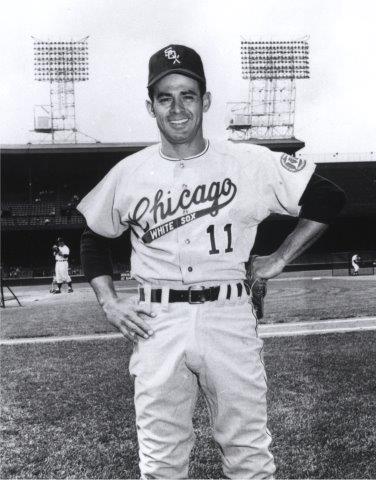

Luis Aparicio

The name Luis Aparicio is closely linked with Venezuela. Both Luis Aparicio Ortega (Ortega) and his son, Luis Aparicio Montiel (Aparicio), had a significant impact on bringing the game of baseball to new heights in Latin America. For that reason, many say that when talking about one, you can’t help but think of the other.

The name Luis Aparicio is closely linked with Venezuela. Both Luis Aparicio Ortega (Ortega) and his son, Luis Aparicio Montiel (Aparicio), had a significant impact on bringing the game of baseball to new heights in Latin America. For that reason, many say that when talking about one, you can’t help but think of the other.

The younger Aparicio was much more than an outstanding baseball player whose endurance, defense, and speed during an 18-year old major-league career earned him a spot in baseball’s Hall of Fame. He was a symbol of the growth and development of the game of baseball in Latin America — specifically in Venezuela and in his hometown of Maracaibo. Aparicio’s place among the greatest players in baseball signified the climax of a cycle of progress for the game of baseball, which has become the national sport of Venezuela and an intrinsic part of its cultural heritage.

To fully understand the significance, impact, and legacy of Aparicio’s career, one needs to take a journey back into the first steps of the game in Maracaibo.

The emergence of baseball in Maracaibo began around the turn of the 20th century when an American businessman, William Phelps (who later became a media mogul and philanthropist), opened the first department store in town, the American Bazaar. While he imported baseball equipment from the United States, he also saw the need for educating local children about the game in order to sell his merchandise. Phelps became a baseball enthusiast and taught schoolkids the rules of the game, which they quickly understood. He served as the first umpire of documented games and built the first baseball field in the coastal city of Maracaibo.

From the sport’s inception around 1912, baseball quickly became a favorite pastime of people of all classes. Several fields were created throughout the small urban area, and both adults and children were fascinated with the sport. In just a few years, the game spread throughout the region and it was soon established as a professional game. People fell in love with the game, and were willing to gather and pay to watch the best players and teams. They called it “the game of the four corners.” The game of baseball had found its stage in the country.

Through the years, the region had a constant flow of American workers from oil companies who helped shape the identity of the city as well as the influence of American culture. Baseball was no exception. By 1926, a heated rivalry between Vuelvan Caras and Santa Marta was catching the attention of followers and local sports media. In fact, the first big hero of local professional baseball was a shortstop from Vuelvan Caras, Rafael “Anguito” Oliver. Early on, the media shone a spotlight on the role of the shortstop.

Oliver became an icon and two brothers were some of his biggest fans — Luis and Ernesto Aparicio Ortega. The Aparicio Ortega brothers (in the Latin American custom, they used their father’s and mother’s surname) were also natural athletes; Luis enjoyed soccer but ended up practicing baseball with Ernesto. Both became quality infielders. Luis, however, became the big star, the super athlete, while Ernesto, who had great playing tools, concentrated on learning the game as a science. He became a successful manager, coach, and team owner, transmitting his knowledge over generations.

Luis gained fame for his great plays and intelligence in the position of shortstop. He became a reference, a master, and a key player sought by many teams throughout the country. He played in both professional leagues in the country, in Caracas and Maracaibo. He became the first player “exported” from Venezuela when he signed with Tigres del Licey of the Dominican Republic in 1934.

