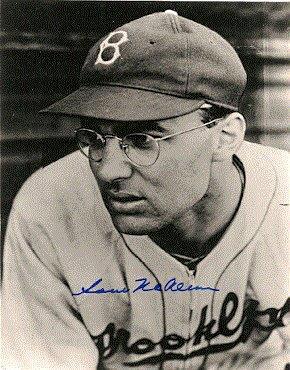

Sam Nahem

Sam Nahem was a so-so pitcher who logged a 10–8 won-loss record and a 4.69 ERA in four partial seasons with the Dodgers, Cardinals, and Phillies between 1938 and 1948.

Sam Nahem was a so-so pitcher who logged a 10–8 won-loss record and a 4.69 ERA in four partial seasons with the Dodgers, Cardinals, and Phillies between 1938 and 1948.

Despite this unremarkable record, Nahem was a remarkable major leaguer in many ways. He was the only Syrian and one of the few Jews in the majors during that period. Nahem not only had a college education — a rarity among big league players at the time — but also during off-seasons earned a law degree, which he viewed as his fallback job in case his baseball career faltered. He was also an intellectual who loved classical music and American, Russian, and French literature.

He was also one of the few big league pitchers — possibly the only one — who threw exclusively overhand to left-handed batters and exclusively sidearm to right-handed hitters.

Nahem was a right-handed pitcher with left-wing politics. He may have been the only major leaguer during his day who was a member of the Communist Party. After his playing days were over, Nahem worked for 25 years in a chemical plant, where he became a union leader. His political activities caught the attention of the FBI, which put Nahem under surveillance.

But most important in terms of his baseball career, Nahem was a key player in a little-known episode in the battle to desegregate baseball. Like many other radicals in the 1930s and 1940s, Nahem fervently believed that baseball should be racially integrated. While serving in the Army during World War II, he challenged the military’s racial divide by organizing, managing, and playing for an integrated team that won the U.S. military championship series in Europe in September 1945, a month before Jackie Robinson signed a contract with the Dodgers that broke major league baseball’s color bar.

Samuel Ralph Nahem’s parents — Isaac Nahem and Emilie (nee Sitt) Nahem — immigrated to America from Aleppo, Syria in 1912. Born in New York City on October 19, 1915, Nahem, one of eight siblings, grew up in a Brooklyn enclave of Syrian Jews. He spoke Arabic before he learned English.

Nahem demonstrated his rebellious streak early on. When he was 13, Nahem reluctantly participated in his Bar Mitzvah ceremony, but refused to continue with Hebrew school classes after that because “it took me away from sports.” To further demonstrate his rebellion, that year he ended his Yom Kippur fast an hour before sundown. Recalling the incident, he called it “my first revolutionary act.”1

The next month — on November 12, 1928 — Nahem’s father, a well-to-do importer-exporter, traveling on a business trip to Argentina, was one of over 100 passengers who drowned when a British steamship, the Vestris, sank off the Virginia coast.

Within a year, the Great Depression had arrived, throwing the country into turmoil. With his father dead, Nahem’s family could have fallen into destitution. “But fortunately we sued the steamship company and won enough money to live up to our standard until we were grown and mostly out of the house,” Nahem recalled. He remembered how, at age 14, he “used to haul coal from our bin to relatives who had no heat in the bitterly cold winters of New York.” So, despite his family’s own relative comfort, “I was quite aware of the misery all around.” That reality, Nahem remembered, “led to my embracing socialism as a rational possibility.”2

Education was Nahem’s ticket out of his insular community and into the wider world of sports and politics. While Nahem was still a teenager, an older cousin, Ralph Sutton, as well as his younger brother Joe and first cousin Joe Cohen, exposed him to radical political ideas. Sutton also mentored Nahem to appreciate Shakespeare and classical music.

In 1933, in the midst of the Depression, Nahem entered Brooklyn College, whose campus was a hotbed of political radicalism and activism. It was part of the taxpayer-funded City College system, which was known as the “poor man’s Harvard.” At the time, many of its students came from working class, immigrant Jewish families. Students espoused every variety of radical ideas, including anarchism, socialism, and Communism. Having already been attracted to the Communist Party by his cousin Ralph, Sam was soon participating in its campus activities.

Nahem was better off economically than most of his fellow students, but he quickly absorbed the campus’ leftist political atmosphere while, as an English major, immersing himself in his love of literature.

Although a brilliant student and a committed, idealistic activist, it was on the athletic field that Nahem really stood out. As a teenager, Nahem played baseball and football on Brooklyn’s sandlot teams because he didn’t make the teams at New Utrecht High School. He started off as a catcher but shifted to pitching when he began wearing glasses because they couldn’t fit beneath the catcher’s mask.3 He quickly grew in size, reaching 6-feet-1 and 190 pounds in college at a time when the average adult male was 5-feet-8.4 At Brooklyn College he became a top-flight athlete, pitching for the baseball team and playing fullback on its football team.

During his freshman year, Nahem recalled, “I really emerged as a personality, different from the shy, unaggressive, and, yes, uninteresting (but handsome) boy I was.” Nahem began dating girls and excelled in his English classes, where he was often the teacher’s pet, “especially since I was an athletic hero.” “I do recall the interest I awakened in my professors by my feats. ‘He throws a good curve and understands modern poetry! He knows how to use big words!’” He was drawn to Russian and French literature as well as such American writers as Hemingway, Faulkner, Dreiser, and Jack London.5

The New York Times, the Brooklyn Eagle, and other daily papers frequently reported on Nahem’s exploits on the gridiron and the diamond. “Who can deny a certain thrill in seeing one’s name in print?” Nahem recalled years later.6 In the spring of 1935, following a good football season, Nahem was back in the news as Brooklyn College’s ace hurler. “Nahem Stars on the Mound and at Bat,” the Times headlined its April 26, 1935 story, reporting that he not only defeated Fordham University by a 3-2 margin, but, batting fourth in the lineup, also got two hits and scored his team’s first run.

At the end of his sophomore year, Nahem earned a tryout with the hometown Brooklyn Dodgers, managed by Casey Stengel. Nahem told two versions of how he earned a Dodgers contract.

“One morning when I was pitching batting practice he (Stengel) grabbed a bat and got up there to hit against me,” Nahem recalled. “Maybe it was because I looked easy to hit. I bore down hard, and Casey didn’t get the ball out of the infield. So he promoted me — from morning batting practice pitcher to afternoon batting practice pitcher!”7 In another rendition, Nahem recollected, “I was throwing batting practice and an errant fastball hit this famous Okie pitcher, Van Lingle Mungo, in the ass. After the tryout, Stengel put his arm around me and said, ‘We’ll sign you up. If you can hurt that big lard-ass, you must have something on the ball.’”8

When Nahem told his mother that he was going to play professional baseball, she asked, “When are you going to quit those kid jobs and get a job?”

“I said, ‘I’m making $100 a week,’” Nahem recalled. “She said, ‘Go play!’”9

Nahem dropped out of college to play professional baseball.10 The Dodgers sent him to their minor league franchise in Allentown, Pennsylvania (in the Class-A New York-Pennsylvania league) for the 1935 season.11 He had a 2-5 record and an 8.42 earned run average.12 He started the 1936 season with Allentown but the Dodgers demoted him in Juneto a Class D team in Jeanerette, Louisiana (in the Evangeline League).13 He posted a 5-5 record and a 3.75 earned run average for Jeanerette in 1936. He batted .270 (10 for 37) and was occasionally used as a pinch hitter.14

During those two seasons in Allentown and Jeanerette, Nahem used an alias, “Sam Nichols,” perhaps to maintain his eligibility as an amateur athlete in case he didn’t succeed as a professional athlete and wanted to return to Brooklyn College and play on its sports teams again. But Sam’s secret wasn’t very well-hidden. The descriptions of him in the newspapers that covered the Allentown and Jeanerette teams reveal that “Nichols” was clearly Nahem. They referred to “Nichols” as the “bespectacled young right hander.”15 Several stories reported that he had graduated from Brooklyn College.16 (He actually left college after his sophomore year). They identified him as Jewish. A column in the Allentown Call noted that “The Allentown Brooks this season may have one of the rarities of organized baseball, an all-Jewish battery,” explaining that the team’s catcher, Jim Smilgoff is “of Hebraic extraction” while Sam Nichols is “also of Jewish parentage.” The column also reported that “Don’t say that we told you, but Sam Nichols answers to the name of Hassel (sic) Naham when the tax collector comes around over in Brooklyn,” using an unfamiliar first name and misspelling Sam’s last name.17

Starting in 1935, Nahem began attending St. John’s University during his off seasons. He earned his law degree and passed the bar in December 1938.18

In 1937 the Dodgers promoted him to their Clinton, Iowa team in the B-level Iowa-Indiana-Illinois league, where he had an outstanding season, pitching in 21 games, winning 15 games, losing only 5, and making the league’s All-Star team.19 In 1938, the Dodgers advanced him to their A-level Elmira, New York team, where he had a 9-7 record.

