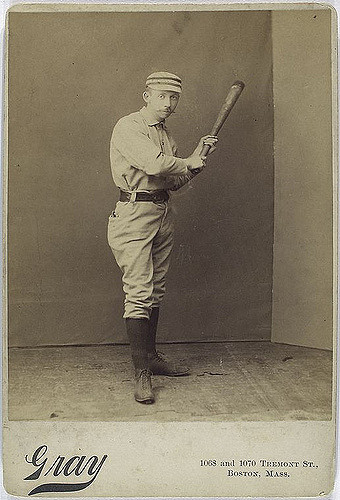

Arthur Irwin

Even for serious fans of early baseball, it can be difficult to know what to make of Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame member Arthur “Foxy” Irwin. On one hand, Irwin popularized the baseball glove, inspired a character in a Zane Grey novel, and served as a team captain, player-manager, manager, scout and minor-league owner during a career that lasted more than 40 years. On the other hand, few early baseball figures were as polarizing.

Even for serious fans of early baseball, it can be difficult to know what to make of Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame member Arthur “Foxy” Irwin. On one hand, Irwin popularized the baseball glove, inspired a character in a Zane Grey novel, and served as a team captain, player-manager, manager, scout and minor-league owner during a career that lasted more than 40 years. On the other hand, few early baseball figures were as polarizing.

In The National Game (1910), Al Spink wrote that there was “no speedier or brainier fielder and batsman” in the 1880s and he said that Irwin was the best scout employed by the New York Highlanders.1 Referencing Irwin’s time as a manager, writer Roy Kerr described him as “a skinny, bug-eyed Canadian with large, protruding ears and a healthy ego. He was an impeccable dresser, and fancied himself to be a savant in the art of ‘scientific baseball.’”2 Daniel Levitt has characterized Irwin as “one of the slimier men in baseball,”3 and pitcher Waite Hoyt said that he was “probably the most disgusting man [he] ever knew.”4

Curiously, however, after it was reported in July 1921 that Irwin jumped off a passenger steamer to his death in the Atlantic Ocean, the discussion was not about differing opinions of Irwin’s character. Instead, people argued over the basic facts. One man said that Irwin was still alive, others suspected murder, and two complete strangers each claimed to be his wife.

Arthur Albert Irwin was born in Toronto on Saint Valentine’s Day of 1858. His father, who was born in Ireland in 1833 and who was also named Arthur, worked as a blacksmith. His mother, Elizabeth, was a homemaker; census records inconsistently describe her as a native of Ireland or Canada. By 1870, the younger Arthur had six siblings, all but one being younger than him.

The Irwin family moved to Boston when Arthur was six. He grew up playing sandlot baseball in South Boston, where his friends included future major-leaguer Tommy McCarthy.5 Beginning in 1873 with the Aetna Club of Boston, Irwin spent several seasons as a shortstop in amateur baseball.6

On June 2, 1879, Irwin made his professional debut with the Worcester Worcesters of the minor-league National Association in an exhibition against the Chicago White Stockings. Worcester pitcher Lee Richmond also debuted that day, throwing a no-hitter in a rain-shortened seven-inning game. Irwin played third base for that first game before he moved to shortstop, and he made two stellar plays that day.7

Boosted by a 47-win season from Richmond, who also hit .369, the Worcester club played well enough to move into the National League for the 1880 season. This meant that Irwin and the other players received major-league promotions without changing teams. A highlight that year came on June 12, when Richmond pitched the first major-league perfect game and Irwin scored the game’s only run.8 In 85 games, Irwin registered a league-leading 345 assists.

