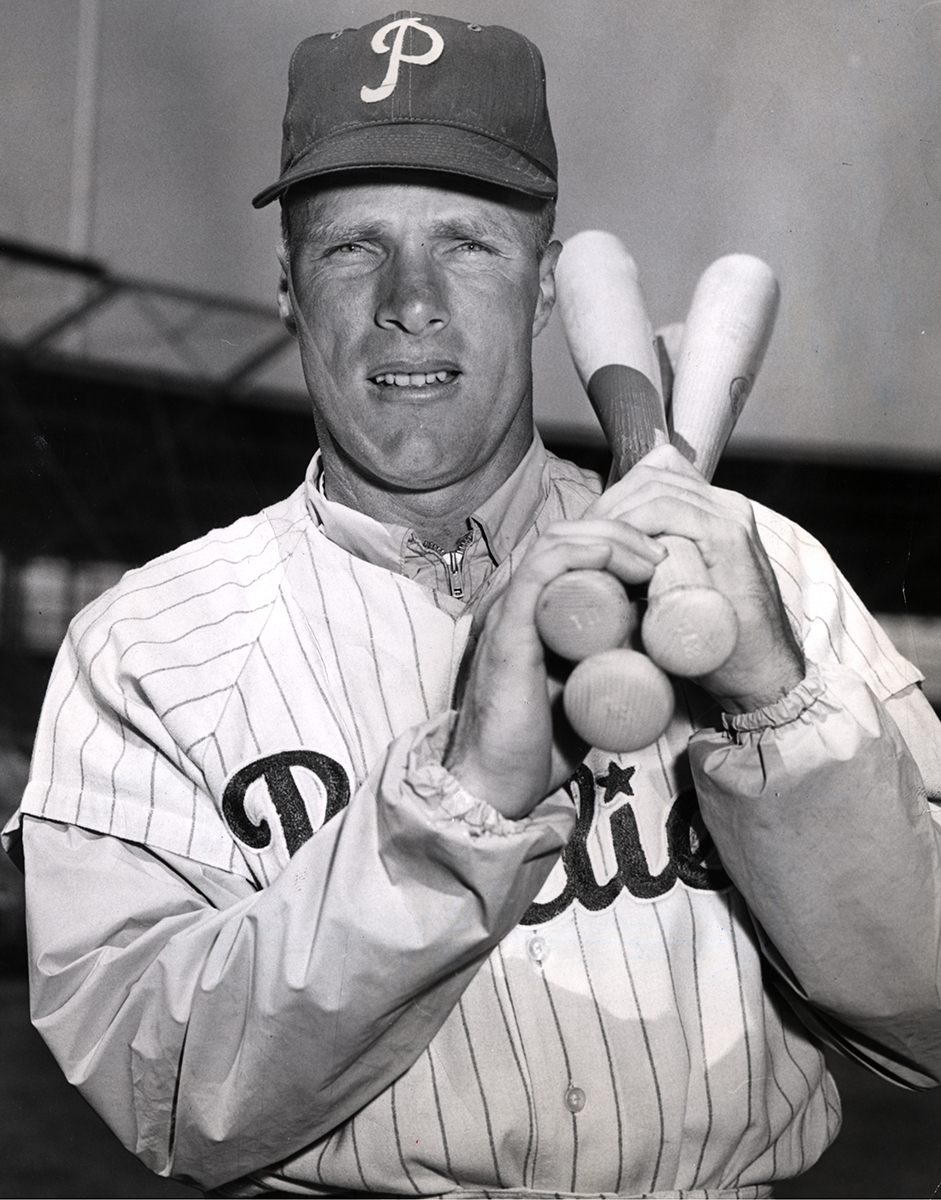

Richie Ashburn

Don Richard “Richie” Ashburn, a Hall of Fame outfielder, who made the most putouts of any outfielder in major-league baseball during the 1950s, started out as a catcher, which should not be surprising because throughout his long career in baseball, Richie Ashburn had always been his own man. His independent quality even emerged during his acceptance speech in Cooperstown. After waiting 28 years for induction, he expressed his opinion about the long wait: “They didn’t exactly carry me in here in a sedan chair with blazing and blaring trumpets.”1

Because of such candor and homespun humor, Ashburn became an iconic figure in fan-gritty Philadelphia during his careers with the Philadelphia Phillies — as a speedy center fielder for 12 years, and as a broadcaster for 34 years. He starred in center field and as a leadoff hitter for 12 seasons, including the pennant-winning Whiz Kids of 1950. Ashburn won two batting titles and earned four All-Star selections. After retiring from the field, he thrilled and amused not only Phillies fans but all baseball fans with his colorful, witty commentary of action on and off the field from 1963 until his sudden death shortly after he broadcast a Phillies-Mets game September 9, 1997.