Also in 1934, Ortega and his homemaker wife, Herminia Montiel, welcomed their son Luis Ernesto Aparicio Montiel. By the time Aparicio was born in Maracaibo on April 29, his father was shining as one of the first baseball superstars of Venezuela and Latin America. Ortega was an All-Star player and one the most famous players ever of Venezuelan baseball. “An artist in the shortstop position,” many called him.

Uncle Ernesto became a mentor to Luis. In Gavilanes, where his father also played, little Luis got his first job in baseball: batboy. His father and uncle taught him the secrets of the game. He also had the chance to learn from players of all nationalities, including Cuban, Dominican, and American players.

Baseball was his life. Aparicio recalls his mother washing baseball uniforms for his team and talking about baseball all day. From the age of 12, when he played shortstop for a team called La Deportiva, Aparicio displayed the grace and elegance he learned from his father. From then on, Aparicio was a member of several teams in Maracaibo, Caracas, and Barquisimeto. He was constantly moving with his family, depending on the time of year and which team his father was playing for.

That was his life: baseball, the stardom of his father, the knowledge of his uncle and whatever the game brought to the family table.

In 1953, Caracas hosted the Baseball Amateur World Series, and Luis Aparicio, then 19 years old, was selected to represent Venezuela. It was his first big tournament, and he played shortstop, third base, and left field. Although Cuba won the tournament, Aparicio was recognized both in the stands and in newspapers as the most electrifying player, who made great plays and showed security and maturity in all positions. Fans waved white handkerchiefs during this tournament, praising the teenager with great speed and a solid glove. All eyes were on him for the first time, but the name of his famous father would always be on his shoulders if he chose to be a professional player.

Soon after the Amateur World Series, the day arrived. Aparicio had to tell his parents he was quitting school to become a professional baseball player. His mother was not happy with the decision. His father, on the other hand, told him something that would stand out in his mind for the rest of his career. “Son, if you are going to play baseball for a living, you will have to be the number one always,” said his father. “You will never be a number two of anybody, always be the number one.”1

That winter, the best four teams in Venezuela played in the country’s first national tournament. The teams — Gavilanes and Pastora from Maracaibo, and Caracas and Magallanes from Caracas — rotated their games in four cities and it was the first tournament played under the umbrella of major-league baseball.

Aparicio signed with Gavilanes and his debut was scheduled for November 17, 1953, in Maracaibo. That day it rained, and his debut was postponed until the next day, November 18, which is a special holiday in Maracaibo. The city celebrates the day of its lady patron, the Virgin of Chiquinquirá, and festivities are held all around. Among them is the special baseball game between the crosstown rivals Pastora and Gavilanes.

Aparicio’s father, Ortega, who also played for Gavilanes, led off the game against Pastora’s Howie Fox, a major-league veteran. After the first pitch, Ortega went back to the dugout and pointed to his son with his bat, signaling it was time for Luis to take his father’s bat and replace him at home plate for his first official at-bat.

The crowd of 7,000 gave a 15-minute standing ovation to this simple but magical gesture. They were recognizing Ortega — known as “The Great of Maracaibo” — for his outstanding career, his talent as the best shortstop in Venezuelan baseball, for his dedication on the field, and for more than 20 years of contributing to the development of the game in Maracaibo. At the same time, people were showing Luis the huge burden he had on his shoulders for carrying his father’s name, and for the responsibility he had on the field from that moment.

Aparicio Jr., at 19 years old, understood the situation and embraced it with maturity. “I knew the responsibility on me. I knew about the expectations people had everywhere I stepped on a field. I just had to be great as my father, otherwise people would consider me a total deception,” he said in later years. “It was destiny.”2

Panorama, the local newspaper, wrote the next day: “Aparicio´s son’s debut was patronized by the Virgin herself.” For a very Catholic-religious region, this was a big deal.3

Aparicio ended up being named the best shortstop of the tournament. By December, the Cleveland Indians were negotiating with him. Gavilanes manager Red Kress, who was a coach for the Indians, spoke with general manager Hank Greenberg about signing Aparicio, but Greenberg replied that he thought Luis too small to play baseball. Chico Carrasquel, who was playing for Caracas and Chicago at the time, talked to Chicago White Sox general manager Frank Lane and told him about Luis, asking him to sign the youngster before someone else did. Caracas’s manager, Luman Harris, also talked to Lane. Soon after, Lane sent an offer and a contract for Aparicio with a $10,000 check. Young Luis became a member of the White Sox.

