Lew Fonseca

Lew Fonseca was a batting champion, a versatile fielder who played multiple positions, a manager, and a batting instructor. Off the field, he was an accomplished singer, radio announcer, and a film director and producer. But most of all, he was a promoter of and educator for the game of baseball, taking the technical resources at hand to help others better understand the sport he loved. Today, when Little Leaguers watch DVDs so they can learn how to hit, when a college coach spends hours in the film room discovering how to make his team better, when an umpire’s inaccurate call is overturned thanks to a slow-motion replay, even when a designated hitter comes to bat — all of those modern instances got their start, in part, over 80 years ago when Lew Fonseca purchased his first motion-picture camera

Lew Fonseca was a batting champion, a versatile fielder who played multiple positions, a manager, and a batting instructor. Off the field, he was an accomplished singer, radio announcer, and a film director and producer. But most of all, he was a promoter of and educator for the game of baseball, taking the technical resources at hand to help others better understand the sport he loved. Today, when Little Leaguers watch DVDs so they can learn how to hit, when a college coach spends hours in the film room discovering how to make his team better, when an umpire’s inaccurate call is overturned thanks to a slow-motion replay, even when a designated hitter comes to bat — all of those modern instances got their start, in part, over 80 years ago when Lew Fonseca purchased his first motion-picture camera

Lewis Albert Fonseca was born in Oakland, California, on January 21, 1899, the son of European immigrants. Lew’s father, Joseph, a barber, was from Lisbon, Portugal; his mother, Anna, a baker, was from Switzerland. The parents set up their respective businesses in San Francisco, where they raised Lew and his two siblings, Ava and Joseph II. Lew would always remember a night in his childhood when it began raining in his bedroom. The date was April 18, 1906, and the “rain” was actually plaster, falling from the ceiling, as the devastating San Francisco Earthquake began; the Fonsecas ended up sleeping in Golden Gate Park with many others.

As Lew grew into manhood, it became apparent that he was gifted both in athletics and as a singer, with a beautiful baritone voice. Lew gave both talents their due, playing ball on the sandlots during the day with Lefty O’Doul and the San Francisco “Park Bums,”1 then singing in local music halls at night. He enrolled at St. Mary’s College of California, attending classes for dentistry and playing ball for the St. Mary’s Phoenix during 1918-1919. St. Mary’s baseball, under the direction of Brother Agnon McCann, had become a pipeline for a number of major-league baseball players, including Harry Hooper.2 Fonseca’s skills were noted by the San Francisco Seals, who signed him for the 1920 season. But after spring training and only two at-bats, Fonseca moved on. The Seals wanted Fonseca to gain experience with an affiliate in Vancouver, but instead the self-assured young man got himself hired as the player-manager of Smithfield in the outlaw Northern Utah League. There, Fonseca not only won the league batting title, hitting .469, but also made himself a favorite at the local vaudeville house with his singing performances.

In 1921 Fonseca signed with the Cincinnati Reds as a “bonus baby” of sorts. The contract called for him to be paid $1,500 by the Reds, but only if he made the team out of spring training. Fonseca did, starting at second base in the team’s first game of the season; batting against Babe Adams of the Pirates, he hit a single and triple in four at-bats. But Fonseca was soon sidelined with injury. He seemed to have a penchant for running into immovable objects, especially on the basepaths where collisions loomed. Although Fonseca was a good-sized man at 5-feet-11 and 185 pounds, he often got the short end of confrontations.3 In the 1924 season, as an example, he played in only 20 games, hitting .228; his season was wrecked when he ran into second baseman Rogers Hornsby of St. Louis and broke his left arm. After four years with the Reds, he had averaged .301 at the plate, but had appeared in only about 40 percent of the Reds’ games. His Cincinnati career ended on March 30, 1925, when the Philadelphia Phillies selected him off waivers.

Fonseca had continued his singing career while in Cincinnati, appearing in local theaters with the billing “A Better Ballplayer than any Singer — A Better Singer than any Ballplayer.”4 But during his recuperation from injury in 1924, he married Ruth Burr Doolittle, a nurse from San Francisco; this seemed to bring an end to his stage career. The couple had a son, Lewis Jr., in 1925 and a daughter, Carolyn, in 1930.

When Fonseca came to the Phillies in 1925 it seemed that he had finally found a home and a jump-start to his career; in Philadelphia; he was healthy — and hitting. Playing in 126 games, he hit .319 with a .802 OPS.

