Roberto Clemente

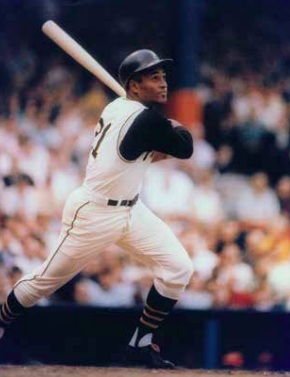

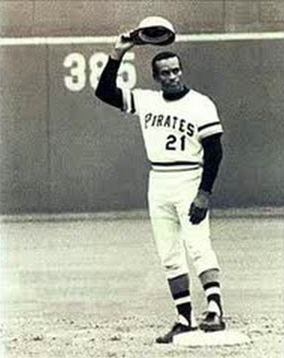

Roberto Clemente’s greatness transcended the diamond. On it, he was electrifying with his penchant for bad-ball hitting, his strong throwing arm from right field, and the way he played with a reckless but controlled abandon. Off it, he was a role model to the people of his homeland and elsewhere. Helping others represented the way Clemente lived. It would also represent the way he died.

Roberto Clemente’s greatness transcended the diamond. On it, he was electrifying with his penchant for bad-ball hitting, his strong throwing arm from right field, and the way he played with a reckless but controlled abandon. Off it, he was a role model to the people of his homeland and elsewhere. Helping others represented the way Clemente lived. It would also represent the way he died.

Jackie Robinson‘s breaking of the color barrier opened the way not just for African Americans in organized baseball but to many others whose skin color had excluded them. By the 1960s Clemente had emerged as one of the best of the players from Latin America.

Clemente came from Puerto Rico, which had established its own baseball history extending back to the late 1800s, at about the same time that the island became a possession of the United States.1 Puerto Rico shares its love of baseball with many of the countries in and along the Caribbean Sea. Professional leagues formed and thrived in the winter in these areas, including Venezuela, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic.

Puerto Rico has produced many great players, such as Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda — because he was black, Perucho never got to play in the major leagues in the United States. His son Orlando did and eventually made the Hall of Fame.

The greatest Puerto Rican player, however, was Roberto Clemente.

Roberto Clemente Walker was born on August 18, 1934, to Melchor Clemente and Luisa Walker de Clemente in Carolina, which is slightly east of the Puerto Rican capital of San Juan. Roberto was the youngest of Luisa’s seven children (three of whom were from a previous marriage).2

Melchor was a foreman overseeing sugar-cane cutters. He also used his truck to help a construction company deliver sand and gravel to building sites. Luisa was a laundress and worked in different jobs to assist the workers at the sugar-cane plantation. Roberto contributed to the family income by helping his dad load shovels into the construction trucks. He also earned money by doing various jobs for neighbors, such as carrying milk to the country store. Roberto used his money to buy a bike and to purchase rubber balls. He liked to squeeze the balls to strengthen his hands.3 Many people commented on the size of young man’s hands. He had strong hands, and it was clear at an early age that he had athletic ability.

Roberto had not just ability but a deep love of sports, especially baseball. He attended games in the winter and watched the star players from the United States mainland. One of his favorites was Monte Irvin. Irvin played for the Newark Eagles in the Negro National League in the summer and for the San Juan Senadores of the Puerto Rican League in the winter. Irvin remembers kids hanging around the stadium. “We’d give them our bags so they could take them in and get in for free,” he said. Irvin didn’t know Clemente was among the kids until Clemente told him years later, when both were in the major leagues. Clemente also told Irvin that he was impressed with his throwing arm. “I had the best arm in Puerto Rico,” said Irvin. “He loved to see me throw. He found that he would practice and learn how to throw like I did.”4 Roberto began playing baseball himself. He wrote in his journal, “I loved the game so much that even though our playing field was muddy and we had many trees on it, I used to play many hours every day. The fences were about 150 feet away from home plate, and I used to hit many homers. One day I hit ten home runs in a game we started about 11 a.m. and finished about 6:30 p.m.”5

When he was 14 years old Roberto joined a softball team organized by Roberto Marín, who became very influential in Clemente’s life. Marín noticed Roberto’s strong throwing arm and began using him at shortstop. He eventually moved him to the outfield. Regardless of the position he played, Roberto was sensational. “His name became known for his long hits to right field, and for his sensational catches,” said Marín. “Everyone had their eyes on him.”6

Roberto also participated in the high jump and javelin throw at Vizcarrondo High School in Carolina.7 It was thought that he might even be good enough to represent Puerto Rico in the Olympics. Throwing the javelin strengthened his arm and helped him in other ways, according to one of his biographers, Bruce Markusen: “The footwork, release, and general dynamics employed in throwing the javelin coincided with the skills needed to throw a baseball properly. The more that Clemente threw the javelin, the better and stronger his throwing from the outfield became.”8

Roberto said that throwing the javelin in high school was only part of the reason he developed a strong arm. “My mother has the same kind of an arm, even today at 74,” in said in a 1964 interview. “She could throw a ball from second base to home plate with something on it. I got my arm from my mother.”9

Although he had great all-around athletic ability, Roberto decided to focus on baseball, even though it meant forgoing any dreams of participating in the Olympics. He began playing for a strong amateur team, the Juncos Mules.

In 1952, Clemente took part in a tryout camp in Puerto Rico that was attended by scout Al Campanis of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Clemente impressed Campanis with his different skills, including his speed. The Dodgers did not sign Clemente then, but Campanis kept him in mind.

Also in 1952, Clemente caught the eye of Pedrín Zorrilla, who owned the Santurce Cangrejeros, or Crabbers, of the Puerto Rican League. The Juncos team was to play the Manatí Athenians in Manatí, where Zorrilla had a house on the beach. Roberto Marín advised Zorrilla to go to the game. Afterward, Zorrilla offered Clemente a contract to play with the Cangrejeros.

Clemente was barely 18 years old when he joined the Cangrejeros. As a young and developing player, he was brought along slowly by the team’s manager, Buzz Clarkson. Clarkson had had an outstanding career in the Negro Leagues in the United States and played many winters in Puerto Rico. Like many great black players, Clarkson’s best years were behind him by the time he got his chance to play in the majors in 1952 at the age of 37. Two other such players were Willard “Ese Hombre” Brown and Bob Thurman, who were top hitters in the Negro Leagues. Both were outfielders (with Thurman also doing some pitching) on the Santurce team that Clemente joined in the winter of 1952-53.

“Clemente looked up to Bob Thurman,” wrote Thomas Van Hyning. “Clemente pinch-hit for Thurman in a key situation and doubled off Caguas’s Roberto Vargas to win the game, earning congratulations from Thurman.”10 Despite the big hit, Clemente did not play much his first winter in the Puerto Rican League.

He began playing more in 1953-54 and even played in the league’s All-Star Game. (The star of the All-Star Game was Henry Aaron of the Caguas Criollos, who had four hits, including two home runs, and drove in five runs.) By midseason, Clemente’s name was appearing along with Aaron’s in the list of the Puerto Rican league leaders in batting average. Clemente finished the season with a .288 batting average, sixth best in the league.

The Brooklyn Dodgers had remembered Clemente from the tryout he had had in front of Al Campanis in 1952.11 Buzzie Bavasi, the Dodgers’ vice president, said that during the 1953-54 season a scout in Puerto Rico told him the Dodgers could sign Clemente.12 Other major-league teams had noticed Clemente, too. One was the New York Giants, the Dodgers’ great rivals. Brooklyn outbid the Giants and Clemente agreed to sign. The Milwaukee Braves also made an offer, one that was reportedly much more than the Dodgers’, but Clemente stuck with his decision.13 He knew that New York City had a large Puerto Rican population and looked forward to playing there.