Aparicio’s days in the minor leagues were hard. His English was very limited. He knew he belonged in the majors, but the learning process was strict. Carrasquel was the big-league shortstop. After spring training in 1955, Aparicio was sent to Memphis in the Double-A Southern Association. He thought about going back to Venezuela and quitting the White Sox, but both his father and Carrasquel convinced the novice of his potential and explained to him the process of reaching the majors, a road even tougher for Latinos, especially in those years. Carrasquel, who was the big baseball idol in Caracas, became Aparicio’s mentor and a father figure for him. Aparicio also recalls meeting a singer that season in a small bar in Memphis, a young man named Elvis Presley.

Aparicio’s days in the minor leagues were hard. His English was very limited. He knew he belonged in the majors, but the learning process was strict. Carrasquel was the big-league shortstop. After spring training in 1955, Aparicio was sent to Memphis in the Double-A Southern Association. He thought about going back to Venezuela and quitting the White Sox, but both his father and Carrasquel convinced the novice of his potential and explained to him the process of reaching the majors, a road even tougher for Latinos, especially in those years. Carrasquel, who was the big baseball idol in Caracas, became Aparicio’s mentor and a father figure for him. Aparicio also recalls meeting a singer that season in a small bar in Memphis, a young man named Elvis Presley.

In October 1955, the White Sox traded Chico Carrasquel to the Cleveland Indians, leaving the door open for Aparicio. When Lane announced the trade, a Chicago journalist said: “You are trading your All-Star shortstop? You will need a machine to replace Chico.” Lane replied, “Yes, that’s precisely what we have — a machine, and his name is Luis Aparicio.”4

Aparicio was named the American League Rookie of the Year in 1956. He was the first Latin American player to win the award. He finished with a .266 batting average and a league-leading 21 stolen bases, and also led the league in sacrifice hits. The stolen base as a strategy was becoming less and less used in baseball in those years. Aparicio revived the essence of the stolen base from the moment he reached the majors. He injected the White Sox with the game of speed, the Caribbean game, where speed is a key. He was praised for his defense but during his first season had 35 errors.

Luis needed work on his throw. Venezuelan journalist Juan Vené, who covered Aparicio’s entire career, recalled, “Fans were afraid to sit behind first base and they were really aware of the throw every time Aparicio was fielding a grounder because the ball often ended into the stands.”5

His debut met everyone’s expectations at home, but he knew he needed to do more. After his first season, when he returned home with his wife, Sonia, Aparicio said, “By seeing how so many people have gathered to welcome me at the airport just to say hello and congratulations, it makes me realize that I still have a long way to go and a lot of work to do to go beyond their expectations. I need to put the name of my country and my people up high; I feel my game represents them.”6

In 1958, Aparicio won his first Gold Glove, was named to his first All-Star Game, hit .266, and led the league in stolen bases for the third consecutive year, with 29. Chicago ended up in second place for the second year in a row behind the Yankees. The situation in the American League was tough. The Chicago White Sox was an outstanding club but the Yankees were the Yankees, and in those years they simply dominated baseball. There were no playoffs. To go to the World Series they just needed to finish first in the American League. The White Sox needed to reach one more step, and they did it in 1959.