Irwin missed much of the 1881 season owing to an early-season illness and a broken leg later in the year. The leg injury occurred while Irwin was running the bases, and local sports equipment salesman Martin “Flip” Flaherty was inserted into the game in his only major-league appearance.9

The Worcester club folded after an 18-66 season in 1882. Irwin moved on to the NL’s Providence Grays as a team captain. Gloves were only worn by catchers and first basemen at that time, but Irwin needed to play with two broken fingers one day in 1883. He fashioned a padded buckskin driving glove into a mitt and wore the glove even after his fingers healed. Monte Ward also started wearing the glove, and it was standard throughout the league by 1884. Sporting goods company Draper & Maynard produced a model based on “the Irwin glove” and they said that 90% of major leaguers wore its brand by the 1920s.10

The 1884 Grays won the precursor to the modern World Series – a best-of-three series against the AA champion New York Metropolitans. In 1885, the Grays folded after a fourth-place finish and Irwin was looking for a team again. He had not displayed his characteristic speed and defensive range since the 1881 leg injury. The introduction of overhand pitching in 1884 provided another challenge; already light-hitting, Irwin batted under .240 after that point in his career.11

In 1886, Irwin signed with Philadelphia of the NL. For the next three years, Irwin played at least 100 games per year. He posted mediocre offensive numbers in Philadelphia, but he led NL shortstops in 1888 with a career-high 204 putouts.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on May 27, 1889, that the Phillies had been benching Irwin.12 He briefly returned to the field after an injury to Ed Delahanty, but his relationship with the team was irreparable after the initial benching. He was sold to the Washington Senators for $3,000 on June 8 and became a team captain.13 Within a month of Irwin’s arrival in Washington, he was named player-manager. It was Irwin’s first major-league managerial opportunity and he was the team’s fifth manager in only three years.14 His predecessor had started the season with a 13-38 record and Irwin fared marginally better, finishing 28-45 as manager for the last-place team.

By this time, many players resented their controlling NL owners, and Irwin was becoming known as a key man in the players union called the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players. He helped to organize the Players’ League and he purchased 12 shares of stock in the league’s Boston club.15 Irwin appeared in 96 games for the 1890 Boston Reds. The team won the PL championship, but that league folded, and the Boston Reds joined the AA with Irwin as manager for 1891.

More than a year removed from playing in the NL, Irwin got on the bad sides of NL owners. In an era of competition among baseball leagues, a document known as the National Agreement of 1883 restricted how major-league and minor-league teams could pursue players from other leagues. Before the 1891 season, AA teams began disregarding the agreement in the pursuit of NL players. NL executives believed that Irwin had encouraged AA teams to break the agreement.16

If that wasn’t enough to spark resentment, NL owners also felt that Irwin had convinced Cincinnati Reds owner Al Johnson to move his team from the NL to the AA. Though Johnson sold the team before the 1891 season started and the club returned to the NL without having played in the AA, Irwin’s reputation was damaged in baseball’s most powerful league.17

Irwin also struggled for the approval of Reds players. In the middle of 1891, when Reds infielder Hardy Richardson was injured and Paul Radford would not play on Sundays, Irwin signed his younger brother, John Irwin, despite John’s known fielding struggles. Teammates and local writers cried nepotism, but John struggled through 19 games over several weeks before the elder Irwin relented and dropped him from the team.18 Irwin could focus on managing, as he played in only six games, and the 1891 Boston Reds won the AA.

That fall, Irwin made headlines after alleging game fixing in the NL pennant race. Irwin said that Cap Anson of the Chicago Colts had agreed to play Irwin’s Reds in an AA-NL championship series if the teams won their leagues, but he said that the Giants had agreed to throw a late-season series to the Boston Beaneaters so that Boston could beat Chicago to the pennant. Irwin accused Buck Ewing of giving away the Giants’ signs. No one on either team commented on Irwin’s allegations.19 Once the Beaneaters and Reds won their leagues, Beaneaters manager Frank Selee refused to play a postseason series against the Reds.20

In 1892, Irwin returned to Washington to manage the Senators when Billy Barnie had a disagreement with team owners after the second game of the season. The NL was using a split-season format to determine who would make the league championship. Washington was 35-41 in the first half, earning seventh place, but fans disliked Irwin. When the team started poorly in the second half, he was fired.21

Irwin began managing the Philadelphia Phillies in 1894. He had not played in the major leagues since 1891; he played in one game for the 1894 Phillies, his last major league playing appearance. He had big shoes to fill as a manager; baseball pioneer Harry Wright had just managed there for ten seasons. Wright had been successful with other teams, but his contract was not renewed in Philadelphia because he had not secured any first-place finishes.22 The team had led the league in hitting for in 1893 and again under Irwin in 1894 and 1895. The 1895 team brought in 474,971 fans, a 19th century single-season record.23

