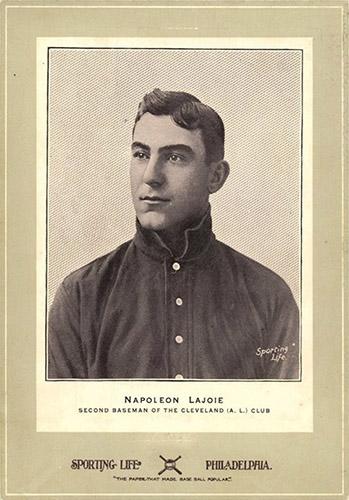

Nap Lajoie

The first superstar in American League history, Napoleon Lajoie combined graceful, effortless fielding with powerful, fearsome hitting to become one of the greatest all-around players of the Deadball Era, and one of the best second basemen of all time. At 6’1″ and 200 pounds, Lajoie possessed an unusually large physique for his time, yet when manning the keystone sack he was wonderfully quick on his feet, threw like chain lightning, and went over the ground like a deer. “Lajoie glides toward the ball,” noted the New York Press, “[and] gathers it in nonchalantly, as if picking fruit….” During his 21-year career, Lajoie led the league in putouts five times, assists three times, double plays five times, and fielding percentage four times.

The first superstar in American League history, Napoleon Lajoie combined graceful, effortless fielding with powerful, fearsome hitting to become one of the greatest all-around players of the Deadball Era, and one of the best second basemen of all time. At 6’1″ and 200 pounds, Lajoie possessed an unusually large physique for his time, yet when manning the keystone sack he was wonderfully quick on his feet, threw like chain lightning, and went over the ground like a deer. “Lajoie glides toward the ball,” noted the New York Press, “[and] gathers it in nonchalantly, as if picking fruit….” During his 21-year career, Lajoie led the league in putouts five times, assists three times, double plays five times, and fielding percentage four times.

But he was even more memorable in the batter’s box, where the right-hander captured four (or five) batting titles, including a modern-era record .426 mark for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1901, won the first Triple Crown in American League history, and finished with a lifetime .338 batting average. An expert bunter who was capable of hitting the ball to all fields, Lajoie was nonetheless completely undisciplined at the plate, regularly swinging at pitches down at his ankles or up at his eyebrows, and occasionally thwarting attempts to intentionally walk him by reaching out for those pitches, too. For years the conventional wisdom among American League pitchers was to try to upset Lajoie’s timing with off-speed stuff, but Francis Richter thought this strategy ineffective, noting that no pitch could fool Lajoie for long. “Good Old Ed Delahanty could clout the horsehide some,” Hugh Duffy once observed, “but [Lajoie] seemed to be just as powerful, if not more so.” Indeed, Lajoie swung so hard and met the ball with such force, that on three separate occasions in 1899 he managed to literally tear the cover off the ball.

Napoleon Lajoie (typically pronounced LAJ-way, though Nap himself is supposed to have preferred the French pronunciation, Lah-ZHWA) was born on September 5, 1874, in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, the youngest of eight surviving children of Jean Baptiste and Celina Guertin Lajoie. The Lajoie clan traced its origins to Auxerres, France, though Jean Baptiste was born in Canada, and emigrated with his family to the United States in 1866, initially settling in Rutland, Vermont before moving to Woonsocket. During Napoleon’s early years, Jean worked as a teamster and a laborer, but his premature death in 1881 forced his children to find employment as soon as they were physically able. After attending school for only eight months, Napoleon was obliged to forsake his formal education in 1885, when he found work as a card-room sweeper in a local textile mill.

