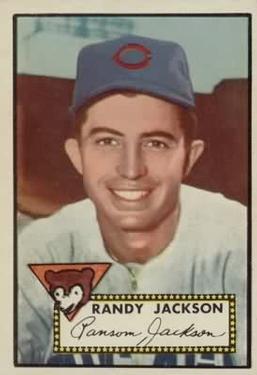

Randy Jackson

Although Ransom “Randy” Jackson later suggested with tongue somewhat in cheek that he went into professional baseball “for lack of anything better to do; I had to earn money somehow,”1 he in fact had options in 1947 when he caught the attention of the Chicago Cubs. Set to graduate from the University of Texas, he had an ensign’s commission in the United States Navy by way of the World War II V-12 officer program. But rather than stay in the active Navy, he elected the Naval Reserve, finished up a degree at Texas,2 and was enjoying himself playing semipro baseball in east Texas when the Chicago Cubs offered him a tryout trip to Wrigley Field in September 1947 that changed his life.

Although Ransom “Randy” Jackson later suggested with tongue somewhat in cheek that he went into professional baseball “for lack of anything better to do; I had to earn money somehow,”1 he in fact had options in 1947 when he caught the attention of the Chicago Cubs. Set to graduate from the University of Texas, he had an ensign’s commission in the United States Navy by way of the World War II V-12 officer program. But rather than stay in the active Navy, he elected the Naval Reserve, finished up a degree at Texas,2 and was enjoying himself playing semipro baseball in east Texas when the Chicago Cubs offered him a tryout trip to Wrigley Field in September 1947 that changed his life.

The Cubs used Russ Meyer to determine how Jackson’s hot collegiate and semipro hitting would stand up against major-league pitching. “The Mad Monk” had been left behind to rest his arm as the Cubs made a late-season road trip, and “Meyer threw fastballs, curves, screwballs, everything except the resin bag,” Jackson recalls in his entertaining 2016 memoir Handsome Ransom Jackson: Accidental Big Leaguer. “It was one of those days everything clicked. Line drives were flying all over the place, a couple out of the park.”3

The tryout success blossomed into a 10-year major-league career that took Jackson from press criticism for perceived lassitude to two National League All-Star teams and hitting cleanup for the defending World Series champion Brooklyn Dodgers in 1956.4 Jackson’s career spanned the 1950s, “a time,” in the words of Jackson’s close friend Loran Smith, associate executive director of the University of Georgia Athletic Association, “we, perhaps, won’t see again. The country was growing and life was better for most Americans, who had emerged from World War II with ‘The Greatest Generation.’ Hope sprang every spring with the crack of the bat. Life, for the most part, was good and baseball was central to the good times.”5 Smith’s words aptly describe the dawn of the decade; Jackson expands the thought and believes the 1950s “changed baseball forever and for the better,” because of full integration by African-American and Latin players, the rumblings of free agency through challenges to the reserve clause, and franchise mobility as a precursor of major-league expansion.6

Ransom Joseph Jackson Jr. was born on February 10, 1926, in Little Rock, Arkansas, the first child of Ransom Joseph Jackson Sr. and Ann Polk Coolidge Jackson. Both were native Arkansans of English and Scottish heritage, Ransom Sr. from Hamburg in the southeast corner of the state, and Ann from the Mississippi River city of Helena in east-central Arkansas. Ann was from a socially prominent family7 and Ransom Sr., a 1922 graduate of Princeton University,8 was a principal in a cotton-brokerage business with offices in New York, London, and Paris.

