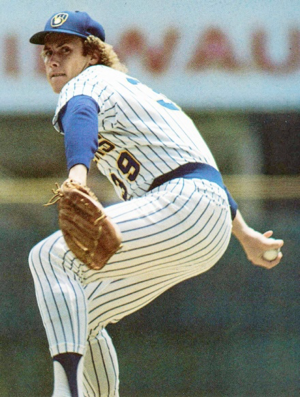

Lary Sorensen

As a pitcher, Lary Sorensen handled plenty of challenges over the course of his successful 11-year major-league career with seven teams. But not even the best-hitting opposing lineup—like the one he faced in the 1978 All-Star Game—compared to the opponent he battled after his playing days: alcoholism. His story resembles an amusement park ride, with highs and lows around every turn. Now, after a lifetime chock-full of thrills and scary moments, Sorensen has embraced sobriety and found serenity.

As a pitcher, Lary Sorensen handled plenty of challenges over the course of his successful 11-year major-league career with seven teams. But not even the best-hitting opposing lineup—like the one he faced in the 1978 All-Star Game—compared to the opponent he battled after his playing days: alcoholism. His story resembles an amusement park ride, with highs and lows around every turn. Now, after a lifetime chock-full of thrills and scary moments, Sorensen has embraced sobriety and found serenity.

Lary Alan Sorensen was born on October 4, 1955, in Detroit, Michigan. His parents, Leonard and Dorothy, picked the non-traditional spelling of his name because they wanted a four-letter name to match his older sister, Lynn, and his stepsiblings (from his father’s first marriage), Gary and Gail.

“Regardless what you might read on the internet, I wasn’t named for [Major League Baseball pitcher] Frank Lary or [Pro Football Hall of Famer] Yale Lary,” said Sorensen, of German Lutheran descent. “My parents didn’t like Lawrence, but they liked Larry, and since the other kids had four letters in their names, they just dropped an ‘r’ out. That’s the way it is spelled on my birth certificate.”

Sorensen grew up in the northern Detroit suburb of Mount Clemens, Michigan. Both parents worked at the vinyl production plant for the Ford Motor Company. His father was in production control, while his mother was an administrative assistant for the plant manager. Dorothy left Ford to work for Detroit Fabrics, which was started by her boss at Ford; the firm bought scrap vinyl from the automaker and sold it to furniture shops and auto repair companies. She wound up becoming a partner.

“I had a nice middle-class upbringing, with a parochial grade-school education at Trinity Lutheran School,” Sorensen said.

Acknowledging that his maternal grandfather, Wilbur Steele, regularly played catch with him and was an important figure in his formative years, Sorensen spent many summer days and nights at the Little League fields near his house. Before he reached the required age of 10 to play, he was a batboy. “At eight years old, I was better than a good number of the guys who were playing,” Sorensen said. He was also a batboy for the Ford Motor Company softball team. By the time Sorensen was old enough to play Little League, his family had moved to a nicer part of Mount Clemens, and at age 12, he was traded from one team to another.

“I was the best player in the league, and one Sunday afternoon, I got a call from my coach, who told me that in order to get his nephew on his team, he had to trade me,” Sorensen said. “It was traumatic. I was in tears. Clearly, I haven’t forgotten about it.”

Sorensen attended L’Anse Creuse High School in nearby Harrison Township, Michigan, beginning in 1969. There, he became a three-sport athlete, playing football, basketball and baseball. He also excelled as a baritone in the choir. Success as a right-handed pitcher, however, wasn’t immediate. “One of my first games as a freshman, I started and walked four guys, and the coach pulled me out,” Sorensen said. While Sorensen became the starting quarterback for his high school football team as a junior and a bona fide scorer and rebounder for the basketball squad, his breakthrough in baseball came playing for amateur teams during the summers. “A friend of the family had a 16-year old who played on a team with the best players from the area high schools,” Sorensen said. “I joined that team [the summer after his sophomore year of high school], and that’s where I really developed and started getting noticed.”