On September 28, the New York Times reported that “Sam Nahem, southpaw [sic]20 hurler for Elmira and formerly of Brooklyn College, reported to the Dodgers yesterday.” A few days later, October 2, the last day of the 1938 season, the 22-year old Nahem made his major league debut. He pitched a complete game to beat the Phillies 7-3 at Shibe Park in Philadelphia on just six hits. He also got two hits in five at bats and drove in a run, thus ending the season with a .400 batting average.21

Despite his stellar debut, the next year the Dodgers sent him back to the minors. He began the 1939 season playing for the Montreal Royals, where he won one game and lost three. Burleigh Grimes, a Hall of Fame pitcher who was Nahem’s manager with Montreal, taught him how to throw a slider. At the time, Nahem was one of the few hurlers who used that pitch, which he described as “halfway between a fastball and a curve.”22 In July, the Dodgers assigned Nahem to their Nashville Volunteers team. The Dodgers brought Nahem back to Brooklyn at the end of August but didn’t send him to the mound, and he was back in Nashville within a few weeks. He won eight games and lost six games for the Volunteers. The Times called him “Nashville’s ace hurler, Solemn Sam Nahem.”23

As the Dodgers spring training got underway in Florida in February 1940, the Times wrote that Nahem “the St. John’s University Law School graduate, is rated a great pitching prospect.”24 That same month, in a profile of Nahem, New York Post sportswriter Stanley Frank called him “the very jewel of a rookie” (even though he had pitched for the Dodgers in 1938). Frank quoted Dodgers manager Leo Durocher saying “I remember him [Nahem] well. Big and strong with a great fastball, but it didn’t do much.” Frank then quoted Nahem, rebutting Durocher’s assessment: “It does now. It sinks when I’m good, but my best pitch is that slider. I didn’t have it when the Dodgers last saw me.”25

Despite Nahem’s bravado, he pitched poorly during spring training. In one game, in what can only be viewed as an act of cruelty, Durocher allowed Nahem to face 19 batters and give up 13 runs in the ninth inning before taking him out. 26

An article in the Nashville Tennessean in March, while he was at spring training in Florida, reported that Nahem was thinking of returning to New York to open up a law practice with his brother Joe.27 Nahem’s ambivalence about his pro baseball career was tested when, after spring training, the Dodgers assigned him to back to their AA level Nashville farm team instead of their top minor league franchise in Montreal. Nahem wasn’t eager to return there. “I would go to Nashville outright,” Nahem told the Times, “but I now go back there on option. I made good there once, and if I can’t advance in baseball there’s no point in my remaining in the game. I definitely will quit baseball if some other disposition of me is not made.”28

Instead, Nahem arranged to be optioned to another AA level team, the Louisville Colonels, a Red Sox farm team in the American Association (where he was 3-5 with a 4.43 ERA).29 Even though he was playing for a team affiliated with the Red Sox, baseball’s reserve clause guaranteed that he remained the Dodgers’ property.

Whether or not Nahem’s resistance played a role, in June 1940 the Dodgers traded him (and three other players, along with $100,000) to the St. Louis Cardinals organization in a deal that sent star outfielder Joe Medwick to Brooklyn.30 The Cardinals assigned Nahem to their Texas League team, the Houston Buffaloes. During the second half of the season, Nahem pitched in 15 games for Houston (10 of them complete games) and posted an 8-6 won-loss record with a league-leading 1.64 ERA in 104 innings. Nahem’s pitching led Houston to the Texas League championship.31

The Cardinals brought Nahem up to the big league club the following season. They paid him $3,20032 — about $55,000 in today’s dollars. Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey had a “heart to heart” talk with Nahem that helped restore his confidence. According to Nahem, Rickey told him that “he had faith in me. What a psychologist he is! He said I was his boy, and he was picking me to make good. He told me I would pitch well the rest of the season, and darned if I didn’t.”33

Nahem recalled that when he joined the Cardinals in 1941, “I got a new concept of pitching” by watching his teammate Lon Warneke, an outstanding veteran. “I saw that it wasn’t like how I pitched them: High, low, inside, outside. He threw low and inside, high and outside. He threw inside and he threw outside. This farmer had a theory of pitching far more complicated than me, a law school graduate and bar-passer first crack. And his theory was really fascinating. Balance is everything in hitting, and if you can get the guy just a tip off balance, that really does something.”34

Discussing Nahem, Dodger outfielder Roy Cullenbine told the Brooklyn Eagle: “With that sidearm delivery of his, he fools you. His fastball is on top of the plate before you think he’s let go of the ball. Besides he’s big and with that sidearm motion he somehow manages to fire the ball at you with his uniform for a background. He’s tough.”35 Cardinals catcher Gus Mancuso told the Sporting News: “Nahem is not a speed-ball pitcher like these others, but he has a better all-round variety of stuff, and fine control. He can pitch to spots, and he is smart. His slider is a real humdinger.”36 Nahem credited Mancuso with being a big help. “I owe my steadiness and confidence to him,” Nahem told the Brooklyn Eagle.37

In his first starting assignment for the Cardinals, on April 23, 1941, Nahem showed great promise. He pitched a three-hitter, beating the Pittsburgh Pirates 3 to 1, striking out three and giving up only one walk. The Times called it “the Redbirds’ best hurling performance of the season.”38

That victory was “the greatest game I ever pitched in my whole career,” Nahem recalled many years later. “Tell me about heaven.”39 Explaining his accomplishment, Nahem said that the Cardinals had five rookie pitchers competing for two slots on the roster. “There’s something in the blood that inspired me in certain moments.”40

A week later, on April 30, Nahem won his second game in a row, over the New York Giants.41

On May 30, against the Cincinnati Reds, Nahem gave up only seven hits and two runs in nine innings, but after nine innings the score was tied 2-2 and manager Billy Southworth replaced Nahem with reliever Ira Hutchinson, who gave up a run in the 13th inning and took the loss.42 On July 5, he faced the Reds again. He pitched a complete game, giving up only six hits and two runs (one of them unearned), but he lost to the Reds’ ace Johnny Vander Meer, who allowed the Cardinals only one run.43

Against the Giants at the Polo Grounds on June 7, Nahem gave up three runs in the first two innings before being removed for a reliever. As the Times reported, “Sam Nahem, the Brooklyn barrister, was chased back to his law books in less than two rounds.”44

During the 1941 season, Nahem started eight games and relieved in 18. He won five games before losing two. He pitched 81 2/3 innings and registered a 2.98 ERA.

Despite this excellent performance, in August the Cardinals shipped Nahem to their AA minor league team in Columbus, Ohio. Again, Nahem voiced his objections to being sent to the minors. “I am not reporting [to Columbus],” he told the Columbus team president Al Banister, according to a newspaper story. But he soon “cooled off,” the paper reported. “realizing his career was at stake.”45 He pitched five games at Columbus, went 0-2, and had a disastrous 9.41 ERA.

On February 19, 1942, the Cardinals sold Nahem to the Phillies. That season he made 35 appearances for the Phillies, posting a 1-3 won-loss record and a 4.94 ERA. After the season was over, Nahem joined the military. It looked like his pro baseball career was over, but he would have a brief encore in 1948.

During his 11 years playing pro ball — interrupted by World War II and several seasons with a semipro team — Nahem spent more time in the minors than in the majors. He had a 51-44 record in the minors, including his first two years in Allentown and Jeanerette, where he had a 7-10 record under his alias, “Sam Nichols.”

Nahem described the minors as “hot dusty bush leagues” characterized by “long night bus travel, small crowds, crummy food, small time love affairs.” He dealt with the boredom and isolation by reading. “I read my way through those years. What does one do in Columbus, Ohio for the summer? The complete works of Honoré de Balzac. What about Jeanerette, Louisiana? Of course, the complete works of Theodore Dreiser.”46

Nahem would sometimes bring his books into the dugout. He’d quote Shakespeare and Guy de Maupassant in the middle of conversations. News stories about Nahem frequently emphasized his education, legal training, and erudition as well as his glasses.

After he was assigned to the Montreal Royals, one newspaper reported: “Montreal fans will find Sam Nahem, one of the Royals’ new pitchers, unusually interesting. He speaks French.”47 During spring training in 1940, an Associated Press reporter wrote: “Sam wears spectacles and talks less like a ballplayer than any diamond star this reporter knows. For reading material Nahem does not devote his time to pulp magazines — the Westerns, Adventure stories and whatnot — but goes for the realistic Russians, Dostoievski, Gorki, Chekov, and Tolstoi.” 48 Nahem clearly enjoyed his reputation as a highbrow hurler, telling the reporter: “I am a great believer in psychology and I admire the Russian outlook on life. On those days when my pitching has been horrible I lost myself in the Russian classics. I read much more when things are going bad for me than when I’m winning.”