Despite Fonseca’s efforts, the Phillies were not a good team, and getting worse; they would be a losing team with or without him. The Phillies solution was to offer Fonseca less money — and he balked. So when he stayed home with his $6,000 contract ($500 less than 1925), the Phillies chose a practical solution, sending Fonseca’s rights to the Newark Bears of the International League. Fonseca reluctantly reported to the Bears and soon became the darling of their fans, hitting .381 with 40 doubles and 21 home runs. Newark finished third in the standings but first in attendance. The Bears capitalized on their hot commodity, selling Fonseca to the Cleveland Indians for $50,000 and three players. In 1927 he justified the Indians’ investment, hitting .311 and playing both second base and first base in 112 games.

That winter, back in his home state of California, Fonseca had the opportunity to be an extra in Hollywood movies, including the baseball movie Slide, Kelly, Slide.5 Throughout Fonseca’s lifetime, articles were written about his developing a passion for various avocations; he threw himself into a new interest the same way he threw his body into an obstacle on the field — singing, public speaking, golf, ping-pong, magic tricks, mountain climbing, it didn’t matter.6

Raised on the West Coast with Hollywood in its infancy, and singing in venues where film was part of the undercard, it’s not surprising that Fonseca developed an interest in movies. So when the Stewart-Warner Company decided to stop producing movie cameras, Lew decided to purchase a 16-millimeter version at the $50 sellout price. The new hobby was to change the direction of his life.

Fonseca returned to Cleveland for the 1928 season, but again incurred injuries; while hitting a spiffy .327, he played in only half the Indians’ games. Then in 1929, Fonseca showed what he was capable of when healthy. Playing 148 games, all at first base, Fonseca led the American League in hitting with a .369 batting average; he had 44 doubles and 103 RBIs. Fonseca even stole a career-best 19 bases that year, a heady number for a notoriously slow runner. After the season he was named as the Most Valuable Player of the American League by the Baseball Writers Association of America.7

The following January, Fonseca became ill with scarlet fever and was ordered to bed-rest for several weeks. He missed much of 1930 spring training, entered the season weakened and out of shape, and then injured his wrist. Fonseca had only 129 at-bats that year with a .279 batting average; his inability to stay healthy was again being noticed. When Fonseca started 1931 with a hot .370 average in his first 26 games, the Indians wasted no time in trading him to the Chicago White Sox for dependable third baseman Willie Kamm. The White Sox moved Fonseca to the outfield; there, in 121 games, he hit .299, accumulating a .312 batting average in 573 at-bats for the season. His efforts, however, did little to help the Sox, who finished eighth.

After the season White Sox manager Donie Bush resigned, and on October 12, 1931, owner Charles Comiskey named Fonseca to succeed Bush; the deal was for two years.8 Fonseca continued to be listed on the active roster, but his playing time diminished greatly.9

The congratulatory messages on Fonseca’s promotion were muted. The White Sox were a franchise in crisis. They weren’t a young team, and their ho-hum pitching staff was the oldest in the league.10 They had 31-year-old Ted Lyons and rookie Luke Appling, both future Hall of Famers, but not much else. They had not had a winning season in five years or a first-division finish in 11 years — and Fonseca was unable to change the trend. His 1932 White Sox were 49-102, setting franchise records for the fewest wins, lowest winning percentage, and lowest attendance. Amazingly, the Sox moved up a notch from the year before to finish seventh. J. Louis Comiskey gave Fonseca the go-ahead to deal for better talent that winter. Fonseca made a slew of trades that winter, and with Philadelphia’s Connie Mack holding one of his periodic fire sales, Fonseca picked up future Hall of Famer Al Simmons, third baseman Jimmy Dykes, and outfielder Mule Haas for $150,000.The reinforcements, along with Appling’s development, allowed the White Sox to improve by 18 wins and a rise to sixth place in 1933.

