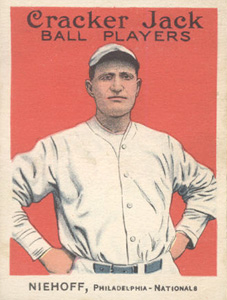

Bert Niehoff

Although no more than that of a journeyman, the six-year major-league playing career of Bert Niehoff was not without its highlights. In 1915 he combined with future Hall of Fame shortstop Dave Bancroft to form the middle infield of the pennant-winning Philadelphia Phillies. The following year, Niehoff led the National League in doubles and was second in extra-base hits. While he was with the New York Giants two seasons later, a pop-fly collision with outfielder Ross Youngs brought the big-league tenure of Bert Niehoff to an abrupt end. His right leg broken just below the knee, the 34-year-old infielder would never play another major-league game. But while his major-league days were over by June 1918, Niehoff’s association with professional baseball had almost another 50 years to run. First as a minor-league player and then as a longtime manager, he remained in uniform into the 1950s. Thereafter, Bert began scouting for major-league clubs, finally retiring from the game in 1967 at the age of 83.

Although no more than that of a journeyman, the six-year major-league playing career of Bert Niehoff was not without its highlights. In 1915 he combined with future Hall of Fame shortstop Dave Bancroft to form the middle infield of the pennant-winning Philadelphia Phillies. The following year, Niehoff led the National League in doubles and was second in extra-base hits. While he was with the New York Giants two seasons later, a pop-fly collision with outfielder Ross Youngs brought the big-league tenure of Bert Niehoff to an abrupt end. His right leg broken just below the knee, the 34-year-old infielder would never play another major-league game. But while his major-league days were over by June 1918, Niehoff’s association with professional baseball had almost another 50 years to run. First as a minor-league player and then as a longtime manager, he remained in uniform into the 1950s. Thereafter, Bert began scouting for major-league clubs, finally retiring from the game in 1967 at the age of 83.

Baseball lifer John Albert “Bert” Niehoff was born in Louisville, Colorado, on May 13, 1884, one of six children born to German immigrant mining engineer Carl B. Niehoff (born 1840) and his Missouri-born wife, Emilie (born 1847).i Bert attended local schools and completed his freshman year at Louisville High School before starting his working life as a clerk in the grocery store of brother-in law William Austin.ii In September 1905 Bert took a local girl named Mabel Rule as his bride, commencing a marriage that would last 66 years. By 1907 the young couple had relocated to Denver, where Bert found work as an electrician and where the birth of son Lloyd made the Niehoff family complete.

The Boulder County area where Bert grew up was rugged territory known for two things: coal mines and summer baseball leagues.iii As a youngster, Niehoff had honed his diamond skills playing on local sandlots and Louisville’s showcase Miners Field. Midway in 1907, 23-year-old Bert Niehoff belatedly entered the professional ranks. He signed with the Pueblo Indians of the Class A Western League, but was cut after a brief tryout as a right-handed pitcher.iv Bert then returned to his electrician job in Denver. Undiscouraged, he hooked on the following spring as an infielder with another Western League club, the Des Moines Boosters. Installed as the team’s regular third baseman, the 5-foot-10, 175-pound righty-batting Niehoff hit only a meager .215 for the last place (54-94) Boosters. The 1909 season, however, would feature a sharp upturn in the fortunes of both Bert Niehoff and the Des Moines club. Largely behind the yeoman mound work of big leaguers-in-waiting Frank Lange (29-12) and Frank Miller (24-16), the Boosters surged to the top of the Western League standings, snatching the pennant in a .003 photo finish over rival Sioux City. Bert Niehoff contributed his share to the club’s dramatic triumph. He batted a respectable .269 and was sound defensively in the field, his play prompting the Chicago White Sox to purchase his contract at season’s end. But in the first of several career false starts, Niehoff failed to impress during the White Sox spring camp and was optioned back to Des Moines in March 1910. Back with the Boosters, Bert upped his offensive numbers, batting .293, with 51 extra-base hits, for a roster-depleted club that fell to seventh place in the Western League.