But Nahem insisted that “My heart is wrapped up in making good in the majors. Of course, if I don’t, I’ll always have something to fall back on and even if I make good in the big show I can’t last forever and when I’m washed up my law will be good to fall back on.”49

Another Associated Press story the next year, when Nahem was trying to make the Cardinals’ roster, began: “Bespectacled Sam Nahem is a scholarly gent” and “a full-fledged attorney who can spiel 50-cent words in several languages and likes nothing better than a good argument with a rival batsman or on the relative importance of environment and heredity.”50 Nahem’s “[b]lack hair curling back over his high forehead gives him a professorial air, accentuated by the glasses he wears,” wrote the Brooklyn Eagle’s respected sports columnist Tommy Holmes, adding that with Nahem’s law degree from St. John’s, “the Dodgers have actually come up with a clubhouse lawyer.”51 Throughout Nahem’s career, newspapers routinely referred to his bald head. He took it all in stride. “Euphemistically, I could say I had hair, but euphemistically,” he once said.52

Though better-educated than most other players, Nahem was gregarious and extroverted, with a boisterous sense of humor, which made him popular with his teammates. But occasionally Nahem’s background impeded his relationships with other players. He once recalled:

“Andy Seminick [the Phillies’ catcher] really put me in my place once. He once said to me: ‘Sam, we all know that you went to college and that you’re a lawyer from New York. For heaven’s sakes, Sam, I come from a coal mining family.’ Then I realized that I had a condescending attitude toward them. It was arrogant of me. That wasn’t right because everybody is interesting in their own way and I hadn’t been pursuing that. So I was well chastised.” 53

“It was almost detrimental to him at that age. He was almost too bookish for the jocks he was around,” explained his son Ivan. “He might have gone further [in baseball] if it weren’t for his bookishness, but that’s who he was.” “I remember my dad said once he couldn’t understand James Joyce, and that was inconceivable to me. He was so well-read,” Ivan told a reporter.54

Nahem once recalled that, “I wasn’t a natural woman-hunter, and most players, even the successfully married ones, were skirt-chasers, they really were. I wasn’t too happy at that. [But] the class of women in the big leagues was higher than in the minor leagues. That was another reason to aspire to the big leagues.”55

Few of Nahem’s minor league teammates had ever met a New Yorker before. Someone gave him the nickname “Subway Sam,” which lasted throughout his baseball career.

Nahem enjoyed the physical and psychological aspects of being a good athlete, but, he recalled, “when I became political and radicalized I tried to think of sports in political and social terms.”56

Nahem had to deal with anti-Semitism among his teammates and other players. “I was aware I was a Jewish player and different from them. There were very few Jewish players at the time,” Nahem said. (There were 10 Jews on major league rosters in 1938, Nahem’s rookie year.) “I don’t blame the other players at all. Many of them came from where they probably had never met a Jewish person. You know, they subscribed to that anti-Semitism that was latent throughout the country. I fought it whenever I appeared…Much of it was implicit: Jews and money, Jews and selfishness.” To combat the stereotypes, “I especially made sure I tipped as much or more than any other player.”57

As a left-wing radical and a Jew who faced anti-Semitic bigotry, Nahem was sympathetic to the plight of African Americans.

“I was in a strange position,” he explained. “The majority of my fellow ballplayers, wherever I was, were very much against black ballplayers, and the reason was economic and very clear. They knew these guys had the ability to be up there and they knew their jobs were threatened directly and they very, very vehemently did all sorts of things to discourage black ballplayers.”58 His views were particularly selfless, because as a marginal player he was more likely than a real star to be replaced by a black pitcher if major league baseball ended its ban on black players.

Nahem talked to some of his teammates to encourage them to be more open-minded. “I did my political work there,” he told an interviewer years later. “I would take one guy aside if I thought he was amiable in that respect and talk to him, man to man, about the subject. I felt that was the way I could be most effective.”59

“That’s why he was so political,” his daughter Joanne explained. “He believed that people deserved more, so he had a great faith in humanity.”60

It is not surprising that Nahem was attracted to the Communist Party (CP).61 From the 1920s through the 1940s, the CP — although never even approaching 100,000 members — had a disproportionate influence in progressive and liberal circles. It attracted many idealistic Americans — including many Jews and African Americans — who were concerned about economic and racial injustice. In the U.S., the CP took strong stands for unions and women’s equality and against racism, anti-Semitism, and emerging fascism in Europe. It sent organizers to the Jim Crow South to organize sharecroppers and tenant farmers and was active in campaigns against lynching, police brutality, and Jim Crow laws. The CP led campaigns to stop landlords from evicting tenants and to push for unemployment benefits. In Harlem, it helped launch the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign, urging consumers to boycott stores that refused to hire African-American employees.62

The cause of baseball’s color line was a natural for the Communist Party. It was no accident that Lester Rodney, sports editor of the CP-sponsored newspaper, the Daily Worker, was one of the leading figures in the effort to integrate baseball. Beginning in the 1930s, the CP, along with the Negro press, civil rights groups, progressive white activists, and radical politicians waged a sustained campaign against baseball’s Jim Crow system. They believed that if they could push baseball to dismantle its color line, they could make inroads in other facets of American society. In 1938, the CP-led American Youth Congress passed a resolution censuring the major leagues for its exclusion of black players. In 1939, New York State Sen. Charles Perry, who represented Harlem, introduced a resolution that condemned baseball for discriminating against black ballplayers. In 1940 leftist sports editors from college newspapers in New York adopted a similar resolution. Black sportswriters — particularly Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier and Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American — made baseball part of a larger crusade to confront Jim Crow laws. After the U.S. entered World War II in 1941 Negro papers enthusiastically supported the “Double V” campaign — victory over fascism overseas and over racism at home.

For several years, left-wing unions marched in May Day parades with “End Jim Crow in Baseball” signs. On July 7, 1940, the Trade Union Athletic Association, comprised of 30 left-wing unions, held an “End Jim Crow in Baseball” demonstration at the New York World’s Fair. Progressive unions and civil rights groups picketed outside Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds, and Ebbets Field in New York City, and Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field in Chicago to demand an end to baseball’s color line. In June 1942, several major unions — including the United Auto Workers and the National Maritime Union, as well as the New York Industrial Union Council of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) — sent resolutions to Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis demanding an end to baseball segregation. That December, ten leaders of the CIO, the progressive union federation, went to the winter meetings of baseball’s executives at Chicago’s Ambassador East Hotel to demand that major league baseball recruit black players, but Landis refused to meet with them.63 In December 1943, the publisher of the Chicago Defender, a leading black newspaper, arrange for the well-known actor, singer and activist Paul Robeson to head a delegation (that included Wendell Smith) to meet with Landis and major league owners at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City. Robeson told them: ”The time has come when you must change your attitude toward Negroes. . . . Because baseball is a national game, it is up to baseball to see that discrimination does not become an American pattern. And it should do this this year.”64

It is unlikely that Nahem actively participated in many of these protests, since he was playing pro baseball and attending law school or working during the off-season. He was probably the only Communist Party member on a professional baseball roster, but none of the profiles about him during his playing days referred to his left-wing politics. It is possible that he didn’t discuss his political ideas with reporters, or perhaps they liked him enough to keep his controversial views out of their stories. As Nahem recalled, “The sportswriters liked me a lot, since no matter what, I always had some cliché I could twist around for them.”65 He was well-educated, articulate and quotable, and had a quick wit. For example, when a sportswriter asked him about his lackluster performance during spring training in 1940, Nahem replied, “I am now in the egregiously anonymous position of pitching batting practice to the batting practice pitchers.”66 When a radio interviewer asked him how to say “Merry Christmas” in Arabic, Nahem responded with the name of a Syrian cheese omelet.67

During World War II, the American military ran a robust baseball program at home and overseas. President Franklin Roosevelt believed it would help soldiers stay in shape and boost the country’s morale. Many professional players were in the military, so the quality of play was often excellent. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the military expanded its baseball program while American troops remained in Europe. That year, over 200,000 American soldiers were playing baseball on military teams in France, Germany, Belgium, Austria and Britain.68

Many of the Negro Leagues’ finest ballplayers saw military service during the war, but like other African Americans they faced discrimination and humiliation as soldiers. Most black soldiers with baseball talent were confined to playing on all-black teams. When Jackie Robinson went out for the baseball team at Ft. Riley, Kansas, a white player told him that the officer in charge said, “I’ll break up the team before I’ll have a nigger on it.”69 Larry Doby, who would later become the first African American in the American League, was blocked from playing baseball for the all-white Great Lakes Navy team near Chicago. Monte Irvin, a Negro League standout who later starred for the New York Giants, recalled that, “When I was in the Army I took basic training in the South. I’d been asked to give up everything, including my life, to defend democracy. Yet when I went to town I had to ride in the back of a bus, or not at all on some buses.”70 A few African Americans played on racially integrated military teams in the South Pacific, but not in other military installations.71

Nahem entered the military in November 1942. He volunteered for the infantry and hoped to see combat in Europe to help defeat Nazism. But he spent his first two years at Fort Totten in New York. While stationed there, however, he pitched for the Anti-Aircraft Redlegs of the Eastern Defense Command. The team was part of the Sunset League comprised of teams from military bases in the New England area. In 1943 he set a league record with a 0.85 earned run average. He also finished second in hitting with a .400 batting average and played every defensive position except catcher.72 These military games were important enough to be reported in the New York Times and other local papers.