Meanwhile, Sorensen was admittedly “a bit of a troublemaker in high school” and did not play baseball as a junior after being caught for underage drinking. While that dampened interest from professional teams who were considering drafting him, he did receive attention from the University of Michigan, Central Michigan University, and Western Michigan University. He visited Amherst College following the recommendation of an alum who owned Sanders Candy in Michigan and knew about Sorensen. “I really wanted to go to Michigan State, and they said I could come as a preferred walk-on,” Sorensen said. “Michigan offered me two-thirds of a full-ride scholarship, so that made my decision easy.”

Sorensen posted 3-4 and 4-3 records as a freshman and sophomore at Michigan in 1974 and 1975. The summer after his freshman season, he played for an amateur team from Flint, Michigan, that won the Connie Mack World Series championship in Farmington, New Mexico.1 It marked the third of four national titles Sorensen won with summer teams. He was named tournament most valuable player twice—in 1973 (National Amateur Baseball Federation in College Park, Maryland) and 1975 (All American Amateur Baseball Association in Johnstown, Pennsylvania).2

As a junior at Michigan, Sorensen blossomed, going 9-3 to tie the school season wins record, earning first-team All-Big Ten honors, and being named the Wolverines’ co-MVP. Michigan won its second straight Big Ten championship and advanced to the NCAA Tournament Mideast Regional final for the second straight season, losing to host Eastern Michigan University both times.3

On June 8, 1976, the Milwaukee Brewers selected Sorensen in the eighth round of the MLB Draft. “I was pretty sure that I would get drafted,” said Sorensen, who studied speech and journalism at Michigan. “A scout for the California Angels told me there was no way I would get past them in the fifth round, but obviously I did. My coach [Moby Benedict] didn’t want to lose me, but he knew that I would sign for a postage stamp.”

Sorensen embarked on his professional career with the Newark (New York) Co-Pilots in the short-season Single-A New York-Penn League.4 He went 6-2 with a 2.28 ERA in 13 games, including seven complete games and two shutouts among eight starts. Sorensen got a huge break when he was picked to start for the Brewers in the annual Hall of Fame Game in Cooperstown against the New York Mets on August 9.

“Right place at the right time,” said Sorensen, noting that Cooperstown is less than 150 miles east of Newark. “The Brewers didn’t want to waste one of their starters in an exhibition game, so they brought me over. Doubleday Field was a tiny bandbox of a park—something like 270 down the lines—and I gave up a couple of home runs, but I went seven innings and allowed only three runs. Willie Mays had retired from the Mets a couple of years before, but he played in that game and I got to face him. [Brewers owner] Bud Selig was there, as was the general manager [Jim Baumer] and obviously the big-league manager [Alex Grammas] and pitching coach [Cal McLish]. The next day, they told me I was going to Double-A.”

Sorensen was promoted to the Berkshire Brewers (Pittsfield, Massachusetts) in the Eastern League and in seven games went 0-3 with a 3.29 ERA. After playing in the Arizona Instructional League that fall, Sorensen was invited to Milwaukee’s spring training camp as a non-roster player in 1977. He began the year with the Triple-A Spokane Indians in the Pacific Coast League, went 5-5 with a 4.63 ERA in 12 starts and was called up to the parent club.

“I signed my first contract on June 12, 1976, and pitched in the big leagues June 7, 1977,” said Sorensen, who made his debut against the Baltimore Orioles at County Stadium at age 21. He started and pitched 6⅓ innings, allowing four earned runs on seven hits with three walks and three strikeouts, but did not figure in the decision as the Brewers recorded a 7-6 walk-off victory.5 Sorensen earned his first big-league victory in his fourth start, a complete-game four-hitter against the Seattle Mariners in Milwaukee on June 24.

Sorensen spent the balance of the 1977 season with Milwaukee, finishing 7-10 with a 4.36 ERA. He completed nine of his 20 starts. The Brewers lost 94 games—their eighth straight losing season—and, after the season, Selig hired renowned executive Harry Dalton as general manager. Dalton tabbed former big-league pitcher and long-standing Orioles coach George Bamberger as field manager. He retained McLish as pitching coach.

“With George and Cal, it was like having two pitching coaches, but they had totally different ways of saying things,” Sorensen said. “George was from Staten Island and dropped an F-bomb every third word, while Cal was from Oklahoma and wouldn’t say crap if he had a mouth full of it. So, I got all this information, and sometimes the way George said it made sense and sometimes the way Cal said it made sense. But it all clicked in my head.”