Niehoff’s performance earned him another big-league shot in 1911. That season commenced with two events that would recur with regularity during Niehoff’s baseball career. First, he would always prove a tough negotiator when it came to contract terms. Although he had not yet played a major-league game, Bert unilaterally revised the terms of the pact sent to him by his new club before returning it to the Pittsburgh front office. Fortunately for Niehoff, Pirates president Barney Dreyfuss admired the gall of this unproven newcomer and ratified the contract as revised by Niehoff.v The second characteristic displayed by Bert that spring was far more detrimental to his prospects than hard-nosed contract negotiating: a chronic inability to hit well in the early going. As during the previous year, Niehoff failed to impress with the bat during spring training and was sent back to the minors, sold to the Indianapolis Indians of the Double-A American Association in April 1911. Under the impression that the almost 27-year-old Niehoff was still a youngster – for years major-league records listed 1889, rather than the actual 1884, as the year of his birth – a rapid recall by Pittsburgh was predicted by the sporting press.vi Instead, Niehoff’s fortunes continued to plummet. Unable to hit at Indianapolis – he batted .143 in 23 games for the Indians – Niehoff was demoted to the Omaha Rourkes of the Western League, the Class A minor league where he had begun his professional career five summers earlier. There, Bert regained his bearings. He hit .269 for the remainder of the 1911 season and then turned it up the following year, batting .291, with 57 extra-base hits, for Omaha in 1912.

Again benefiting from the impression that he was a young ballplayer, Niehoff had his contract purchased by the Louisville Colonels of the American Association for the 1913 season. This time he proved his mettle against Double-A pitching, upping his batting average to .296, with 51 extra-base hits. At the close of the American Association campaign, Neihoff was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds, then in firm possession of seventh place in the National League standings. Reaching the club in time to see some late-season action, Bert made his major-league debut on October 4, 1913, going 0-for-4 against St. Louis right-hander Pol Perritt. The following day, he took the collar again in the 1913 season-ender, leaving him with a .000 batting average for his initial two-game major-league stint. Still, the season had been a success for Bert Niehoff, with local sportswriters penciling him in for third base on the 1914 Reds.vii But over the winter the Cincinnati faithful were disturbed by reports that the upstart Federal League was making a concerted effort to sign Niehoff, a situation that he used to his advantage when negotiating with Reds management. Ultimately, Bert remained loyal to his new club but proved unable to avoid his habitual slow hitting start that spring. He was also plagued by a charley horse and other minor injuries in the early going. With the Reds in rebuilding mode, manager Buck Herzog stuck with his “young” third baseman, and his patience was rewarded. By midseason, Niehoff was performing solidly with both bat and glove and had cemented his place in the everyday Cincinnati lineup. A performance tailspin in late July was attributed to the distraction of renewed courtship of Niehoff by the Federal League, and Bert thereafter regained form.viii He finished the season with decent, if unspectacular, stats for the last place (60-94) Cincinnati Reds of 1914: .242/4/49 with 20 stolen bases, while playing a slightly better than average third base (35 errors in 461 chances for a .924 fielding percentage).ix Despite the faith that he had shown in Niehoff earlier, manager Herzog, a volatile, aggressive personality, did not get along with his taciturn third sacker. In the offseason, Herzog remedied the situation by getting rid of Niehoff, sending him and cash to Philadelphia in exchange for veteran catcher Red Dooin. Once with the Phillies, the major-league career of Bert Niehoff would reach its modest summit.

For the 1915 campaign, Philadelphia manager Pat Moran converted Niehoff into a second baseman. Far from graceful – particularly compared with shortstop Dave Bancroft – Bert struggled with the transition, leading National League second sackers in errors committed (50). But he also exhibited good infield range, placing second in assists by a second baseman (411) during the season. At the plate, Niehoff (.238/2/49, with 21 steals) was a complementary member of a lineup that relied on sluggers Fred Luderus and Gavvy Cravath. But the key to the Phillies’ success was a pitching staff anchored by Grover Cleveland Alexander, the league leader in wins (31), strikeouts (241), ERA (1.22), and various other hurling categories in a grueling 376 innings pitched. Under the capable direction of manager Moran, Philadelphia (90-62) cruised to the 1915 National League flag, seven games better than the defending champion Boston Braves. But the joy of winning a pennant would soon yield to despair in the World Series, particularly for Bert Niehoff.

Going into the postseason, the Phillies were rated a clear underdog to the Boston Red Sox, the American League standard-bearer. One of the positions where Boston was given a decided edge was second base, where syndicated sports columnist and noted World Series prognosticator Hugh Fullerton summed up the situation thusly: “Perhaps no comparison between players on the rival teams … shows more superiority one over the other than does [Red Sox] Jack Barry over Niehoff. It is the wily, foxy veteran, hardened in hundreds of battles, brainy and a born leader, against an ordinary ballplayer without great experience, who is hustling, doing just the best he can, and improving.”x Although the slick-fielding Barry was not much of a hitter (.220 BA in 1915), Fullerton figured him to be “much better than that in the series,” particularly compared with Niehoff, who the scribe predicted would not bat .150 against the Red Sox staff of Smoky Joe Wood, Babe Ruth, Ernie Shore, and Dutch Leonard.xi A week later Niehoff made Fullerton a prophet. He batted a dismal .063 (1-for-16), with five strikeouts, as Boston took the World Series handily in five games.