While stationed at Fort Totten, Nahem pitched in several exhibition games with current and former major leaguers serving in the military. In June 1944 he pitched in the Polo Grounds in a game to raise money for War Bonds before 30,000 spectators.73 On September 5, 1944, his Ft. Totten team beat the major league Philadelphia Athletics by a 9-5 margin in an exhibition game. Nahem not only pitched six innings, giving up only two runs and five hits, but also slugged two homers, accounting for seven of his team’s runs.74

Sent overseas in late 1944, Nahem served with an anti-aircraft artillery division. From his base in Rheims, he was assigned to run two baseball leagues for servicemen in France, while also managing and pitching for his own team, the Overseas Invasion Service Expedition (OISE) All-Stars, which represented the army command in charge of communication and logistics in the liberated areas. The team was comprised mainly of semi-pro, college, and ex-minor-league players.75 Besides Nahem, only one other OISE player had major league experience — Russ Bauers, who had compiled a 29-29 won-loss record with the Pirates between 1936 and 1941.76 When Nahem wasn’t pitching, he played first base.77

Defying the military establishment and baseball tradition, Nahem insisted on having African Americans on his team. One was Willard Brown, an outfielder with the Kansas City Monarchs and one of the Negro Leagues’ most feared sluggers.78 The other was Leon Day, a star pitcher for the Negro League’s Newark Eagles.79

Each branch of the military and different divisions had their own teams. The competition among the American teams in Europe was fierce. Nahem’s OISE team won 17 games and lost only one, attracting as many as 10,000 fans to their games.80 Nahem beat the Navy All-Stars in England, then pitcher Bob Keane beat the same team in France, to advance the OISE team to the semi-finals.81 On September 1, in the semi-final round, Nahem pitched the OISE All-Stars into the European champion series by beating the 66th Division team, representing the Sixteenth Corps, by a 5-4 margin in 11innings. Nahem also got four hits in five at-bats.82

The other team that reached the finals was the 71st Infantry Red Circlers, representing the 3rd Army, commanded by General George Patton and named for their red circles shoulder patches. One of Patton’s top officers assigned St. Louis Cardinals All-Star outfielder Harry Walker to assemble a team — the Red Circlers — to represent the 3rd Army. Given Patton’s clout, it probably wasn’t difficult for Walker to arrange for eight other major leaguers to be transferred to his team. Besides Walker, the Red Circlers included Cincinnati Reds’ 6-foot-6 inch sidearm pitcher Ewell “the Whip” Blackwell, 83 Reds second baseman Benny Zientara, Pirates outfielders Johnny Wyrostek and Maurice Van Robays, Cardinals catcher Herb Bremer, Cardinals pitcher Al Brazle, Pirates pitcher Ken Heintzelman, and Giants pitcher Ken Trinkle.

Against the powerful Red Circlers, few people gave Nahem’s OISE All-Stars much of a chance to win the European Theater of Operations (ETO) championship, known as the G.I. World Series.It took place in September, a few months after the U.S. and the Allies had defeated Germany.

The OISE All-Stars and the Red Circlers played the first two games in Nuremberg, Germany, in the same stadium where Hitler had addressed Nazi Party rallies. Allied bombing had destroyed the city but somehow spared the stadium. The U.S. Army laid out a baseball diamond and renamed the stadium Soldiers Field. 84

On September 2, 1945, Blackwell pitched the Red Circlers to a 9-2 victory in the first game of the best-of-five series in front of 50,000 fans, most of them American soldiers.85 In the second game, Day held Patton’s army all-star team to one run. Brown drove in the OISE’s team first run, and then Nahem (who was playing first base) doubled in the seventh inning to knock in the go-ahead run. OISE won the game by a 2-1 margin. Day struck out 10 batters, allowed four hits and walked only two hitters.86

The two teams flew to OISE’s home field in Rheims for the next two games. The OISE team won the third game, as the Times reported, “behind the brilliant pitching of S/Sgt Sam Nahem,” who outdueled Blackwell to win 2-1, scattering four hits and striking out six batters.87 In the fourth game, the 3rd Army’s Bill Ayers, who had pitched in the minor leagues since 1937, shut out the OISE squad, beating Day by a 5-0 margin.88

The teams returned to Nuremberg for the deciding game on September 8, 1945. Nahem started for the OISE team in front of over 50,000 spectators. After the Red Circlers scored a run and then loaded the bases with one out in the fourth inning, Nahem took himself out and brought in Bob Keane, who got out of the inning without allowing any more runs and completed the game. The OISE team won the game 2-1. 89

A Jewish Communist and two Negro Leaguers had helped OISE win the GI World Series. The Sporting News adorned its report on the final game with a photo of Nahem.90

Back in France, Brigadier Gen. Charles Thrasher organized a parade and a banquet dinner, with steaks and champagne, for the OISE All-Stars. As historian Robert Weintraub noted: “Day and Brown, who would not be allowed to eat with their teammates in many major-league towns, celebrated alongside their fellow soldiers.”91

Having won the ETO World Series, the OISE All-Stars traveled to Italy to play the Mediterranean Theater champions, the 92nd Infantry Division Buffaloes, an all-black division. Several major league players on the 5th Army’s Red Circles — Blackwell, Heintzelman, Van Robays, Zientara, Garland Lawing, and Walker — got themselves added to the OISE All Stars roster, which meant that some of OISE’s semipro, college, and minor league players were left behind.92 The OISE All-Stars beat the Buffaloes in three straight games, with Day, Keane, and Blackwell gaining the wins. Then Day switched to the all-black team and beat Blackwell and his former OISE teammates, 8-0, in Nice, France.93

One of the intriguing aspects of this episode is that, despite the fact that both major league baseball and the American military were racially segregated, no major newspaper even mentioned the historic presence of two African Americans on the OISE roster. If there were any protests among the white players, or among the fans — or if any of the 71st Division’s officers raised objections to having African American players on the opposing team — they were ignored by reporters. For example, an Associated Press story about the fourth game simply referred to “pitcher Leon Day of Newark.” 94

In October 1945, a month after Nahem pitched his integrated team to victory in the military championship series in Europe, Branch Rickey announced that Robinson had signed a contract with the Dodgers.

Nahem played high-caliber baseball during his almost four year service in the military. He was only 30 when he was discharged from military service. Major league teams were supposed to give their military veterans a chance to resume playing, but when Nahem came back from the war in early 1946, he did not return to the Phillies. Under the reserve clause, he was still the Phillies’ property unless they formally released him, but there is no record that they did so. Whether the team let him know he wasn’t wanted or whether Nahem decided to give up on the majors and finally start practicing law is not known.

After returning to New York, Nahem worked briefly as a law clerk and intermittently in his family’s export-import business. He played baseball on weekends for a top-flight semi-pro team, the Brooklyn Bushwicks, who were on a par with, and occasionally even better than, the best minor league teams.95 The Times and other New York papers regularly covered the Bushwicks’ games and Nahem’s exploits on the mound. In August he pitched an 11-inning no-hitter against the Seaport Gulls, giving up only two walks and facing only 35 batters, winning by a 1-0 score. It was the first no-hitter by a Bushwicks pitcher in ten years. Nahem’s performance with the Bushwicks revealed that he was still an excellent pitcher, so his absence from a major league roster remains a mystery.96

In June 1946, a columnist for the Nashville Tennessean reported that while pitching on Sundays for the Bushwicks, and practicing law during the week, Nahem was also a candidate for the New York State Assembly from a Brooklyn district. The Sporting News and the Chicago Tribune both published brief notes reporting Nahem’s candidacy, too.97 But an article in the Brooklyn Eagle the following month reported that Nahem “has given up any idea of running for the State Assembly.”98 In August, however, the Sporting News wrote that Nahem was thinking of running for Congress from Brooklyn.99 Little is known about this aspect of Nahem’s life and there’s no evidence that he actually ran for any public office. His oldest son Ivan wasn’t aware that Nahem had ever run, or considered running.100

Nahem couldn’t have mounted much of a campaign because by October 1946, he was with the Bushwicks in Caracas, Venezuela, representing the United States in the Inter-American Tournament. Against teams representing Mexico, Venezuela, and Cuba, Nahem won three and lost one. He clinched the tournament title for the Bushwicks with a 7-6 win over Cuba.