A son of the Plains, Ashburn came into this world on March 19, 1927, in Tilden, Nebraska, as one of a pair of identical twins, Don and Donna, to his parents Neil and Genevieve “Tootie” Ashburn. Nicknames were common in the Ashburn household: Everyone called the male twin by his middle name, Richie, to further distinguish him from his sister; and Genevieve was called Tootie because of her tiny size at birth.2

Ashburn’s father, Neil, was a blacksmith and monument maker who played semipro baseball on the weekends. His brother Bob said he made more money playing baseball than at his trade. On some occasions the money was just enough to keep his family in food. Neil Ashburn had a very close relationship with his athletically-inclined son — he encouraged Richie in his boyhood activities and steered the boy throughout his developmental years.3

Ashburn tried to play all the sports — except football; his father ruled that out because of the threat of injury, but baseball and basketball were his favorites. He began playing baseball in 1935 as an 8-year-old in the Tilden Midget Baseball League under the tutelage of Hursel O’Banion. He played catcher because his father thought it would be the quickest way to get him to the major leagues, and he batted left-handed because his father said his speed would give him a better jump to first base from the port side.

The term “speed” would always be associated with Ashburn. His high-school basketball teammate Jim Kelly said that Ashburn could dribble down the court faster than the other players could run down it. In his 1948 major-league rookie year, one sportswriter said of the 21-year-old, “He’s no .300 hitter, he hits .100 and runs .200.”4 And even after his playing days ended, Ashburn challenged a young Dick Allen in a foot race and beat him.5

He played baseball and basketball for Tilden High School but the baseball season was short and his coach, Harold Mertz, suggested to Neil Ashburn that his boy needed more playing time. Neil agreed.

Ashburn graduated to American Legion baseball with the Neligh Junior Legion team and continued as a catcher. He was derided at first for his small stature, but he soon drew the admiration of his teammates with his speed and his concentration at the plate. He also played the outfield and it was during this time that Richie’s speed helped him in another way. His coach, Harold Cole, recognized that Ashburn lacked a strong throwing arm. He trained him to compensate for this deficiency by charging balls hit to him and throwing on the run. Ashburn later used this technique in the major leagues.6

It is difficult to imagine the Hall of Fame outfielder continuing on in baseball as a catcher because of his burning speed but, being a good son, Ashburn followed his father’s wish — despite advice to the contrary. As the state of Nebraska’s representative on the West team of Esquire Magazine’s American Legion Junior Baseball East/West All-Star game in 1944 at the Polo Grounds, Ashburn’s quality of play and his size caused Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack to advise him to play another position.7

At his Legion games, baseball scouts quickly recognized Ashburn’s talent and began following him. In fact, he signed three contracts to play professional baseball. He signed first with the Cleveland Indians in 1943 at the age of 16, again in 1944 with the Chicago Cubs to play for their Nashville farm team, and in 1945 with the Phillies. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis voided the Cleveland contract because the rules then prohibited the signing of boys still in high school. He also nullified the Cubs contract because of an illegal clause that would have paid Ashburn if the Nashville franchise was sold while he was playing there. The two nullifications soured Ashburn’s opinion on the integrity of major-league baseball.8

The elder Ashburn shared Richie’s doubts and supported his son’s decision to go to college in 1944 even though 13 of the 16 major-league clubs had showed interest in his son. After one semester at Norfolk Junior College, the Phillies convinced the family that their intentions were honest, and Neil approved Richie’s signing with them. Delighted by this change of mind, Phillies scout Ed Krajnick said, “Something tells me this is about the most important deal I ever made.”9