The brokerage prospered until the 1929 stock market crash. Ransom Sr. then went to work for John Hancock Life Insurance Company and became a top salesman. “This meant my younger sister, Suzanne, and I had it better than a lot of kids during the Great Depression,” Jackson recalls.9

Unlike most players who reach the major leagues, the right-handed-hitting and -throwing Ransom, although a natural athlete, wasn’t a schoolboy athletic phenom. Instead of playing in the local teenage baseball league, he played an informal game called sock-ball within his neighborhood. His high school didn’t have a football program, but he and his friends devised a street game that involved trying to punt a football over each other’s heads. That experience was later to have significant impact on his life.10

Instead of baseball and football, which his school didn’t offer because of wartime restrictions, Ransom applied his athletic skill to golf. His father, an excellent golfer, taught him the game at age 12. His high school did offer golf; Jackson joined the team, then played the game enthusiastically and well for more than 70 years — well into his 80s, when physical ailments finally took him off the course.11 He readily named the Augusta National Golf Club course, which he has played twice, as his all-time favorite.12

Jackson graduated from high school in Little Rock in 1943 and enrolled at the University of Arkansas. But with World War II raging, “it wasn’t long before I had to decide to volunteer for military service or take my chances on being drafted into the army.”13 His father, who headed a flight school at a naval air base in Corpus Christi, Texas, suggested the Navy V-12 officer program. “That’s how I became a student at Texas Christian University,” Jackson recalls.14 There, he happened by football practice one afternoon in 1944; the team was shorthanded and coach Dutch Meyer15 took a look at Jackson’s athletic, 6-foot-1 frame and asked him to join the team.16 Initially reluctant because of his academic responsibilities and because he had never played organized football, he joined the team as a punter and backup halfback. When the first-string punter was injured early in the first game, Jackson’s kicks were instrumental in TCU’s 7-0 win over Kansas.17

Meyer also persuaded Jackson to play baseball at TCU. As the team’s third baseman, “I surprised Coach Meyer and myself by leading the Southwest Conference with a .500 batting average.”18 When Jackson transferred to the University of Texas with the V-12 program in May 1945, he played baseball there for Bibb Falk.19 With the Longhorns, Jackson triplicated his TCU conference batting title, winning his second and third consecutive Southwest Conference crowns in 1946 and 1947.20

Given the opportunity to opt out of the active Navy when World War II ended in 1945, Jackson competed his V-12 commitments at Texas, took a reserve commission, and then graduated with a business degree in 1947.

Attracted by the $400 a month that a semipro team was offering for top collegiate baseball talent that summer, Jackson and several other Southwest Conference players became Conroe (Texas) Wildcats. The team won the 1947 Texas state semipro championship. Jackson’s college exploits had already prompted Cubs scout Jimmy Payton to contact him while he was a student at Texas; when the Wildcats’ season ended Payton quickly arranged the Wrigley Field tryout that ultimately took Jackson to the majors.

“The kid is just a natural athlete,” Payton told Chicago sportswriter Edgar Munzel after the workout. “You just watch. He’ll be at third base for the Cubs by 1949. And it wouldn’t surprise me if he made it next year.”21

It didn’t happen quite that quickly. Although the Cubs signed Jackson to a two-year contract at $6,000 per year on October 9, 1947, and reserved him for their 1948 roster, he needed seasoning at third base. At the end of 1948 spring training, tabbed “the most promising” of six players optioned to the minors, Jackson was assigned to the Class-A Des Moines Bruins of the Western League. There, “Stan Hack, the greatest third baseman the Cubs have ever had,” was embarking on a managerial career after starring for the Cubs from 1932 through 1947. Cubs manager Charlie Grimm was upbeat. “That kid has a great chance to be an outstanding player. He can really hit, he’s fast, and he’s smart. All he needs is some instruction on how to make certain plays around third base. That ought to be a cinch for Stan.”22

Under Hack, Jackson and the Bruins started the 1948 season fast, stalled, then came back strong. Jackson hit an early-season three-run homer in a 5-4 win over Denver,23 and Hack rallied the Bruins to the Western League pennant from 6½ games behind at the end of July. Jackson and Hack warranted a Sporting News photo in the May 26 issue, and the top prospect showed the Cubs they had invested wisely as he hit .322, sixth best in the league.

