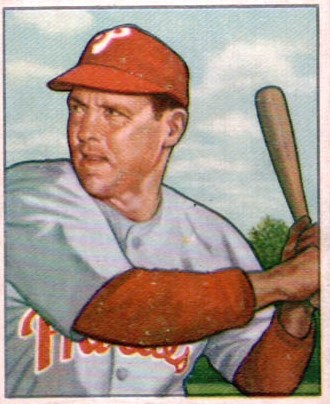

Bill Nicholson

llReal Cubs fans never called him Swish. To them he was Big Bill, or Nick. The Swish nickname originated in Brooklyn. The big left-handed hitter always leveled his bat across the plate several times when stepping in to face an opposing pitcher. Dodgers fans would yell, “Swish, swish, swish,” in unison with his practice swings. The name caught on on the East Coast, but was soundly rejected in Chicago. Because news is written in New York, the Swish designation survived and Big Bill has been all but forgotten.

llReal Cubs fans never called him Swish. To them he was Big Bill, or Nick. The Swish nickname originated in Brooklyn. The big left-handed hitter always leveled his bat across the plate several times when stepping in to face an opposing pitcher. Dodgers fans would yell, “Swish, swish, swish,” in unison with his practice swings. The name caught on on the East Coast, but was soundly rejected in Chicago. Because news is written in New York, the Swish designation survived and Big Bill has been all but forgotten.

Nicholson was the prototypical home-run hitter of the early 1940s. His numbers don’t look impressive today, but in that low-octane era, 20 homers was a big deal. He led the Cubs in home runs eight seasons in a row, a mark that was tied by Ernie Banks and broken by Sammy Sosa. From 1940 through 1944, Nicholson never finished lower than fourth in the National League in home runs. Although he topped 30 only once, he led the league in homers and RBIs in back-to-back seasons, 1943 and 1944. Only Babe Ruth and Jimmie Foxx had done that previously. Granted, those were war years, but Nicholson had solid seasons both before and after World War II depleted major-league rosters.

Nicholson was the most popular Cub of the decade of the ’40s, the idol of urchins everywhere who identified with the North Siders. A husky 205-pound 6-footer, he was usually seen on the field with a big chaw of tobacco bulging in his cheek. When the Cubs were losing, people didn’t start leaving the park until his last at-bat. That successful formula of one big slugger and a beautiful ballpark wasn’t lost on Phil Wrigley. In subsequent years of futility, although high-profile boppers like Hank Sauer and Ernie Banks were surrounded by inferior supporting casts, the turnstiles kept clicking as long as they were hitting.

William Beck Nicholson was born on December 11, 1914, on the family farm just outside Chestertown, Maryland, located across Chesapeake Bay from Baltimore. He was a three-sport athlete at Chestertown High School, graduating in 1931 at age 16, and enrolled at Washington College in his hometown. Founded in 1782, this small liberal-arts institution is the 10th oldest college in the country. George Washington donated money to its founding, served on its board, and granted the use of his name.

Nicholson was the eighth and (as of 2014) last Washington College baseball player to make it to the majors. He had the longest and most successful career among them. (The first was Al Burris, whose career was limited to one game in 1894.) Big Bill starred as a guard on the basketball team and as a fullback and kicker on the football team. His goal at the time was to be a naval officer, so in 1933 he left for the Severn School in Annapolis to prepare for entrance to the Naval Academy. He was rejected due to colorblindness, a serious blow at the time, but this was the factor that led to his draft deferment during World War II, and his career years in baseball.

Returning to Washington College in 1934, Bill led the football team to its first and only undefeated season. (The college dropped football as a varsity sport in 1950.) He played center field on the baseball team, leading the 1935 and ’36 teams to the Maryland Intercollegiate Baseball League championships, hitting .571 in ’36. At the time of his graduation, Nicholson was regarded as one of the greatest athletes in the college’s history, and is a member of its Hall of Fame.

Ira Thomas, a catcher on the great Philadelphia Athletics teams of the early teens, scouted Nicholson for the A’s and signed him. Connie Mack‘s A’s at the time were doormats of the American League, having sold off their stars like Lefty Grove and Jimmie Foxx because of the Depression. Nicholson got a $1,000 signing bonus and a salary of $1,200 for the rest of the 1936 season. A week too late, the Yankees offered $5,000.