About the same time the young lad was seized by the baseball craze sweeping the country. His mother did not approve of his ball playing and so his teammates gave the dark-haired Lajoie the nickname Sandy to hide his presence on the diamond. By 1894 Lajoie was clerking for an auctioneer named C.F. Hixon and playing part time with the semi-pro Woonsockets. As word of his ability spread, Lajoie discovered that other semi-pro teams wanted him to play for them in critical games. He obliged them all and his rate of pay ranged from $2 to $5 per game, plus round-trip carfare. Off the diamond, Nap followed in his father’s footsteps and became a teamster. He drove a hack out of the Consolidated Livery Stable, providing him with the nickname The Slugging Cabby. In 1896 Lajoie joined the Fall River (Massachusetts) club in the Class B New England League, which offered him $500 for the five-month-long season. Lajoie was making $7.50 per week as a cabby and his words of acceptance served as his slogan for his entire career: “I’m out for the stuff.”

Lajoie’s career with Fall River lasted only until August 9, when he and teammate Phil Geier were purchased by the Philadelphia Phillies. With his .429 batting average and .726 slugging percentage, Fall River had no trouble soliciting offers for Lajoie, but Philadelphia was the only franchise that agreed to the asking price of $1,500. During his abbreviated minor league career, Lajoie had played mostly center field, but when he joined the Phillies, manager Billy Nash installed the rookie at first base, which had been manned on an emergency basis by Ed Delahanty. This allowed Del to return to his best position, left field. In 1898 Phils manager George Stallings made several sweeping defensive changes. The most important was shifting Lajoie to second base, where he would achieve his enduring fame. Stallings later explained this move by saying, “He’d have made good no matter where I positioned him.”

Over his final three seasons with Philadelphia, Lajoie matured into one of the game’s best second basemen, using his excellent speed, quick reflexes, and soft hands to adeptly handle all the position’s tasks. “He plays so naturally and so easily it looks like lack of effort,” Connie Mack would later observe. “Larry’s reach is so long and he’s fast as lightning, and to throw to at second base he is ideal. All the catchers who’ve played with him say he is the easiest man to throw to in the game today. High, low, wide – he is sure of everything.” Unlike his contemporaries, Lajoie preferred to break in a new fielding mitt each season, and he also parted from accepted practice by cutting the wrist strap off his glove, providing his large hands with added flexibility and control.

At the plate, Lajoie wasted little time demonstrating that his gaudy minor league numbers had been no fluke. From 1896 to 1900 he never batted lower than .324, and he led the league in slugging percentage in 1897 and doubles and RBI in 1898. He posted a .378 batting average in 1899, though an injury following a collision with Harry Steinfeldt limited him to just 77 games played. It was the first of several seasons in which Nap would miss significant playing time, though the causes of his absences from the starting lineup were rarely typical. In 1900 Lajoie lost five weeks after breaking his thumb in a fistfight with teammate Elmer Flick. Two years later, legal squabbles between the American and National Leagues cut into his playing time, and in 1905, Nap’s leg nearly had to be amputated after the blue dye in his socks poisoned a spike wound. The leg recovered, but the incident led to a new rule requiring teams to use sanitary white socks.

During his career, Lajoie also had some famous run-ins with umpires. In 1904 he was suspended for throwing chewing tobacco into umpire Frank Dwyer‘s eye. After one ejection, Lajoie, who stubbornly refused to leave the bench, had to be escorted from the park by police. And in 1903, Nap became so infuriated by an umpire’s decision to use a blackened ball that he picked up the sphere and threw it over the grandstand, resulting in a forfeit.

But Lajoie’s most famous battle came off the field, when he jumped his contract with the Phillies to join the insurgent American League in 1901. Prior to the 1900 season, Lajoie had been assured by Philadelphia owner John Rogers that he and teammate Ed Delahanty would receive equal pay. After the season began, however, Lajoie discovered that his salary of $2,600 was actually $400 less than Delahanty’s pay. As Lajoie later explained, “I saw the checks.” Incensed, Lajoie exacted his revenge on Rogers in the off-season, when he jumped to Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics of the upstart American League.