Jackson lasted well into spring training with the 1949 Cubs before being assigned to the Los Angeles Angels of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. There, he hit well (.318, two home runs) in 14 games but was loaned to Cleveland’s Double-A Oklahoma City affiliate in the Texas League for more seasoning in a slightly less competitive atmosphere. In 138 games at Oklahoma City, Jackson raised his home-run output to 19 and hit .298, warranting postseason praise from new Cubs manager Frankie Frisch, who had replaced Charlie Grimm during the 1949 season. Frisch said in November that his planned youth movement for the 1950 Cubs would include starting Wayne Terwilliger at second base, Preston Ward at first base, Roy Smalley at shortstop, and Bill Serena at third base. “And Ransom Jackson, another rookie, will be ready to step in if Serena doesn’t cut it.”24

Serena, two years older than Jackson, had hit .216 in 44 plate appearances in a September 1949 call-up with the Cubs, but Jackson held his own in 1950 spring training, made the roster, and debuted as a major leaguer in the Cubs’ sixth game of the season on May 2 against Philadelphia at Wrigley Field. Batting sixth, he popped out to first base in the first inning as the Cubs sent eight men to the plate. He got to bat again in the second inning and this time singled to knock the Phillies’ Ken Heintzelman out of the game. Philadelphia had also hit Chicago starter Bob Rush freely, closing the gap to 7-6, when Jackson, batting against Milo Candini with Andy Pafko on second base in the bottom of the sixth, doubled Pafko home, collecting his first major-league run batted in and providing a useful insurance run.25

Grimm gave Jackson eight more starts through the end of May, and he electrified Cubs fans with his first major-league home run on May 5 — a 10th-inning blast as a late-innings substitute that beat the Dodgers 7-6 — but the rookie’s lofty first-game .400 batting average had sunk to .150 by May 27. With Serena playing steadily but not spectacularly,26 the Cubs sought help for Jackson and sent him to Triple-A Springfield (Massachusetts) in the International League, where he was reunited with Hack. It was exactly what Jackson needed; he hit .315 with 20 home runs for Hack, got additional tutoring at third base, and was recalled to the Cubs in September. He replaced Serena on September 12, hit a two-run homer as the Cubs won at Boston, then started the remaining 16 games of the season, hitting safely in 12 of them27 and raising his season average to a more respectable .225. He would never see the minor leagues again.28

Jackson begins his memoir with “They called me Handsome Ransom.”29 Although he did have dark, chiseled, movie-star good looks throughout his career, he suspects the nickname likely arose from a sportswriter’s imagination. Jackson doesn’t mention it in the memoir, but the sportswriter was probably Sec Taylor of the Des Moines Register, who used the term in his April 25, 1948, story reporting the three-run homer Jackson hit against Denver on April 24 in his third professional game, pacing a 5-4 Des Moines win.30 As Jackson advanced to and through the majors, the nickname was in general use around the National League, even by Chicago Tribune feature writer Sally Joy Brown, whose “Sally Club” periodically treated boys and girls “who assure me, by letter, that they are baseball fans beyond question of a doubt,” to Cubs games during Jackson’s tenure in the Windy City.31

Despite Jackson’s strong finish the prior season, Serena started the 1951 Cubs’ opener and the next six games before Jackson got his first start on April 27. On May 6 in Philadelphia, though, Serena broke his wrist sliding into second base. He was initially expected to miss five weeks, but the injury ended his season after 13 games.32 Jackson took over for the rest of the season and turned in a stellar year for the moribund, eighth-place Cubs, hitting .275 with 16 home runs, 76 RBI, 14 stolen bases, and fewer strikeouts (44) than walks (47). He was also the most active third baseman in the National League, leading in putouts, assists, and total chances, but also tied for most errors. His offensive numbers compared favorably with those put up by Willie Mays of the New York Giants, named 1951 NL Rookie of the Year. That Jackson had played 34 games in 1950 and that Mays’s Giants won the 1951 National League pennant after a furious rush to catch and overcome the Dodgers were factors favoring Mays for the award, but Jackson’s fine season was little noticed outside the Cubs front office.33