Desperate for warm bodies, the A’s brought Nicholson up to the big club, but he had only a dozen at-bats, struck out five times, and didn’t get a hit. He was invited to spring training with the A’s in 1937, but was sent to Class B Williamsport before opening day. Despite hitting .300 with 20 homers in each of two minor-league seasons, he was traded to the Washington Senators with $30,000 for outfielder Dee Miles in August 1938. Things turned around when Nicholson’s manager at Chattanooga, former Cubs star Kiki Cuyler, tinkered with his stance and batting style. He had Bill crouch more and stop lunging at outside pitches. Cuyler not only is credited for transforming the failed prospect into a feared power hitter, but also recommended him to the Cubs scouting staff.

Nicholson became a Cub in midseason 1939, just after the end of a dynasty when the Cubs won four pennants in 10 years (but lost every World Series). That dominant team was breaking up as a result of old age (Gabby Hartnett, Charlie Root) and bad trades (Billy Herman, Augie Galan, Dolph Camilli). But the deal for Nicholson was a good one. For $35,000 they bought the .334-hitting right fielder from the Chattanooga Lookouts. He hit a home run in his first game as a Cub, had three hits including a triple in his second game, and never looked back.

Nicholson quickly settled in as the Cubs’ regular right fielder and cleanup hitter. A National League All-Star in 1940 and 1941, he hit 25 and 26 homers, and drove in 98 runs both years. In the field, he gained a reputation for his strong throwing arm, and throughout his career was one of the toughest hitters to double up, hitting into DPs only once in every 91 at-bats.

Teammate Don Johnson recalled, “Nick was one of the neatest guys you ever wanted to meet … built like a fullback, a quiet guy. … He was a real good outfielder, covered more territory than you thought. … I don’t think I ever saw him throw to a wrong base.”1

The next few years provided plenty of highlights. The first back-to-back-to-back homers in Cubs history were hit by Phil Cavarretta, Stan Hack, and Nicholson on August 11, 1941, off Lon Warneke. But it wasn’t enough, as the Cubs lost to the Cardinals, 7-5.

On August 15, 1942, Nicholson hit three home runs, two doubles, and a single in a doubleheader against the Pirates. Again it was to no avail as the Cubs were swept. They did better a week later when catcher Clyde McCullough, shortstop Lennie Merullo, and Cavarretta turned a triple play against the Reds in the top of the 11th. Big Bill sent the fans home happy with a walk-off homer in the bottom of the inning off Gene Thompson.

Nicholson’s career years came during the war, in 1943 and 1944. That certainly had to affect his standing among all-time Cubs. And despite his efforts, both were losing seasons for the North Siders. The numbers only begin to tell the story. In ’43 he hit .309 and led the league with 29 homers and 128 RBIs. The following year he hit .287, leading the league with 33 homers, 122 RBIs and 116 runs scored. He lost out by one point in the MVP voting to Cardinals shortstop Marty Marion, a .267 hitter who didn’t lead the league in anything but fielding percentage. But the Cardinals won their third straight pennant, while the Cubs languished in fourth place.

Big Bill provided Cubs fans with some unforgettable moments during those dismal years. The Cubs went 32 games in 1943 before hitting their first home run. (Part of the blame was assigned to the infamous balata ball, used early that season due to rubber shortages.) Nicholson ended the drought with two homers on May 30. Two months later, on July 30, Phil Cavarretta hit a home run off Wrigley Field‘s foul pole against the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Johnny Allen. The ball was retrieved (due to wartime shortages), put back in play, and Nicholson hit it out of the park. It was probably the only time that two consecutive home runs were hit with the same ball.

Nicholson’s greatest day in baseball occurred on July 23, 1944, in a doubleheader against the Giants. New York manager Mel Ott paid him the ultimate tribute by ordering him intentionally walked with the bases loaded in the eighth inning of the second game. Until then, only Napoleon Lajoie and Del Bissonette had received intentional passes with the bases loaded. (Barry Bonds joined the club in 1998 and Josh Hamilton in 2008.) Nicholson had hit three home runs in the opener, one in the nightcap, and one in his last at-bat the day before. That set records with four consecutive home runs, and four in a doubleheader. Ott’s strategy backfired, because the Cubs scored three runs in the eighth to tie the game. But New York scored twice in the bottom of the inning to finally win, 12-10. An interesting sidelight was that Ott and Nicholson were tied at the time for the league lead with 21 home runs each.