But Fonseca’s movie camera, to that point only a hobby, became an important element in the manager’s thoughts in 1933. Fonseca was intrigued by aspects of the game that the human eye couldn’t process — but that perhaps the camera could. Simmons, for instance, appeared to put his left foot in the bucket (move it away from the ball as he swung), but the camera showed the foot striding into the ball at contact. Fonseca began taking slow-motion and stop-action film of the stars of the game, dissecting swings and throws, how the body coordinated its parts into successful action. He began filming his players in the spring, using the results to tutor them out of their various ineffective tendencies. At the start of league play, the effect of this practice seemed positive, as the White Sox were 19-14 and in third place near the end of May. However, the team’s record began to erode by midsummer; they slipped below .500 in late July with a nine-game losing streak, finishing the season sixth with a 67-83 record. Perhaps Fonseca and his camera’s candid eye had become too demanding for his players and their modest aspirations.11 Nonetheless, Fonseca had become a zealot; that winter, in San Francisco, he was showing schoolboy audiences the film he shot, demonstrating the right and wrong way to do things on the field.12

The following season, on May 8, the White Sox had a 4-11 record, and were in a five-game losing streak. Lou Comiskey woke up the following morning and decided that Fonseca was no longer his man.13 He called Jimmy Dykes to his room and immediately appointed him as his new player-manager. Dykes went to the ballpark, where it became apparent that Fonseca had not been informed of the change; Dykes didn’t have the heart to break the news. So Fonseca, in his unofficial final game as manager, led the team to an 8-1 win over the Senators.14

Fonseca put his freedom and the money he had saved to good use. He filmed a variety of action throughout the American League, creating images of the game’s top players and the techniques that made them successful. He wrote to all of the American League owners, explaining how film could be used as both a promotional and educational tool. He showed up at the American League office in August with the 45-minute film he had shot and edited, and asked AL President Will Harridge to hire him as a promoter for the league. Harridge gave Fonseca three months and $500 to prove himself; Fonseca became a one-man show, lugging camera and screen to more than 100 venues so that 40,000 attendees had seen his presentation by December. He also managed to get to the World Series during that time span, shooting footage to add to another film for the following year. His work was rewarded by Harridge, who signed Fonseca to a one-year contract for 1935.

That December Fonseca presented the film Play Ball; his career was established. Harridge created the position of American League promotional director for Fonseca, and installed him in his own office on Michigan Avenue in Chicago.15 Fonseca was to shoot a film or two every year, see that it was made available to the public, and to also act as an ambassador of the AL, often accompanying the film with personal appearances to schools and civic clubs, offering anecdotes along with hitting and fielding tips for the youngsters in his audience. The films were premiered each winter at a dinner attended by the game’s dignitaries. Fonseca was the producer, director, scriptwriter, and sometimes narrator. Film titles included The First Century of Baseball (1938), Touching All Bases (1940), Batting Around the American League (1940), and The Ninth Inning (1941). The films often concentrated on specific skills like pitching, baserunning, even umpiring. Fonseca had produced 12 films for the American League by the end of 1946.16

The films and their presentations were not Fonseca’s only educational activities. He made appearances as an instructor at offseason amateur baseball camps, wrote the book How to Pitch Baseball for youngsters, and produced baseball instructional material for General Mills to use in marketing Wheaties. His audiovisual résumé expanded as he broadcast Chicago Cubs games in 1939 and 1940 for WJJD in Chicago with Charlie Grimm as his sidekick.17Always thinking of ways to use his camera, Fonseca devised an experiment to gauge the speed of Bob Feller’s fastball.18

When the United States entered World War II, another opportunity developed for Fonseca to expand his career. President Roosevelt had insisted that major-league baseball continue operations as a means of sustaining American spirit and giving hard-working citizens both entertainment and a degree of normalcy. Weren’t the American military entitled to the same support? Fonseca approached Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis with the concept of producing a World Series film to be distributed to armed-forces bases throughout the world. Landis agreed; equipment manufacturers Hillerich & Bradsby and A.G. Spalding & Bros. agreed to sponsor the film’s production and distribution.

The 1943 World Series was a good opportunity for Fonseca to get some experience as a producer without embarrassing himself. The Yankees won the Series in five games; there were no unusual plays or controversial calls that the camera might have missed or caught. And The 1943 Baseball Classic: The World Series was geared toward the patriotism of the war effort, so a substantial amount of footage dealt with nongame subject matter. The 23-minute film began with such elements as the singing of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” (complete with lyrics and bouncing ball), Babe Ruth reading a script extolling the virtue of baseball as a bedrock of American culture, and shots of various baseball dignitaries in the stands. Announcer Bob Elson did not have any game action to describe until the seventh minute of presentation. Much of the action showed batters swinging and baserunners circling the bases; the ball was rarely in view once it left the infield. But other than brief snippets of film from movie-house newsreels, it was the only view that the soldiers — and many fans — had; it was wonderful.