Despite that apparent success, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported in September 1895 that Irwin was thinking about leaving. The Inquirer called Irwin “the clearest sighted and coolest headed manager in the business to-day.”24 In early October, Irwin said he would not return to Philadelphia. He was trying to purchase the Toronto club in the Eastern League.25

Irwin had a 149-110 record with the Phillies, but he had irked their personnel and their fans. He meddled in the team’s uniform decisions, resulting in unpopular red and black bars being placed on their leggings. Owner John Rogers criticized his lax handling of players, but even the players disliked Irwin, especially in comparison to his predecessor. On the field, Irwin introduced intricate strategy, but these tactics often confused his players.26

Irwin had also served as the University of Pennsylvania baseball coach from 1893 to 1895.27 There Irwin coached future author Zane Grey. Grey’s first baseball book, The Short-Stop (1914), is dedicated in part to Irwin; his second baseball book, The Young Pitcher, included a character known as Worry Arthurs, a fictionalized version of Irwin.28 29

In the mid-1890s, Irwin became very active outside of baseball. He invented a miniature football scoreboard to reproduce games in faraway cities and he started the short-lived American League of Professional Football, the country’s first professional soccer league. He promoted boxing matches and organized roller hockey games and marathon bike races.30

Soon after leaving the Phillies, Irwin became manager of the New York Giants for 1896, working out a clause with owner Andrew Freedman to ensure that Irwin had complete control of the team.31 Early on, Irwin showed aptitude for identifying talent, but he may have had less authority than promised. He had scouted future star Nap Lajoie in the minor leagues, and he attempted to convince Freedman to pay $1,000 for Lajoie and another player, but Freedman refused.32

Irwin created a farm team in Jersey City and he did have enough authority to name his brother John the manager of those prospects.33 Irwin created a book of hand signs for his players to study on their own time.34 He was fired after a 36-53 start, a record that looks worse when compared to the team’s 28-14 finish under his successor, Bill Joyce.35

In 1897, Irwin became part-owner of the Toronto club in the Eastern League. During an 1898 dispute with the league’s players over the length of the season and the players’ compensation, Irwin was criticized by The Buffalo Enquirer for assuming “a know-it-all air which oftentimes gives his friends a very severe pain in the neck.”36

In 1898, Irwin raised some suspicions by trading away several Toronto players to the Washington Senators before being announced as Washington’s manager the next year.37 Irwin and Toronto’s co-owners hired future major-league executive Ed Barrow to manage that team for the 1900 season.38 After leaving Washington in 1900, Irwin never coached or managed in the major leagues again. He retained partial ownership in Toronto for at least a few more years.39

When the American League was being organized in January 1901, Ban Johnson and Connie Mack sought an AL site in Boston. Irwin owned a potential site known as Charles River Park. Mack visited Irwin’s home to discuss the use of the park. Irwin, who was sick with the flu, hesitated to lease the park to the AL.40 At the time, the AA was trying to revive itself as a major league and Irwin tentatively controlled the Boston AA team. Irwin said he might lease the park in exchange for a stake in the Boston AL club, but he hesitated to commit to anything. Mack tired of Irwin’s indecisiveness and approached Hugh Duffy, who suggested land off Huntington Avenue that could house a baseball park. The AL signed a lease at the Huntington Avenue Grounds on January 16.41 The NL and the Players’ Protective Association reached an agreement a month later that refused to recognize the AA as a major league.42

In 1902, Irwin returned as the Penn baseball coach and then had a short stint in the NL as an umpire.43 From 1903 to 1907, he was a minor-league manager for teams in Toronto, Rochester, Kansas City, and Altoona. He signed on as manager for the Washington club in the short-lived Union Professional League in 1908.44 Reports as early as that year refer to Irwin as a New York Highlanders scout.45 He was described as the team’s “chief scout” by 1909.46 He attempted to use binoculars to steal signs from New York’s opponents that year, but it did not take long for the opposition to stop the behavior by bringing it to the attention of the league.47