Ashburn reported to the Utica Blue Sox of the Class A Eastern League in 1945 and it was there that his speed finally changed everyone’s mind about his future position in baseball. He utterly astounded them on one occasion when he beat the batter to first base and took the throw for a putout. His manager, future Whiz Kids pilot Eddie Sawyer, forthwith converted the speedster to a center fielder. According to teammate Putsy Caballero, Richie’s father initially disliked Sawyer’s decision and objected to the new direction. But Neil eventually agreed that Sawyer’s decision appeared right for his fleet-footed son. During his time in Utica the players started calling Ashburn Whitey because of his light blond hair. The new moniker stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Early in the season, Ashburn was drafted by the US Army. Fortunately for Ashburn, the allowed him to finish the season, in which the Blue Sox won the Eastern League pennant while Ashburn led the team in batting with a .312 average. The Blue Sox held a Richie Ashburn Day in August and fans passed the hat and collected $357 for him, an amount he likened then to a million dollars.10

The Army sent Ashburn to Alaska, about which he later quipped: “Sending a ballplayer to Alaska was like sending a dog sledder to the Sahara Desert.”11 He spent a year there and missed the 1946 season.

Ashburn returned to the Blue Sox in 1947, and his team again won the Eastern League championship. Ashburn set a league record for the most hits in a season with 191 in only 137 games. After this successful season he went back to school for a second semester at Norfolk Junior College, where he met his future wife, Herberta “Herbie” Cox.12

Ashburn made the 1948 Phillies team as a 21-year-old rookie and opened the season as the starting left fielder. He replaced veteran Harry “The Hat” Walker, the reigning NL batting champion, as the team’s leadoff hitter. He started the first 12 games in left field before replacing Walker as the regular center fielder.

Ashburn engineered an unusual living arrangement in the Philadelphia suburb of Bala Cynwyd — a home rental with fellow rookies Robin Roberts, Jack Mayo, Curt Simmons, and Charlie Bicknell, a move that saved everyone money, especially when Ashburn’s parents moved in in midseason. On the ballfield, he electrified the crowds at Shibe Park with his hitting, speed, and outfield play.

At the conclusion of a doubleheader with the Cubs in Chicago on June 5, Ashburn sported a .380 batting average and had a 23-game hitting streak. A local sportswriter said, “Richie Ashburn is the hottest thing to hit this town since the great Chicago blaze.”13

Ashburn was the only rookie chosen to the National League All-Star team. In the game held in Sportsman’s Park, St. Louis, won by the American League, 5-2, he hit two singles, garnered the only stolen base in the game, scored one of the NL runs and was named by sportswriters as the outstanding player on the losing side. It was there that Ted Williams bestowed Ashburn with another nickname, “Putt-Putt,” because, as Ashburn explained later, “I ran as if I had an outboard motor in the seat of my pants.”14

Ashburn’s season ended abruptly in August when he broke his finger. He started a total of 101 games in center field and 13 games in left field and finished the season with a .333 batting average. At season’s end The Sporting News named him its Rookie of the Year. In the selection process for Major League Baseball’s Rookie of the Year, he finished third behind Al Dark and Gene Bearden.

Whitey experienced a sophomore slump in 1949, finishing with a .284 average, although he continued to exhibit stellar fielding play, setting a major-league record for outfielders with 514 putouts. Some writers said his sensational catch of a Ralph Kiner liner on September 14 was the greatest catch they’d ever seen at Forbes Field.15

The next season Ashburn returned to the Phillies a married man. He was in top form as the youthful Phillies, known as the Whiz Kids, captured the NL pennant. Richie made a “veteran” adjustment borrowing one of teammate Del Ennis’s heavier bats to fool opposing teams that used a “creeping shift” to thwart the speedster’s infield hits. It worked. He started off at .370, weathered a slump in June, and finished at .303 while leading the National League in triples with 14.

Ashburn’s biggest contribution to the NL champs was a fielding play in the final game of the season, October 1 against the Brooklyn Dodgers in Ebbets Field. The play itself wasn’t extraordinary but its timing was. The Whiz Kids had squandered a six-game lead in first place and faced a tie with the Dodgers if they lost the game. With no outs in the bottom of the ninth inning and the score tied, 1-1, the Dodgers had men on first and second. Duke Snider hit a liner into center field and if the runner on second, Cal Abrams, could score, the Dodgers would force a one-game playoff for the pennant. Ashburn charged the ball, scooped it up, and uncorked a perfect running throw right into catcher Stan Lopata’s mitt in plenty of time to tag Abrams at the plate.