Nahem was back with the Bushwicks for the 1947 season. In June, he pitched the team to a 4-1 victory over the Homestead Grays of the Negro Leagues, striking out eight batters.101 In July he threw a six-hitter and struck out 10 hitters to beat the Memphis Red Sox, another Negro League team, by 7-2.102 On October 12, 1947, he pitched the Bushwicks to a 3-0 victory with a one-hitter against a barnstorming team, the World Series All-Stars, that included major leaguers Eddie Stanky, Phil Rizzuto, and Ralph Branca, who was the losing pitcher. It was Nahem’s 17th win that season.103 He eventually won 21 games in a row. During the 1946 and 1947 seasons, Nahem was 33-6 for the Bushwicks.104

During those two years, while still playing for the Bushwicks, Nahem also played for the Sunset Stars, a semipro team based in Newport, Rhode Island. The Stars played their games on Wednesday nights and Nahem — who had played in the same league in 1943 while stationed at Ft. Totten — was popular with the Rhode Island fans.105 The Stars played local Rhode Island teams as well as Negro League teams and barnstorming teams like the House of David.106 In a game in June 1946 against the Boston Colored Giants, Nahem pitched 12 innings and struck out 22 batters, only to lose 3-2.107 That year he played in 16 of the Stars’ 18 night games and struck out 193 hitters in 147 innings, posting a 1.81 earned run average.108

Nahem played winter ball with the Navegantes del Magallanes club of the Venezuelan Professional Baseball League. There he pitched 14 consecutive complete games in the 1946-47 season to set a league record that still stands today.

Nahem once explained that he made more money playing for the Bushwicks, the Sunset Stars, and the Venezuelan club in the same year than he made as major league pitcher.109

At the start of 1948, Nahem was still pitching with the Bushwicks. But by April, the Phillies beckoned again and he began another brief fling in the major leagues.110 On April 30, his first game that season in a Phillies uniform, he pitched two innings in relief against the Dodgers, allowing only one hit but walking five batters and giving up four runs.111

The Phillies were one of baseball’s most racist teams, known for verbal abuse toward Jackie Robinson in his rookie season the previous year. Manager Ben Chapman had gained notoriety for his vicious taunting of Robinson and was still managing the team during the first half of the 1948 season.112

Years later, Nahem recalled that “he [Chapman] left me in once to take a real beating. When you’re a racist you are also an anti-Semite. Some reporters asked him about it, whether he kept me in there for some reason other than the demands of the game. He denied that it was anti-Semitism.”113

“I was very much for Jackie Robinson and at one point I tried to counter some of this racist stuff openly,” Nahem recounted. “One of the southerners was fulminating in the clubhouse in a racist way and I made some halfway innocuous remark defending blacks coming in to baseball. Boy, he went into a real tantrum and really came down on me. So I decided I would not confront anyone openly. Your prestige on a ballclub depends on your won-loss record and your earned run average. I didn’t have that to back me up. I only had logic and decency and humanity. So after that I would just speak to some of the guys privately about racism in a mild way.”114

In one game, Nahem threw a pitch that almost hit Roy Campanella, the Dodgers’ African American rookie catcher.

“He had come up that year and had been thrown at a lot, although there was absolutely no reason why I would throw at him,” Nahem said. “A ball escaped me, which was not unusual, and went toward his head. He got up and gave me such a glare. I felt so badly about it I felt like yelling to him, ‘Roy, please, I really didn’t mean it. I belong to the NAACP.”115

Given his poor performance with the Phillies in 1942, and his disagreements with Chapman, it is surprising that the Phillies invited Nahem back. It is possible that Nahem’s friend Eddie Miller — an All-Star shortstop whom the Phillies acquired before the 1948 season — persuaded the team to give Nahem another chance.116 During that season Nahem went 3-3 for the Phillies, mostly in relief, on a sixth-place team that had its 16th straight losing season. He pitched his last major league game on September 11, 1948, giving up one hit and one run, and striking out two batters, in the ninth inning against the Boston Braves.117 A week later, the Phillies released him.118

During four seasons spread over ten years, Nahem pitched 224 innings in 90 major league games. Plagued with control problems, he struck out 101 batters but walked 127.119

Nahem took full advantage of his pitching repertoire. As noted, pitching exclusively overhand (mostly curves and fastballs) against left-handed batters and exclusively sidearm (mostly sliders and fastballs) against right-handed hitters was rare and perhaps unique.120 Not surprisingly, he performed better in righty-righty matchups (.232 during his major league career) than against lefty swingers (.307).121

Nahem was grateful for the friendships, experiences, and notoriety that his major league career provided. But looking back, he noted that he wasn’t very happy in his big league days. Part of it was a matter of lifestyle. “We traveled a lot; we didn’t have a stable place to stay.” Another part was his failure to live up to his expectations as a player. “One day I’d pitch OK in relief, the next day they hit the shit out of me. It’s hard to be happy in something you’re doing in just a mediocre way.”122

He once said: “I often wish that God had given me movement on my fastball, but he didn’t.”123 In another interview, he observed, “I had just-above-mediocre stuff. Just enough to flash at times.”124 He particularly regretted that, even as a big leaguer, he never received the mentoring that could have helped him improve his pitching. Long after he retired, he learned that coaches for opposing teams noticed that he tipped his pitches — he raised his arms higher during the windup when throwing a curve — but his own coaches had never spotted this flaw. “If I had some decent coaches, they would have spotted it, too,” Nahem said. 125

Looking back on his major league career, Nahem wistfully observed that “if I executed what I understand now, I could have been quite a decent pitcher. I had enough stuff to be a fairly good pitcher…I was a smart pitcher out there, but at the last second, I wouldn’t have confidence in my control, so I would forget to pitch high or low or outside and just try to get it over the plate.”126 In a revealing exchange, he once asked Phillies teammate Robin Roberts, a future Hall of Fame pitcher, if he was ever scared when he was on the mound. Roberts said he wasn’t. “That is what really pisses me off,” Nahem responded. “I’m scared stiff out there.”127

Despite his trepidation on the mound, Nahem kept his sense of humor intact. While with the Phillies, he was brought in as a reliever to face three of the Cardinals’ best hitters — Red Schoendienst, Enos Slaughter, and Stan Musial. He retired Schoendienst and then signaled Phillies’ first baseman Dick Sisler to come to the mound. As Roberts recalled: “We all saw Dick laughing while he trotted back to first. After the inning was over Dick said that Sam had told him, ‘I got the first guy, you want to try these next two?’”128

After leaving the Phillies, Nahem pitched briefly for the San Juan team in the Puerto Rican League at the end of 1948.129 Then he rejoined the Bushwicks for the 1949 season. He won seven games in a row by the end of June and finished the season with a 10-7 record.130 That season he still occasionally played for the Sunset Stars. He was so popular that the local paper, the Newport Mercury, published a story about his wedding. According to the June 10, 1949 edition, “After playing in the 13-inning game Wednesday which ran past midnight Nahem caught the 2:10 train at Providence and arrived in New York three hours before his wedding.”131 In August, Nahem’s Stars lost to the Boston Colored Giants, but he struck out seven batters and got three hits in five at bats.132 He pitched his final game for the Bushwicks in October, then hung up his spikes.

By the time Nahem ended his playing career, the Cold War was in full swing, casting a chill on American radicals, but he remained a committed leftist. Just as he had participated in radical causes during the 1930s, like raising money for the anti-fascists during the Spanish Civil War, Nahem continued his political activism. In 1949, at age 34, he married art student Elsie Hanson, whom he’d met at a Communist Party-sponsored concert and fundraiser.133 In 1950, his name appeared on a list of candidates running for the New York State Assembly from New York City as the candidate of the American Labor Party (ALP), a left-leaning group whose most prominent member was Congressman Vito Marcantonio.134 Perhaps the ALP thought that his fame as a former ballplayer would garner votes. Whether he actually campaigned for the seat isn’t known, but he didn’t win. In 1951, according to his son Ivan, he participated in protests against the controversial conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were sentenced to death for being Soviet spies.

