Johnson. “Without the success of my teammates, this wouldn’t have happened.”12

The 1995 American League West Division ended in a tie between Seattle and the California Angels. A one-game playoff was played on October 2 at the Kingdome. With Johnson on the hill, the M’s cruised to an easy 9-1 victory and faced the New York Yankees in the Divisional Series. After dropping the first two games in New York, the Mariners evened the series at two wins apiece. Johnson, who had won Game Three, came back to pitch three innings of relief as the Mariners won Game Five, 6-5 in 11 innings. Seattle’s magical season ended in the American League Championship Series, as they lost to the Cleveland Indians in six games. In the clincher, Johnson lost to Dennis Martinez, 4-0.

Johnson had major back surgery in 1996 and started only eight games. He made a full comeback in 1997, posting a 20-4 record and a 2.28 ERA with 291 strikeouts. Twice he struck out 19 batters in a game, against the Oakland Athletics on June 24, a 4-1 defeat, against the Chicago White Sox on August 8, a 5-0 victory. In that game he struck out Frank Thomas and Albert Belle three times each. “Basically, with him I just look for one pitch – his fastball,” said Chicago second baseman Ray Durham. “If he’s getting his slider over, I’m out anyway.”13

Johnson started the All-Star Game in Cleveland on July 8, 1997. In the second inning he uncorked a throw over the head of the Colorado Rockies’ Larry Walker. Walker, a left-handed batter and a former teammate of Johnson’s in Montreal, turned his batting helmet around and hit right-handed to the amusement of all. On the next pitch he returned to the left side of the plate. Walker’s Colorado teammate Dante Bichette said of Johnson, “He’s the most dominating pitcher right now. When he came up, he had that fastball and the strikeouts. But he didn’t have that look in his eye. Now he’s got that possessed look in his eye. If you just look at him you could get intimidated.”14 The Rockies faced Johnson on June 13, 1997, and could manage only two hits and one run against him in eight innings.

The Mariners won the American League West Division by six games over the Anaheim Angels in 1997. Their postseason was short-lived; they were eliminated in four games by Baltimore in the ALDS. Johnson lost both of his starts to Mike Mussina in the series.

Johnson entered the last year of his Mariners contract in 1998. Seattle had committed to long-term deals with Alex Rodriguez and Junior Griffey, so Johnson expected a big payday too. But Seattle management had its doubts about his durability. The 34-year-old ace was a power pitcher who had pitched more than 200 innings in six of the last eight season and had had back surgery. The Mariners looked to trade Johnson even though an estimated 9,000 more fans pushed their way through the turnstiles at the Kingdome every time Johnson toed the rubber.15

Johnson did not take to the constant trade talk well, and his record on the mound (9-10, 4.33 ERA) may have reflected his feelings. At the trading deadline on July 31, Johnson was dealt to Houston for pitchers Freddy Garcia and John Halama and infielder Carlos Guillen. The Astros were atop the National League Central Division by 3½ games over the Chicago Cubs at the time. Adding Johnson instantly made Houston the favorite to take the NL flag. Chipper Jones of Atlanta summed up the feeling of the senior circuit: “I think those were gulps you heard around midnight Friday from Atlanta, San Diego and Chicago. Picking up Johnson has to make Houston the favorite. In a (seven-game) series, you are going to have to face Randy at least twice, which means you may have to win four games against pitchers like (Mike) Hampton and (Shane) Reynolds. Those guys could be Number 1 starters on a lot of other teams.”16

When the news hit of the trade broke, the Astros were in Pittsburgh. First baseman Jeff Bagwell was in a bar across from Three Rivers Stadium with some teammates and club officials. When the word came of the trade, Bagwell bought drinks for everyone in the house. In Johnson’s first start, two days later, he struck out 12 Pirates to get the win. It was the most strikeouts by an Astros left-hander in 29 years. Johnson was as solid as advertised. He went 10-1 with a 1.28 ERA. The Astros won their division by a comfortable 12½ games.

But the euphoria was tempered quickly when San Diego toppled Houston in four games in the Division Series. Johnson lost Game One, a tight 2-1 contest in which Padres starter Kevin Brown rang up 16 strikeouts. Johnson also lost Game Four, surrendering just one earned run in six innings of a 6-1 loss.

The Arizona Diamondbacks, after their inaugural season, wanted to make a splash in the free-agent market. They signed Johnson to a four year, $52 million pact. The return on their investment was substantial. Johnson won the Cy Young Award each season from 1999 through 2002. He joined Pedro Martinez and Gaylord Perry as the only pitchers to win the award in both leagues (Roy Halladay and Roger Clemens followed), and he tied Greg Maddux for the most consecutive years winning the award. On September 10, 2000, Johnson struck out Mike Lowell of the Florida Marlins for his 3,000th career strikeout. On May 8, 2001, he struck out 20 Cincinnati batters. In each of the four years Johnson won the Cy Young Award, he struck out more than 300, topping out at 372 in 2001. He won at least 20 games twice, and won the ERA crown three times. In 2002 Johnson won the “Triple Crown” for pitchers, leading the league in wins (24), ERA (2.32), and strikeouts (334).