As a scout, Irwin was persistent. For example, in 1910, he heard about young minor-league pitcher Ray Caldwell in Pennsylvania. Arriving the day after Caldwell had pitched, Irwin stayed until Caldwell’s next appearance. Caldwell was knocked out of that game early, but Irwin liked Caldwell’s mechanics and followed the team for a few more days. Caldwell then threw a 14-inning shutout and Irwin signed him that day. The pitcher won 134 major-league games in 12 seasons, though his potential was somewhat stymied by a drinking problem.48

A 1912 Harper’s Weekly piece called Irwin “the dean of scouts.”49 After that season, the Highlanders made Irwin business manager.50 The next year, columnist Sam Crane wrote that Irwin was a good judge of talent, hampered only by managers who mishandled that talent.51 Highlanders manager Frank Chance disagreed; he resigned in 1914 after two seasons and said Irwin had failed to find him any quality players. President Johnson seemed to side with Irwin, calling the manager “the biggest individual failure in the history of the American League… Chance failed to develop even one man of class.”52

Irwin certainly thought outside the box in New York, establishing a spring training site on a cricket field in Bermuda in 1913.53 Irwin resigned when the team was sold after the 1914 season. He became part-owner and manager of the minor-league Lewiston Eagles in 1915.54 Three years later, he began a three-year stint managing the International League’s Rochester Hustlers. In 1921, he managed the Hartford Senators of the Eastern League. He caused Lou Gehrig to lose a year of collegiate eligibility after convincing the Columbia University star to play some games with Hartford.55

Irwin had gained a lot of weight after his playing days, but in 1921 he had digestive problems and dropped 60 pounds in two weeks. The illness forced him to stop coaching and he was hospitalized with stomach cancer that June. The next month, he boarded a steamer from New York to Boston. He told other passengers that he was going home to Boston to die, but he never made it there, and he is thought to have jumped overboard on July 16.56

Things had gotten complicated when Irwin’s son Harold visited him in the hospital and learned of an unknown brother, Herbert, who had also visited. It turned out that Irwin had married Elizabeth in Boston in 1883, and they had Herbert and two other children. While coaching at Penn in the 1890s, Irwin met May. They moved to New York, lived as husband and wife, and had a son named Harold.57

It would be an exaggeration to say that Irwin lived an intricate double life. Rather than rushing between two families in separate cities, Irwin spent almost all his free time and money on May and Harold, visiting Boston so infrequently that no one in New York suspected another relationship. When he visited Boston, he often misspoke, referring to Herbert as Harold. Elizabeth’s family had long suspected that Irwin had another woman. Shortly before his death, Irwin sent Elizabeth $500 in revenues from his scoreboard enterprise, enclosing a note saying, “God bless you all.” Irwin indicated that he could not send more money because his bills had been very costly, but the destitute Elizabeth had been surprised even by the money he did send. Finances aside, Elizabeth said she was happy to know that Irwin had been en route to Boston to be with her in the end.58

Elizabeth was accepting of suicide as her husband’s cause of death, but the circumstances still inspired conspiracy theories. Some people wondered the possibility of murder, and one player said that he saw Irwin in Oklahoma after he was said to have died.59

Irwin was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1989.

Author’s note

In addition to the sources listed below, the author consulted Irwin’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame and U.S. census records from the 1850s to the 1870s, and he utilized statistics from Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Alfred Henry Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Company, 1910), 228.

2 Roy Kerr, Sliding Billy Hamilton: The Life and Times of Baseball’s First Great Leadoff Hitter (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010), 93-94.

3 Daniel Levitt, Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 37-38.

4 Levitt, 37-38.

5 Donald Hubbard, The Heavenly Twins of Boston Baseball: A Dual Biography of Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 35.

6 George Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club: A Concise and Accurate History of Base Ball from its Inception (Boston: M.F. Quinn & Co., 1897), 211-212.

7 John Husman, “Lee Richmond’s No-Hit Debut”, in Bill Felber, Mark Fimoff, Len Levin, & Peter Mancuso (eds.), Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games that Shaped the 19th Century (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013), 114.

8 David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 162.

9 Mike Passey, “Martin Flaherty,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/df77d4e0, accessed December 16, 2017.

10 Josh Leventhal, History of Baseball in 100 Objects (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2015), 84.

11 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 465.