During that period, he worked briefly as a law clerk in New York. Nahem told an interviewer that he wanted to practice civil liberties law, but that the jobs in that field were dominated by graduates of Ivy League law schools, stiff competition for a graduate of St. John’s School of Law.135 During the Cold War, even organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union, much less mainstream law firms, were wary of hiring lawyers with left-wing views, especially Communists.

“He went into the law thinking he’d be Clarence Darrow,” his son Ivan explained, “but he was soon disillusioned and bored, and quit.” He worked briefly for his family’s import business,136 as a door-to-door salesman, and then as a longshoreman unloading banana boats on the New York docks.

The FBI kept tabs on Nahem, as it did with many leftists during the 1950s Red Scare. FBI agents would show up at his workplaces and tell his bosses that he was a Communist. He lost several jobs as a result. It isn’t clear when their surveillance of him began or ended, but as late as 1961 — when he had moved to California and was working in a chemical fertilizer plant and was a union leader — the FBI was still keeping a file on him.137

To escape the Cold War witch-hunting, and to start life anew, Nahem, his wife Elsie, and their two children (Ivan, born in 1950, and Joanne, born in 1953) moved to the San Francisco area in 1955. They settled first in Mill Valley, and then blue-collar Richmond in the East Bay. A third child, Andrew, was born in 1961. Elsie found work as a commercial artist.

Nahem got a job at the Chevron fertilizer plant in Richmond, owned by the giant Standard Oil Corporation. During most of his 25 years at Chevron (more than twice the time he spent playing professional baseball), he worked a grueling schedule — two weeks on midnight shift, two weeks on day shift, then two weeks on swing shift.

By 1957, like many other Communists, Nahem and Elsie became disillusioned with Russia’s stifling of democracy in Eastern Europe and within its own borders, and left the Communist Party. But he remained an activist. He served as head of the local safety committee for the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers union at the Richmond plant. Nahem was often offered management positions, but he refused to take them, preferring to remain loyal to his coworkers and his union. He ended as head operator, the best job he could get and still stay in the union.

Nahem liked to relax by watching football and baseball on television and passing on his enthusiasm for sports to his kids. “When I was a kid,” son Ivan recalled, “some of my best times with him were playing catch.”

While still working at Chevron, Nahem moved to nearby Berkeley in 1964. That year the Free Speech Movement started on the nearby University of California-Berkeley campus and the town became a hotbed of radicalism. Despite his grueling work schedule, Nahem immersed himself in the new wave of activism. He took his children to civil rights and anti-war demonstrations. His son Ivan recalled Nahem hosting lots of dinner parties where the talk was all about politics. In 1969, Nahem helped lead a strike among Chevron workers that attracted support from the Berkeley campus radicals.

After he retired from Chevron in 1980, he volunteered at the University Art Museum and frequented a Berkeley coffee shop, where he loved engaging in political discussions with local students, artists, and activists. After George Bush defeated Al Gore for president in 2000, Nahem told a nephew: “For much of my adult life I’ve seen the working class vote against their long-term interests. This is the first time I’ve seen them vote against their short-term interests.”138

Sam and his brother Joe remained close until Joe’s death in 1992. “They were hilarious together at parties, reminiscent sometimes of their heroes the Marx Brothers,” recalled Joe’s daughter Beladee.139 At a dinner party in the 1990s, Nahem told his fellow diners, “Many people used to compare me with Sandy Koufax. They would say ‘You were no Koufax’. I told them thanks for putting me and Koufax in the same sentence.”140

Elsie Nahem died of cancer in 1974. Sam never remarried but he had a long-term relationship with Nancy Shafsky. He died on April 19, 2004 in Berkeley at age 88.141 Nahem was survived by his three children and three grandchildren. His older sister Victoria and her husband Abraham Silvera had a son, Aaron Albert (Al) Silvera, who played in 14 games for the Cincinnati Redlegs in 1955 and 1956, making Nahem the uncle of another major leaguer.

Nahem was proud of his accomplishments on the diamond, which gave him a lifetime of memories and stories that he shared with his friends and family.

“I loved the feeling of a baseball in my hand. And the perfect meeting of the bat with the ball was the nearest thing to an orgasm,” he wrote in his autobiographical essay during his later years. “In both you are disembodied, weightless.”142

Although he often talked about his days as a major league pitcher, he rarely discussed the accomplishment that best combined his athletic talent and his political views — his role in integrating military baseball.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Ivan Nahem, Beladee Nahem Griffiths, Joel Isaacs, David Nemec, Bill Nowlin, Robert Elias, Mike Lynch, Robert Weintraub, Lee Lowenfish, Shawn Hennessy, John and Dan Wormhoudt, Isaac Silvera, Colleen Bradley-Sanders (Brooklyn College archivist), and Cassidy Lent (Baseball Hall of Fame reference librarian) for their help.

A version of this paper was originally presented at the Thirtieth Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2018.

This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Warren Corbett and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Interviews

Ivan Nahem (Sam’s son), January 3, 2017.

Beladee Nahem Griffiths (Sam’s niece), January 7 and 14, 2018.

Correspondence

Email from Nahem’s cousin Joel Isaacs, January 9, 2017.

Email from David Nemec, December 12, 2017.

Email from Robert Weintraub, December 27, 2017.

Email from Beladee Nahem Griffiths, January 9, 2018.

Email from Colleen Bradley-Sanders, May 25, 2018.

Email from Sam Bernstein, June 5, 2018.

Email from Dan Wormhoudt, June 23, 2018.

Unpublished essay

“The Autobiography of Samuel Ralph Nahem” (15 pages) provided by Ivan Nahem (hereafter “The Autobiography”).

Books

Boxerman, Burton, and Benita Boxerman, Jews and Baseball, Vol. 1 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007).

Ephross, Peter, with Martin Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words: Oral Histories of 23 Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012).

Horvitz, Peter S., and Joachim Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball (New York: SPI Books, 2001).

Klima, John. The Game Must Go On: Hank Greenberg, Pete Gray, and the Great Days of Baseball on the Home Front in WWII (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015).

Mead, William B. Baseball Goes to War (Washington: Farragut Publishing Co., 1985).

Roberts, Robin, and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000).

Weintraub, Robert. The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Little Brown & Co., 2013).

Newspaper articles

Eskenazi, Joe. “Artful Dodger: Baseball’s ‘Subway’ Sam Strikes Out Batters, and with the Ladies’ Too,” J Weekly, October 23, 2003 jweekly.com/article/full/20827/artful-dodger.

Eskenazi, Joe.“ ‘Subway’ Sam Nahem, Ballplayer and Union Man, Dies at 88,” J Weekly, April 23, 2004. jweekly.com/article/full/22430/-subway-sam-nahem-ballplayer-and-union-man-dies-at-88.

Isaacs, Stan. “Major Leaguer Sam Nahem Was One-of-a-Kind,” TheColumnists.com, 2004.

Kelley, Brent. “Sam Nahem: The Pitching Attorney,” Sports Collectors Digest, December 23, 1994.

Miller, Stephen. “Subway Sam Nahem, 88, Pitcher and Briefly a Dodger,” New York Sun, May 4, 2004.

Parrott, Harold. “Nahem Fortunes Curved Up and His Pitches Over Plate On Rickey Biblical Quotation and ‘Psychology Séance,’” The Sporting News, May 22, 1941.

Yollin, Patricia. “Samuel Ralph Nahem — Big-Leaguer in Many Ways,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 3, 2004. sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Samuel-Ralph-Nahem-big-leaguer-in-many-ways-2762291.php.

Notes

1 Sam Nahem, “The Autobiography of Samuel Ralph Nahem” (15 pages), provided by Ivan Nahem (hereafter “The Autobiography”), undated.

2 “The Autobiography.”

3 Harold Parrott, “Nahem Fortunes Curved Up and His Pitches Over Plate on Rickey Biblical Quotation and ‘Psychology Séance,’” The Sporting News, May 22, 1941.

4 ncdrisc.org/data-downloads-height.html.

5 “The Autobiography.”

6 “The Autobiography.”

7 Parrott, “Nahem Fortunes Curved Up.”

8 “The Autobiography.” Nahem also tells this story in an interview for Ephross with Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words; in Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000); and in an interview in Brent Kelley, “Sam Nahem: The Pitching Attorney,” Sports Collectors Digest, December 23, 1994. Nahem was wrong about Mungo’s origins. He was from South Carolina, not Oklahoma.

9 “The Autobiography.”

10 During his playing career, many news stories about Nahem reported that he graduated from Brooklyn College, but research by Brooklyn College archivist Colleen Bradley-Sanders indicates that he left Brooklyn College in 1935 after his sophomore year. Email from Colleen Bradley-Sanders, May 25, 2018.

