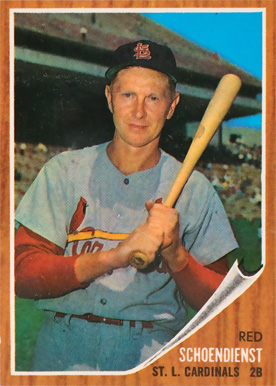

Red Schoendienst

On October 28, 2011, the St. Louis Cardinals won their 11th World Series championship. Among those celebrating with the team was 88-year-old Red Schoendienst, who had first tasted World Series victory as a young second baseman for the Cardinals in 1946.

On October 28, 2011, the St. Louis Cardinals won their 11th World Series championship. Among those celebrating with the team was 88-year-old Red Schoendienst, who had first tasted World Series victory as a young second baseman for the Cardinals in 1946.

Sixty-five years after he savored his first World Series win, Schoendienst was still an integral part of the Cardinals organization. Officially listed as Special Assistant to the General Manager, at heart he was still a coach, donning a uniform for pregame practice at home games, at which he routinely hit fungoes to infielders.

Albert Fred “Red” Schoendienst was born on February 2, 1923, in Germantown, Illinois, a village of about 800 residents 40 miles east of St. Louis. He grew up in a large Catholic family with five brothers and a sister. Three of his brothers would go on to play in the minor leagues.

Schoendienst never saw a major-league game until he played in his first game for the Cardinals in 1945, but the sport was central to his life almost from birth. His father, Joe, had been a catcher in the Clinton County League. By the time his sons were growing up, Joe often came straight from his coal-mining job to umpire a game.

Red’s mother, Mary, a homemaker, made baseballs out of sawdust for her sons and their friends. The balls made it through only a few pitches before they disintegrated. The ingenious young players also used items like corncobs, hickory nuts, and rocks as balls and dried pieces of wood to serve as bats.

St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg (Baseball Hall of Fame J.G. Taylor Spink Award winner in 1979) compared Schoendienst to Mark Twain’s classic character Huckleberry Finn. Never a big fan of school, young Al cared mainly about baseball and fishing – and, in the winter, some hunting. And with all of those brothers and friends, there were always plenty of boys around for a baseball game.

There were two major-league teams in St. Louis while Schoendienst was growing up, and the Germantown boys were split between Browns fans and Cardinals fans. Red favored the Cardinals, but both teams seemed very distant to him. Few games were broadcast on the radio in those days and little was known about their players.

Red preferred playing the game to watching it, anyway. Many of the towns had their own teams in the Clinton County League and the Germantown team’s manager, Ed Roach, helped the young player learn baseball fundamentals. Schoendienst said, “He was always telling us how important it was to think when we were on the field, to know where the base runners were and how many outs there were. He always made certain we knew what inning it was and what the score was.”

By the age of 16, Schoendienst had had enough of school. He got his Social Security card and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s programs to put the country back to work after the Depression. Schoendienst and two friends were assigned to a camp in nearby Greenville, Illinois, where they made a dollar a day planting trees or working on roads or other projects.

Each camp had its own baseball team. Red and his pal Joe Linneman were only 16 and most of the players were in their early 20s, but Red won the position at shortstop and Joe pitched, winning 17 games and losing only one. Both boys had dreams of playing professional ball, but soon Red’s dream would be threatened. He and Joe were building fences one day. Red held the wire tight and Joe hit a staple with his hammer. The staple ricocheted off the post into Red’s left eye. He termed it “the most intense pain I’ve ever felt in my life.” His worst fear was losing the eye and not being able to play baseball. He spent five weeks in a St. Louis hospital. The doctors’ opinion was that the eye would have to be removed. But Schoendienst found one doctor willing to work with him on exercises to save the eye. His vision gradually improved, but continued to be a problem for him.

When World War II broke out, the CCC was disbanded and some of Schoendienst’s brothers went off to fight. Red wanted to play ball as long as he could and took a job at Scott Field (now Scott Air Force Base) in Belleville, Illinois. He heard in 1942 that the Cardinals were holding tryouts and that the prospects could watch a Cardinals game free. That was incentive enough for Red, Joe, and another friend, none of whom had ever seen a major-league game.