Phil Cavarretta had replaced Frisch as Cubs manager in the middle of the 1951 season and the team once again pitted Jackson and Serena in a third-base rivalry during 1952 spring training. Jackson got the nod — but he had “turned into a whiz defensively and forthwith stopped hitting.”34 Serena alternated between third base and second base; for the season Serena had 435 plate appearances to Jackson’s 410, and Jackson’s production for the season dropped to a .232 average35 with 9 home runs and 34 RBIs, well off his 1951 totals. In a 1991 interview, Jackson attributed his 1952 travail at least indirectly to Hank Sauer. “I hit behind Hank Sauer all year and he was the Most Valuable Player in the league and I must have been knocked down a hundred times. It was a bad year. They were mad at me and I didn’t do anything.”36

November 1952 brought a happier event. Jackson and the former Ruth Fowler, of Athens, Georgia, a flight attendant he had met on a blind date, were married. They honeymooned in Jamaica and spent the winter in Lawton, Oklahoma, where Jackson ran a laundry and dry-cleaning business with his father.

And he decided to “toss his golf clubs into the attic and concentrate on baseball” in 1953 after analyzing the stark differences between his 1951 and 1952 seasons.37 Jackson had played as much golf as he possibly could during the 1952 season. The decision to forgo in-season golf apparently helped; now 27, Jackson bounced back with a .285/19/66 season in 1953, playing in 139 of the Cubs’ 154 games as the club finished seventh under Cavarretta.

The Cubs brought in Jackson’s mentor Stan Hack to manage in 1954. Reunited with Hack, Jackson had productive years in both 1954 and 1955, achieving the career pinnacle of the National League All-Star team both seasons. Backing up Ray Jablonski of the Cardinals in the 1954 game in Cleveland, Jackson went hitless in two at-bats. But in the 1955 game in Milwaukee, Jackson replaced Eddie Mathews in the top of the seventh inning with the National League trailing 5-0. He lined out against Whitey Ford in the bottom of that inning, but the next inning, with the National League behind 5-2, he singled off Ford to drive in the third NL run. Then when Hank Aaron, the next batter, also singled, scoring Ted Kluszewski, Jackson roared into third base, scoring the tying run when Al Rosen couldn’t handle a throw attempting to nip Jackson. Stan Musial won the game for the National League with a leadoff home run in the bottom of the 12th inning. Jackson rated this All-Star single, RBI, and run scored in a satisfying comeback win as his most thrilling moment in baseball.38

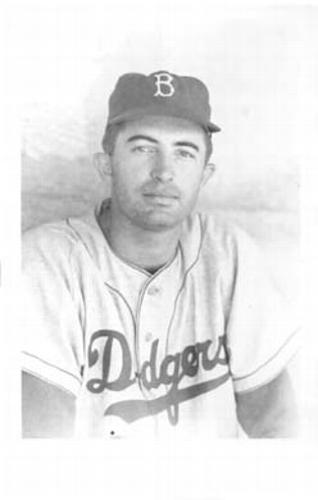

Fresh off their historic triumph over the New York Yankees in the 1955 World Series and with “next year” finally come, the Brooklyn Dodgers needed more solidity at third base than their 1955 tandem of Jackie Robinson, now 37, and Don Hoak could provide. Eyeing Jackson’s solid and steady performance for the hapless Cubs over the prior two seasons, on December 9, 1955, the Dodgers acquired Jackson from Chicago in a trade.39 The press reaction was mainly positive on Jackson’s arrival in Brooklyn, but writer Bill Roeder of the New York World-Telegram and Sun was reserved about the newcomer and his $21,000 contract, observing, “You can never pry a ballplayer away from another club unless the other club is at least slightly dissatisfied.”40 This raised the specter of occasional criticism in the Chicago press that Jackson was lazy — was slow, and lacked hustle and motivation. Jackson, who was thrilled with the trade, having observed the Dodgers for years from the confines of the National League second division, debunked the idea. “I’ve been hearing that for eight years. I do more talking in the infield than anybody. I’m not one of those fire and vinegar boys. My first year in the majors I stole 16 [actually 14] bases, which I think was sixth [actually tied for sixth, behind Sam Jethroe’s 35] in the league. Since then they haven’t let me try 16 times. I just think if you do a good job it doesn’t make any difference how much color you have.”41