11 Burton Boxerman and Benita Boxerman, Jews and Baseball, Vol. 1 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007); Peter S. Horvitz and Joachim Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball (New York: SPI Books, 2001).

12 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=bab1fb39

13 “Brooks Drop Nichols,” Elmira (NY) Star-Gazette, June 16, 1936.

14 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=c4f629c6; “Blues Even Series,” Alexandria (LA) Town Talk, August 29, 1936; “Dynamite Dunn Sets Evangeline Pace with Willow,” Alexandria (LA) Town Talk, September 12, 1936.

15 “Brooks Blast Out 17 Blows to Beat Binghampton, 13-8,” Reading Times, July 18, 1935.

16 “Along Sport Lane,” Hazleton (PA) Standard-Sentinel, May 14, 1936; “Inside Stuff,” Allentown (PA) Morning Call, June 15, 1936; “Brooks Drop Nichols,” Elmira (NY) Star-Gazette, June 16, 1936.

17 “Allentown Brooks Hope to Get into Initial Spring Drill This Afternoon,” Allentown Call, April 7, 1936. It is not clear why the reporter used the first name “Hassel” in referring to Nahem. Nahem’s son Ivan has never heard that name used to refer to his father.

18“Priest, Pitcher, Cop Pass Tests for Bar,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 23, 1938; George Kirksey (Associated Press), “Dodger Fans May Demand Nahem Plead Own Defense,” Nashville Tennessean, March 7, 1940. Nahem also took courses at Brooklyn College during the Fall 1938 semester. He earned a grade in one class and an incomplete in the other course. Interview with Brooklyn College archivist Colleen Bradley-Sanders, January 23, 2018. He may have used the course credit toward his law degree at St. John’s University.

19 baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=nahem-001sam.

20 The Times was mistaken. Nahem was a right-handed pitcher, not a “southpaw,” baseball slang for left-handed.

21 baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHI/PHI193810021.shtml.

22 Peter Ephross with Martin Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words: Oral Histories of 23 Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012). For Grimes’s influence on Nahem, see also Robert B. Cooke, “Nahem, Lawyer — Plea to Dodgers,” New York Herald Tribune, February 10, 1940.

23 “14 From the Minors Recalled by Dodgers,” New York Times, August 29, 1939; “Series Lead to Nashville,” New York Times, October 2, 1939.

24 Roscoe McGowen, “Mungo of Dodgers Bent on Comeback,” New York Times, February 18, 1940.

25 Stanley Frank, New York Post, February 22, 1940. This article is from the Nahem file in the Baseball Hall of Fame archives. The headline is missing.

26 Roscoe McGowen, “19 Dodgers Face Nahem in Inning,” New York Times, March 5, 1940.

27 Kirksey, “Dodger Fans May Demand Nahem Plead Own Defense.”

28 Roscoe McGowen, “Dodgers Abided by Landis Hints, Not ‘Orders,’ MacPhail Explains,” New York Times, May 29, 1940.

29“Cards Option Three Players,” New York Times, July 2, 1940.

30 Kingsley Childs, “Star Outfielder Traded by Cards,” New York Times, June 13, 1940.

31 “Exports Face Buffs Today,” Brownsville (Texas) Herald, September 17, 1940; “Vols Rest for First Game of Dixie Series,” Jackson (Tennessee) Sun, September 24, 1940; “Cards and Browns Draw 4 Texas Aces,” The Sporting News, October 31, 1940; “Nashville Takes Lead Over Buffs in Dixie Series,” Waco News-Tribune, September 26, 1940; “Volunteers Take Shutout Triumph Over Bison Team,” Waco News-Tribune, September 30, 1940. Harold Parrott, “Nahem Fortunes Curved Up and His Pitches Over Plate on Rickey Biblical Quotation and ‘Psychology Séance,’” The Sporting News, May 22, 1941.

32 Ephross with Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words.

33 Parrott, “Nahem Fortunes Curved Up.”

34 Ephross with Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words. In 1941 Nahem told the New York Daily News that Warneke helped him improve his slider. See also Joe Trimble, “Cards Keep Nahem as Starting Hurler,” New York Daily News, May 14, 1941.

35 Tommy Holmes, “Nahem in Strong Bid for Dodger Pitching Job,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 22, 1940.

36 Parrott, “Nahem Fortunes Curved Up.”

37 James Murphy, “Sammy Eyes Series Dough,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 11, 1941.

38 “Nahem, Cardinals, Halts Pirates, 3-1,” New York Times, April 24, 1941. Box score: baseball-reference.com/boxes/SLN/SLN194104230.shtml.

39 “The Autobiography.”

40 Ephross with Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words.

41 “Nahem Sets Back Terrymen by 6-4,” New York Times, May 1, 1941. Box score: baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1194104300.shtml.

42 baseball-reference.com/boxes/SLN/SLN194105302.shtml.

43 “Vander Meer Tops Cards for Reds, 2-1; Stars on Mound and in Field — St. Louis Is Turned Back Fourth Straight Time; Victors Score in First; Nahem Suffers Only Defeat in Six Starts,” New York Times, July 5, 1942. Box score: retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1941/B07050CIN1941.htm

44 John Drebinger, “19 Hits by St. Louis Crush Giants, 11-3,” New York Times, June 8, 1941

45 This information is from an article in the Nahem file in the Baseball Hall of Fame archives dated August 21, 1941. The name of the newspaper and headline are missing.

46 Nahem, “The Autobiography.”

47 This article is from the Nahem file in the Baseball Hall of Fame archives. It is dated April 6, 1939, but the name of the newspaper and the headline is missing.

48 Harry Grayson, “Russo Hurls One-Hitter as Yanks Extend Hit Streaks,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), June 27, 1941.

49 George Kirksey (Associated Press), “Dodger Fans May Demand Nahem Plead Own Defense,” Nashville Tennessean, May 7, 1940.

50 James Lawson (Associated Press), “Subway Sam, the Nahem Man, Is Poison to Cardinal Foes,” Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times, June 2, 1941.

51 Tommy Holmes, “Nahem in Strong Bid for Dodger Pitching Job,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 22, 1940.

52 Joe Eskenazi, “Artful Dodger: Baseball’s ‘Subway’ Sam strikes out batters, and with the ladies’ too,” J Weekly, October 23, 2003 jweekly.com/article/full/20827/artful-dodger.

53 Roberts and Rogers, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant, 147.

54 Joe Eskenazi, “Subway Sam Nahem, Ballplayer and Union Man, Dies at 88,” J Weekly, April 23, 2004. jweekly.com/article/full/22430/-subway-sam-nahem-ballplayer-and-union-man-dies-at-88.

55 Eskenazi, “Artful Dodger.”

56 “The Autobiography.”

57 Eskenazi, “Artful Dodger.” Figures on the number of Jews in the majors for each year come from Jewish Baseball News: jewishbaseballnews.com/

58 Eskenazi, “Artful Dodger.” Eskenazi conducted the interview with Nahem for the book Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words by Ephross with Abramowitz. There are slight differences in the wording in the two interviews. Unless otherwise indicated, I’ve used quotes from Nahem in the Eskenazi article.

59 “Artful Dodger.”

60 Eskenazi, “‘Subway Sam Nahem.”

61 Nahem’s membership in the Communist Party was confirmed by his son, Ivan, his niece Beladee Griffiths, and his cousin Joel Isaacs; mentioned in several obituaries, and hinted at in Nahem’s unpublished “Autobiography.” Phone interviews with Ivan Nahem on January 3, 2017; and with Beladee Nahem Griffiths on January 7 and 14, 2018; email from Joel Isaacs, January 9, 2017; Email from Beladee Nahem Griffiths, January 9, 2018; Patricia Yollin, “Samuel Ralph Nahem — Big-Leaguer in Many Ways,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 3, 2004. sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Samuel-Ralph-Nahem-big-leaguer-in-many-ways-2762291.php; Stan Isaacs, “Major Leaguer Sam Nahem Was One-of-a-Kind,” The Columnists.com, 2004; Stephen Miller, “Subway Sam Nahem, 88, Pitcher and Briefly a Dodger,” New York Sun, May 4, 2004.

62 The Communist Party’s involvement in the civil-rights and labor movement, particularly during the Depression, are discussed in Hosea Hudson and Nell Irvin Painter, The Narrative of Hosea Hudson, His Life As a Negro Communist in the South (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1979); Robin Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Robert Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Caroline Press, 2003); August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981); Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004); and Mark Solomon, The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-36 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998).

63 The protest movement to integrate major-league baseball is discussed in Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983); Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Irwin Silber, Press Box Red: The Story of Lester Rodney, the Communist Who Helped Break the Color Line in American Sports (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003); Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); and Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1997).