Dámaso Blanco, a former infielder for the San Francisco Giants, remembers 1959: “I went to Chicago in August 1959 with the Venezuelan baseball team for the Pan Am Games and they took us to Comiskey Park to watch the White Sox and Luis Aparicio. It was my first MLB game ever and I was very anxious. Aparicio hit a single on his first at-bat and we all noticed that people started to yell: ‘Go! Go! Go!’ At first we did not understand what was happening and then our guide explained people were actually rooting for Aparicio to steal second base. I can’t really describe how proud we felt listening to a full Comiskey Park rooting for a fellow Venezuelan and the team leader of the ‘Go Go White Sox.’ ”7

That season, the White Sox won 94 games and finally won the pennant. Among the keys to their success were Aparicio’s base-stealing skills and his defense along with his double play partner and close friend, Nellie Fox. For Chicago it was a magical era. It was their first trip to the World Series since 1919. This team was the complete opposite of the Black Sox. It was fun to watch. Aparicio remembers: “We were so close, like a family. We enjoyed our game and the fans of Chicago so much during 1959. Having guys in the team like Ted Kluszewski, Jim Rivera, Sherm Lollar, and Early Wynn was just amazing. We just had to win the league because we were good, having fun in the field, and playing very seriously.”8

Aparicio ended up second to his double-play partner Fox in the voting for the American League’s Most Valuable Player. He stole a career-high 56 bases that year. He realized no one in baseball was better than him at stealing. His speed was a key to victory. He led the team in runs with 98. “Before the season Al Lopez, our manager, told me he wanted me to focus on my base stealing,” Aparicio said long after his career ended. “They wanted me to spice things up in the club and that was going to be our key to win games that season.”9

After their great season, the White Sox lost the World Series to the Dodgers in six games. Aparicio hit .308 (8-for-26), and although he was thrilled to participate in the fall classic, he was deeply frustrated in not winning the Series. “The people were very excited in the city, because they waited 40 years to see their team in a World Series. They were disappointed, but at the same time they treated us like winners,”10 he recalled. This first trip to the Series made Aparicio realize how important it was to be a winner and how hard a team needed to work to win it all.

Hoping to return to the World Series in 1960, the White Sox instead slipped to third place. They fell to fourth place in 1961 and fifth in 1962. The Sox wanted to rebuild their team, and in January of 1963, Aparicio and veteran outfielder Al Smith were traded to the Baltimore Orioles for Ron Hansen, Pete Ward, Dave Nicholson, and Hoyt Wilhelm.

The trade was a jolt to Luis, but he was moving to a contending team built around a foundation of power and pitching. Aparicio added speed to the Baltimore lineup, winning two more stolen base titles in 1963-64 to give him nine consecutive seasons as the American League stolen base champion, an all-time record. More importantly, he helped solidify the Oriole defense. Luis and future Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson formed one of the best shortstop-third base combinations of all time.

In 1966, the Orioles won the American League pennant, and Aparicio once again faced the Dodgers in the World Series. Although his offense was not as solid as it was in 1959, he still contributed with four hits and great defense during the series, which the Orioles swept in four games. It was first and only championship ring of his career. He came back to Maracaibo as a hero, dedicating his part of the title to his parents, who were his biggest supporters.

In November of 1967, Luis was traded back to the White Sox. As a veteran player, he became the team leader and mentor. During his second stint in Chicago, his glove was still his great tool, though his speed was not the same. He worked on his offense and in 1970, at the age of 36, batted a career-high .313.

Before the 1971 season, Aparicio was traded to the Boston Red Sox and played with them for three more seasons. In two of them was he was selected to the All-Star Game. In 1973, at the age of 39, he batted .271 in 132 games and stole 13 bases in 14 attempts.

Vené remembers March 26, 1974: “Luis was in the Red Sox spring camp when he got the notice that he was being released. He wanted to play one more season; he was 40 and still felt he had it. When he went back to the hotel he had a letter from Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. It was an open contract that had a note saying: “You put in the amount to play for the New York Yankees.”

Aparicio sent the envelope back with a note that said: “Dear Mr. Steinbrenner, thank you very much for your offer but I just get released once in my lifetime.”11 That was the end of Aparicio’s playing career. He went back to Maracaibo that day with his family.