The three would-be players hitched a ride into St. Louis. Nearly 400 young men showed up at Sportsman’s Park for the tryouts. Red and Joe passed the first round and were asked to come back the next day. Joe spent the night at his aunt’s house, but Red, too proud to admit he had nowhere to go, didn’t go with him. With a quarter in his pocket, he spent 10 cents on a hot dog at a diner and later, after being driven off a park bench by rain, his last 15 cents for a room in a fleabag hotel – literally. He woke up with bites all over his body.

The Cardinals kept Schoendienst at the camp the rest of that week, but at the end of the week sent him home without offering him a contract. But the Cardinals soon asked him to come back to St. Louis. Their head scout, Joe Mathes, had had to leave town before the camp was finished. When he returned and found Schoendienst unsigned, he rectified that quickly. The Cardinals sent the 19-year-old to their Union City (Tennessee) farm team in the Class D Kitty League. His salary was $75 a month.

Schoendienst gave himself three years to see if he could make a career as a ballplayer. He timed things perfectly, even though he feared that his professional career might end after just one game. He had a good night at the plate, getting four hits. But he made two errors on one key play late in the game. To make things worse, Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey happened to be at the game. Rickey approached his newest hire at his locker and, to Red’s relief, consoled him.

“Young man,” Rickey said, “this is your first time away from home. You signed your first contract, and you played your first game. That would make anybody nervous. You made a couple of errors tonight. You’re a fine ballplayer. But let me tell you something. You’re going to make a few more errors before you get out of this game. You look like you could be a pretty good ballplayer. Go out and get them tomorrow.”

Schoendienst played just six games for Union City. The Kitty League folded in June, as other minor leagues did in that wartime season. The Cardinals sent Schoendienst and his friend Joe Linneman to another Class D team, Albany, Georgia, of the Georgia-Florida League. Because Schoendienst’s injured left eye created problems at the plate against right-handed pitchers, he became a switch-hitter. In the field he made 27 errors in 68 games.

In 1943 the Cardinals moved Schoendienst up to Lynchburg of the Class B Piedmont League. He played mostly at shortstop, but also gained experience at both second base and third base. After just nine games, in which he got 17 hits and batted .472, he was promoted to Rochester, one of the Cardinals’ top two farm teams, where the starting shortstop had been hurt.

Playing for manager Pepper Martin, a veteran of the Cardinals’ Gas House Gang teams of the 1930s, Schoendienst led the International League in hitting with a .337 average. He was the youngest player to lead the league in hitting since Wee Willie Keeler in 1892 (when it was called the Eastern League).

After playing 25 games at Rochester in 1944, Schoendienst was drafted. After basic training, he was sent to Pine Camp, New York, where he hurt his right shoulder while playing for the camp’s baseball team. The recoil from firing weapons aggravated the injury, which would plague Schoendienst throughout his career. Eventually he got a medical discharge because of his eye and shoulder problems. The Cardinals promoted him to the major leagues for 1945, which because so many major leaguers were in the service, was baseball’s worst wartime season. But it was the opportunity of a lifetime for Schoendienst. The Cardinals already had an excellent shortstop in Marty Marion. Schoendienst didn’t mind, however. He didn’t care where they played him, just so they let him play. He started the season in left field, replacing the service-bound Stan Musial, and got his first major-league hit, a triple, on Opening Day. (He also made his first major-league error.) Schoendienst finished his rookie season with a .278 batting average and a league-leading 26 stolen bases.

By the 1946 season the war was over and most of baseball’s stars had returned. Musial reclaimed his position in left field. Marty Marion was still at shortstop. Lou Klein had been expected to be the regular second baseman, but he jumped to the Mexican League in May and Schoendienst took over that position. He played in 128 games at second base, and a few games at shortstop and third base. His place on the team was solidified and he had found the position where he would play for the bulk of his career. He batted .281 that season and started at second base for the National League in the All-Star Game. (It was the first of his ten All-Star Game appearances.) The Cardinals defeated the Dodgers in a playoff for the 1946 NL pennant. Schoendienst then played in his first World Series with the Cardinals defeating the Boston Red Sox in seven games.