There was even speculation in the Brooklyn press that the Dodgers, having acquired Jackson, would part ways with the aging Robinson. Nothing materialized, and after neither Jackson nor Robinson showed a clear advantage in spring training, Robinson opened the season at third base. Except for a start in the second game of a doubleheader on April 29, Jackson rode the bench and pinch-hit until May 29, when manager Walter Alston started him at third base in Pittsburgh. Jackson responded with three hits and from that point took over as the regular Brooklyn third baseman, hitting .308 with 33 RBIs over 43 games through July 8. Jackson then missed 13 games when a porcelain shower knob broke in his right hand and he cut his thumb to the bone.42 Jackson was back as a starter from July 24 through August 30, but his average dropped to .233 during those 34 games. Brooklyn bounced in and out of first place in September with Robinson back at third base as the Dodgers won a repeat pennant — over Milwaukee by a game and Cincinnati by two.

Jackson enjoyed a career highlight during his run as a 1956 Brooklyn starter. On June 29, the Dodgers trailed Philadelphia 5-2 at Ebbets Field heading to the bottom of the ninth. After a walk to Junior Gilliam and Pee Wee Reese’s strikeout, Duke Snider, Jackson — hitting cleanup — and Gil Hodges hit consecutive home runs to win the game.43

Jackson enjoyed a career highlight during his run as a 1956 Brooklyn starter. On June 29, the Dodgers trailed Philadelphia 5-2 at Ebbets Field heading to the bottom of the ninth. After a walk to Junior Gilliam and Pee Wee Reese’s strikeout, Duke Snider, Jackson — hitting cleanup — and Gil Hodges hit consecutive home runs to win the game.43

Jackson had hit a respectable .274 with 8 home runs and 53 RBIs in 101 games for Brooklyn in 1956, but observed most of the World Series, another crosstown Dodgers-Yankees matchup, from the dugout. Brooklyn started fast with wins in the first two games, but then dropped four of five, including Don Larsen’s perfect game in Game Five, to lose the Series. Jackson got into three Series games as a pinch-hitter, striking out in Games Two and Four and flying out against Ford in Game Three. He remembered having conflicting thoughts about whether he wanted to be selected as Alston chose a pinch-hitter for Sal Maglie with two outs in the ninth inning of Larsen’s masterpiece — left-handed hitter Dale Mitchell got the call against righty Larsen — and was rung up on strikes by umpire Babe Pinelli for the historic 27th out.44

Robinson retired after the 1956 season, seemingly clearing the way for Jackson as an unchallenged starter. Despite a poor spring, he opened the 1957 season at third base and started the first eight games before injuring his left knee in a collision at first base in Pittsburgh on April 26. Hitting a miserable .077 in 26 at-bats at that point, he was on the disabled list from May 5 through July 12. Jackson then started through July 27 with a few additional starts thereafter, but during the season the Dodgers used six third basemen.45 Jackson finished the season at .198; he was, though, the last Brooklyn Dodger to hit a home run — a three-run shot off Don Cardwell of the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium in the third inning on September 28. It was only his second home run of 1957, but “it earned me a spot in the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame — a nice consolation prize for a bummer of a season.” Jackson remembers.46

Jackson went to Los Angeles with the Dodgers for 1958 but got into only 35 games before he was waived to the Cleveland Indians on August 4. There, he appeared in 29 games and hit .242. On May 4, 1959, Jackson returned to the Cubs when Cleveland swapped him for pitcher “Riverboat” Bob Smith. “I don’t know who is happier — my wife or me,” Jackson said of the trade.47 He played in 41 games for the 1959 Cubs, backing up veteran third baseman Alvin Dark and occasionally manning left field; he hit his last home run in St. Louis in the second game of a May 10 doubleheader.

In his workmanlike 10-year major-league career Ransom Jackson played in 955 games, collected 835 hits, and batted .261. He had 103 home runs and 415 runs batted in. On October 13, 1959, he announced his baseball retirement from Athens, Georgia, his winter home since he and Ruth had returned there, her hometown, after the 1956 season. He was 33 years old.