64 Silber, Press Box Red.

65 “The Autobiography.”

66 “The Autobiography.”

67 Jennifer Felicia Abadi, A Fistful of Lentils: Syrian-Jewish Recipes from Grandma Fritzie’s Kitchen (Boston: Harvard Common Press, 2007).

68 Discussion of World War II military baseball is drawn from the following sources: Robert Weintraub, The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Little Brown & Co., 2013); John Klima, The Game Must Go On: Hank Greenberg, Pete Gray, and the Great Days of Baseball on the Home Front in WWII (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015); William B. Mead, Baseball Goes to War (Washington: Farragut Publishing Co., 1985); Steven Bullock, Playing for Their Nation: Baseball and the American Military During World War II (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004); David Finoli, For the Good of the Country: World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002); “OISE Base Takes GI World Series: 50,000 See All-Stars Defeat Third Army by 3-2 in Ninth Inning of Deciding Game,” New York Times, September 9, 1945; Tim Wendel, “The G.I. World Series,” December 10, 2015, thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/gi-world-series; Robert Weintraub, “Three Reichs, You’re Out: The Amazing Story of the U.S. Military’s Integrated ‘World Series’ in Hitler Youth Stadium in 1945,” Slate, April 2013, slate.com/articles/sports/sports_nut/2013/04/baseball_in_world_war_ii_the_amazing_story_of_the_u_s_military_s_integrated.html.

69 Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 91. See also Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, 61-62.

70 Quoted in Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1964).

71 Bullock, Playing for Their Nation, 60-61.

72 “Nahem Sets Sunset League Pace,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1943; “Les Horn Wins Batting Crown,” Newport (Rhode Island) Mercury, September 17, 1943.

73 “Big War Bond Show Is Set for Tonight,” New York Times, June 17, 1944; “Sports Carnival Attracts 30,000; Varied Program Staged at the Polo Grounds,” New York Times, June 18, 1944.

74 “Nahem Stages One-Man Show,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1944.

75 Captain Robert H. Wormhoudt from Iowa helped Nahem organize the OISE All-Stars, although it is unclear what his role was; he did not play on the team. The Des Moines Register reported that “It was he [Wormhoudt] who organized the OISE base nine, which won the G.I. world series from the Third Army’s 71st Division team, 3 games to 2, last fall.” See Sec Taylor, “Sittin’ In With the Athletes,” Des Moines Register, January 27, 1946. Wormhoudt’s sons John and Dan knew nothing about their father’s involvement with baseball during the war. But in a phone interview Dan explained that his father grew up in and around Des Moines, dropped out of the University of Chicago, and in the early 1930s moved back to Iowa, where he worked as a union organizer in a steel mill in Davenport. According to Dan Wormhoudt, his father was a member of, or close to, the Communist Party and remained a radical for the rest of his life. He also loved literature and later became a published poet. Nahem pitched for the Dodgers’ minor league team in Clinton, Iowa, during the 1937 season, so it is possible that these two radicals met in Iowa and then joined forces when they were both stationed in Rheims, France, eight years later to pull together the OISE team. It is more likely, however, that they met for the first time in France. Both were stationed in Rheims as part of the antiaircraft artillery division. They shared political views and literary tastes, so it wouldn’t be surprising that they met each other and became friends. After the war, Wormhoudt moved to New York City to work in broadcasting, but was blacklisted during the McCarthy era and moved to California, where he eventually became manager of public relations for Disneyland. Phone conversations with John Wormhoudt (June 11, 2018) and Dan Wormhoudt (June 22, 2018); email from Dan Wormhoudt (June 23, 2018).

76 Nahem and Bauers had pitched against each other in 1935 when Nahem played for Allentown and Bauers played for Hazleton in the New York-Pennsylvania league. See “Miracles? — Just Two Hazleton Victories As Wilson Pitches, Dormat Hits Home Run,” Hazleton (PA) Plain Speaker, August 27, 1935.

77 “70th Anniversary of the 1945 ETO World Series,” Baseball in Wartime, Issue 39, September/October 2015 baseballinwartime.com/BIWNewsletterVol7No39Sep-Oct2015.pdf.

78 sabr.org/bioproj/person/49784799.

79 sabr.org/bioproj/person/f6e24f41.

80 “70th Anniversary of the 1945 ETO World Series.” An Associated Press story in the Des Moines Register a few months later claimed that the OISE team was 37-3 that season. See Sec Taylor, “Sittin’ In With the Athletes,” Des Moines Register, January 27, 1946.

81 “70th Anniversary of the 1945 ETO World Series.”

82 “3d Army, Oise Nines Gain ETO GI Finals,” New York Times, September 1, 1945.

83 Blackwell was one of the strongest opponents of baseball integration and Jackie Robinson. Rampersad, Jackie Robinson, 183; Roger Kahn, Rickey and Robinson: The True Untold Story of the Integration of Baseball (New York: Rodale, 2014), 255.

84 The stadium’s playing surface was so big that it fit a baseball diamond, a soccer field, and a football field at the same time. German POWs had been ordered to build extra bleachers to accommodate the large crowd. Putting a baseball field in Hitler’s stadium was a powerful symbol. “We had a conqueror’s frame of mind,” recalled one American soldier. “The Germans had surrendered unconditionally, and this proved it.” See Weintraub, The Victory Season. See also Raymond Daniell, “Nazi Shrine in Nuremburg Stadium Now Serves as a Ball Field for GI’s,” New York Times, June 28, 1945.

85 “3d Army Nine Slaps Com Z, 9-2, in Opener,” London Stars and Stripes, September 4, 1945; “3rd Army Cops Series Opener at Nuremburg,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1945.

86 “Com Z Evens Series With 2-1 Decision,” London Stars and Stripes, September 5, 1945.

87 “Oise Nine Beats Third Army,” New York Times, September 6, 1945.

88 Ibid.

89 Contemporary accounts of the final game agree that Keane took over for Nahem in the fourth inning and pitched the rest of the game, and that Richardson knocked in Smayda for the winning run. See “OISE Base Takes GI World Series: 50,000 See All-Stars Defeat Third Army by 3-2 in Ninth Inning of Deciding Game,” New York Times, September 9, 1945; “All Stars Win European Title in GI Playoff,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1945; and “OISE Nine Captures ETO Baseball Crown,” London Stars and Stripes, September 10, 1945. The account on the Baseball in Wartime website agrees with these accounts. The accounts in Weintraub’s The Victory Season (page 61) and in SABR’s profile of Russ Bauers (sabr.org/bioproj/person/4c6acb7c) report that Bauers came in to relieve Nahem. But Bauers relieved Day in the fourth game for 5⅔ innings, making it unlikely that he would have pitched in the next game. baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/bauers_russ.htm. The Victory Season also has a different account of the OISE win. Weintraub writes that Nahem put Leon Day in the game as a pinch-runner in the seventh inning and that Day quickly stole second, then stole third base, and then raced home on a shallow fly ball, tying the score. Weintraub also reports that Willard Brown knocked in the winning run in the eighth inning. I’ve found no other accounts of the final game that corroborate this version of events. In an email to me on December 28, 2017, Weintraub generously acknowledged that his account of that game is probably mistaken.

90 “All Stars Win European Title in GI Playoff,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1945.

91 Weintraub, The Victory Season.

92 There’s no record of how Walker, an Alabaman, felt about playing on a team with two black players or about competing against an all-black team. He and his brother Fred “Dixie” Walker, a Dodgers outfielder, were unhappy when the Dodgers brought Jackie Robinson to the big leagues. Accounts vary about whether the grumbling by the Walker brothers and other players (particularly those, like Harry, who played for the Cardinals) evolved into a plan by some players to go on strike rather than play against Robinson. If such a plan was ever hatched, it quickly fizzled, but both Walker brothers were branded as racists and were both soon traded. Years later, Harry Walker was asked about the incident but avoided a direct answer. “Nothing was ever concrete on it,” he said. “There was a rumor spread through the whole thing. And everybody was involved to a point, but that was never done.” George Vecsey, Stan Musial: An American Life (New York: ESPN, 2011), cited in sabr.org/bioproj/person/3bbe3106#sdendnote14sym. The players’ rebellion against Robinson is described in Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman, Rampersad, Jackie Robinson; Kahn, Rickey & Robinson, and Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment. Kahn claims that Dixie Walker explained the secret plan to him in detail. Corbett disputes the existence of a players strike against Robinson in Warren Corbett, “The ‘Strike’ Against Jackie Robinson: Truth or Myth?”, Baseball Research Journal (SABR), Spring 2017. sabr.org/research/strike-against-jackie-robinson-truth-or-myth.

93 “Leon Day,” Baseball in Wartime, baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/day_leon.htm.