Schoendienst was now a seasoned major leaguer, a valued part of the Cardinals, and Musial’s roommate. They became friends off the field, especially after Schoendienst married Mary O’Reilly, whom he had met on a streetcar while going home after a game in 1945. Wed on September 20, 1947, they had three daughters and a son. The son, Kevin, played two years of minor-league ball.

After their 1946 pennant season, the Cardinals finished second in 1947, 1948, and 1949. Schoendienst settled in at second base, continually improving both defensively and as a hitter. Some tips came from his baseball-savvy wife, Mary, who also was able to negotiate better contracts for him.

The most memorable moment in Schoendienst’s ten All-Star Game appearances came in 1950 at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Before the game, he and some other players were kidding around and making predictions on how long a hit they might get. Red pointed to the upper deck in right field and said he was going to hit a ball there. For someone who hit only 84 career home runs, it was a bold statement. But in the top of the 14th inning, Schoendienst came to bat against left-hander Ted Gray. Now that he would bat right-handed, he told his teasing teammates that he’d have to hit the ball into the left-field stands. He did just that – and on the first pitch, providing the winning margin for the National League and laughing all the way around the bases.

Schoendienst reached his peak at the plate in 1953, setting personal highs in batting average (.342), runs (107), home runs (15) and RBIs (79). In early June he was hitting .378, but fell off as the season wore on, and as the season wore on, he battled Brooklyn’s Carl Furillo for the batting title. Furillo broke his hand and missed the last three weeks of the season, leaving his average stuck at.344. A mild slump pushed Schoendienst down to .329. He continued to battle and ended the season with a .342 average, knowing that two more hits somewhere during the season would have made the difference.

Those early-’50s Cardinals teams were not particularly good. Manager Eddie Dyer left after 1950 and there were several managers during the period. Changes in managers and players didn’t seem to make much difference. In 1953 the team was sold to August A. Busch, Jr., the owner of the Anheuser-Busch Brewery, in a deal that prevented the team from moving to another city. After the 1955 season, Busch hired Frank Lane, noted for the frequency of his trades, as general manager. Driving to the ballpark on June 14, 1956, Red heard that he had been traded to the New York Giants. It was part of an eight-player deal that brought Alvin Dark to the Cardinals. Mary had been notified at home and said she “just about fell over” from the shock. Musial called losing his friend to another team his “saddest day in baseball.” The Schoendienst family had just moved into a new home and had no desire to move from St. Louis. Red went to New York alone. In his first game he hit a pinch-hit home run.

In 1957 the family leased a home in New York so they could be together through the season, but they’d hardly had time to settle in when Schoendienst was traded, again in June, this time to the Milwaukee Braves, for outfielder Bobby Thomson, infielder Danny O’Connell, and pitcher Ray Crone. The Braves were a team loaded with talent – Eddie Mathews, Henry Aaron, Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette, Joe Adcock, Del Crandall, Johnny Logan. When Red donned a Braves uniform, Aaron said, “It made us all feel like Superman. We knew he was going to mean so much to our ballclub that wouldn’t show up in the box score. … (H)e definitely became the leader of that ballclub.” Sure enough, the Braves won the pennant, and defeated the Yankees in seven games in the World Series. Schoendienst batted .278 in five games, but had to sit out the last two games with a groin injury. The Braves won the pennant again in 1958, but lost the World Series to the Yankees in seven games.

During that season Schoendienst was concerned about his health. He played in only 106 games and wasn’t hitting well or feeling like himself. After the World Series and the birth of his son, Kevin, he went to the doctor. The examination’s results showed that Schoendienst had tuberculosis and that he had probably been playing with it for years. Red had noticed that his energy would lag in the second half of the season and that a few days off always helped him. Ahead of him now were months of rest at Mount Saint Rose Sanatorium in St. Louis. He determined to do all he could to get healthy and return to the game. By the end of 1958 he had received more than 10,000 letters and cards, including one from President Dwight Eisenhower, who told him that “anyone with the competitive spirit that you have so often demonstrated can lick this thing.”