Jackson had gone into offseason insurance sales in Chicago in the fall of 1955, just before being traded to Brooklyn. After baseball, he successfully continued that work with Georgia International Life Insurance Company, co-founded the Athens Boys and Girls Club and was the organization’s first president, and played as much top-notch golf as he could fit into his schedule.

As an old Cub, he said in 2017 that he was happy about the team’s 2016 World Series title, but didn’t follow them, the Dodgers, or any other major-league team now — 58 years after his last game.48

In the memoir, Jackson says the lifestyle of baseball puts a lot of pressure on a marriage. “When the crowds stop cheering the stress and uncertainty is different but it doesn’t go away. In 1968 my sixteen-year marriage to Ruth ended in divorce.”49 Jackson had visitation rights with their three children, Ransom III (Randy), Charles Lee, and Ann. Through one of Ann’s friends, he met Terry Yeargan, a high-school teacher and summer tennis pro at the Athens Country Club with two daughters from a prior marriage, Virginia and Meredith. They were married in 1972, combined their families, and had a son, Ransom Baxter, in 1977. Terry went on to earn a doctorate in kinesiology and joined the faculty at the University of Georgia. Retired from teaching but younger than Ransom, Terry was able to assist him as necessary with his declining mobility. She transcribed the 312 pages of legal-pad notes he compiled for the memoir and was instrumental in connecting Jackson with his co-author, Gaylon White.50 In the spring of 2011, a group Ransom called “a family pilgrimage” traveled to Chicago, where he reunited with Ernie Banks and was recognized on the Wrigley Field scoreboard. His 12-year-old grandson, Fowler Bolton, threw out a ceremonial first pitch on April 23; Ransom followed with a second. And the Cubs beat the Dodgers.51 As of 2017 Ransom and Terry lived in Athens, often hosting holiday get-togethers for their children, 13 grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren.

Ransom Jackson, born and raised in Arkansas, educated in Texas, and playing baseball at a time when the civil-rights era had only begun to stir, thoughtfully considers it an honor to have played and become friends with pioneering black ballplayers like Gene Baker, Ernie “Mr. Cub” Banks,52 Sam “Toothpick” Jones, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Orestes “Minnie” Minoso, and especially Jackie Robinson. “It was a thrill to play against Jackie; it was a greater thrill playing with him.”53

He said he had the utmost respect for what Robinson brought to baseball. “I was in college in 1947 when Jackie became the first African-American to play in the big leagues. I was in the minors in 1949 when he won the National League Most Valuable Player Award. I was so absorbed in my own career when I reached the majors in 1950, I had yet to appreciate Jackie’s greatness. He was the ultimate ballplayer, one that transcends all of the statistics used to measure performance. What Jackie did better than anybody else was beat you.”54

Ransom Jackson died at the age of 93 on March 20, 2019, at his home in Athens, Georgia.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Author’s note

This biography arises from my happenstance attendance at an event celebrating the 19th anniversary of the Ty Cobb Museum in Royston, Georgia, on July 29, 2017. Ransom Jackson was one of the speakers for the event’s panel discussion; Loran Smith of the University of Georgia, a legend in documenting the state’s sports history, was the moderator. I enjoyed Jackson’s portion of the panel discussion so much that at the signing session for his memoir, I mentioned the SABR Baseball Biography Project and my surprise that he had not yet been profiled. When I inquired about his interest in participating in a SABR biography, he was enthusiastic. As a result, this biography is more in-depth that it could have been without Ransom’s and his wife Terry’s interest and cooperation, which included a telephone interview on August 16, 2017, and a brief follow-up on October 23, 2017.

Loran Smith provided me with a copy of the Ransom Jackson article he wrote for the 2017 Cotton Bowl program. My SABR colleague Gabriel Schechter once again visited the Baseball Hall of Fame for me.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for box scores, player, team, and season pages, and game-by-game logs. All citations to The Sporting News were accessed through PaperofRecord.com. All newspaper citations that include a page number were accessed through Newspapers.com. Newspaper citations for which no page numbers are included are from copies of clippings from the Ransom Jackson file in the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 “Classic Profile: Ransom Jackson Jr.,” Athens (Georgia) Banner-Herald, onlineathens.com, January 4, 2001, accessed August 6, 2017.