On February 19, 1954, Clemente signed a contract with the Dodgers, who had to make a decision on what to do with him. The Dodgers had signed him for a reported salary of $5,000 as well as a bonus of $10,000.14 Rules of the time required a team signing a player for a bonus and salary of more than $4,000 to keep him on the major league roster for two years or risk losing him in the offseason draft.15 Many bonus players of this period were kept at the major-league level, pining on the bench for two years rather than developing in the minors. The Dodgers chose to have Clemente spend the 1954 season with the Montreal Royals in the International League, even though it meant they might lose him at the end of the season.

Buzzie Bavasi had the power to determine Clemente’s fate. In 1955, Bavasi told Pittsburgh writer Les Biederman that the Dodgers’ only purpose in signing Clemente was to keep him away from the Giants, even though they knew they would eventually lose him to another team.16 Some writers said an informal quota system was in effect in the early years following the breaking of baseball’s color barrier, but this is not supported by the facts.17 In his biography of Clemente, Kal Wagenheim wrote that the Dodgers would never start all five of their black players in the same game. The box scores prove that is false. (There are other reasons to question the existence of a quota, although it is beyond the realm of this article to fully explore the issue.)18

In a 2005 e-mail message to the author, Bavasi wrote that while there was no quota system, race was the factor in the club’s decision to have Clemente play in Montreal: “The concern had nothing to do with quotas, but the thought was too many minorities might be a problem with the white players. Not so, I said. Winning was the important thing. I agree with the [Dodgers’] board that we should get a player’s opinion and I would be guided by the player’s opinion. The board called in Jackie Robinson. Hell, now I felt great. Jackie was told the problem and after thinking about it awhile, he asked me who would be sent out if Clemente took one of the spots. I said George Shuba. Jackie agreed that Shuba would be the one to go. Then he said Shuba was not among the best players on the club, but he was the most popular. With that he shocked me by saying, and I quote: ‘If I were the GM, I would not bring Clemente to the club and send Shuba or any other white player down. If I did this, I would be setting our program back five years.’”19

So Clemente went to Montreal to play for manager Max Macon. Most accounts say the Dodgers were trying to “hide” Clemente in Montreal by playing him rarely, hoping that other teams wouldn’t notice him and wouldn’t draft him at the end of the season.

Several biographers, among them Phil Musick, Kal Wagenheim, and Bruce Markusen, provide examples to back up the contention that Clemente was hidden. However, a game-by-game check of Montreal’s 1954 season indicates that many of the examples are incorrect.20

Wagenheim and Markusen go so far as to claim that Clemente did not play in the Royals’ final 25 games of the season, another claim that is not correct. In fact, by the final part of the season, Clemente was playing regularly against left-handed starting pitchers.21

Montreal manager Max Macon, until his death in 1989, denied that he was under any orders to restrict Clemente’s playing time. “The only orders I had were to win and draw big crowds,” Macon said.22

It is true that Clemente, after an initial period when he was being platooned over the first 13 games of the season, played little over the first three months of the season. This was hardly unusual for a 19-year-old in his first season of organized baseball.

Also, for much of the year, the Royals had a full crop of reliable outfielders in Dick Whitman, Gino Cimoli, and Jack Cassini. In addition, the Dodgers sent Sandy Amoros down to Montreal early in the season, and Amoros hit well enough for the Royals that he was recalled by Brooklyn in July. The crowded outfield situation didn’t leave a lot of playing time for a newcomer like Clemente. He was often used as a late-inning defensive replacement for Cassini.

When he did play, he struggled. In early July his batting average was barely over .200. Part of that may be attributed to his infrequent playing time; it’s hard for a batter to get in a groove and hit well when he doesn’t play regularly. On the other hand, it’s hard for a player to get regular playing time if he’s not hitting well.

Macon said he didn’t use Clemente much because he “swung wildly,” especially at pitches that were outside of the strike zone: “If you had been in Montreal that year, you wouldn’t have believed how ridiculous some pitchers made him look.”23 Clemente got more chances against left-handed pitchers. Macon was known for platooning, and Clemente often split time in the lineup with Whitman, a left-handed hitter.

Through June and July Clemente often went long stretches without seeing any action. Then, on July 25, he entered the first game of a doubleheader against the Havana Sugar Kings in the ninth inning. The game was tied and went into extra innings. With one out in the last of the 10th, Clemente hit a home run to win it for the Royals.

Macon rewarded him by starting him in the second game of the doubleheader, Clemente’s first start in nearly three weeks. For the rest of the season Clemente started every game in which the opposition started a left-handed pitcher. He had a few more highlights during this time. Near the end of July, he came to bat in the top of the ninth inning of a scoreless game in Toronto. Clemente doubled and went on to score to put Montreal ahead. The Royals won the game, 2-0.

The next time the Royals were in Toronto, three weeks later, Clemente helped them win in a different way. Montreal had an 8-7 lead over the Maple Leafs in the bottom of the ninth. Toronto had a chance to tie the score, but Clemente threw out a runner at home plate to end the game.

Late in August he had two triples and a single at Richmond, although the Royals still lost the game. A week later he hit a home run to win the game for Montreal and give the Royals a sweep of a doubleheader against Syracuse.

Teammate Jack Cassini said, “You knew he was going to play in the big leagues. He had a great arm and he could run.”24 When Clemente began playing regularly against left-handers, the Royals rose in the standings and finished in second place. Clemente batted .257 in 87 games in his only season in the minors.

By the end of the 1954 season, it had become clear to Bavasi and the rest of the Brooklyn organization that other teams were interested in Clemente. However, Bavasi said he still wasn’t ready to give up. The Pirates, by having the worst record in the majors in 1954, had the first pick in the November draft. If Bavasi could get the Pirates to draft a different player off the Montreal roster, Clemente would remain with the Dodgers organization. Each minor-league team could lose only one player.

Bavasi said he went to Branch Rickey, who had run the Dodgers before going to Pittsburgh. After Bavasi declined Rickey’s offer to join him in Pittsburgh, Bavasi said, Rickey told him that, “Should I need help at anytime, all I had to do was pick up the phone.” Bavasi said he used this offer to get Rickey to agree draft a different player, pitcher John Rutherford, off the Royals’ roster. However, Bavasi was dismayed to learn two days later that the deal was off and that the Pirates were going to draft Clemente. “It seemed that [Dodgers owner] Walter O’Malley and Mr. Rickey got in another argument and it seems Walter called Mr. Rickey every name in the book,” explained Bavasi. “Thus, we lost Roberto.”25

When he was drafted by Pittsburgh, Clemente was in Puerto Rico playing for the Santurce Cangrejeros and on his way to his best-ever winter season. He again played with Bob Thurman, but the Santurce outfield had a new addition in 1954-55. It was Willie Mays, who had just led the New York Giants to the World Series championship and was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. An outfield of Clemente, Mays, and Thurman ranks as one of the best ever in the Puerto Rican League. By mid-season Santurce manager Herman Franks was calling Clemente “the best player in the league, except for Willie Mays.”26

Clemente and Mays had been providing some real highlights. In late November, the Cangrejeros were behind by a run going into the ninth inning of a game against Caguas-Guyama. Clemente led off the ninth with a single, and Mays then hit a two-run homer to give Santurce a 7-6 win. Not long after that, the pair starred in another 7-6 win. Mays hit two home runs and Clemente one home run in an 11-inning win over Mayaguez.