To speed his recovery, he had surgery to remove part of his lung. The Braves gave him a contract for the 1959 season not knowing whether he would play at all. Schoendienst left the hospital on March 24, 1959, feeling better than he had in years and wondering how much better his career could have been had he been truly healthy throughout it. He didn’t return to action until September, when he got a huge ovation from the 18,000 fans at Milwaukee County Stadium when he came out to pinch-hit. Schoendienst had only three at-bats that season, but he was back in the game and that felt good. He was the honorary chairman of the National Tuberculosis Association’s Christmas Seal campaign that year.

The Braves’ 1960 season started with a new manager. Charlie Dressen had replaced Fred Haney and Schoendienst called Dressen “the only difficult manager I ever played for.” Red had worked out all winter with Musial, Ken Boyer, and other players in St. Louis and was in great shape for spring training. But when the season started, Schoendienst found his playing time cut drastically. Never one to question a manager’s decision, he reluctantly rode the bench. He played in just 68 games, hitting .257. He knew the Braves were trying to ease him out to make way for someone younger, so it came as no surprise when the team released him at the end of the season. But he still wanted to play. Bing Devine, the Cardinals’ general manager, offered Schoendienst a chance to go to spring training in 1961 to try to make the team. Haney, now general manager of the expansion Los Angeles Angels, guaranteed him the Angels’ second-base job. But Schoendienst felt that St. Louis was a better place to raise his family. It was home. He also felt confident enough to feel that he’d get a place on the Cardinals.

He did, of course, make the team and more than 50 years later would still be wearing a Cardinals uniform. He knew his role would be as a utility player and he was fine with that. Sitting on the bench allowed him to learn more about what the manager and coaches did. He played in 72 games in 1961 and hit .300.

As the 1962 season came around, Schoendienst signed a contract to coach rather than play. Part of the reason was that each team had to provide players to the expansion New York and Houston franchises. As a coach he was protected from being sent to one of the new teams. He was put on the active roster when the season started.

Schoendienst enjoyed playing out his career with his friend Stan Musial, who was winding down his Hall of Fame career. Both retired as players after the 1963 season. Schboendienst had signed as a coach for 1963 but was reactivated in late June. His last at-bat was on July 7 in San Francisco. He grounded out, just as he had in his first major-league at-bat 18 years earlier.

Schoendienst’s first full season of coaching, 1964, was an exciting year in Cardinals history. A June 15 trade with the Cubs brought them Lou Brock, who provided a spark that helped take the Cardinals back to the World Series for the first time since 1946. Their opponent was the Yankees, and the Cardinals beat them in seven games. In a surprise move manager Johnny Keane resigned three days after the Series. He had written his resignation letter before the end of the season, after learning that August Busch wanted to bring in Leo Durocher to manage the Cardinals in 1965.

As it turned out, Durocher didn’t get the Cardinals job. Red Schoendienst did. Teams rarely change managers after winning the World Series (although the same thing happened in St. Louis in 2011). Expectations are high after a championship season, making it especially tough on an untested skipper. Some of his veteran players – Ken Boyer, Bill White, Dick Groat, and Curt Simmons – were nearing the end of their careers. The Cardinals finished the 1965 season in seventh place. Still, Gussie Busch believed in Red enough to bring him back for a second season. After a rough start in 1966, St. Louis finished sixth. But they acquired Orlando Cepeda from the Giants and moved into Busch Stadium II during the season.

In 1967 Musial was general manager, Roger Maris was obtained from the Yankees, and Mike Shannon (with Schoendienst’s help in spring training) switched from the outfield to third base. The Cardinals won the pennant by 10½ games). The Boston Red Sox were again trying for their first championship since 1918. Again, they were disappointed as the Cardinals won in seven games, led by Bob Gibson, who won three games, and Brock, who hit .414.

The team stayed essentially the same in 1968 and repeated its trip to the World Series, this time playing the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers took the series in seven games, after St. Louis had a three-games-to-one lead.