The Phillies won the pennant in the tenth inning when Dick Sisler hit a momentous three-run homer and Robin Roberts retired the Dodgers. Ashburn’s play is considered one of the most significant defensive plays in Phillies history.

Ashburn again led the NL in putouts with 405. He did not perform well in the World Series against the New York Yankees as the Phillies were swept in four games, though the games were close, with three being decided by a single run. He batted only .176 in the Series, 3-for-17, and his disappointment could be summed up with a comment he made as he turned down refreshment after the final game, “I couldn’t swallow a cornflake.”16

The Phillies would not appear in the Series again for many more years as they slid down in the NL standings during the 1950s, but Ashburn’s career did not suffer. He had great years from 1951 through 1954, averaging .318 while leading the NL twice in hits and being named an All-Star in 1951 and 1953. In 1954 he had a career-best 125 walks to lead the league in that category and in on-base percentage with .441.

In 1955 Ashburn received a new $30,000 contract. But before the season began he landed on the disabled list following a collision with Del Ennis that ruined his 731-consecutive-game streak. He recovered relatively quickly — starting in the third game of the season before missing nine games. He pinch-hit in the 13th game, and then resumed playing and went on to have a memorable season — with one exception. For the first time in seven seasons, he failed to lead the league in putouts — but he still posted an outstanding .983 fielding average. His batting excelled — by June he led the NL and had a 17-game hitting streak. He sported a .341 average in July, but incredibly, was not chosen for the NL All-Star team. He shrugged off that slight and finished the season with a .338 average and the NL batting title — his first.

The next three seasons the Phillies continued their slide, never leaving the second division. Ashburn’s play was steady though not stellar with .303 and .297 finishes in 1956 and 1957. The Phillies held a Richie Ashburn Day on August 14, 1956.

In 1958 Ashburn broke out and won his second batting title with a .350 average, edging his center-field rival of the San Francisco Giants, Willie Mays, on the last day of the season with a 3-for-4 effort. He led the league in hits, triples, walks, and on-base percentage. Teammate Robin Roberts remembered that Richie’s first hit that day came on a ball that bounced 50 feet in the air after hitting home plate. Roberts said Ashburn chortled loudly as he safely crossed first base. Richie had told Roberts before the game that for Mays to win the title he needed to get three hits while Whitey went hitless. The chortle erupted because that odd hit practically gave Whitey the title.17

Ashburn’s other accomplishments that year included an unusual double play when he backed up second base on an infield rundown. On June 12 he ran down a Los Angeles Dodgers runner, John Roseboro, who was caught off second base, unaware that Whitey had crept up behind him from center field, for an unusual shortstop-catcher-third base-center fielder double play. And at the end of the season he led the league in putouts, tying Max Carey for the most seasons leading the NL in that statistic. It was only the second time in his career up to that point that he did not finish with double-digit assist totals. Additionally, he served as Nebraska chairman of the American Cancer Society during the offseason.

Ashburn’s 1959 season was largely forgettable. All of his offensive stats fell: hits by 65, walks by 18, stolen bases by 21, and batting average by 84 points. Defensively, it was the same: putouts declined by 136, errors rose to 11, and outfield assists dropped to 4, while his fielding percentage fell 13 points. He suffered through the worst performance of his career.

Richie’s tenure with the Phillies ended when the team traded him to the Chicago Cubs in December 1959. In retrospect, it was a terrible trade for the team as Ashburn rebounded to have three good seasons — two with the Cubs and one with the Mets, although his speed had slowed and his outfield putouts declined all three years. The players the Phillies obtained for Ashburn performed horribly, contributing to their further decline. The Phillies finished last; the third of four straight bottom-of-the-heap finishes from 1958 through 1961. Ashburn’s replacement in center field hit just .237.

Ashburn’s time with the Cubs coincided with their “College of Coaches” experiment — a system of rotating a different coach to manage the Cubs each day, which didn’t work. Some of the coaches were rotated to the minors and back again. A visiting Philly sportswriter asked Ashburn how he was doing: “Not so good,” quipped Richie, “the guy who likes me is in Des Moines.”18

Ashburn’s last season spent as a player spawned a second career in baseball. After playing fairly well on one of the most unforgettable and bumbling teams in baseball history, the 1962 New York Mets (40-120), he sent back his contract offer unsigned — not to get more money, but with the thought that he didn’t want to go through another season like the one he had had with the lowly NL expansion team. His Mets tenure was a horrible season of improbable losses, unbelievable errors, and inept baseball manifested by the quintessential story Yo la tengo.