The result was a breakout 1978 season for Sorensen, who also credits teammate Mike Caldwell, a veteran left-hander, for helping him evolve. Twice in the first week of June, Sorensen faced the Detroit Tigers—his first two appearances against his hometown team—and pitched complete games. On June 1 he suffered a 4-3 loss at Tiger Stadium, and five days later he was a 5-1 winner at County Stadium. Returning home as a major leaguer was “an out-of-body experience,” Sorensen said. “It was a dream come true; everything you would expect. Al Kaline tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Hi Lary, I’m Al Kaline.’ For one of the few times in my life, I was practically speechless. I was a big Tigers fan growing up, and he was my idol.”

Boasting an 11-5 record at the All-Star break, Sorensen made the AL team for the Midsummer Classic at San Diego Stadium. With his parents and sister in attendance, Sorensen was summoned from the bullpen by manager Billy Martin to start the fourth inning. After allowing a leadoff single to Larry Bowa, Sorensen proceeded to retire nine consecutive NL batters: Reggie Smith, Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, George Foster, Greg Luzinski, Steve Garvey, Ted Simmons, Dave Winfield and Bowa.

“The entire trip was a blur,” said Sorensen, who prior to the game met Gerald Ford, former president of the United Sates and fellow University of Michigan athlete. “I was walking on air that day. I got nine pretty easy outs. It was all pretty amazing—a completely surreal experience.”

Sorensen continued to excel in the second half and finished with a career-high 18 wins (against 12 losses) and a career-low 3.21 ERA. He ranked fifth in the league with 280⅔ innings pitched and 17 complete games among 36 starts. Sorensen explained his success unassumingly: “All I did was throw strikes. I had a good sinker, to go with a fastball, curve and occasional changeup. I was ultracompetitive. I was willing to tackle someone rounding third to prevent him from scoring.”

The Brewers, meanwhile, enjoyed a reversal of fortunes, going 93-69 to finish third in the AL Eastern Division, just 6½ games behind the eventual World Series champion Yankees. And they kindled tremendous fan interest, drawing 1,601,406 fans for their home games, far and away the most in the nine-year history of the franchise to that point.

“There was a brand-new attitude throughout the organization,” Sorensen said. “We were this young, happy-go-lucky bunch that was scoring a lot of runs and having fun. Bamberger was a roly-poly guy who liked to have fun. During batting practice, he would sometimes go out to the parking lots in his uniform and hang out with the fans who were tailgating.”

The 6-foot-2, 200-pound Sorensen continued as a stalwart in Milwaukee’s starting rotation the next two seasons, going 15-14 in 1979 and 12-10 in 1980.6 On July 5, 1979, he authored a two-hit shutout of the Yankees in New York. He walked the leadoff batter, Willie Randolph, who was erased on a double play, and then retired the next 20 batters. Sorensen did not allow a hit until Chris Chambliss singled with one out in the eighth inning; Bucky Dent singled with one out in the ninth.

Sorensen married Patricia (Tricia) Morrissey on October 20, 1979. In November, he was part of a team of major-league all-stars that toured Japan. There were seven games between the AL and NL, and then the two teams combined and played two games against a Japanese all-star team—one in Nishinomiya and the other in Tokyo. That trip was part of the newlyweds’ honeymoon that also included trips to Mexico and Hawaii.

During the 1978 and 1979 offseasons, Sorensen worked as the weekend sports anchor for WTMJ, the Brewers’ flagship television station. “I had a blast and learned a lot about the business,” he said. “It taught me about the composition of stories and how to talk in sound bites. I learned on the job what I probably would have learned my last year at Michigan.”

On December 12, 1980, the Brewers traded Sorensen to the St. Louis Cardinals in a seven-player transaction.7 The deal was “a surprise and disappointing but at the same time exciting because it was St. Louis,” Sorensen said. “Playing for Whitey Herzog was amazing. I learned an incredible amount about baseball from him in just that one season. He did with paper and different colored magic markers what a room full of guys with computers are doing now as far as who hit what off each pitcher where. Whitey was way ahead of things and a master at putting his players in the best position to succeed.”