Bert Niehoff rebounded from his woeful Series performance by having the best season of his major-league career in 1916. Although his batting average was no better than a mediocre .243, he led the National League in doubles (42) and placed second in extra-base hits (50). He also posted personal bests in hits (133), runs scored (65), RBIs (61), slugging percentage (.356), and OPS (.648). In the field, however, Niehoff remained erratic, charged with another 50 errors but again showing good range, finishing second in assists by a NL second baseman (437). He also turned more double plays than any other National League player at his position. The Phillies as a whole, meanwhile, near duplicated their log of the previous season. But in 1916 a 91-62 mark was good only for second place, 2½ games behind the pennant-winning Brooklyn Robins.

With the demise of the Federal League drastically reducing player negotiating leverage, Philadelphia stood firm in the annual contract battle with Niehoff. The 1917 season had already commenced by the time he accepted the $4,000 offer tendered by the club. Even without the benefit of spring training, Neihoff got off to an uncharacteristically good start with the bat, but the club grew dissatisfied with his unreliable work in the field. In mid-July, the Phillies acquired accomplished second baseman Johnny Evers from Boston, reducing Niehoff to a backup role at third base and first base. In significantly reduced at-bats, Bert hit a personal best .255, but with only 17 doubles and 23 total extra-base hits. With the World War threatening the 1918 major-league playing schedule, the Phillies jettisoned the now expendable Neihoff, trading him to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Mule Watson just as the season was about to commence. But the now 34-year old infielder proved a bust with the Cardinals, and was waived after batting a paltry .179 in 22 early-season games. He received a final major-league chance when the New York Giants signed him to fill in at second base while regular Larry Doyle recuperated from surgery. Seven games into his Giants tenure, the major-league playing career of Bert Niehoff came to a sudden conclusion when “his right leg was broken just below the knee in a collision with Ross Young[s] in the first inning.”xii In time, the injury healed but by then Bert had been released by New York. His major-league playing career was finished.

In six big-league seasons, Niehoff posted a career .240 batting average, with 135 of his 489 hits going for extra bases. Despite some high error totals, he had been a slightly better than average infielder, with a lifetime .940 fielding percentage.xiii Although his time in the big show had been relatively short, Niehoff had put it to good use, carefully observing the performance of his betters and developing into a keen student of the game. A long future in the professional ranks stood before the quiet, sober Niehoff, as various baseball organizations would seek his services for the next 50 years. In the short run, however, Bert wanted to continue his playing career. Unable to gain a contract for the 1919 season from the Giants, he spent the year in the Double-A Pacific Coast League, first playing for the Seattle Rainiers, then the Salt Lake City Bees, before finally settling in as the regular third baseman for the Los Angeles Angels. For the following two campaigns, Niehoff was an infield regular for the Angels, his .293 batting average in 179 games helping Los Angeles to the 1921 PCL crown.

In 1922 Bert took a step down on the competitive level, but a big step up in responsibility, signing on as player-manager of the Mobile Bears of the Class A Southern Association. That season proved a singular success. As the club’s regular second baseman, he fielded well and at the plate he hit .295, with ten home runs. More important, the Niehoff-led Bears posted a sparkling 97-55 record and captured the pennant. The season’s triumph was then made complete by Mobile’s defeat of the Fort Worth Panthers of the Texas League in the 1922 Dixie Series, the annual postseason clash between the championship nines of the two Class A circuits. In 1923 the Bears slipped to second place but manager Niehoff nonetheless achieved a personal goal: a .303 batting average, the only time in 21 seasons of playing in Organized Ball that he would enter the charmed batting circle. For the 1924 season, Bert transferred to the Atlanta Crackers, a Southern Association rival that he would lead for the next five years. The 1925 season was a pennant-winning year for the Crackers, who lost the Dixie Series to Fort Worth. Thereafter Atlanta tumbled into the Southern Association’s second division. Late in the 1928 campaign and with the club headed for a seventh-place finish, manager Niehoff was released by Atlanta. The severance also terminated the playing career of the Atlanta skipper, a now 44-year-old veteran who had taken the field in 50 games that season. Not counting the Pueblo tryout of 1907 (for which no records survive), Bert Niehoff’s 2,140 career base hits yielded him a lifetime .272 batting average in 16 seasons of combined Double-A/Class A game action. And at that point his managerial log stood at 585-486 (.546), with two Southern Association pennants to his credit.