The story revolved around the antics of the Spanish-speaking shortstop for the Mets, Elio Chacon, and his penchant for frequent near-collisions with outfielders. This was especially true with Ashburn on short fly balls to center field. Ashburn realized that Chacon did not understand the English warning: “I have it,” so he went to a bilingual Mets player and was told that Chacon would understand the warning in Spanish, yo la tengo; that it meant the fly ball was the center fielder’s to catch. Soon enough a short fly ball was hit and a back-pedaling Chacon veered off, following Ashburn’s admonition in Spanish. What was unexpected was that onrushing, English-only left-fielder Frank Thomas completely flattened Ashburn. After pulling his center fielder from the ground, Thomas asked him “What’s a Yellow Tango?”19

Selected as a National League All-Star, he became the Mets’ Most Valuable Player with a batting average of .306. The award merited him the gift of a boat, of which he later said: “…to be voted the MVP on the worst team in the history of baseball is a dubious honor for sure. I was awarded a 24-foot boat equipped with a galley and sleeping facilities for six. After the season had ended, I docked the boat in Ocean City, New Jersey, and it sank.”20

Ashburn also dubbed the much-maligned first baseman for the Mets with his famous moniker, “Marvelous Marv” Throneberry.

He accepted a broadcasting job in 1963 with the Phillies to provide “color” to the regular broadcaster. When asked if he had been making more with the Mets, Ashburn said, “Much more.” And a query as to why he would quit such a good-paying job in a sport he loved and accept a much lower salary elicited a simple, “Well…” 21

Ashburn was not the only candidate for the broadcasting booth. The Phillies first offered it to Robin Roberts, who declined — he played baseball for four more seasons — but who suggested Ashburn to Les Qually, the Phillies official in charge of broadcasting. “The rest is history,” said Roberts.22

It turned out Ashburn had the gift of providing commentary during a broadcast and he parlayed this gift into a career that spanned 35 seasons. His career as a color man enabled his voice and his personality to touch more Phillies fans in the Delaware Valley than all of his on-field heroics at the Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium venue. Folks all over the area listened as he spoke with an infectious zest, corny humor, admirable candor, unflinching disbelief, and an understated outrageousness that endeared him to millions. He spoke his mind and fans loved it along with his wit and humor delivered in his trademark deadpan style. Soon, his aphorisms percolated throughout the Delaware Valley: “This fella on first looks runnerish,” “It’s a leadpipe cinch that they’ll bunt here,” and “Hard to believe, Harry,” among others.

Other, nonverbal, sounds tickled listeners’ ears as well. People recognized Ashburn lighting his pipe when they would hear a match being scratched while on the air. Or they heard him puff his pipe as he piped in with another comment on something odd or good or bad during a game.

Ashburn first teamed with Bill Campbell and By Saam but his true broadcast partner became Harry Kalas when Kalas joined the Phils on-air team in 1971. Kalas gave him another nickname that gave tribute to Ashburn’s unique status with Phillies fans, “His Whiteness.”

The team of Kalas and Ashburn clicked. They complemented each other so well that author Curt Smith said of their rapport and teamwork, “Where chemistry really works … at any time in any franchise was, of course, Harry Kalas and Whitey Ashburn.”23 The pair worked together for 27 seasons and their partnership became noted for Kalas’s smooth delivery of game action and Ashburn’s quips, insights, and critiques.

Besides his broadcasting, Ashburn wrote a regular column for the Philadelphia Bulletin and later for the Philadelphia Daily News. His columns were noted for his candor as well as his insights into sports and baseball.

