Roxy Walters

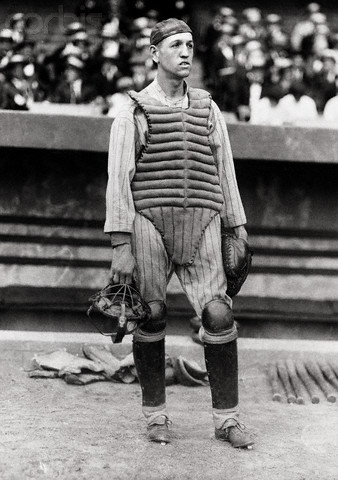

The Saskatoon Quakers welcomed a new catcher in 1913, 20-year-old Roxy Walters. He was never a large man; his listed playing height when he reached the majors was 5-feet-8 and he weighed 160 pounds, a stature at which he might have proved a target for a baserunner who confronted him blocking the plate. But he seems to have proved solid enough, ultimately playing in 11 major-league seasons, largely in a backup role.

The Saskatoon Quakers welcomed a new catcher in 1913, 20-year-old Roxy Walters. He was never a large man; his listed playing height when he reached the majors was 5-feet-8 and he weighed 160 pounds, a stature at which he might have proved a target for a baserunner who confronted him blocking the plate. But he seems to have proved solid enough, ultimately playing in 11 major-league seasons, largely in a backup role.

Walters played in 92 games for Class D Western Canada League’s Saskatoon club and he hit .270, with a .970 fielding percentage. In 1914 he played in 126 games and improved his average to .311. Saskatoon took first place in the six-club league. A note in The Oregonian from Portland indicated that he’d been in Portland before Saskatoon and in the Western Tri-State League, before his time with the Quakers.1

Indeed, he’d been “in charge of a draying concern” in San Francisco in the winter of 1912 when a Portland man signed him for the Northwestern League team, along with Harry Heilmann and two others.2

Walters had been signed for the Portland Colts by Jimmy Richardson, as an outfielder, but was released after a few days – “too small ever to make a catcher,” said Portland’s Walter McCredie.3 Walters then “drifted around” for a bit before landing in the Western Canada League. The cost to Saskatoon? The train ticket from Portland.4 His older brother, Frank “Cutey” Walters, had played some “outlaw ball” for San Jose as an outfielder in the California League.5

Roxy’s work for the Canadian team earned him an elevation to Class B ball with Waco (Texas League) in 1915, and a brief look-in at major-league play. He was one of three players sold by the Saskatoon club to Waco for $1,200.6 Walters hit .325 in 108 games for Waco – leading the league, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram – and made his major-league debut with the New York Yankees on September 16, 1915.7 Bobby Gilks of the Yankees had acquired his rights on behalf of the New York team on July 23. Waco won the Texas League pennant in 1915.

“I’m almost staking my reputation on Walters. I have seen all the catchers that ever came out of the Texas league, including Killefer, and I think the Waco youngster will be the best of them all. He’s the smartest lad I’ve seen in years. I mean baseball smart.”8 “Yankees Buy A Wonder,” headlined a brief story in the Boston Herald.9 He was to report after the Texas League season was over on September 6. The special dispatch to the Herald said, “He is the sensation of the league, and is recognized as the brainiest and fastest man that ever played in this league.” The Springfield Republican later indicated the sale price had been $5,000.10

Harry Dix Cole noted his debut in Sporting Life, writing, “Walters, the catcher from Waco, made his initial appearance in Thursday’s game against the White Sox, and handled the deliveries of Shawkey and Cole in fine style. His throwing was particularly good.”11 He’d played the game, batting eighth, and the New York Times averred, “Walters behaved like a real catcher, and if he works much the fans will forget that there ever was such a person as Ed Sweeney on the club.”12

Walters didn’t return to the minor leagues until 1926.