For the 1929 and 1930 seasons, Bert and longtime Chicago White Sox catcher Ray Schalk served as coaches for New York Giants manager John McGraw. The next three seasons saw Niehoff back in a Southern Association dugout, this time serving as manager of the Chattanooga Lookouts. His tenure as field leader got off on a storied note. Two batters into the first inning of an April 2, 1931, exhibition game against the fearsome New York Yankees, Niehoff pulled his starter and brought in a replacement to face Babe Ruth: Virne Beatrice “Jackie” Mitchell, a 17-year-old lefty and Organized Baseball’s first female pitcher.xiv The consummate ham, Ruth swung mightily but missed Mitchell’s first two offerings and then loudly demanded that umpire Brick Owens inspect the baseball. The Bambino then took a called third strike and trudged glumly back to the bench, much to the delight of the hometown crowd. Sans the theatrics, next batter Lou Gehrig then went down swinging. After slugger Tony Lazzeri had tried to bunt, Mitchell was lifted and the Yanks went back to work in earnest, demolishing the Lookouts, 14-4. Several days later, Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis voided the Mitchell contract on the ground that professional baseball was “too strenuous” for women.xv The remainder of the Chattanooga season was less eventful, the Lookouts finishing fourth (79-74) in the final standings. The following year, the Lookouts went 98-51 during the regular season, won the Southern Association playoffs, and then captured the Dixie Series, beating the Texas League Beaumont Explorers in five games.

After Chattanooga finished fifth in 1933, Bert Niehoff briefly left Organized Baseball, spending 1934 tending to his offseason insurance business in Denver. Back in managerial harness with the Oklahoma City Indians of the Texas League in 1935, Bert guided his new club to the league pennant and a Dixie Series triumph over Atlanta, his third win in the prestigious postseason match. After a second year at the Oklahoma City helm, Niehoff moved up to the Double-A ranks, taking the reins of the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. Bereft of talent, the Colonels finished in the cellar during both 1937 and 1938. At the close of the latter season, the sale of the club to Tom Yawkey, owner of the Boston Red Sox, and Donie Bush left Bert without a job and free to accept the Giants’ offer to manage its Jersey City affiliate in the Double-A International League. The 1939 regular season was a great success, with the Little Giants (89-64) winning the pennant and drawing home crowds double that of its International League competitors.xvi Unhappily for Bert, that good fortune did not continue in the league playoffs, Jersey City being knocked out in the opening round by the Newark Bears, the top farm team of the hated Yankees. The following season, the Bears swept Jersey City in four postseason games. Days later, New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham sacked Niehoff.

Returning to the Southern Association, Bert managed the Little Rock Travelers (1941) and the Knoxville Smokies (1942) to second-division finishes. The following two years saw Niehoff among the former big leaguers engaged by the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, managing the South Bend Blue Sox club of Bonnie Baker/Doris Barr/Dottie Schroeder fame. He returned to the helm of the Chattanooga Lookouts for the 1945-1947 campaigns but proved unable to replicate earlier successes, his club losing in the first round of the Southern Association playoffs all three years. He then spent two years scouting for the New York Yankees. Thereafter, Niehoff returned to uniform to manage the Selma Cloverleafs of the Class B Southeastern League (1951) and the Saginaw Jacks of the Class A Central League (1952).xvii At the age of 70, he was still at it, guiding the Oak Ridge Pioneers of the Mountain States League until that Class C circuit disbanded in July 1954, bringing, at long last, the minor-league managing career of Bert Niehoff to a close. In 24 different seasons between 1922 and 1954, Niehoff-led teams had gone a combined 1,824-1,713 (.516) while winning four pennants and three Dixie Series. Bert’s two seasons managing in the AAGPBL added another 115 wins (and 95 losses) to his overall professional log.