Ashburn was so well liked that in one of his columns he noted that Cal Abrams — whom he had thrown out at home plate during the 1950 pennant-clincher — paid Richie a compliment: Abrams, wrote Richie, thanked him for throwing him out because that play bestowed more recognition upon Abrams than his short baseball career did. He also noted that Abrams saved all of his baseball cards — including Ashburn’s 1948 rookie card — and, in selling them, was making more money than he did as a player.24

Ashburn stayed married to his wife, Herberta Cox “Herbie” Ashburn, until the day he died. And he stayed true to his roots, returning to his Tilden home every offseason until 1964, when they moved to Gladwyne, a Philadelphia suburb. With Herbie he had six children; he missed every one of their births because all of them were born when he would be with the Phillies. “I was a miserable 0-for-6,” he would quip.25 But he made sure to make it up with them during the offseason and his children referred to him as a good dad.

However, although Whitey’s love for Herbie remained strong, their marriage was not. In 1977, after 28 years of living together, the two separated but did not divorce. The Ashburns lived apart for the rest of their lives but by dint of their unique natures they kept their children together and Whitey remained their father forever.

The Ashburns experienced tragedy when their daughter Jan died in an automobile crash in 1987. It is always a crushing blow when a parent has to bury a child and this loss hurts most. Richie’s grief remained with him and a year later, during a Phillies tribute to Ashburn at the Vet, he thanked the fans for the “thousands of cards and letters” that shared his family’s grief. His column allowed him to make that grief public with Jan’s eulogy in the Philadelphia Daily News of April 28, 1987.

Ashburn’s personality was often described as honest and open. It seemed to allow him to hang out with kings and janitors and everyone in between because he treated everyone the same way. It seems he had the moxie to present himself naturally to anyone, and folks accepted it– and forgave him for it. Stories abound about Richie and this unique quality.

He could be ribald, too. Once, after a lengthy discourse during a game by broadcaster Tim McCarver on the qualities of Mount St. Helen’s volcanic ash, Ashburn opined that “If you’ve seen one piece of ash, you’ve seen them all.”26 On another occasion he admitted that he slept with his bats when he was going good. “In fact, I’ve been in bed with a lot of old bats in my day,” he said.27 And he could be disarmingly charming, often referring to anyone within listening distance as the youngest of men. Once he took leave from some to go into the broadcasting booth, “Well, boys, I can’t be sitting around talking to fans.”28

Richie Ashburn’s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown took some time. In his 15 years of eligibility his vote count did not engender continuation after 1982 and his status was relegated to the Veterans Committee. His candidacy stalled and then ended with the passing of the “60 percent rule” in 1991 that stated eligibility by the Veterans Committee for players whose careers began after 1946 was limited to those who garnered 60 percent of the ballot in previous elections.

Ashburn’s run up to his Hall of Fame induction included two fans who recognized his numbers and took up his banner: SABR member Steve Krevisky and superfan Jim Donahue. Krevisky would appear at every New England SABR gathering and expound on Ashburn’s qualities, especially educating attendees on his defensive statistics but also pointing out that Richie had the most hits of any major leaguer during the 1950s. Donahue organized his campaign around overturning the 60 percent rule, one time forwarding 55,000 postcards to the Hall of Fame. Both men’s efforts paid off and the rule was overturned in 1993. In the spring of 1995 the Veterans Committee voted Whitey into the Hall. The first person Ashburn called was his 91-year-old mother, Tootie, who wept.

The largest crowd in the history of the induction ceremony, more than 15,000 fans, showed up that summer to celebrate not only Ashburn’s induction but that of the greatest third baseman of all time, the Phillies’ Mike Schmidt. Several times during his acceptance speech, Whitey was overcome as he looked out onto a “sea of red clad” Phillies fans.29

It is generally considered that Ashburn’s defensive skills got him in. Although he finished with a .308 average which ranks 120th in major-league history, he hit only 29 home runs, and 82 percent of his hits were singles. However, he led the majors in putouts in nine of the ten years from 1949 through 1958. And he is the only outfielder in major-league history to record four seasons of 500-plus putouts. Despite his “weak” arm, he led NL outfielders in assists three times. Another factor was his durability. He possesses the seventh longest consecutive-game streak in National League history and missed only 20 games from 1948 through 1960.