From 1956 to 1973, no other shortstop was more dominant in his position than Luis Aparicio, who won nine Gold Gloves. He was a profound influence on the game during his era with his speed, helping to revive the stolen base as an offensive weapon. He was selected to 10 All-Star teams. He played in two World Series and won one, and he set the most significant personal record for himself: No player had played more games at his beloved position in the major leagues than he (2,583). (The record has since been broken by Omar Vizquel.) He finished his career with 2,677 hits, a .262 batting average and 506 stolen bases.

After 10 years of eligibility and a huge crusade by many Hispanic journalists pushing his candidacy for the Hall of Fame, he was elected to the Hall in 1984, becoming the first Venezuelan to ever receive this form of baseball immortality. “This is a triumph of Venezuela for all Venezuelans,” said Aparicio when he heard of his election.12

His biggest regret is that his father didn’t live long enough to see his son elected to the Hall of Fame. Luis Aparicio Ortega died on January 1, 1971. After his death he was honored with his election to the Hall of Fame of Venezuelan Sports. The Maracaibo baseball stadium was officially named Luis Aparicio Ortega “El Grande de Maracaibo.” After the creation of the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, the Aparicio Ortega brothers, Ernesto and Luis, were also inducted.

After retirement, Luis moved back to Venezuela and worked during the Venezuelan league in winter as manager. He managed Caracas, Zulia, Lara, La Guaira, Magallanes, and Cabimas. He was a celebrity and his retirement was not easy for him. They were hard times, not economically because he was very organized financially, but emotionally. He spent more time with his family and was part of many local projects of many kinds.

In the early 1980s he became a television commentator for Radio Caracas Television during the Venezuelan League. In fact, when he got the notice about his selection to Cooperstown, he was working with RCTV. Although he enjoyed it for a while, television was not his passion, but at least something to stay close to the game, if he was not managing.

In the 1990s Luis was back to the field with Tiburones de La Guaira in the winter league as a manager and coach. Aparicio moved to Barquisimeto. He enjoyed spending time with his family and especially his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His family suffered a big setback when his daughter Sharon was the victim of a crime in Venezuela. After this incident, he concentrated even more on his family. He continued to enjoy and follow baseball and kept his participation in baseball and Hall of Fame events with the help of his son Nelson.

After his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Aparicio’s status of celebrity increased greatly. He became known as the most important and influential Venezuelan athlete of all time, the most revered and followed. He also made several trips a year to the US to participate in autograph sessions, fan festivals and former player activities. He was a constant supporter of Hall of Fame gatherings, including All-Star games and Cooperstown induction weekends.

His solid and impeccable image and personality caught the attention of ESPN International and ESPN Deportes who invited him as a special color analyst for the international broadcasts of Venezuelan baseball from 2011 to 2013, alongside veteran and famed Spanish-broadcasters such as Emmy-award winning Ernesto Jerez.

Aparicio has since become an active baseball follower and his voice is present through his social media accounts, where he has provided opinions and personals perspective of issues around baseball. Most notably in 2017 he was invited to participate in a ceremony honoring the Latino members of the Baseball Hall of Fame prior to the 2017 All-Star Game in Miami, Florida. Aparicio respectfully declined the invitation and publicly stated: “Thank you for the honor @mlb, but I cannot celebrate while the young people of my country are dying while fighting for freedom”13

Aparicio did not attend the 2017 Hall of Fame induction for the same reasons and actively became a strong opponent of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro and the regime that has ruled Venezuela since 1998.

Maracaibo still remembers every November 18 as part of the festivities around the Virgin holiday, the anniversary of Luis Aparicio’s debut. At the Aguilas del Zulia game, Aparicio has made the ceremonial first pitch. Every year the Luis Aparicio Award is given to the best Venezuelan player of the major-league baseball season. It was a tribute to his career and to the memory of his father.