Both players homered in the league’s All-Star Game on December 12, leading their North team to a 7-5 win. By this time, Mays, Clemente, and Thurman were the top three players in the league in batting average, and Santurce moved into first place.27

While things were going well on the baseball diamond, there were other problems for Clemente. On New Year’s Eve of 1954, one of his brothers, Luis, died of a brain tumor. Shortly before that, Clemente had been in a car accident that damaged some of his spinal discs. The back injury hampered him for the rest of his baseball career.28

Back on the field, Santurce finished first in the Puerto Rican League. The top three teams advanced to the playoffs, so the Cangrejeros had to win another series to capture the league title. They did that, defeating Caguas-Guayama four games to one. Clemente had four hits, including two doubles, and drove in four runs in the first game of the series, which Santurce won. Caguas-Guayama won the next game, but the Cangrejeros then won three in a row to finish the series. As champions of the Puerto Rican League, they advanced to the Caribbean Series.

The Caribbean Series was played in Caracas, Venezuela, in February of 1955. In addition to Santurce, teams from Cuba, Panama, and Venezuela participated. It was a double round-robin tournament. The team with the best record at the end would be the champion.

The Cangrejeros won their first two games and then faced Magallanes of Venezuela. The game went into extra innings. Clemente singled to open the last of the 11th inning, and Mays followed with a home run to win the game, 4-2.

One more win would clinch at least a tie for the title for Santurce. The Cangrejeros’ fourth game was a rematch against Almendares of Cuba, a team they had defeated in their first game. Almendares opened up a 5-0 lead, but Santurce battled back to win. Clemente drove in two runs to help in the comeback.

Santurce played Carta Vieja of Panama with a chance for the championship. Clemente had a triple as the Cangrejeros scored three times in the top of the first. In the third, Clemente had another triple as Santurce scored four runs to take a 7-0 lead. Santurce won the game, 11-3, to wrap up the championship.

It was the second Caribbean Series title for Santurce in three years. Clemente had been a part of the team that had won the championship in 1953, but he did not play in the series. This time he was a key member of the team that won. Santurce shortstop Don Zimmer, who was voted the Most Valuable Player of the Caribbean Series, said, “It might have been the best winter club ever assembled.”29

Soon afterward, Clemente was in training camp with the Pittsburgh Pirates, hoping to earn a spot in the major leagues. The Pirates had been keeping an eye on Clemente over the winter. Rickey said, “He can run, throw, and hit. He needs much polishing, though, because he is a rough diamond.”30

The Pirates were loaded with outfielders when they began spring training in Florida in March of 1955. Clemente would have plenty of competition for a spot on the team. After the first week of training camp, Clemente earned some good words from Pirates manager Fred Haney. “The boy has the tools, there’s no doubt about that. And he takes to instruction readily. Certainly, I have been pleased with what I have seen,” Haney said. “He has some faults, which were expected, but let’s wait and see.”31

Clemente’s chances were helped when Frank Thomas, the Pirates’ best outfielder, held out for more money and missed the first part of spring training. Thomas then got sick and missed more time. Clemente took advantage of this opportunity and made the team.32

Clemente’s original number with the Pirates was 13, but early in the season he switched to 21, a number that became strongly associated with him. It is reported that Clemente chose the number because his full name, Roberto Clemente Walker, has 21 letters.33

Clemente didn’t play in the first three regular season games. However, he was in the starting lineup, playing right field, for the first game of a doubleheader on Sunday, April 17, 1955, against the Brooklyn Dodgers at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Clemente came to the plate with two out in the bottom of the first inning for his first at-bat in the major leagues. He hit a ground ball toward the shortstop, Pee Wee Reese. Reese got his glove on the grounder, but he couldn’t field it cleanly. Clemente had his first hit. He followed that by scoring his first run to give Pittsburgh a 1-0 lead. However, Brooklyn came back to win the game.

Clemente started the second game of the doubleheader, this time in center field and batting leadoff. He had a double, but the Pirates were unable to score and trailed the Dodgers, 3-0, going into the last of the eighth. Clemente got another hit, a single, as part of a two-run rally that closed the gap, but the Pirates still lost.

In Pittsburgh’s next game, in New York against the Giants, Clemente hit an inside-the-park homer, but the Pirates lost again. At this point, their won-lost record was 0-6. Pittsburgh lost two more games before winning its first of the season. The Pirates went on to finish in last place in the National League for the fourth year in a row. However, Branch Rickey insisted that young players such as Clemente would help turn the team around.

Early in the 1955 season, the new players were leading the Pirates’ offense. Clemente was leading the team in batting average over the first three weeks. On the base paths he was even more exciting. “When he starts moving around the bases he draws the ‘Ohs’ and ‘Ahs’ of the folks in the ball park,” wrote Jack Hernon in The Sporting News.

Hernon added, “The fleet Puerto Rican was a stickout in the field.”34 Forbes Field, the home of the Pirates, was a classic ball park that had opened in 1909. The outfield fence was a brick wall. It was only 300 feet from home plate to the wall down the right-field line. But the wall jutted out and changed directions. Clemente learned the angles and how to play balls that caromed off the fence. He could corral long hits quickly and, with his great arm, opposing baserunners were careful on trying to take an extra base.

Less than a third of the way through the season, Clemente already had 10 assists, and he also made some outstanding catches. “The Pittsburgh fans have fallen in love with his spectacular fielding and his deadly right arm,” wrote Les Biederman, a reporter who covered the Pirates.35

Clemente’s rambunctious style in the field could be costly, though. In May, he made a nice catch in St. Louis, but he hurt his finger and ran into the wall. The injury caused him to miss a few games.

Clemente’s hitting slumped as the season went along, in part because he still had trouble laying off pitches that were out of the strike zone. However, he became known as a good “bad-ball hitter,” able to make good contact on bad pitches. Jack Cassini, who had played in the minors with Clemente the year before, said, “He could hit. He didn’t need a strike. The best way to pitch him was right down the middle of the plate.”36

Clemente played 124 games for the Pirates in 1955 and had a batting average of .255. He walked only 18 times. Drawing bases on balls would never become a strong point for him. While it wasn’t a sensational rookie season, Clemente had earned a spot in the Pirates’ outfield. More than that, his exciting style of play made the fans look forward to seeing more of him.

Clemente returned to Puerto Rico in the fall of 1955. It had been reported that he might not play winter ball in his homeland and instead would begin college and study engineering.37 However, Clemente ended up back on the diamond, playing another season for Santurce.

Back on the mainland in 1956, Clemente had a new boss in Pittsburgh. Bobby Bragan had taken over as manager from Fred Haney. Bragan appeared to be well-liked by the players, although he quickly demonstrated his strictness. In the second game of the season, Clemente missed a signal for a bunt and Bragan fined him.38 He also fined another player, Dale Long. Biographer Kal Wagenheim wrote, “This harsh action worked like a shot of adrenalin. The club was soon fighting for first place in the league. Dale Long hit eight home runs in as many games. Clemente moved his batting average up to .348, fourth best in the league.”39

The Pirates were in first place in mid-June, but an eight-game losing streak dropped them to fifth and ended their pennant hopes. Even so, they avoided last place for the first time since 1951 and they were showcasing one of the major league’s most exciting players. In the outfield, Clemente had 17 assists, a sign of his strong throwing arm. At the plate, his .311 batting average was third-best in the National League. Two of his biggest hits were game-winning home runs. On Saturday, July 21, the Pirates trailed the Reds, 3-1, in the top of the ninth but had two runners on base as Clemente came to the plate. The Cincinnati pitcher was Brooks Lawrence, who had already won 13 games that season and hadn’t yet lost. Clemente changed that, hitting a three-run homer, to give the Pirates a 4-3 win and spoil Lawrence’s perfect record.