Both in New York and St. Louis, Fonseca was limited to cameras on the first-base side. A lower camera shot the infield play, much of it focused on the baserunners between home and first or second. A higher camera would try to catch plays at the plate or the outfield. Hard-hit balls were difficult to view once beyond the infield, and had only Elson’s reporting to make them exciting. But in the following years, more cameras were added, the sight lines became more refined, and the live ball was kept in view. The shadows in the late afternoon played havoc with the visibility, but the image was on camera. Fonseca was able to capture more of the spectacular, unusual, or important plays.19 The fans not only knew what happened by reading about it; they really knew what happened by seeing it themselves. When a ball eluded Hank Greenberg in the 1945 World Series, he was charged with an error. The official scorer later reversed the call, and Fonseca’s film confirmed to the viewer that the ball had taken a strange hop, high over Greenberg’s shoulder.

World War II had ended by the following season and, with the troops back home, it seemed pointless to some to keep up the Series films. Why would fans have much interest in watching games that had been decided two months earlier? Fonseca lobbied Commissioner Happy Chandler and the major leagues for continuation, and won. The National League threw in its support and the Major Leagues Motion Picture Division was formed with Fonseca in charge. Fonseca would continue to produce and direct the World Series film each year, and would also produce a film of the annual All-Star Game. He would also continue to produce films on the history of the game along with educational films about baseball technique.

But the fans soon became jaded, expecting the cameras to capture every nuance on the field. In the 1948 World Series between the Indians and Braves, when Fonseca missed filming a pickoff tag by Lou Boudreau on the Braves’ Phil Masi — who then went on to score the game’s only run — skeptics opined that Fonseca “lost” the evidence that would prove that umpire Bill Stewart had made a bad call, that the National League had pressured him to do so. Regardless of what the camera showed, it was not prudent for the narrator to comment on the umpiring.20 In the 1955 World Series, there were two attempted steals of home during the first game. Billy Martin was called out, while Jackie Robinson was safe; the cameras distinctly showed the opposite. Fonseca, who was the narrator, never uttered a peep despite the stop-action evidence.

In 1958 Fonseca made a proposal to American League President Will Harridge that caused a stir throughout baseball. Fonseca thought the game would be improved if the substitution rule was relaxed: that a player could exit a game — due to temporary injury or strategy — then re-enter the game at another time. Fonseca had nothing to gain; his affiliation with the game was nonpartisan. But he could see that older players — especially sluggers like Ted Williams — could be more than once-a-game pinch-hitters. The idea presaged today’s designated-hitter rule, but in 1958 there were few backers. Baseball leaders like Casey Stengel and Frank Lane ridiculed the idea.21

In August of 1959, Fonseca’s motion picture dynasty began to change. For 15 years he had been the baseball movie czar, taking the support of Spalding and Hillerich & Bradsby to use as he saw fit. But now the giant Coca-Cola Company was to be the sole sponsor and producer of the films. The supervision of the films remained with Fonseca, but the control was starting to slip. That fall Vin Scully narrated the first World Series film in color, with the Coca-Cola distribution network delivering the film to the public, worldwide.

Other factors were making inroads into Fonseca’s domain. By 1960 a high percentage of American households now had a television set to watch the nationally aired World Series. Videotape made the programs immediately available to those who had missed the live airing. Primitive instant replay made controversial or unusual plays immediately available for review during the games, eliminating the need to wait two months for Fonseca’s editing process to be completed. Fonseca’s work had gone from marquee status to rain-delay fodder. Fonseca remained true to himself through 1968, working hard to create revealing films without disrespecting the efforts of players, managers, and umpires, but taking more and more flak from critics who remarked on his reluctance to avoid film commentary on debatable umpire calls. In 1969 Dick Winik became the producer of the World Series films. Fonseca was given credit as a technical adviser for two years, and then his involvement completely ended. Fonseca had retired from filmmaking with 60 movies in the can, but he hadn’t retired from baseball.

The Chicago Cubs admired Fonseca’s eagle-eyed ability to dissect what was happening on the field, and hired him as a batting instructor for their major-league players at the beginning of the 1970 season; the Cincinnati Reds soon followed suit, giving Fonseca the distinction of working for rival teams simultaneously. For the next nine years, Fonseca instructed hitting stars like Johnny Bench, Rick Monday, Billy Williams, Bill Madlock, and any hitter on any team who asked for advice.22 He was straightforward and succinct. More than anything, he advised his students to have patience, to wait until the last possible instant before attacking the ball.