When he abandoned the National League in favor of the new organization, Lajoie almost single-handedly legitimatized the AL’s claim to major league status. Rogers, however, immediately moved to block the deal, suing for the return of his “property.” While the case worked its way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, Lajoie, a major star at the peak of his powers, capitalized on the golden opportunity of playing in a newly formed league with a diluted talent pool by putting together one of the most impressive seasons in major league history. Nap punished the American League’s overmatched pitchers in 1901, becoming just the third triple crown winner in baseball history with a .426 batting average (the highest posted by any player in the twentieth century), 14 home runs, and 125 RBI. Lajoie also led the league in hits (232), doubles (48), runs scored (145), on-base percentage (.463), and slugging percentage (.643). Despite those figures, the Athletics could only finish in fourth place.

Ironically, Connie Mack’s team would win the pennant the following year, but they would do so without Lajoie, who moved to the Cleveland franchise after Rogers succeeded in getting an injunction from the Pennsylvania Supreme Court which prevented Nap from playing ball in the state for any team other than the Phillies. Lajoie was able to circumvent the ruling by signing with Cleveland, and skipping all of the club’s games in Philadelphia. (The fact that the A’s never had to face the league’s best hitter in their home park undoubtedly helped them capture the pennant; indeed, the .339 difference between Philadelphia’s home and road winning percentages in 1902 remains the second-highest differential in baseball history.) In the peace agreement brokered between the two leagues following the 1902 season, Rogers dropped his claim on Lajoie, and Nap remained with Cleveland through the 1914 season. During his 13 years with the club, Lajoie became such a powerful symbol of the franchise that the press soon took to calling the team the Naps, thus making Lajoie the only active player in baseball history to have his team named after him.

With his legal status secured, in 1903 and 1904 Lajoie solidified his reputation as the league’s best hitter, winning his third and fourth consecutive batting titles. In 1904 he batted .376, led the league in on-base percentage (.413), slugging percentage (.552), hits (208), and RBI (102). Despite that performance, and despite the considerable offensive contributions of teammates Bill Bradley and Elmer Flick, the Naps finished a disappointing fourth, and in September manager Bill Armour tendered his resignation. After the end of the season, Lajoie formally accepted the position as field manager.

Though he would finish his managerial career with a .550 winning percentage, Lajoie was not a successful manager. When he assumed control of the team in late 1904, Lajoie inherited one of the league’s most talented rosters. In addition to himself, the Naps featured several promising players under the age of 30: Bradley, Flick, shortstop Terry Turner, and center fielder Harry Bay. Their pitching rotation was anchored by a trio of young pitchers, none of whom were older than 25: Addie Joss, Earl Moore (who had won 52 games in his first three seasons), and Bob Rhoads, who would post a record of 38-19 for the Naps in 1905 and 1906.

Despite this assortment of talent, under Lajoie’s leadership the Naps only twice challenged for the American League pennant, losing out to the White Sox by five games in 1906 and the Detroit Tigers by .004 in 1908. Lajoie blamed himself for the team’s second-place finish in 1908, as he batted just .289 for the season and failed in the clutch in two critical games down the stretch. In fact, there is much evidence to suggest that Lajoie’s managerial responsibilities detracted from his on-field performance. After winning four consecutive batting titles from 1901 to 1904, Lajoie put together only one comparable season during his managerial career, posting a .355 batting average in 1906. In both 1907 and 1908, Lajoie failed to clear the .300 barrier.

As manager, Lajoie was criticized for his rudimentary method of relaying signals to the outfielders. He had a way of wiggling his finger behind his back as notice to his outfield when his pitcher was going to throw a fastball, and wiggling two fingers for a curve. Enemy pitchers in the bullpen often could read Nap’s signals, and they were never a mystery to Connie Mack. One contemporary observed of Lajoie, “The great player-artist rather disdained the subtleties of the game and responsibility sat heavily upon him. He failed to lift up lesser players to the batting and fielding heights that he had attained so easily. He knew how to do a thing, but to impart to another how it should be done eluded him.”