The following Wednesday, the Pirates were at home, playing the Chicago Cubs. Chicago led, 8-5, but Pittsburgh loaded the bases with no out. With Clemente due up, the Cubs brought in a new pitcher, Jim Brosnan. On Brosnan’s first pitch, Clemente hit a long drive to left-center field. Hank Foiles, Bill Virdon, and Dick Cole raced around the bases toward home plate with the runs that would tie the game. Clemente also tore around the diamond. Manager Bobby Bragan was coaching at third base and held up his arms, giving Clemente the signal to stop at third. With no one out and good hitters coming up, Bragan figured they’d still get Clemente home with the winning run and didn’t want to take the chance on him being thrown out at the plate. However, Clemente ignored his manager, kept running, and was safe at home. The inside-the-park grand-slam home run won the game for the Pirates.40

Bragan, who had fined Clemente earlier in the season for missing a sign, wasn’t happy about Clemente deliberately disobeying this one. However, he decided not to fine him.41

Clemente’s hits were the usual way for him to reach base because he rarely walked. He drew only 13 bases on balls in 1956, and at one point went 51 games without walking.42 Branch Rickey wasn’t concerned: “His value is in not taking bases on balls because he can hit the bad pitches. If I tried to teach him to wait for a good pitch, I’d simply make a bad hitter out of him. The cure would be worse than the disease. He’ll cure his own ailments simply by experience.”43

At the end of the season, Clemente headed home to play another season for Santurce in the Puerto Rican League. However, a couple of significant events took place between Christmas and New Year’s Day. First, Santurce owner Pedrín Zorrilla sold the team. A few days later, the new owner of the Cangrejeros sold several players, including Clemente, to Caguas-Rio Piedras. The trade was extremely unpopular and even caused the Santurce manager, Monchile Concepcion, to resign.44

Clemente was leading the league in batting average and had gotten at least one hit in 18 consecutive games when he was traded. He continued his hitting streak, which reached 23 to set a new Puerto Rican League record. His streak was snapped when he was held hitless in a game by Luis “Tite” Arroyo, a longtime friend and teammate on the Pirates who was pitching for the San Juan Senadores in the winter.45 Clemente finished with a batting average of .396.

His batting eye was certainly sharp, but Clemente’s back was continuing to bother him, and he reported a day late to spring training in 1957 as a result. Bobby Bragan made light of the backache because Clemente had always played well even when he had some aches and pains. “The case history of Clemente is the worse he feels, the better he plays,” reported The Sporting News, which quoted Bragan as saying, “I’d rather have a Clemente with some ailment than a Clemente who says he feels great with no aches or pains.”46

Clemente’s ability to play through pain and perform well may have contributed to charges that he wasn’t really hurt. However, this time the back problems forced him to miss the first two games of the season. In all, Clemente played in only 111 games for Pittsburgh in 1957 and his batting average dropped to .253. The back problems lingered into the winter, and Clemente didn’t play in the Puerto Rican League until mid-January of 1958.

The Pirates had finished tied for last in 1957, but they made a big jump in 1958 under manager Danny Murtaugh. Clemente, who was feeling better physically, helped them get off to a good start in their opening game. He had three hits, one of which tied the game in the eighth inning against Milwaukee. The Pirates eventually won in 14 innings.

Clemente continued to hit well. He had three hits again in a 4-3 win in Cincinnati on April 25. One was a double in the sixth inning when the Pirates were trailing, 1-0. Clemente eventually scored to tie the game. The next inning he broke the tie with a three-run homer.

Another game-winning home run came in Milwaukee on August 4. Clemente broke a 3-3 tie with two out in the top of the ninth with a home run off fellow Puerto Rican Juan Pizarro, who had also been a winter teammate.

A little over a month later, Clemente had an even more spectacular game, although he didn’t hit any homers. He had three triples, tying a National League record, in a 4-1 win over Cincinnati on September 8.

Clemente batted .289 in 1958. From right field, he continued to terrorize opposing baserunners, finishing with 22 assists. Fans loved it when a ball was hit his way with runners on base, rising in anticipation of seeing him uncork a strong throw.

Led by Clemente, the Pirates climbed from last place all the way to second, eight games behind the Milwaukee Braves.

Clemente didn’t play winter baseball in Puerto Rico in 1958-59. He wore a different uniform, for the United States Marine Reserves. He fulfilled a six-month military commitment at Parris Island, South Carolina, and Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. The rigorous training program helped Clemente physically. He added strength by gaining ten pounds and said his back troubles had disappeared. Clemente served as an infantryman in the Reserves until September 1964.47

When he reported to the Pirates in the spring of 1959, he complained of a sore right elbow. In May he made it worse when he hit the ground hard while making a diving catch. A few nights later, he had to be taken out of a game because he couldn’t throw overhanded. He missed more than a month and continued to feel pain after he returned to the lineup.48

Clemente played in only 105 games and batted .296 as Pittsburgh dropped to fourth place. But he and the Pirates were primed for better things in 1960.

For the first time in several winters, Clemente played a full season in the Puerto Rican League in 1959-60. He was on a new team, having been traded to the San Juan Senadores, and he had a batting average of .330. Clemente and the Pirates hoped that he was ready for a big season back in Pittsburgh.

Another encouraging sign was that he was free of injuries. Feeling good and tuned up from his winter play, Clemente got off to a great start in 1960. In the Pirates’ second game, at home against the Reds, he went three-for-three and drove in five runs as Pittsburgh won, 13-0. By the end of April, Clemente was batting .386. In 14 games, he had scored 12 runs, driven in 14, and hit three home runs. But he was just warming up. In Cincinnati, he had a home run and four RBIs on the first day of May. The 13-2 win was Pittsburgh’s ninth straight and the team was in first place.

The Pirates cooled off a bit, but Clemente stayed hot. In May, he had 25 RBIs in 27 games, raising his season total to 39. He helped Pittsburgh regain the top spot in the National League standings and was named the league’s Player of the Month by The Sporting News.

The Pirates battled for first with the San Francisco Giants and then the Milwaukee Braves. On the first Friday night in August, the Pirates were locked in a scoreless battle with the Giants at Forbes Field. Vinegar Bend Mizell was pitching for Pittsburgh and getting great help from his outfielders. Bill Virdon made a couple of good catches. Then Willie Mays led off the seventh inning for San Francisco with a long drive to right. Clemente chased the fly, reached out, and caught it, robbing Mays of an extra-base hit as he crashed into the outfield wall. He hurt his knee and also ended up with a gash in the chin that needed five stitches.49

Clemente stayed in the game the rest of the inning, but he was replaced by Gino Cimoli to start the eighth. Pittsburgh eventually won, 1-0, starting a four-game sweep of the Giants. Clemente missed the rest of the series as well as another three games.