Schoendienst continued to manage the Cardinals through the first half of the 1970s, but those teams did not enjoy the same success. After a 90-loss, fifth-place finish in 1976, Red was fired. Not knowing any other business, he knew he wanted to stay in baseball, thinking he might even come back to the Cardinals one day. His next job, though, would be in Oakland.

Charlie Finley had just hired Jack McKeon as the Athletics’ manager. McKeon hired Schoendienst for his coaching staff. It was Red’s first and only foray into the American League. The Athletics were a bad team in 1977, losing 98 games and finishing 38½ games out. McKeon was fired and replaced by Bobby Winkles. Later Winkles was also fired. Schoendienst was offered the job, but had no desire to manage for Finley.

After two years in Oakland, Schoendienst had a chance to go back to the Cardinals in 1979, serving as hitting coach for new manager Ken Boyer, who inherited a team in upheaval. The Cards won 86 games that year, but Gussie Busch wanted more. On June 8, 1980, with the Cardinals in last place, Boyer was fired and Whitey Herzog became the new manager.

Red and Whitey had grown up about 30 minutes apart in southwestern Illinois. They didn’t know each other well, but would work together for the next decade. Busch gave Herzog the added role of general manager so that he could obtain the players he wanted to build the kind of team he wanted to manage. Schoendienst stepped in to manage for the last 37 games of the 1980 season so that Herzog could watch the team and scout the Cardinals’ minor-league teams for prospects. Red returned to his coaching duties in 1981.

Herzog moved players in and out over the 1981 season and by 1982 had the team he wanted. His teams won National League pennants in 1982, 1985, and 1987. They defeated the Milwaukee Brewers in the 1982 World Series but lost to Kansas City in 1985 and Minnesota in 1987.

Schoendienst was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1989. In his induction speech he spoke of the day he and his pals had hitchhiked to St. Louis to try out for the Cardinals, commenting, “I never thought that milk truck ride would eventually lead to Cooperstown and baseball’s highest honor.” He also spoke about his attitude toward playing the game: “I would play any position my manager asked. Whatever it took to win, I was willing to do. All I ever wanted was to be on that lineup card and become a champion.”

Another honor came on May 11, 1996, when the Cardinals retired Red’s number 2. (Technically it wasn’t retired because Schoendienst continued to wear it.)

Mary Schoendienst died on December 11, 1999. She was 76 years old and had loved the game of baseball almost as much as her husband. She was known for reaching out to new players’ wives, helping them adjust to life with a major leaguer. Mary sang the National Anthem before many Cardinals games, and she organized the wives’ charity group, the St. Louis Baseball Pinch Hitters.

Schoendienst stayed involved with the Cardinals throughout Tony LaRussa’s 16-year tenure as manager, there in uniform for most home games. His love of the game never faltered. Nor did the respect and love of fans, players, and managers for him. In his autobiography Schoendienst said, “What makes baseball so great is you can’t hold the ball for 24 seconds and take the last shot or run the clock down and kick a field goal. You have to get 27 outs, one way or the other. Time doesn’t run out until you get that 27th out. Everything I have in my life I owe to baseball. I’ve been lucky in so many ways, making a career out of something I loved to do as a kid. It’s been a great ride, and I’m not ready to end it yet.”

Stan Musial probably summed up his friend best: “A lot of guys had the privilege of playing with or for Red over the years, and I’m proud I was one of them. He is one of the kindest, most decent men I’ve ever known in my life. Even more important than having been his teammate or roommate, however, is having been his friend for so many years. They don’t come any better.”

Schoendienst died at the age of 95 on June 6, 2018.

- Related link: Listen to Red Schoendienst’s SABR Oral History interview with Walter Langford from 1987

An earlier version of this biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Bob Broeg. Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1995)

Jim Hunstein. 1, 2, 6, 9…& Rogers (St. Louis: Stellar Press, 2004)

Red Schoendienst with Rob Rains. Red: A Baseball Life (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 1998)

St. Louis Globe-Democrat

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

www.baseballhall.org (Hall of Fame)

Full Name

Albert Fred Schoendienst

Born

February 2, 1923 at Germantown, IL (USA)

Died

June 6, 2018 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.