Lew Fonseca finally retired from his beloved game at age 80, after 60 years of service to the major leagues. He died on November 27, 1989, at 90, in Ely, Iowa. He was survived by his son, Lewis Jr.; his daughter, Carolyn Rusoff; and three grandchildren.

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

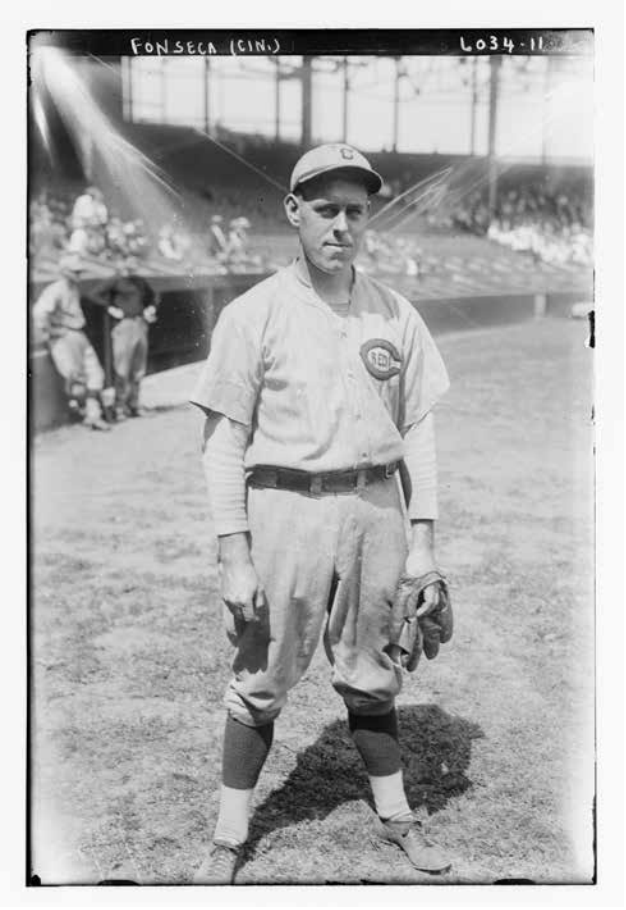

Photo Caption

Multi-talented Lew Fonseca: major leaguer; film directorproducer; “baseball educator.”

Sources and Acknowledgments

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I also used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for player, team, box-score, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this biography. I obtained information from The Sporting News through PaperofRecord.com and also used the archives.chicagotribune.com, GenealogyBank.com, and NewspaperArchive.com websites. I consulted The Official Major League Baseball World Series Film Collection (MLB Publishing/A&E Home Entertainment, 2009). Finally, I greatly appreciate the assistance of Jenifer Fonseca of Beaverton, Oregon, Lew’s granddaughter, who provided me with family and background information.

Notes

1 The Park Bums were a San Francisco semipro tradition with many famous alumni including Fonseca, O’Doul, Willie Kamm, Harry Heilmann, Jimmy Caveny, and George Kelly. The Sporting News, January 19, 1933: 7.

2 St. Mary’s had the reputation as a place where “they raise ball players in the oven.” Paul J. Zingg, Journal of Sports History Vol. 17, Spring 1990. (Hooper, a Deadball Era outfielder with the Boston Red Sox and then the White Sox, was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1971.)

3 Fonseca’s injuries over his playing career include the following: four broken shoulders, a fractured wrist, a chipped ankle bone, a dislocated hip, a concussion, a broken arm, and a severed artery in his leg. Russell Schneider, The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC., 2004), 168.

4 This billing appeared as an advertisement for the Palace Theater in Cincinnati. Cincinnati Post, February 24, 1922. A Fonseca profile printed a decade later noted that Fonseca was holding out in 1923 in Cincinnati, and that Reds owner Garry Herrmann, upon hearing him sing at Keith’s Vaudeville Theater, gave him a $1,000 raise. “Leaves From a Fan’s Scrapbook,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1933: 7.

5Slide, Kelly, Slide was a baseball comedy produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer starring William Haines and Sally O’Neil, directed by Edward Sedgwick. New York Yankees Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri were part of the cast, along with umpire Beans Reardon. TCM.com.