He was out for a week. The day after he returned, he had a big game against the St. Louis Cardinals. St. Louis had beaten the Pirates the previous two nights and the Cardinals were in second place, only three games behind Pittsburgh. The Cardinals took the lead with a run in the top of the first inning. In the last of the first, Pittsburgh tied the game when Clemente singled home Dick Groat.

With the score still tied, Groat opened the third inning with a double, and Clemente followed with a homer. Clemente had another run-scoring single in the fourth as Pittsburgh won the game, 4-1. Clemente batted in all four of his team’s runs.

The Pirates swept a doubleheader from the Cardinals the next day to open up a six-game lead. No one came close to them the rest of the way. Except for one day, the Pirates had been in first place since May 29.

Clemente finished the 1960 season with a .314 batting average and hit 16 home runs, more than doubling his previous high. He also made the National League All-Star team for the first time.

Pittsburgh’s first pennant since 1927 put them in the World Series against the New York Yankees. Despite being outscored 46-17, the Pirates split the first six games to force a decisive seventh game.

New York came back from a 4-0 deficit to carry a 7-4 lead into the last of the eighth. The Pirates rallied, helped by a bad hop that turned a probable double-play grounder into a base hit. One run was in and Pittsburgh had runners at second and third with two out when Clemente came to bat against the Yankees’ Jim Coates. Clemente swung and topped the ball toward first base. Coates couldn’t get to it, and it was left to Moose Skowron to field it. Skowron had no chance of beating Clemente to the base, and Coates’s pursuit of the ball left the bag uncovered. Clemente zipped safely across the base, his helmet flying off, while the two Yankees watched helplessly.

Clemente’s hit drove in another run and the Pirates took a 9-7 lead when Hal Smith followed with a three-run homer. New York came back in the top of the ninth to tie the game, setting the stage for one of the most dramatic moments in Pittsburgh sports history–a Series-winning home run by Bill Mazeroski leading off the last of the ninth.

Clemente had had a hit in each of the seven games in helping the Pirates win the World Series.

Returning to his homeland following the 1960 season, Clemente skipped the first part of the Puerto Rican League season, but then joined the San Juan Senadores in the second half. Even after he became a star in the major leagues, Clemente continued playing winter ball well past the time that he needed to keep his batting eye sharp. He felt an obligation to the people of his homeland, who otherwise would not have a chance to see him play. Clemente is perhaps the most inspirational figure the island has ever known, and he took that responsibility seriously.

He frequently stood up for himself and his fellow Latin players, speaking out against injustices he saw. He approached this in the same manner in which he played–with a passion, sometimes an anger, which drove him on and off the field.

Much of his anger was justified. Although the game became more open to Latins after the breaking of the color barrier, certain attitudes and prejudices toward these players remained. Latin players were often accused of being lazy or faking an injury if they missed a game because they were hurt or ill. Clemente knew first-hand the feeling of being called a hypochondriac. He suffered through many ailments in his career and he burned when his manager or reporters didn’t believe him when he said he was hurt.

One of Clemente’s biographers, Kal Wagenheim, wrote, “The legend of his hypochondria became part of baseball’s folklore. He claimed so many ills–and performed so well despite them–that his plaints evoked skepticism or laughter.” Wagenheim also noted that Clemente had problems in the 1960s with Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh, who “reportedly accused him of feigning an injury and fined him for not playing.”50

Beyond the injuries and claims of hypochondria, Clemente maintained that Latin players often did not receive the recognition they deserved. Once again, Clemente was an example of this. After helping the Pirates win the National League pennant, and then the World Series championship, Clemente finished eighth in the voting for the league’s Most Valuable Player. Clemente thought he should have gotten more votes and finished higher in the balloting.

Each slight, whether at him or a fellow Latin, he took personally. He spoke out often, although some of the claims he made about being mistreated weren’t always entirely correct.

Phil Musick, a reporter who covered the Pittsburgh Pirates during the final years of Clemente’s career, said, “He was anything but perfect. He was vain, occasionally arrogant, often intolerant, unforgiving, and there were moments when I thought for sure he’d cornered the market on self-pity. Mostly, he acted as if the world had just declared all-out war on Roberto Clemente, when in fact it lavished him with an affection few men ever know.”

However, Musick added, “I know that through all of his battles . . . there was about him an undeniable charisma. Perhaps that was his true essence–he won so much of your attention and affection that you demanded of him what no man can give, perfection.”51

Clemente did eventually receive the respect he sought. Toward the end of his career, fans and reporters recognized his greatness on the field. More than that, they knew of his caring nature for all people.

Clemente said he rarely set goals, but that he did once: “After I failed to win the Most Valuable Player Award in 1960, I made up my mind I’d win the batting title in 1961 for the first time.”52

Clemente did exactly that, leading the National League with a .351 batting average. He hit 23 home runs, scored 100 runs and drove in 89. He led National League outfielders with 27 assists and won a Gold Glove for his fielding excellence for the first time. Clemente would win a Gold Glove every year for the rest of his career.

In Puerto Rico, Clemente played winter ball less often. He skipped the 1962-63 season altogether. It was the first time he hadn’t played in the Puerto Rican League other than the time he was in the Marine Reserves in 1958-59.

However, Clemente was back for a full season with San Juan in 1963-64. The Senadores finished third during the regular season but won the league playoffs and represented Puerto Rico in the International Series, which was played in Managua, Nicaragua. Author Thomas Van Hyning reports, “Clemente was a fan favorite and made a lot of fans in Nicaragua.”53 Clemente developed a fondness for the country and its people and would return again.

The race for the Puerto Rican batting title involved two National League stars—Clemente and Orlando Cepeda–and a young player on the verge of stardom in the American League, Tony Oliva. Back on the mainland in 1964, Oliva and Clemente led their respective leagues in batting average. Oliva, who credited his winter-league experience with helping his development as a hitter, had a .323 average in his first full season in the majors.54 Clemente’s .339 average was good for his second National League batting title.

The winter of 1964-65 was an eventful one for Clemente. He married Vera Cristina Zabala. He also began managing. In December of 1964, Clemente took over as manager of the San Juan Senadores. He still played, although less often. In his first game as manager, Clemente had two doubles off Dennis McLain of Mayaguez. “He drove in two runs with his second double and raced home on a wild throw, but twisted his left ankle slightly and left the game,” reported Miguel J. Frau in The Sporting News.55

Clemente later suffered a more serious injury. He was mowing the lawn at his home when a rock flew out of the mower and hit him in the thigh. He missed some games as a player, but when the league’s All-Star Game was played, Clemente felt obligated to make an appearance. He pinch-hit and singled, but he aggravated the injury. “I felt my thigh ligament pop and something like water draining inside my leg,” he said. Clemente had partially severed a ligament in his thigh, and he had to have surgery.56

The injury, combined with a fever, left Clemente weak, and he got off to a slow start in 1965 with the Pirates. Under new manager Harry Walker, the team also began poorly, losing 24 of their first 33 games. A 12-game winning streak followed, lifting Pittsburgh in the standings. Clemente got hot over this stretch, hitting .458 during the winning streak. The Pirates never overcame their slow start and finished third. Clemente led the league in batting average for the second year in a row and the third time in his career.

No one knew, though, that he was on the verge of his best season ever.