But for all of his accomplishments, Johnson always maintained that individual awards meant nothing if the team didn’t win. “The outcome of the game takes precedence over anyone’s accomplishments,” he said in commenting on a loss in 2000. “You can get all the strikeouts you want, but I made a mistake (on a throwing error in the game in which he notched his 3,000 strikeout, a 4-3 loss).”17

Johnson was joined in Arizona by veteran right-hander Curt Schilling via trade during the 2000 season. They were polar opposites: Johnson was a surly, introverted type, Schilling had an extroverted, funny personality. Where Johnson was all business on the mound, Schilling was a bit more relaxed, easy-going. Johnson was quiet, Schilling talked nonstop. They fed off each other to form a fearsome one-two punch in the Diamondbacks rotation. Randy welcomed Curt’s arrival. “What helped most with Curt was that he’s one of the few pitchers who knows the expectations put upon that ace in a rotation of five pitchers,” said Johnson. “So I can share experiences and feelings with him that I couldn’t share with anybody.” 18 Said Arizona first baseman Mark Grace, “Randy is a pussycat, a very, very nice man. He just doesn’t enjoy the spotlight as much as Schilling.”19

Arizona catcher Damian Miller also shared a different viewpoint of Johnson. “Randy puts a lot of faith in me,” said Miller. “He wants me to do whatever I can to get him through seven or eight innings. If I have to yell at him, I yell at him. One thing about Randy: He’s got the three Cy Youngs, but if I’ve got something to say, he looks me right in the eye and listens to it. He doesn’t feel like he’s above his catcher. He wants his catcher to get in his face.” 20

But the Big Unit saved his best for the baseball’s biggest stage, the World Series, in 2001. The Diamondbacks rode Johnson and Schilling (both 20-game winners) to a division crown and a berth in the World Series against the New York Yankees. With the Diamondbacks trailing three games to two, Johnson won his second game, hurling seven strong innings during a 15-2 pasting of the Yankees. Game Seven was much closer, as the Yankees took a 2-1 lead in the eighth inning. Johnson, as he did in 1995, came on in relief and retired all four batters he faced. He was the pitcher of record when the Diamondbacks scored two runs off Mariano Rivera in the bottom of the ninth inning to capture their first world championship. Johnson and Schilling were named co-MVPs of the Series. When Arizona manager Bob Brenly asked Johnson how he felt after Game Six, and whether he would be able to come out of the bullpen for Game Seven, Johnson answered, “This is the World Series, I’ll be ready.”

Johnson signed a new two-year deal with Arizona in 2003, reported at $33 million. The deal made Johnson the highest-paid pitcher in major-league history. But arthroscopic surgery on his right knee curtailed his season (6-8, 4.26 ERA in 2003). He rebounded in 2004 to lead the league in starts (35) and strikeouts (290) while winning 16 games.

Johnson authored a book with Jim Rosenthal titled Randy Johnson’s Power Pitching: The Big Unit’s Secret to Domination, Intimidation and Winning (Three Rivers Press, 2003). The book was written to guide youngsters on how to be complete pitchers. Pitching coaches Tom House and Mark Connor contributed to the manuscript.

After the 2004 season the Diamondbacks sought to cut some salary and knew that it might be a problem keeping Johnson. Johnson was sold to the New York Yankees on January 11, 2005, for pitchers Javier Vazquez and Brad Halsey, catching prospect Dioner Navarro, and $9 million. Johnson won 17 games in 2005 and 2006 for the Yankees, although his ERA ballooned to 5.00 in 2006. Both years the Yankees won the American League East Division. However, they were bounced from the division playoff round both years, with Johnson failing to register a win. “When Randy came here, he didn’t have the same stuff he used to have,” said Yankee closer Mariano Rivera. “Randy only pitched here as a visitor and maybe he wasn’t comfortable. He’s the only one who really knows. But he worked, worked hard. We didn’t win as much as we wanted to, but I know every time out there, he pitched as hard as he could.”21

After the 2006 season, Johnson had lower-back surgery and was sold back to the Diamondbacks for four players on January 9, 2007. But more back surgery limited Johnson to 10 starts in 2007.

After an 11-10 season in 2008, Johnson signed a one-year deal with the San Francisco Giants. He got his 300th win as a Giant, against the Washington Nationals on June 4, 2009. It was a game that was unlike others earlier in his career; he pitched six innings and struck out only two. His 13-year-old son, Tanner, served as batboy. “I’m just happy that my family and friends were able to come,” said Johnson. “My son being batboy – those are kind of moments that I relish the most. My family’s been with me the whole time. They’ve seen what I’ve done.” 22 Johnson, who was now 45 years old, quipped that all he needed was 211 more victories to catch Cy Young.

Johnson retired after the 2009 season. In 22 major-league seasons, his record was 303-166 with a 3.29 ERA. He struck out 4,875, second to Nolan Ryan (5,714). He threw 37 shutouts and pitched 100 complete games. He was nominated to the All-Star Game 10 times.

In retirement Johnson surrendered his time to his other two passions: his family, wife Lisa and their four children (Johnson also had a daughter from a previous relationship), and photojournalism. He enjoyed doing the things he missed while playing and enjoyed seeing his children grow up from their teen years. It may seem odd to some that for someone who shunned the camera lens as a player, Johnson embraced it so much as a hobby. But he took classes at USC and applied his skills at various concerts and NASCAR events. He made numerous trips to visit the troops in Afghanistan. Johnson aided many charities, mostly cystic fibrosis where his fundraising efforts have raised more than a million dollars. Occasionally he scheduled appearances at sports memorabilia/card shows.

In 2006 Johnson perhaps took a departure from his rather withdrawn demeanor and appeared in an episode of The Simpsons. The animated show debuted on March 19, 2006, in the 17th season of the series. Johnson played himself in the role.

In 2015, Johnson was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. He was named on 534 of 549 ballots by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

An updated version of this biography appears in SABR’s No-Hitters book (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. Sources Ancestry.com baseball-reference.com/ retrosheet.org/ Johnson’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Notes

Full Name

Randall David Johnson

Born

September 10, 1963 at Walnut Creek, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.