This was not the Roxey (sometimes Roxie or Roxy) Walters who had played first base for the Central Association’s Muscatine Wallopers in 1912; that Roxey had a career dating back to 1900 and his name was Louis. Alfred John Walters was “our” Roxy, born in San Francisco on November 5, 1892. His father, John Jacob Walters, was a painter from Illinois born of a German father and French mother. John Jacob married Laura Bell, from Indiana. Laura was widowed by 1910, working as a wet nurse for a private family. She had two children in the home at the time, George, 21, a wrapper in a dry-goods store, and Alfred, 17, who was working as a shipping clerk for a freight-transfer company. The two boys had elder siblings born in the late 1870s – sister Bertie and brother Harry.

Al Walters grew up playing scrub games on the lots of San Francisco before he got the opportunity to play for Saskatoon, and he’d enjoyed some immediate success, earning the first-string catching job after just a couple of weeks and seeing Saskatoon win the season’s first-half championship.13

Walters began 1916 as the backup catcher for manager Wild Bill Donovan and the Yankees and by the end of May was batting .289 after his first 13 games. He was the backup for Les Nunamaker. Walters played in 66 games, with a .266 batting average, and Nunamaker (batting .296) in 91, but Nunamaker drove in only 28 runs to Walters’ 23. Roxy apparently made a favorable impression with his defense and bat, and with his “pep.” More than one newspaper article declared that the two “finds” of the 1916 season were Walters and Rogers Hornsby.

Walters never felt his size was a problem. On August 3 he was bowled over by Detroit’s Bobby Veach at the plate and he lost his grip on the ball, the run that scored winning the game for the Tigers. Walters was asked if his being the smaller man was the problem. “No, that didn’t have anything to do with it,” he said. “The trouble was that I didn’t realize how close Veach was to me and wasn’t braced when he struck me. It doesn’t matter how big they are. All I want is time to brace myself and then I can hang onto the ball.”14

Opposing baserunners soon learned that he wasn’t easy to run on. He threw out 1.57 runners per game in 1916.15

After the season Roxy married Miss Florence Herrmann of San Francisco on November 16. She was a native of California but of immigrant parents, her mother from Ireland and her father from Germany. They ultimately had two children, Henry and Robert.

Walters as a catcher departed from the typical burly, slow stereotype and Baseball Magazine acknowledged that in 1917, saying he “covers ground like a shortstop. It’s a real treat to see him back up first base. And he’s got the push and ambition of Ty Cobb.”16

Roxy didn’t get all the work he’d expected in 1917, though, in part because of a broken finger he’d suffered on August 22. He worked in 61 games in all, batting .263, but hadn’t lost that drive and ambition. His next game behind the plate was on September 29 and he made what some papers called “the most thrilling catch” of the season, catching a foul ball after a long run that took him tumbling into the Yankees’ dugout. He caught the ball in both hands and fell to the ground – after which he immediately popped up, ready to fire the ball to an infielder should Joe Jackson try to tag up at first and run to second base.17

Les Nunamaker had been the principal catcher for the Yankees in 1917, but they traded him in January and it looked as though Walters would inherit the position. As it turns out, rookie Truck Hannah got the most work in 1918, playing in 90 games during the war-shortened season. Walters played in 64 and hit only .199. Hannah hit for a .220 average; he’d gotten the break because Walters had suffered one – a broken finger on a foul tip in an April 5 exhibition game in Columbia, South Carolina.

In December 1918 the Yankees and Red Sox pulled off a seven-player trade that saw Walters go to Boston with Ray Caldwell, Frank Gilhooley, and Slim Love (and $15,000) for Dutch Leonard, Duffy Lewis, and Ernie Shore. Walters played the next five seasons for the Red Sox, though only in 1920 did he rank first among games caught. Although the three players the Red Sox gave up all seem in retrospect to be far bigger names than anyone the team acquired, at the time Walters was seen to be a very significant addition and the Boston Herald’s Burt Whitman – after acknowledging the skepticism at the time – even wrote that reliable baseball men had told him that Walters was “a tip-top gem” who “will almost make up for all three.”18 But that didn’t show in his play, and the Red Sox saw catcher Wally Schang hit .306, against which Walters’ .193 paled.