In addition to his other skills, Clemente was increasing his walk total in the mid-1960s. Early in the 1966 season, the Pirates were in Chicago, trailing the Cubs by a run. Clemente came to bat with two out and no one on base in the ninth inning. Cubs reliever Ted Abernathy got two strikes on Clemente. The Pirates were on the verge of losing, but Clemente remained patient. Abernathy’s next three pitches were outside the strike zone, and Clemente laid off them. The count was full. Clemente stayed alive by fouling off the next eight pitches. Finally, Abernathy missed again and Clemente was on base with a walk. Willie Stargell followed with a double and Clemente came home with the tying run. Pittsburgh won the game in extra innings.

The win kept the Pirates in first place. They stayed in the pennant race all season, battling the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers. At the end of August the Pirates and Giants were tied for first. On September 2, Clemente hit a three-run homer off Chicago’s Ferguson Jenkins that helped Pittsburgh beat the Cubs and take over sole possession of first place. It was the 2,000th hit of his career and his 23rd homer of the year, equaling his previous career high. In addition, it gave him 101 runs batted in, the first time he had ever reached 100 RBIs in a season.

He ended the season with career-highs in home runs (29) and RBIs (119). The Pirates finished third behind the Dodgers and Giants, but Clemente edged out Los Angeles’ Sandy Koufax for the Most Valuable Player award.

Clemente had another outstanding season in 1967. He led the league with a .357 batting average for his third batting title in four years and his fourth overall. In addition to 209 hits, Clemente walked or was hit by a pitch more than 40 times, and he reached base at least 40 percent of the time for the first time in his career.

Clemente had another outstanding season in 1967. He led the league with a .357 batting average for his third batting title in four years and his fourth overall. In addition to 209 hits, Clemente walked or was hit by a pitch more than 40 times, and he reached base at least 40 percent of the time for the first time in his career.

After having taken the previous winter off, Clemente played occasionally in the Puerto Rican League in 1967-68 and had a batting average of .382. Back on the mainland, things did not go well for him in 1968. The Pirates’ opener was delayed two days because of the assassination of Martin Luther King. Clemente homered in the first game, but his batting average fell to .222 at the end of May. He said he was having trouble swinging the bat because he had injured his right shoulder in a fall at his home in Puerto Rico in February of 1968. He added that he might retire from baseball if the shoulder didn’t get better.57

He improved over the last part of the season and finished with a .291 batting average, his lowest since 1958. Clemente didn’t play winter ball and rested his body. He felt good when spring training began in 1969, but then he hurt his left shoulder as he tried to make a diving catch and went back to Puerto Rico for treatment. Clemente returned in time for the start of the regular season, but for the second year in a row he got off to a slow start. In the latter half of May, after going hitless in the first game of a series in San Diego, his batting average had fallen to .225.

Clemente claimed something else happened–a strange and scary incident. He did not tell the story in public until a year later, but Clemente said he was kidnapped while in San Diego. According to Clemente, he was walking back to the hotel where the Pirates were staying after going out to eat. He said four men forced him into a car at gunpoint. They took him to an isolated area and took his wallet and his All-Star Game ring. “This is where I figure they are going to shoot me and throw me in the woods,” he told Pittsburgh writer Bill Christine more than a year after the incident. “They already had the pistol inside my mouth.” Two of the men spoke Spanish, and Clemente talked to one of them in Spanish. After that, the men returned Clemente’s money and ring and brought him back to his hotel. They even gave Clemente back the bag of chicken he had purchased at the restaurant. He said he did not report the incident to the police.58

Despite the harrowing event, Clemente finished the series in San Diego by getting three hits against the Padres and raised his batting average above .300 by mid-June. For a while it looked like he might lead the league again. He didn’t, but Clemente still finished the season with a batting average of .345. The Pirates didn’t do as well, finishing third in the new East Division of the National League.

After a slow start in 1970, the Pirates caught fire as they moved from Forbes Field, where they had played since 1909, to Three Rivers Stadium. Pittsburgh and New York fought for first place through July, with Chicago staying close. The Pirates were hanging in without Clemente. He was hit in the wrist with a pitch on July 25 and, except for one pinch-running appearance, was out of the lineup for more than a week. He returned on August 8 and had a double and a home run against the Mets.

Later in August, Clemente had five hits in each of two straight games. The first one came on a Saturday in Los Angeles. Clemente already had four hits as he came to the plate in the top of the 16th inning. He singled, stole second, and later came scored the go-ahead run as the Pirates beat the Dodgers, 2-1. The next day, the Pirates won again, 11-0. Clemente had five of Pittsburgh’s 23 hits in the game.

He had raised his average to .363, tops in the National League. However, he played little in September because of a bad back and did not win the batting title. The Pirates still won the National League East Division and advanced to the playoffs. Scoring only three runs in three games, however, they were swept by the Cincinnati Reds.

That winter, Clemente played for the last time in the Puerto Rican League. Although he played in only three games during the regular season, he appeared in one of the playoff series. In addition, he managed the San Juan Senadores in 1970-71. The Senadores’ opening game that season was against Santurce, which was managed by Frank Robinson. Both Robinson and Clemente had been mentioned as possibilities to be the first black manager in the major leagues.

After he got off to a slow start with the Pirates in 1971, he said, “My biggest mistake was managing in Puerto Rico this past winter. I had more responsibilities and did not get my rest. The long bus trips out of town, I have to make them because I am the manager. They take something out of me.”59

Willie Stargell took the lead with Pittsburgh in 1971. He set a major league record by hitting 11 home runs in April and continued his great hitting throughout the year. Stargell finished with 48 home runs and 125 runs batted in.

Although Stargell had emerged as the team’s star player, the team leader was still Clemente. He was receiving the recognition he had sought, and he was also showing he could continue playing with the same flair and hustle, even as he approached his 37th birthday. Clemente got off to a bad start, but he got hot in May and went on to finish the season with a .341 batting average. He was still outstanding in the field. In mid-June, Clemente preserved a shutout for Steve Blass, and a victory for the Pirates, on back-to-back plays. Pittsburgh held a 1-0 lead over Houston in the last of the eighth inning. The Astros had a runner on first with one out when Cesar Cedeno hit a soft liner to right field. Clemente hustled in and made a sliding catch of the ball before it could hit the turf. Bob Watson then hit a much harder drive toward the corner in right. Clemente raced toward the ball and made a twisting leap, grabbing the ball and robbing Watson of a two-run homer. Clemente crashed into the wall, bruising his ankle and elbow and cutting his knee. Astros manager Harry Walker, who had managed Clemente in Pittsburgh, said it was the greatest catch he ever made. Because of Clemente’s catch, the Pirates maintained their lead and then padded it with two more runs in the ninth. Blass finished with a 3-0 win but said, “That shutout belongs to Clemente.”60

The win gave the Pirates a 3 ½ game lead over the New York Mets and St. Louis Cardinals. Pittsburgh increased its lead to 9 ½ games at the All-Star break in July. The Pirates had several players in the All-Star game, including two starters–Willie Stargell in left field and Dock Ellis, who pitched. Clemente entered the game as a replacement for Willie Mays in the fourth inning. Later in the game, he hit his first home run in an All-Star Game.

Pittsburgh went on to win the East Division and beat San Francisco in the league playoffs to make it back to the World Series, against the Baltimore Orioles. Clemente turned the event into a showcase for his greatness.

Baltimore took the first two games before the series shifted to Pittsburgh. Clemente drove in the first run of the third game with a fielder’s choice. The Pirates added another run, but Baltimore came back on a home run by Frank Robinson to cut the lead to 2-1. Clemente led off the last of the seventh by grounding back to Mike Cuellar, who had briefly pitched for Clemente’s San Juan team in the Puerto Rican League the previous winter.61 However, Clemente hustled down to first so hard that Cuellar hurried his throw and threw wildly. Clemente reached base on the error and, after Stargell walked, Bob Robertson hit a three-run homer. Pittsburgh won, 5-1.