In 2006 the Chicago White Sox unveiled the Luis Aparicio statue at the U.S. Cellular Field in the center-field concourse and created by artist Gary Tillery. Aparicio attended the event with Sonia celebrating 52 years of marriage and with his son Luis Jr and daughter Karen. The sculpture is part of a two-player series depicting Aparicio waiting to catch a ball from his longtime double-play partner Nelly Fox, whose widow, Joanne, also attended the ceremony. “This is my biggest moment in baseball. I thank the White Sox organization for giving me the opportunity to play baseball, and I thank God for giving me the ability to play this game. The only thing I can say is baseball is so much of me, I even met my wife playing baseball.”14

The 2014 season of the Venezuelan Winter League was played in honor to the 30th anniversary of Aparicio’s induction to Cooperstown and he was honored at every ballpark of the league and the league reinforced and emphasized the biggest honor ever made to a Venezuelan baseball player: the retirement of his number 11 from every team in the country.

Much more than a great player, Aparicio was recognized as a great human being. Most people knew Luis for his playing feats, but ignored his great heart and family values. During his career the integrity he brought to the game was one of his strongest assets. He gave everything he had to win and help his teams. He played simultaneously for 19 years in Venezuelan baseball, doubling the amount of work year round. As a major-league player he played fewer than 130 games in a season only once.

Maybe his greater value was how he embraced and understood his position and his significance on and off the field for the people of Venezuela, a country filled with social problems that universally celebrates the achievements of its people. He was much more than an icon.

People always expected the best from him, and he gave nothing but the best both as a player and as a human being, working hard enough and using his abilities to be among the greatest players of all time. He had huge shoes to fill under the shadow of his father and he never let this issue pressure him during his life. Luis Aparicio assumed a social responsibility and went beyond expectations.

Aparicio was named the Athlete of the 20th Century in Venezuela. Beyond his recognition for being the best player ever born in the country, his integrity and family values always accompanied him. Moreover, he is the role model for future generations and the “godfather” of the dynasty of Venezuelan shortstops in the history of the major leagues. Panorama published a letter Aparicio sent to his mother in March 1956: “To Herminia de Aparicio, Maracaibo. Dear Mom: You are finally the mother of a big leaguer. Try to figure out what it means to me to become ‘a big leaguer.’ Today I’ve cried alone, when they told me they were sending my luggage to Chicago because I had made the big league team. Tears came out by themselves and I just thought about Dad. Mom, please tell Dad that my debt with him is finally paid. Kisses, your son, Luis.”15

Luis has said: “When my father asked me to be always a number one, I always kept that on my mind. I think I didn’t disappoint him. I wanted him to be proud of me, and I know he definitely was. That’s the achievement of my life.”16

Last revised: January 23, 2018

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Sources

In addition to the sources in the Notes, the author also consulted

Verde, Luis. The History of Baseball in Zulia (Maracaibo: Editorial Maracaibo SRL, 1999).

Perfiles: Luis Aparicio. ESPN International. 2002-2007.

Author interviews with Luis Aparicio, Juan Vené, Dámaso Blanco, Angel Bravo. Luis Verde, Nelson Aparicio, and Rafael Aparicio.

¡A La Carga! Tripleplay Sports Productions, Maracaibo, Venezuela. Various televisión episodes 1998-2002.

www.eljuegoperfecto.com

Notes

1 Author interview with Luis Aparicio, July 2008.

2 Aparicio interview.

3 Diario Panorama (Maracaibo, Venezuela), November 19, 1953.

4 Carlos Cárdenas Lares, Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas (Caracas: Fondo editorial Cárdenas Lares, 1990), 78.

5 Author interview with Juan Vené, Cincinnati, August 2007.

6 Diario Panorama, October 10, 1956.

7 Author interview with Dámaso Blanco, Cincinnati, August 2007.

8 Aparicio interview.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid..

11 Vené interview.

12 Revista IND, Instituto Nacional de Deportes, Caracas, Venezuela. August 1984.

13 Luis Aparicio, via Twitter, July 11, 2017.

14 Scott Merkin, “Aparicio, Fox honored with statues,” MLB.com, July 23, 2006.

15 Diario Panorama, March 2, 1956.

16 Aparicio interview.

Full Name

Luis Ernesto Aparicio Montiel

Born

April 29, 1934 at Maracaibo, Zulia (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.