In retirement, Bert and wife Mabel resided in Inglewood, California. But that retirement would not be permanent. In February 1961 general manager Fred Haney announced that the American League expansion Los Angeles Angels had retained 77-year-old Bert Niehoff as their talent scout for the greater San Fernando Valley area. Niehoff continued in that post until he finally retired for good in 1967. Still, he stayed active, mostly on the local golf courses. A first-rate shot-maker even as an old man, Bert recorded a well-publicized hole-in-one in May 1974, just after his 90th birthday.xviii Later that year he contracted cancer and died quietly at home in Inglewood on December 9, 1974. Following funeral services, John Albert Niehoff was laid to rest beside Mabel (who had died in 1971) at Inglewood Park Cemetery. The only immediate survivor was his unmarried son, C. Lloyd Niehoff. Endowed with only limited playing ability but infused with a passion for baseball, Bert Niehoff devoted virtually his entire 60-year working life to the game, being one of that legion of unsung men who helped sustain the sport through the better part of the 20th century.

Notes

i Sources for the biographical details of this profile include the Bert Niehoff file at the Giamatti Research Center, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data, and various of the newspaper items cited below. Unless otherwise noted, the statistical information in this biography has been taken from www.Baseball-Reference.com.

ii Hall of Fame questionnaire completed by Bert Niehoff in 1960 and US Census data. Grocery store owner Austin was married to Bert’s older sister Josephine, and the Neihoff and Austin families lived under the same roof in Louisville.

iii The combustible properties of the region’s low grade sub-bituminous coal made the mining and transportation of ore prohibitively hazardous in hot weather. Idled mine workers filled the summer work void by organizing a host of local baseball leagues.

iv The statistical record for Niehoff’s brief time with the Pueblo club is lost.

v Sporting Life, February 25, 1911.

vi Although in photographs Niehoff looked a good deal older, Pirates owner Dreyfuss maintained that “in real life, ‘Bertie’ is not over 21 years old, just right for fast company in a few months” when he was likely to be recalled by the Pirates, according to sportswriter A.R. Cratty in Sporting Life, April 22, 1911.

vii Niehoff would be joining a Reds team already suffused with Teutonic surnames – Herzog, Hoblitzel, Groh, Von Kolnitz, Koestner, Schneider, Uhler, Berghammer, etc. – prompting one waggish observer to later remark that announcement of the Cincinnati lineup sounded like “roll call at the Reichstag.” See New York Times, June 14, 1914.

viii The unsettling effect of Federal League blandishments was believed to be the cause of a midseason slump that briefly led to Niehoff’s benching, as per Cincinnati sportswriter Ren Mulford, Jr. in Sporting Life, August 22, 1914. At the season’s end, New York sportswriter Bill MacBeth maintained that Neihoff and the Federal League Chicago Whales had actually come to terms, but that Whales manager Joe Tinker had rescinded the pact after seeing Niehoff make a number of “bungling mistakes” playing against the Cubs. Sporting Life, October 3, 1914.

ix One respected baseball encyclopedia estimates Niehoff’s fielding at seven runs saved over the norm for 1914 third basemen. See Total Baseball, 7th ed., John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, eds. (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 1052.

x As published in the New York Times, September 29, 1915, and elsewhere.

xi Ibid.

xii “Cy Williams [of the Phillies] lifted a short fly to right which was pursued by Niehoff and Young, the latter seeing that a collision was imminent, hurled himself to the ground in an effort to avoid the second baseman. Unfortunately, Niehoff stumbled over the youngster as he lay prone on the ground, and as he fell in a heap his right leg snapped under him.” New York Times, June 1, 1918.

xiii For his major-league career, Neihoff received a rating of 18 runs saved as a fielder from Total Baseball.

xiv The first notable female baseball player may have been Dr. Alta Weiss, who pitched for the semipro Vermillion (Ohio) Independents in 1907 and thereafter financed her medical-school education as a barnstormer. The signing of women players was not formally outlawed by Organized Baseball until 1952.

xv For a fuller account of the game and its aftermath, see Michael Aubrecht, “Jackie Mitchell: The Pride of the Yankees,” at www.baseball-almanac.com/articles/aubrecht8.shtml.

xvi On April 20, 1939, the Jersey City Giants drew 45,112 fans for a game against the Buffalo Bisons. The 378,325 home attendance figure posted by Jersey City for the entire season exceeded its nearest International League competitor by more than 150,000, and was greater than the home attendance of five major-league teams in 1939. See Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997), 306.

xvii The Wikipedia entry for Bert Niehoff has him as general manager of the Mobile Bears in 1952.

xviii According to news reports, Bert holed out a four-iron on the 145-yard third hole of the Roosevelt Course in Griffith Park. See, e.g., Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1974. Two years earlier he had caused a stir with 200-plus-yard drives at a baseball old-timers outing.

Full Name

John Albert Niehoff

Born

May 13, 1884 at Louisville, CO (USA)

Died

December 8, 1974 at Inglewood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.