The next game was the first night game in the history of the World Series. The Orioles got off to an early lead with three runs in the top of the first. Pittsburgh came back with two in the bottom of the inning, and the Pirates rallied again in the third. With one out, Richie Hebner singled. Clemente then hit a long drive to right. It cleared the fence and looked like a home run to put the Pirates ahead. However, the ball was ruled foul after the umpires had a long discussion. The ball was foul, and Clemente had to resume his at-bat. He couldn’t come up with another long ball, but his single sent Hebner to second. One out later Al Oliver singled, scoring Hebner to tie the game. The score stayed at 3-3 until the Pirates pushed another run across in the seventh inning. Pittsburgh won the game, 4-3, and tied the World Series, 2-2.

The Pirates won again the next day as Nelson Briles held the Orioles to two hits. Clemente had a run-scoring single in the fifth inning to cap Pittsburgh’s scoring as the Pirates won, 5-0.

The Series shifted back to Baltimore, but Pittsburgh had the lead. Just as he had done in the 1960 World Series, Clemente had at least one hit in each of the games. In the sixth game, with two out in the top of the first, he tripled off the fence in left-center field. However, Willie Stargell struck out, and Clemente was stranded at third.

By the time Clemente came up again in the third inning, the Pirates had a 1-0 lead. Clemente made the score 2-0 by hitting a home run to right field. The Orioles came back and tied the game in the seventh. In the last of the 10th inning, Brooks Robinson hit a sacrifice fly that scored Frank Robinson, giving Baltimore the win and extending the series to a seventh game.

Cuellar and Pittsburgh’s Steve Blass were the starters in Game Seven, and both were sharp. Cuellar retired the first 11 Pittsburgh batters before Clemente came up with two out in the fourth. Cuellar threw him a high curve ball, and Clemente drove it over the left-center field fence. Clemente’s second home run of the series gave Pittsburgh a 1-0 lead.

The Pirates got another run in the eighth inning, which they needed. In the bottom of the eighth, Baltimore got the first two runners on base. Blass was able to work out of the jam with only one run scoring, leaving Pittsburgh in the lead. Blass retired the Orioles in order in the last of the ninth. Clemente’s homer had given the Pirates a lead they never gave up. Pittsburgh won the game, 2-1, and the Pirates were again champions of the world.

The Pirates had a number of pitchers who stood out, but when the voting was complete for the outstanding player of the World Series, the award went to Clemente. He had 12 hits, including two home runs, for a .414 batting average in the seven games.

There was no doubting his greatness nor his influence on the champion Pirates. Clemente had played in the All-Star Game, the World Series, had won the Most Valuable Player award, and had led the National League in batting average four times. He still had another milestone in his sights. “I would like to get 3,000 hits,” he said in 1971.62

The Pirates had a rough start in 1972. They climbed in the standings and by the last half of June had taken over first place for good. Clemente was also doing well even though he had an intestinal virus that caused him to miss a few games. By the end of June, his batting average was .315, and he was making good progress toward the mark of 3,000 hits. On July 9, he got his 78th hit of the season, leaving him only 40 short. However, the virus returned, and Clemente left the Pirates to go back to Pittsburgh for treatment. He was out of the lineup for two weeks, then came back and got a big hit in a Pirates win on July 23.

Clemente missed another four weeks with strained tendons in both heels. Over a 40-game span between July 9 and August 22, he started only one game. Fortunately, the Pirates were still playing well and opened up a big lead in the National League East Division, but the illness and injuries had slowed Clemente in his drive toward 3,000 hits.

At the end of August he had 30 hits to go. He hit well in September and was within striking distance by the final week of the season. On Thursday night, September 28, he got his 2,999th hit off Steve Carlton of the Phillies. Because the game was in Philadelphia, he was taken out so he could get his 3,000th hit before the home fans.

Even this event would not happen without a bit of controversy as the Pirates opened a series against the New York Mets in Pittsburgh. Facing Tom Seaver in the first inning, Clemente hit a chopper up the middle. Second baseman Ken Boswell bobbled the ball, and Clemente reached first. Official scorer Luke Quay ruled the play an error. Seaver allowed only two hits, neither to Clemente, in winning his 20th game of the season. After the game, Clemente complained about the scoring decision and later made accusations that official scorers through the years had deprived him of two batting titles. Part of the outburst was a result of Clemente thinking (erroneously) that the scorer in the game was Charley Feeney, a local sportswriter who Clemente thought had deprived him of hits on borderline calls in the past.63

Even this event would not happen without a bit of controversy as the Pirates opened a series against the New York Mets in Pittsburgh. Facing Tom Seaver in the first inning, Clemente hit a chopper up the middle. Second baseman Ken Boswell bobbled the ball, and Clemente reached first. Official scorer Luke Quay ruled the play an error. Seaver allowed only two hits, neither to Clemente, in winning his 20th game of the season. After the game, Clemente complained about the scoring decision and later made accusations that official scorers through the years had deprived him of two batting titles. Part of the outburst was a result of Clemente thinking (erroneously) that the scorer in the game was Charley Feeney, a local sportswriter who Clemente thought had deprived him of hits on borderline calls in the past.63

The next afternoon Clemente struck out in the first inning. The game was scoreless when he came up again, leading off the fourth. He hit a long fly toward left-center field. The ball hit the fence on one bounce, and Clemente cruised into second with a double, the 3,000th hit of his career. The Pittsburgh fans stood and applauded Clemente, who raised his cap to show his appreciation. That hit started a three-run rally, and the Pirates won the game, 5-0. Bill Mazeroski pinch hit for Clemente in the fifth inning.

Clemente played in only one of Pittsburgh’s final three games as he rested for the playoffs. The Pirates played Cincinnati and looked like they were on their way back to the World Series. Pittsburgh carried a 3-2 lead into the last of the ninth inning of the decisive fifth game. However, Johnny Bench tied the game with a home run, and the Reds scored the winning run on a wild pitch.

As usual, Clemente went back to Puerto Rico. Although he didn’t play baseball, he managed a Puerto Rican team that went to the Amateur Baseball World Series in Nicaragua. The Puerto Rican team finished third in the tournament.64

Clemente was back home a few weeks later when the city of Managua was racked by a massive earthquake on December 23. He had gotten to know people during his visits to Nicaragua. He was concerned about the people there and wanted to help.

Clemente got busy organizing a committee to raise money and get other items, such as medicine and food, that could be sent to Nicaragua. Through Christmas, he worked on the relief efforts. He finally decided he would go on one of the cargo planes that were flying the supplies to the stricken area.

A little after 9 p.m. on New Year’s Eve, as others in Puerto Rico were celebrating, the plane took off. Besides Clemente, four other people were on board. Almost immediately, the plane had problems, and the pilot tried to return to the San Juan airport. Before the plane could make it back, however, it crashed into the Atlantic Ocean about a mile from the coast.

The fate of the people on board was not immediately known. But it soon became clear. The five men on the plane, including Roberto Clemente, were dead.65

People, not just baseball fans, mourned the loss of Clemente, who left behind his wife, Vera, and three sons, Roberto, Jr., Luis Roberto, and Roberto Enrique.