2 Author’s telephone interview with Ransom Jackson, August 16, 2017.

3 Ransom Jackson Jr. and Gaylon H. White, Handsome Ransom Jackson: Accidental Big Leaguer (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), 27.

4 Jackson hit cleanup (Number 4 in the batting order) 37 times for the 1956 Dodgers, delivering 32 of his 53 RBIs.

5 Loran Smith, “The Remarkable Journey of Handsome Ransom Jackson,” Official program. 81st Goodyear Cotton Bowl Classic, 2017: 29.

6 Jackson and White, xxv.

7 The 1923 Coolidge-Jackson wedding warranted a full page of coverage in the Helena newspaper. Jackson and White, 4.

8 Ransom Jackson Sr. played third base at Princeton and had “sufficient talent to get several big league offers when he graduated in 1922.” Complete Baseball, September 1952, excerpted from Ransom Jackson file, Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

9 Jackson and White, 4. Suzanne, born December 7, 1929, was almost four years younger than Ransom Jr.

10 Ransom Jackson remarks at Ty Cobb Museum event, Royston, Georgia, July 29, 2017, attended by author.

11 In late 2017, Jackson was 91 years old and stood 39th on the list of oldest living baseball players. Baseball-Almanac.com, accessed December 18, 2017.

12 Jackson interview.

13 Jackson and White, 14.

14 Ibid.

15 Meyer coached football, baseball, and basketball, handling at least one of the sports at Texas Christian each season from 1923 to 1956, and served as TCU’s athletic director from 1953 through 1963. He was inducted into the National Football Foundation College Football Hall of Fame in 1956. Dutch Meyer entry, footballfoundation.org, accessed August 7, 2017.

16 Jackson recalled that he weighed only 165 pounds when he played football at TCU. He filled out to 180 pounds during his baseball career. Author’s telephone follow-up with Ransom Jackson, October 23, 2017.

17 TCU went on to win the 1944 Southwest Conference title and a trip to the 1945 Cotton Bowl. When the V-12 program was moved to the University of Texas later that year, football coach Dana X. Bible, another future College Football Hall of Fame member, recruited Jackson for his team. Texas won the 1945 Southwest Conference title and played in the 1946 Cotton Bowl. “I became the first and only player in Cotton Bowl history to play in back-to-back bowls for different teams,” Jackson recalls. Jackson and White, 17. One of Jackson’s teammates on the 1946 Texas Cotton Bowl team was quarterback Bobby Layne, who went on to a National Football League Hall of Fame career with the Detroit Lions and Pittsburgh Steelers.

18 Jackson and White, 17.

19 Falk, a career .314 hitter, was an outfielder with the White Sox and Indians from 1920 through 1931.

20 Jackson was named to the University of Texas Athletics Men’s Hall of Honor in 1989. Ransom Jackson entry, texassports.com, accessed August 7, 2017.

21 Edgar Munzel, “Bumper Crop Seen for Cubs,” October 1947. Newspaper and exact date of publication unknown, but probably the Chicago Sun; Cited in Jackson and White, 27.

22 “Hack to Groom Jackson, Cub Third Base Prospect,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1948: 20.

23 The Sporting News, May 5, 1948: 31.

24 Edgar Munzel, “Frisch Kids to Give Cubs Fresh Look,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1949: 13. Serena had also played in the Texas League, with Dallas, in 1949. The Cubs acquired him from Dallas in August 1949.

25 By this point, Jackson was primarily “Randy” to the press and in the box scores, and his player pages at both Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org use that appellation. Although he has always preferred “Ransom,” he says the names were of little concern to him and that “Hey, you” would have been sufficient. Jackson remarks, July 29, 2017; Jackson and White, 160; Jackson interview.