In his lone season in St. Louis in 1981, Sorensen raced to a 4-0 start—including a four-hit shutout of the Chicago Cubs at Busch Stadium on April 22—before finishing 7-7 with a 3.27 ERA while surrendering merely three home runs in 140⅓ innings. Looking for starting pitching, the Cleveland Indians traded for Sorensen on November 20.8

By the time spring training began in 1982, Sorensen and Tricia were expecting their first child. It proved to be a problematic pregnancy; their daughter, Laura, was born six and a half weeks premature on September 22 in St. Louis. Sorensen spent several weeks traveling between starts from Cleveland to St. Louis, where Tricia had returned to be closer to her obstetrician. Sorensen, admittedly overweight and out of shape, wound up 10-15 with a 5.61 ERA and 251 hits allowed in 189⅓ innings.

Then, Sorensen wistfully watched his two former teams, the Brewers and Cardinals, square off in the 1982 World Series.9

“It was really hard to watch because I had friends on both teams,” Sorensen said. “And when you look at the players I was traded for and the jobs that they did, they were a big part of why both teams got into the World Series. It definitely was bittersweet.”

After rebounding to go 12-11 with a 4.24 ERA for Cleveland in 1983, Sorensen signed as a free agent with the Oakland A’s. Used as both a starter and a reliever, he never got untracked and finished 6-13 with a 4.91 ERA in 1984. Then Sorensen was on the move again as a free agent, this time to the Cubs, who were coming off their NL East Division championship campaign. Primarily a long reliever in 1985, Sorensen went 3-7 with a 4.26 ERA.

“Teams weren’t exactly sure how to use me, and I wasn’t giving them good enough reasons to lock me into one place,” Sorensen said. “I was still valuable because I could do different things, so they kept me around, but being a swingman was really difficult. All the innings I had pitched caught up to me, my arm slot changed, and I lost some velocity and movement, which is a dangerous combination. I lost confidence in myself to a degree. I was bouncing around, and it wasn’t a great period of life in a lot of ways.”

On February 21, 1986, Sorensen and his wife welcomed their second child, son Mark. When information surfaced a week later from the Pittsburgh drug trials, Sorensen was one of 11 MLB players suspended by Commissioner Peter Ueberroth for admitting cocaine use. Sorensen was given a 60-day suspension, which was withdrawn when he agreed to donate to a drug-abuse program and participate in community service.

At the end of 1986 spring training, Sorensen was released by the Cubs, signed with the Phillies, and pitched for their Triple-A Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. On July 24, Philadelphia traded Sorensen to the Montreal Expos,10 and he concluded the season in Triple A with the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association.

Sorensen was back in the majors in 1987, beginning the season with the Expos. He was serviceable—going 3-4 with a 4.72 ERA in 23 games from April through June—but was sent back to Indianapolis and eventually released. Following offseason knee surgery, he signed as a free agent with the Cincinnati Reds and agreed to start the 1988 season with the Double-A Chattanooga Lookouts in the Southern League.

After appearing in seven games—living alone in a motel while Tricia, Laura, and Mark were at home in Chicago—Sorensen asked for and received his release on May 5 and figured his playing days were over. But the San Francisco Giants called; he signed on July 5 and reported to the Triple-A Phoenix Firebirds in the Pacific Coast League. Sorensen impressed with a 2.76 ERA over 14 games, was recalled in August and recorded two saves in 14 games down the stretch. He made what proved to be his final big-league appearance on September 24, 1988, against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“[Former Cardinals teammate and longtime friend] Bruce Sutter told me to pitch until every team tells you ‘no,’” said Sorensen, who was released by the Giants at the end of spring training 1989. “I think that happened. When I got released for the last time, it wasn’t a good experience, and there were no jobs available. My arm didn’t feel great—I was actually trying to throw a knuckleball—so I decided that was enough.”

For his major-league career, Sorensen compiled a 93-103 record with a 4.15 ERA, 69 complete games, and 10 shutouts in 346 games (235 starts), amassing 1,736⅓ innings. Known for his control, he averaged just over two walks per nine innings.