In the offseason Walters, Lefty O’Doul, and four other ballplayers were all hired for the winter to work as firefighters at the Presidio in San Francisco.19

In 1920 Walters got his most work as a member of the Red Sox, playing in 88 games but still hitting around .200 (he hit .198 with 28 RBIs, but walked enough to enjoy a .303 on-base percentage.) He never hit a home run at any point in his big-league career.

Walters played in 54 games in 1921 and 38 games in 1922, hitting .201 and .194 respectively. Muddy Ruel was Boston’s first-string catcher both years. Val Picinich took over as Red Sox lead catcher in 1923, but Walters was able to bump up his average to .250, playing in 40 games despite now being third on the depth chart, behind Ruel and Al DeVormer. Throughout, his defense was solid and he left the game with a .975 major-league fielding percentage.

There was a lot of turnover on the Red Sox team, as the team plunged to the AL basement, and by the end of 1923 Walters was the last player who’d been on the team as recently as 1920, the last player from the Harry Frazee era. In January 1924 he was traded, too, sent to Cleveland on January 7 with George Burns and Chick Fewster for Dan Boone, Joe Connolly, Steve O’Neill, and Bill Wambsganss.

For the Indians, he played rather little – 32 games in 1924 (and seven of them at second base, where he was error-free) and just five games in 1925, his last season in the majors. He hit .257 and .200. He was released in early September 1925. The Boston Herald, for one, lamented his release, writing that he had been a popular favorite while in Boston and saying that while he “never really was heavy enough to stand the gaff,” it was “his weakness with the stick that really caused his downfall.”20

Walters’ last two years in baseball were in 1926 and 1927, as a backup catcher for the Mission Bells club of San Francisco, playing at Recreation Park in the Pacific Coast League. He was in 86 games in 1926, batting .182, and then in 66 games in 1927, hitting .210. For a week or two in April and very early May 1927, he ran the team after manager Bill Leard was relieved of his position.21

After baseball, Walters worked in the oil industry. In 1930 the family was living in Oakland and he was employed as a gas adjuster for the gas company. At the time of the 1940 census, he was perhaps following in his father’s footsteps, working as a painter in the oil industry. The family was in San Francisco.

Walters died at his Alameda, California, home from cardiac failure on June 3, 1956.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Walters’ player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

2 The Oregonian, December 8, 1917.

3 Ibid.

4 The Oregonian, October 3, 1915, and December 8, 1917.

5 San Jose Mercury News, February 10, 1916.

6 Seattle Daily Times, February 14, 1915.

7 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 19, 1915.

8 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 22, 1915.

9 Boston Herald, July 24, 1915.

10 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, May 7, 1916. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 30, 1916, said the sale price had been $2,500.

11 Sporting Life, September 25, 1915.

12 New York Times, September 17, 1915.

13 J.C. Kofoed, “The Live Wire of American League Catchers,” Baseball Magazine, January 1917, Vol. XVIII No. 3, 63-65.

14 Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, September 9, 1916. The New York Times game story said Walters had been set but was just bowled over due to the differences in size – though in fact Veach is listed with the same 160 pounds playing weight and had only three inches on Walters.

15 Hartford Courant, December 28, 1916.

16 Kofoed, “The Live Wire,” 63.

17 Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, October 12, 1917; Washington Evening Star, October 14, 1917.

18 Boston Herald, January 15, 1919.

19 San Jose Evening News, November 11, 1919.

20 Boston Herald, September 25, 1925.

21 The Sporting News, April 28 and May 5, 1927.

Full Name

Alfred John Walters

Born

November 5, 1892 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

June 3, 1956 at Alameda, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.