After five solid years of stardom, the bottom suddenly dropped out for Nicholson just as the Cubs got it together for their surprise pennant in 1945. His batting average dropped to .243, with only 13 homers and 88 RBIs. He hit only .214 in the World Series, but drove in eight runs in the seven games. That tied a record at the time. Things got even worse in 1946, an injury-plagued season, as he hit just .220 with 8 homers and 41 RBIs. Despite the anemic power numbers, he still tied Cavarretta for the team lead in home runs. Nobody has ever satisfactorily explained the reason for that two-year slump. Nicholson was diagnosed with diabetes in 1950 while playing for the Phillies, but it’s doubtful that he was suffering from its effects that early.

In 1947 Nicholson made a comeback of sorts, hitting 26 homers with 75 RBIs, and leading the league’s outfielders in fielding average. He also led the league in strikeouts with 83, barely a half-season’s output for today’s free swingers. In 1941 Nicholson struck out 91 times, the only time he was over 90, yet was in the top three in the league six times. That’s another reason why the name Swish stuck.

There were still some highlights left in his big bat. On August 8, 1947, Cubs lefty Johnny Schmitz was locked in a classic pitchers’ duel with the Reds’ stringbean side-armer Ewell Blackwell. The score was 1-1 in the bottom of the 11th when Nicholson launched one of Blackwell’s fastballs into the right-field bleachers.

A year later he hit one of the longest home runs in the history of Wrigley Field, a towering blast just to the right of the scoreboard that hit a building across Sheffield Avenue. Several years later, Roberto Clemente hit one to the left of the board.

At age 33 in 1948, Bill had his final season as a regular, and his last with the Cubs. As soon as the season ended, he was traded to the Phillies for former batting champion Harry Walker. After a couple of months in 1949, Walker was shipped on to the Reds for Hank Sauer, who continued the Nicholson power-hitting tradition, albeit in left field instead of right. With the Phillies, Nicholson played in only 98 games, hitting .234 with 11 home runs. Something was obviously wrong.

Even so, Nicholson was a steadying influence on the young Whiz Kids, who would stun the baseball world with a pennant in 1950. Throughout that season, though, he lost 20 pounds, and on Labor Day was diagnosed with diabetes. He missed the rest of the season including the World Series. Nicholson came back to play three more years with the Phillies, primarily as a pinch-hitter. He retired at age 38, after 16 seasons in the major leagues. In that time, he hit .268 with 235 home runs and 948 RBIs. He was a National League All-Star four times.

During his career with the Cubs, Nicholson hit 205 home runs, which as of 2014 ranked eighth on their all-time list. Eight of them were grand slams, second only to Ernie Banks. Nicholson was named to the Cubs’ All-Century Team. In an interview during the 1980s, he said, “Just give me grass, daylight ball, and another pennant flying over Wrigley Field.”2

Although he had a reputation as a great clubhouse influence, Nicholson was not offered any managerial or coaching jobs after retirement. He tried his hand at real estate and running a bowling alley, and for a while was a race-track inspector. But he was happiest working on his 120-acre farm. A life-size statue of Bill, swinging a bat, was erected in Chestertown’s main square, next to the town hall on Cross Street, in 1992. Weakened by the effects of diabetes, he died of a heart attack on March 8, 1996, at the age of 81, and is buried outside Old St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in his hometown. Bill was the last survivor of his immediate family. Two wives and two children died before him.

Sources

Gold, Eddie, and Art Ahrens, The New Era Cubs (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985).

Golenbock, Peter, Wrigleyville (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996).

Chicago Cubs 1948 Yearbook.

Greenberg, Robert A., “When Billy Nick Met Connie Mack,” Washington College Magazine, Spring 2006 (magazine.washcoll.edu/2006/spring/03.php)

Greenberg, Robert A., “Swish” Nicholson, A Biography of Wartime Baseball’s Leading Slugger (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008).

baseball-reference.com/n/nichobi01.shtml

thedeadballera.com/GravePhotos/Nicholson.Bill.Grave.html

baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/N/Nicholson_B…

baseballhalloffame.org/exhibits/online_exhibits/baseball_enli…

Notes

1 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 285.

2 Eddie Gold and Art Ahrens, The New Era Cubs (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985), 15.

Full Name

William Beck Nicholson

Born

December 11, 1914 at Chestertown, MD (USA)

Died

March 8, 1996 at Chestertown, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.