It did not take long for Sorensen to flourish in a second livelihood: broadcasting. He started with SportsChannel Ohio, announcing Cleveland State University baseball games in 1989, and a year later moved on to ESPN, where he was an analyst for the College World Series (1990-92) and MLB games (1990-94). Sorensen then moved to radio, first as a morning drive-time anchor on WDFN in Detroit in 1994 and then calling Tigers games with Frank Beckmann on WJR from 1995 to 1998. He also worked as the sideline reporter for Michigan football games for several seasons.

“Growing up, my two goals were to be a major-league baseball player and to have Ernie Harwell’s job,” Sorensen said, referring to the Tigers’ Hall of Fame broadcaster. “By the time I was 40, I had done both.”

Possessing a pleasant disposition with a quick wit, Sorensen was a fan favorite as a player. Beneath that bubbly persona, however, were demons that led him to alcohol addiction late in his playing career and beyond. “I was getting to be a mess when I was playing, and I knew it, but I wasn’t doing anything to stop it,” Sorensen said. “It got really bad during my years [broadcasting] with the Tigers, and I feel really bad about that. I let a lot of people down. It should have been a lifetime job, and I blew it. It was a struggle for a long time after that.”

Between 1992 and 2004, Sorensen was arrested six times for driving under the influence and twice spent time in jail.11 He and Tricia divorced on October 20, 2003, their 24th wedding anniversary, and his relationship with Laura and Mark also deteriorated. But Sorensen continued to drink, and on February 2, 2008, police found him slumped over the steering wheel of his car on the shoulder of Interstate 696 near I-94 in Macomb County, Michigan. He was taken to a hospital and diagnosed with alcohol poisoning. Tests determined his blood-alcohol level to be 0.48—six times higher than the threshold for drunken-driving convictions in Michigan.12 Having violated the conditions of his parole, Sorensen went to Jackson (Michigan) State Prison, where he stayed until December 2009.13

The following winter, Sorensen fell on a patch of ice near his apartment in Grand Rapids— “walking home from Walmart with my groceries because my driver’s license was suspended”—severely injuring his left shoulder. Needing major surgery and substantial rehabilitation, he turned to the Baseball Assistance Team for financial support. BAT had been formed in 1986 by a group of former MLB players to help members of the baseball family who needed assistance with nowhere else to turn. “In order for me to keep getting funding, I had to stay sober, and I slipped,” Sorensen said. “It was about a month after my surgery. I violated the agreement we had, so they shut me off, and I was a mess.”

In February 2011, Sorensen moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to live with his sister and her husband. After moving into his own rented townhouse, Sorensen’s mail carrier, Rick Gfeller, spent a year and a half encouraging him to attend Calvary Baptist Church. Sorensen finally did, in the spring of 2013, and went on to sing in the choir and join a Bible study class. A church usher, Jim Israel, befriended Sorensen and regularly invited him to lunch with members of the community. One of the lunch meetings was with Ron Wellman, the athletics director at Wake Forest University—whom Sorensen had met when he pitched for the Cubs and Wellman was the baseball coach at Northwestern—which led to Sorensen broadcasting Wake Forest baseball games on radio and television in 2014. Another contact, Scott Reed, helped Sorensen get his financial affairs in order and led to a job as a television broadcaster for the Winston-Salem Dash, Class-A affiliate of the Chicago White Sox in the South Atlantic League.

“I started getting in with people who were living life the right way, and I saw how life could be lived,” Sorensen said. “God reached out and told me it was time to make a change.”

Sorensen’s foremost blessing was meeting Elaine Layland, a nurse and hospital administrator, via an online dating service. She was front and center when Sorensen suffered an alcohol-related seizure on January 27, 2014, resulting in a broken back and cracked ribs. The date is significant because it remains the last time he turned to the bottle. “Elaine saw what a train wreck I was, but she stuck with me,” Sorensen said. They were married on February 26, 2014. “Every compassionate bone you can have in your body she had during that time. She’s an amazing woman.”

As his days of sobriety grew, so did Sorensen’s rekindled relationships with his children. Both graduated from Michigan State. Laura has had a career in social work in Philadelphia, while Mark pitched in the Tigers’ minor league system for five seasons before earning a law degree and joining a firm in New York.