Normally, a player cannot be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame until at least five years after he stopped playing. Because of the circumstances, an exception was made for Clemente. A special election was held, and he received enough votes to be elected. In the summer of 1973, Clemente became the first player from Latin America to be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

There were other honors. An award, established in 1971 to honor a player for his accomplishments on and off the field, was renamed the Roberto Clemente Award.

Clemente had dreamed of establishing a Sports City for young people in Puerto Rico. He had a vision for a place where young people could come and play as well as read and learn other skills they would need in life. Vera Clemente continued her husband’s work, aided by son Luis, and while the project remains uncompleted, the Foundation that was established works to support clinics, sports activities, and similar efforts.

Although he is gone, all sorts of reminders of Clemente still exist. More than anything, Roberto Clemente left behind memories of how he played the game on the field and how he lived his life off it.

Sources

Retrosheet (http://retrosheet.org) provided game-by-game details of Clemente’s performance. The information used was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet.

Notes

1 Peter C. Bjarkman, Baseball with a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin American Game (Jefferson: North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1994), 262.

2 Kal Wagenheim, Clemente! (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1973), 15.

3 Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 1998), 4.

4 Telephone interview with Monte Irvin, June 30, 2005.

5 “Roberto Hit Ten HRs in ‘Day-Long’ Slugfest,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1960: 6.

6 Wagenheim, 24.

7 “Starred in Javelin, Jumps Before Turning to Diamond,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1960: 6.

8 Markusen, 8.

9 Les Biederman, “Pride Pushes Clemente: ‘I Can Hit With Best’,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1964: 11.

10 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1999), 39.

11 Frank Graham, Jr., “Spanish-Speaking Al Campanis Lures Latin Talent for Dodgers,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1955: 21.

12 E-mail correspondence with Buzzie Bavasi, June 3, 2005.

13 Santiago Llorens, The Sporting News, January 20, 1954: 23.

14 The Sporting News, March 3, 1954: 26.

15 The bonus rule in effect at that time is chronicled in Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953-1957 (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1997).

16 Les Biederman, “Dodgers Signed Clemente Just to Balk Giants,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1955: 11.

17 Wagenheim, 35; Markusen, 33-34.

18 The claim that the Dodgers would not start five blacks in the same game was made by Wagenheim on page 35 of Clemente! Box scores of Brooklyn Dodgers games in 1954 from The Sporting News indicate four instances in which Jim Gilliam, Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, Sandy Amoros, and Roy Campanella were all in the starting lineup: July 17, August 24, September 6 (second game), and September 15.

19 E-mail correspondence with Buzzie Bavasi, June 3, 2005.

20 Phil Musick, Who Was Roberto? A Biography of Roberto Clemente (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1974). See also Wagenheim and Markusen.

21 The game-by-game analysis of the 1954 season was done through box scores of Montreal Royals games, published in The Sporting News in 1954, and cross-checked by SABR member Neil Raymond from box scores in Montreal newspapers.

22 Musick, 89.

23 Musick, 89.

24 Telephone interview with Jack Cassini, June 20, 2005.

25 E-mail correspondence with Buzzie Bavasi, June 3, 2005.

26 “Jack Hernon, “Backward Buccos Refuse to Go Overboard on Rookie,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1955: 18.

27 Pito Alvarez de la Vega. “Mays, Gomez & Co. on Top in Puerto Rico: Santurce Takes Over Lead from Caguas; Willie Ups Swatting Average to .423,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1954: 24.

28 Wagenheim, 43.

29 Interview with Don Zimmer, July 2, 2005.

30 Jack Hernon, “Clemente a Gem – in Need of Polish,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1955: 4.

31 Jack Hernon, “Haney’s Sizeup on Bob Clemente ‘Much to Learn’,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1955: 30.

32 http://www.bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=1187&pid=14117 Frank Thomas biography by Bob Hurte; Jack Hernon. “Holdouts Thomas and Law Absent as Bucs Start Drills” The Sporting News, March 9, 1955: 33.

33 The Sporting News, March 16, 1955: 27; “Uniform Numbers Range from 1 to 81,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1955, 28; Thomas E. Van Hyning. Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1995), 53.

34 Jack Hernon, “Haney’s Young Bucs Shaking off Buck Fever,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1955: 11.

35 Les Biederman, “Clemente, Early Buc Ace, Says He’s Better in Summer,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1955, 26.

36 Telephone interview with Jack Cassini, June 20, 2005.

37 Les Biederman, “Clemente, Early Buc Ace, Says He’s Better in Summer.”

38 “Bragan Cracks Down Early, Fines Clemente, Long $25,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1956: 21; Les Biederman, “Bear-Down Bragan Means Business, Buc Fans Learn,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1956: 7.

39 Wagenheim, 67.

40 Irving Vaughan, “7-Run Cub 8th Isn’t Enough! Pirates Win, 9 to 8, on Clemente Homer,” Chicago Tribune, Thursday, July 26, 1956: 6, 1.

41 “Clemente Ignored Stop Sign on ‘Slam,’ But Escaped Fine,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1956: 18.

42 Les Biederman, “Clemente in 50 Games Without Walk,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1956: 18.

43 Oscar Ruhl. “Rickey Rates Clemente as Top Draft Dandy,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1957: 15.

44 Pito Alvarez de la Vega, “New Owner Peddles Trio of Santurce’s Stars to Flag Rival,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1957: 21.

45 Pito Alvarez de la Vega, “Bilko Released in Economy Move; Clemente Sets 23-Game Hit Mark,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1957: 21.

46 “Clemente, Best When Ailing, Reports Late With Backache,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1957: 10.

47 “Clemente to Start Six-Month Marine Corps Hitch, Oct. 4,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1958: 7; “Buc Flyhawk Now Marine Rookie,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1958: 13; The Sporting News, January 21, 1959: 9.

48 “Clemente Put on Disabled List and Baker Released by Bucs,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1959: 13.

49 Bob Stevens, “Little Things Add Up to Big Plunge for Snoozing Giants,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1960: 13, 18.

50 Wagenheim, 106.

51 Musick, 14-15.

52 Les Biederman, “Clemente–The Player Who Can Do It All,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1968: 11.

53 Thomas E. Van Hyning. Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad, 66.

54 Interview with Tony Oliva, June 5, 2005.

55 Miguel J. Frau, “Puerto Rico: Senators Dip As Clemente Grabs Reins,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1965: 27.

56 “Clemente May Have Trouble As Result of Thigh Injury,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1965: 25.

57 Les Biederman, “Shoulder Sore; Clemente Says He May Retire,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1968: 18.

58 “Clemente Reveals Close Call With Kidnapers,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1970: 24.

59 “Clemente Laments Managing,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1971: 14.

60 Charley Feeney, “Greatest Catch? This One by Roberto Will Do,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1971: 7.

61 Phil Jackman, “Orioles Shrug Off Cuellar’s Winter-Ball Woes,” The Sporting News, December 26, 1970: 37.

62 Charley Feeney, “Clemente Sets 3,000 Hits As Wish on 37th Birthday,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971: 9.

63 Charley Feeney, “Roberto Collects 3000th Hit, Dedicates It to Pirate Fans,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1972: 15.

64 “Veteran Cuban Team Captures Amateur Title; U. S. Runner-Up,” The Sporting News, December 30, 1972: 46.

65 “Baseball Mourns Loss of Buc Star Clemente,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1973: 42.

Full Name

Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker

Born

August 18, 1934 at Carolina, (P.R.)

Died

December 31, 1972 at San Juan, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.