26 Although Serena hit only .239 in 1950, he had 17 home runs and 61 RBIs. His fielding was uneven, as he committed 23 errors at third base, fourth worst in the NL, but his season was enough to garner him minimal support for National League Rookie of the Year.

27 Jackson was 19-for-71 in September 1950 (.268), with seven extra-base hits.

28 In contrast, Serena, with whom Jackson says he had a good relationship despite their competition, hung on with the Cubs through the 1954 season, occasionally playing second base in addition to third base. At the end of the 1954 season the Cubs sent Serena crosstown to the White Sox, but he never appeared in a major-league game for them, He was out of baseball at age 32 after spending the 1955, 1956, and 1957 seasons in the high minors.

29 Jackson and White, 3.

30 Sec Taylor, “Bruins Roll as Leonetti Pitches, 5-4,” Des Moines Register, April 25, 1948: 23.

31 Sally Joy Brown, “100 Sally Fans Will See Cubs Battle Giants,” Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1953: 38.

32 Associated Press, “Serena Breaks Wrist,” (Phoenix) Arizona Republic, May 7, 1951: 21.

33 Brent Kelley, “Handsome Ransom Jackson: the Forgotten Cub,” Sports Collector’s Digest, January 4, 1991: 130; Chicago Cubs press release, March 29, 1952, from Jackson Hall of Fame file.

34 Chicago Daily News, September 3, 1952.

35 Even at .232, Jackson finished with somewhat of a flourish. On July 27 he was hitting an even .200.

36 Kelley, Sports Collector’s Digest. Sauer led the 1952 National League in both home runs (37) and RBIs (121), prompting the knockdowns. For the record, Jackson hit directly behind Sauer through mid-May 1952, but only occasionally after that.

37 James Enright, “Randy Quits Golf, Finds It Hurts His Hitting,” Chicago Herald-American, January 6, 1954.

38 Jackson remarks at Cobb Museum event, July 29, 2017.

39 Jackson and pitcher Don Elston went to Brooklyn; Don Hoak, outfielder Walt Moryn, and pitcher Russ Meyer, used by the Cubs for Jackson’s tryout in 1947 in an earlier 1946-48 stint with the Cubs, went to Chicago.

40 Bill Roeder, “Jackson Deal Seems No Threat at This Point,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, December 15, 1955. This article reports Jackson’s 1956 salary as $23,000. Queried in the interview, Jackson said, “That’s $2,000 I never got!” noting that his top salary with the Cubs was $20,000 in 1955; the Dodgers sent him a contract for the same amount after the trade, but Jackson said he managed to get another $1,000 from Brooklyn general manager Buzzie Bavasi for a $21,000 contract in 1956.

41 Bill Roeder, “Mr. Jackson States His Case,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, February 3, 1956.

42 Jackson follow-up.

43 The late baseball historian and San Francisco State University professor Jules Tygiel, author of the acclaimed Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (Oxford University Press, 1983), noted in a 2006 SABR-L post that he saw this game as a 7-year-old boy. It was his first game at Ebbets Field. SABR-L archives, September 21, 2006.

44 Jackson remarks at Cobb Museum event, July 29, 2017.

45 In addition to Jackson, Bob Kennedy, Gil Hodges, Charlie Neal, Pee Wee Reese, and Don Zimmer all saw time at third base for the 1957 Dodgers.

46 Jackson and White, 126. The Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame induction was April 9, 1996. Jackson follow-up.

47 “Jackson, Wife, Happy He’s a Cub,” Chicago Daily News, May 6, 1959.

48 Jackson interview.

49 Jackson and White, 159.

50 Jackson and White, xix; Jackson remarks at Cobb Museum event, July 29, 2017.

51 Jackson and White, 174-177. The score on April 23, 2011, was Cubs 10, Dodgers 8.

52 Baker and Banks integrated the Cubs in September 1953, Jackson’s fourth season with the club.

53 Jackson and White, 101.

54 Jackson and White, 93-94.

Full Name

Ransom Joseph Jackson

Born

February 10, 1926 at Little Rock, AR (USA)

Died

March 20, 2019 at Athens, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.