“They are incredible children, and Trish did a wonderful job raising them while I was drinking too much during many of their developmental years,” Sorensen said. “Being back in their lives has been an incredible thing. I’m sure there is still some resentment deep down, and deservedly so, but to have them say, ‘Love you,’ is wonderful. I’m proud to say we are a family again, and they have made Elaine feel part of the family. It’s very special.”

Elaine’s career resulted in moves to Kissimmee and West Palm Beach, Florida, and Mill Spring, North Carolina, where the couple has lived since June 2019. Sorensen has continued his broadcasting work for Wake Forest baseball and added football in 2017. In March 2018, he got involved with a startup company, F5 Sports, which produces the pitchLogic baseball that utilizes a computer chip measuring 12 different movements of a pitch and gives instant feedback.14

For several years, Sorensen has promoted the benevolent work BAT does to major-league teams in spring training. “We make appeals to today’s players for contributions by giving first-hand accounts about how there is a baseball family that takes care of its own when there are emergency situations,” he said. “There are a lot of people that helped save my life, and BAT was a big part of that.”

Sorensen is thankful for each and every day and doesn’t take a single one for granted.

“Absolutely,” he said. “I must never forget what I am: an alcoholic. I am not playing a game in which a loss is a temporary setback. I am dealing with my disease, for which there is no cure—only daily acceptance and vigilance. I’m not afraid that I am going to slip, but I don’t want to slip because life is so good right now.”

Last revised: August 28, 2020

Acknowledgements

This biography was reviewed by Jack Zerby and Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

All quotes are from the author’s interviews with Lary Sorensen on April 18, 2020, and June 4, 2020. The two first met in 1981, reconnected in 2010, and have kept in touch since.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com website for player and team pages, daily logs, and box scores, as well as the following:

Schott, Tom. “Card Corner: 1981 Topps Lary Sorensen,” BaseballHall.org, December 10, 2015, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/card-corner/sorensen-smiling-again.

University of Michigan, 2019 Baseball Record Book: 4, 8, 19.

Notes

1 The Flint coach invited Sorensen to play on his team after seeing him play the previous summer in Detroit.

2 Sorensen interviews.

3 Eastern Michigan’s pitching staff included future major leaguers Bob Welch, Bob Owchinko and John Martin.

4 Newark, New York, is located 35 miles southeast of Rochester.

5 The same day Sorensen made his major-league debut, Milwaukee selected future Hall of Famer Paul Molitor with the third overall pick of the amateur draft.

6 Sorensen ranked fifth in the AL with 16 complete games in 1979.

7 Milwaukee also sent outfielder Sixto Lezcano, pitcher Dave LaPoint and highly touted outfield prospect David Green to St. Louis in exchange for pitchers Rollie Fingers and Pete Vuckovich and catcher Ted Simmons.

8 In a three-team deal, St. Louis also sent pitcher Silvio Martinez to Cleveland, which sent catcher Bo Diaz to the Philadelphia Phillies, which sent outfielder Lonnie Smith to St. Louis.

9 The Cardinals defeated the Brewers in seven games in the Fall Classic that became known as the “Suds Series” since it was a showdown between cities renowned for their breweries.

10 Philadelphia also sent infielder Tom Foley to Montreal in exchange for infielder Skeeter Barnes and pitcher Dan Schatzeder.

11 Lynn Henning, “My alcoholism cost me,” Detroit News, January 26, 2007, http://www.motownsports.com/forums/topic/37361-lary-sorensen-tells-his-story/.

12 Neal Rubin, “Lary Sorensen off the bottle, back on the air,” Detroit News, March 7, 2018, https://www.detroitnews.com/story/opinion/columnists/neal-rubin/2018/03/07/lary-sorensen-tigers-wjr-dui/32721531/. According to the National Institutes of Health, death is possible for a person with a blood-alcohol content above .31, per Brant Wilkerson, “Former major-leaguer rebuilding life, broadcasting career in Winston-Salem,” Winston-Salem Journal, April 6, 2014,

13 Sorensen had been on parole from his sixth arrest for driving under the influence since June 2006. He remained in prison until that original maximum sentence ended in December 2009.

14 According to Sorensen, pitchers from every MLB organization are utilizing the pitchLogic baseball, as well as a growing number of colleges and high schools across the country.

Full Name

Lary Alan Sorensen

Born

October 4, 1955 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.