12 “A Captain Will Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 27, 1889, 6.

13 “Captain Arthur Irwin Released,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 10, 1889, 6.

14 Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 71.

15 Robert Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016).

16 “Base Ball Comment,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 15, 1891, 3.

17 “Base Ball Comment.”

18 Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, 411.

19 Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, 465.

20 Marty Appel., Slide, Kelly, Slide: The Wild Life and Times of Mike King Kelly (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1999), 164.

21 Brett Abrams, Capital Sporting Grounds: A History of Stadium and Ballpark Construction in Washington, Part 3 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 35.

22 Christopher Devine, Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Base Ball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 162.

23 Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, 697.

24 “Manager Arthur Irwin Contemplates Retiring from the Philadelphia Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1895, 5.

25 “Sporting Chat,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 8, 1895, 5.

26 Roy Kerr, Sliding Billy Hamilton: The Life and Times of Baseball’s First Great Leadoff Hitter, 93-94.

27 “Penn Baseball in the 19th Century: From Student Origins to University Administration,” Penn University Archives & Records Center, http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/sports/baseball/1800s/hist3.html.

28 Zane Grey, The Short-Stop (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1914).

29 Samuel Hughes, Penn In Ink: Pathfinders, Swashbucklers, Scribblers & Sages: Portraits from The Pennsylvania Gazette (Xlibris, 2006), 57.

30 Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, 697.

31 “A Running Review of Sporting News,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 28, 1895, 5.

32 Ronald T. Waldo, Characters from the Diamond: Wild Events, Crazy Antics, and Unique Tales from Early Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 47.

33 “Giants to Play Mets,” The Journal, April 10, 1896, 12.

34 Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006), 75.

35 Ronald Mayer, Christy Mathewson: A Game-by-Game Profile of a Legendary Pitcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 12-13.

36 “Manager Irwin Accuses President Franklin of Squaring Proper Authorities,” Buffalo Enquirer, May 16, 1898, 6.

37 Kevin Plummer, “Historicist: Playing the Field,” https://torontoist.com/2014/03/historicist-playing-the-field/, accessed December 16, 2017.

38 Daniel Levitt, Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty, 37.

39 Plummer, “Historicist: Playing the Field.”

40 Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball, 188-190.

41 Macht, 188-190.

42 “Baseball Rules Changed,” New York Times, February 28, 1901.

43 Ronald Waldo, Characters from the Diamond: Wild Events, Crazy Antics, and Unique Tales from Early Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 64.

44 “Union League’s Local Officers,” Washington Evening Star, March 6, 1908, 15.

45 “New First Baseman for New Yorks,” New York Sun, October 2, 1908, 8.

46 “World Series Doomed?” Courier-Journal, January 3, 1909, 30.

47 “Sign Stealing an Ancient Art in Majors,” St. Petersburg Times, July 19, 1959, 3C.

48 Charles Faber and Richard Faber, Spitballers: The Last Legal Hurlers of the Wet One (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006), 98-100.

49 Edward Lyell Fox, “The Baseball Scout,” Harper’s Weekly, July 27, 1912, 11.

50 “Arthur Irwin is Business Manager of Highlanders,” Hartford Courant, December 6, 1912, 18.

51 Sam Crane, “Yankees Scout is Valuable Asset,” El Paso Herald, November 18, 1913, 7.

52 Ed Bang, “Frank Chance Without Peer as a Failure,” Pittsburgh Press, November 28, 1914, 14.

53 “Yankees Will Have Hotel to Themselves,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 10, 1913, 9.

54 “Irwin in Lewiston,” Fitchburg Sentinel, February 18, 1915, 2.

55 James Lincoln Ray, “Lou Gehrig,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ccdffd4c, accessed December 16, 2017.

56 “Irwin’s Double Life Bared by Suicide,” New York Times, July 21, 1921.

57 “Hid Double Life for 27 Years,” Gettysburg Times, July 22, 1921.

58 “Irwin’s Double Life Bared by Suicide,” New York Times, July 21, 1921.

59 Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball, 697.

Full Name

Arthur Albert Irwin

Born

February 14, 1858 at Toronto, ON (CAN)

Died

July 16, 1921 at ---, Atlantic Ocean (At Sea)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.