6 Fonseca spent his winters at his home in California focusing on whatever interest captivated him at the time; his activities were always good for a line or two in the hot-stove editions of The Sporting News.

7 Fonseca overcame very formidable competition in the American League of 1929. Sixteen batters in the league that year batted at least the 450 times necessary to qualify for the batting title, and were to become Hall of Famers; that year, Fonseca outperformed them all.

8 Charles Comiskey died two weeks later, on October 26, to be succeeded by his son, J. Louis Comiskey; J. Louis was referred to amicably as Lou or J. Lou by the press. Throughout his life, Fonseca took pride in the trust the senior Comiskey had showed in hiring him. The Sporting News, January 3, 1962: 19.

9 Fonseca had intended to return to his regular outfield post for 1932, but his injured ankle kept bothering him; over 1932 and 1933, he managed 17 hits in 105 plate appearances, then took himself off the roster.

10 Donie Bush explained his resignation: “I don’t mind losing ball games if there is a prospect of better days ahead, but I feel that whatever reputation I possess as a manager would be jeopardized by remaining another year.” John Snyder, White Sox Journal (Cincinnati: Cleresy Press, 2009), 187.

11 With all of the trades the White Sox had made in 1932-1933, the team’s average age became two years older (29.7), only five years younger than Fonseca and unfamiliar with his ways. It’s difficult to imagine a group of grizzled veterans taking lessons from an exuberant but inexperienced manager. Fonseca, with his personality and style, would more likely have succeeded at the college level.

12 The Sporting News, December 21, 1933: 2, refers to Fonseca as “the ambassador of the American League, spreading the gospel of the game throughout the country.”

13 J. Louis Comiskey: “I had no intention of letting him go two days ago. I made up my mind on that while watching yesterday’s ballgame.” International News Service, Hammond (Indiana) Times, May 9, 1934: 9.

14 Dykes: “Hell, I wasn’t going to tell him. All I know is that on my first day as manager of the White Sox, Lew Fonseca managed the team.” Fred Stein, And the Skipper Bats Cleanup (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 205.

15 Fonseca had a counterpart in the National League, another former ballplayer, Ethan Allen. Over time, Fonseca did most of his teaching through film, whereas Allen was more a writer of books. Bernard Crowley, “Ethan Allen,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org.

16 The Sporting News, December 25, 1946: 10.

17 A hilarious combination, Fonseca and Grimm would get the official attendance one-half inning before it was announced. They would then “predict” the number to the radio audience, just a few off from the announcement that was about to come. Tiring of the ruse, they decided to “predict” the exact number one day, then told their fans they were no longer going to do it because it had become “too easy.” John C. Skipper, The Cubs Win the Pennant!: Charlie Grimm, the Billy Goat Curse and the 1945 World Series (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 22.

18 Bob Feller: “Radar guns were a generation away, but Lew Fonseca came up with a way not only of testing my speed, but illustrating it in a dramatic exhibition. He wanted it to be man against machine, me against a guy on a motorcycle. I was to throw against a standard shooting target with a bull’s eye, on a hot day in Chicago’s Lincoln Park. The cycle was going 86 mph when the driver blew past me, but the baseball won by three feet. The pitch was calculated at 104 mph.” See Bob Feller and Bill Gilbert, Now Pitching, Bob Feller (Charleston, South Carolina: The Citadel Press, 2002), 111.

19 Observations and descriptions of Fonseca’s World Series films are based on the author’s own viewing of The Official Major League Baseball World Series Film Collection.

20 Fonseca is credited as the “Baseball Supervisor” on the 1949 feature The Kid from Cleveland. For more info, check: “The Kid from Cleveland: A Celebration of the Postwar Cleveland Indians,” by Rob Edelman, in Batting Four Thousand: Baseball in the Western Reserve, ed. Brad Sullivan, a 2008 SABR publication.

21 The Sporting News, August 13, 1958: 1, 4, 10, 12, and August 27, 1958: 14, 43.

22 After 45 years of studying major-league hitters, Fonseca made this comment in 1965: “The only players who ever inquired about what I had learned have been the top stars like Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Ernie Banks, Hank Greenberg and Stan Musial. Never has a .250 hitter consulted me.” The Sporting News, March, 6, 1965: 7.

Full Name

Lewis Albert Fonseca

Born

January 21, 1899 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

November 26, 1989 at Ely, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.