Midway through the 1909 season, with the team once again languishing in the standings, Lajoie resigned as manager. Free to once again focus exclusively on his on-field performance, Nap batted over .300 every year from 1909 to 1913. From 1910 to 1912 he batted better than .360 every season, with his .384 mark in 1910 finishing second–or first, depending on your point of view–in the American League batting race.

In one of the most famous episodes of the Deadball Era, Lajoie and Ty Cobb entered the closing days of the season neck-and-neck for the American League batting crown, with the winner set to receive a brand new Chalmers automobile, one of the finest makes of the day in a time when automobiles were still rare commodities. On the season’s final day, the Naps faced the St. Louis Browns in a doubleheader, with Lajoie trailing Cobb and needing a base hit in virtually every at-bat to secure the batting crown. The Browns manager, Jack O’Connor, no fan of the ill-tempered Georgia Peach, ordered rookie third baseman Red Corriden to play deep, well behind the bag throughout both games. Seizing the opportunity, Lajoie dropped seven straight bunts down the third base line for hits, though an eighth bunt was recorded as a sacrifice. His eighth and final hit was a triple belted over the center fielder’s head. O’Connor was fired for his actions, and Lajoie received a congratulatory telegram from eight of Cobb’s teammates, but one week later American League president Ban Johnson declared Cobb the batting title winner, by a margin of .000860. (Subsequent research would determine that Cobb had been erroneously credited with two extra hits, and when this clerical error was corrected, Cobb’s average dropped to .383, giving Lajoie the higher batting average. Nonetheless, in 1981 Commissioner Bowie Kuhn rejected an appeal to declare Lajoie the true 1910 batting champion.) The Chalmers company reacted to the controversy by giving both players free automobiles, but according to Lajoie’s nephew, Nap “didn’t want to accept it,” though his wife insisted that he do so. “He just thought that he, not Cobb, had won that championship and was angry that Cobb had been ruled the winner.”

In 1914 Lajoie struggled to a .258 batting average, as bad eyesight gradually diminished his effectiveness. Following the 1914 season, Lajoie’s contract was purchased by the Philadelphia Athletics, and Nap was reunited with his old friend and manager, Connie Mack. Unfortunately, Nap arrived one year too late to get his first shot at winning a pennant. In 1915 and 1916, Lajoie played out the string as Eddie Collins‘s replacement at second base, posting batting averages of .280 and .246, respectively, while the A’s plummeted into the American League cellar. Following Philadelphia’s dismal 36-117 performance in 1916, Lajoie announced his retirement from the majors. On January 15, 1917, he signed as playing manager of the International League’s Toronto Maple Leafs. Toronto won the pennant and Lajoie captured the batting title with a resounding .380 mark. The following year he signed as player-manager for Indianapolis of the American Association, batting .282 and leading the Indians to a third-place finish in the war-shortened campaign. One month away from his 44th birthday, Lajoie offered his services to his draft board. They declined, with thanks.

Lajoie had married the former Myrtle I. Smith, a divorcée, on October 11, 1906. They purchased a small farm of about twenty acres in the Cleveland suburb of South Euclid and this remained their residence until they moved to a smaller home in Mentor, Ohio in 1939. Long popular in Cleveland, Lajoie was put up as the Republican candidate for sheriff of Cuyahoga County. Failing election, he was named commissioner of the old Ohio and Pennsylvania League. He also dabbled around in a rubber company, sold truck tires, and finally set up a small brass manufacturing company. These businesses were merely diversions to occupy his time. Lajoie had been careful with his money and he and Myrtle lived a comfortable life.

In 1943 the Lajoies made a permanent move to Florida and finally settled in the Daytona Beach area. Myrtle passed away of cancer in 1954. Nap died on February 7, 1959, of pneumonia. The couple had no children.

An updated version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. It originally appeared “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Napoleon Lajoie

Born

September 5, 1874 at Woonsocket, RI (USA)

Died

February 7, 1959 at Daytona Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.