And his fielding prowess was not limited to the can-of-corn variety. Some of Ashburn’s catches remain as the best in baseball. In addition to the aforementioned Kiner catch, Ashburn’s sensational outfield play at Forbes Field on June 20, 1951, led one famous fan in attendance to wonder. Hall of Famer George Sisler commented, “I’ve been around major-league baseball for 35 years. I’ve seen every great center fielder since [Tris] Speaker. I thought I had seen every sort of impossible catch. But that’s the greatest piece of center fielding I ever saw anywhere by any fielder. I still don’t believe it.”30

Richie’s competitive nature also kept his Hall of Fame candidacy alive. He especially would voice his own self-promotion, since he often mentioned it on air and during off-mike events. And he didn’t hesitate to use his especial candor. “You know, you can also get into the Hall of Fame as a writer or a broadcaster,” Ashburn once said. “I could be the first person in history to miss it in all three categories.”31

Ashburn sometimes kept to himself and he did so on a late summer evening in 1997 after calling a game in New York, telling friend and fellow broadcaster Kalas that he didn’t need any company. Later that night he reached out to a Phillies official, complaining that he didn’t feel well. At 5:30 A.M. on September 9, 1997, Ashburn was found dead in his hotel room.

The city of Philadelphia, Phillies fans, and team officials as well as other major-league teams and their cities descended into collective grief as news of Ashburn’s death percolated across telephone, teletype, audio, and video machines. His wake at Fairmount Park’s Memorial Hall drew thousands and his memorial service generated poignant remembrances as his family and myriad friends in the game sought solace through words, hugs, and tears.

Some years later, his son, Richard, spoke for thousands of us when he said of his father, “To this day some one will tell me a story about him every day. He just blew people away. And he didn’t even know he was doing it.”32

The Phillies have honored the memory of Whitey Ashburn in Citizens Bank Park, their much-admired ballyard off Broad Street in South Philadelphia. There is a long, concession-filled broad walk behind center field dubbed Ashburn Alley where an exciting statue of the former Whiz Kid is prominent. And the TV/radio booth has been named the Richie “Whitey” Ashburn Broadcast Booth. The Phillies also retired his playing number, 1, in 1979, the second number given that honor, and his plaque is featured on the Phillies’ Wall of Fame in Ashburn Alley.

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

http://articles.mcall.com/1995-07-28/sports/3052376_1_richie-ashburn-elmer-flick-consummate-leadoff-man

baseball-reference.com.

http://www.ultimatemets.com/profile.php?PlayerCode=0012&tabno=7

http://www.centerfieldmaz.com/2011/03/original-1962-mets-center-fielder-hall.html

Notes

1 Dan Stephenson, Richie Ashburn, A Baseball Life. DVD. Written and produced by Dan Stephenson, Narrated by Harry Kalas (New York: Arts Alliance America LLC, 2008).

2 Stephenson.

3 Stephenson.

4 Joe Archibald, Richie Ashburn (New York: Julian Messner, Inc., 1960), 47.

5 Stephenson.

6 Archibald, 25.

7 Archibald, 32.

8 Archibald, 29, 30.

9 Archibald, 33, 34.

10 Archibald, 38, 39.

11 Bill Conlin, “Missing Whitey 10-Fold,” Philly.com, September 7, 2007. http://articles.philly.com/2007-09-07/sports/24995587_1_radio-hall-tv.

12 Archibald, 42.

13 Archibald, 46.

14 Archibald, 49.

15 Archibald, 64-65.

16 Archibald, 87.

17 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III. My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), 161.

18 Roberts, 252.

19 http://phillysportshistory.com/2011/05/21/richie-ashburn-is-the-inspiration-for-the-band-name-yo-la-tengo/.

20 http://www.centerfieldmaz.com/2011/03/original-1962-mets-center-fielder-hall.htm”

21 Jimmy Breslin, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game (New York: Viking Press, 1963), 85.

22 Roberts, 252.

23 Stephenson.

24 Philadelphia Daily News, December 9, 1986.

25 Fran Zimniuch. Richie Ashburn Remembered (Chicago: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 83.

26 Zimniuch, 57.

27 Zimniuch, 53.

28 Zimniuch, 61.

29 Stephenson.

30 Frank Yeutter, “They Call Him Mister Putt-Putt,” Baseball Digest, October 1951.

31 Don Bostrom, “Richie Ashburn From Cornfield to Cooperstown,” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), July 28, 1995.

32 Zimniuch, 99.

Full Name

Don Richard Ashburn

Born

March 19, 1927 at Tilden, NE (USA)

Died

September 9, 1997 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.