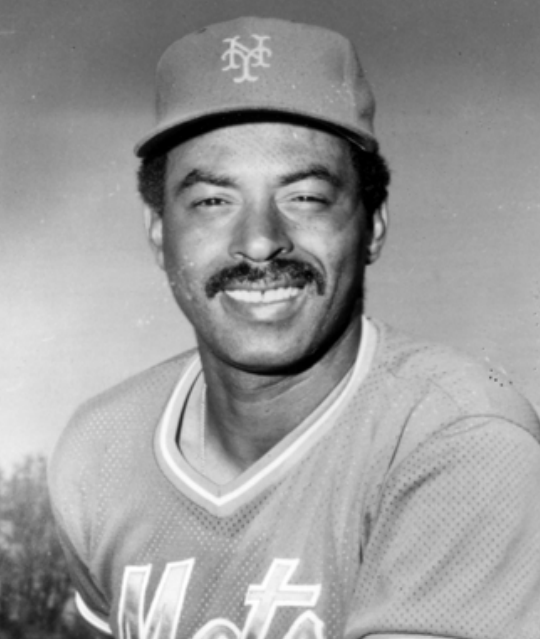

Bill Robinson

It was one week into the 1977 season. Jim Kaplan of Sports Illustrated alluded to 34-year-old Bill Robinson’s frustrations in his 10th major-league season:

“No matter where he is playing — be it Cincinnati or New York or Los Angeles — he is sure to hear it. ‘Weaser,’ someone will call to him from the stands. ‘Hey, Weaser.’ And Bill Robinson of the Pirates will know someone from his hometown of Elizabeth, Pa., just outside Pittsburgh, is on hand. Why was he given the name? Robinson doesn’t know. What does Weaser mean? That’s also a mystery. The nickname is downright befuddling, which makes it especially appropriate for Robinson, a .300 hitter with power and a good glove who, confoundingly enough, cannot get a regular job. ‘I am the No. 1 utility man in baseball,’ he says joylessly.”1

“But in the Panglossian (excessively optimistic) world of Pittsburgh’s new manager, Chuck Tanner, Robinson occupies the best of all possible positions. “ ‘People call him a super-sub,’ says Tanner. ‘I call him a super-regular. He’s more valuable than most regulars, because he can play so many positions.”2

“Robinson’s pre-batting ritual includes a quick Lord’s Prayer while he crosses himself several times. Then he rubs his forehead from eyebrows to hairline with the middle and index fingers of his right hand, a relaxation technique he picked up from a kinesiologist. Finally Robinson assumes an upright stance made all the more menacing by his 6′ 3″, 200-pound frame3 and lashes downward at the ball with a whippy 33-ounce bat. ‘I try to make the top of the ball mine,’ he says. ‘I swing for grounders and line drives. After all, how often does a guy drop a fly? But the big thing is, I’ve learned to relax and meet the ball instead of trying to overpower it. I’ve eliminated the word “pressure” from my vocabulary.’”4

“ ‘His attitude has changed completely,’ says Del Unser of the Expos, a close friend and former teammate of Robinson’s in Philadelphia. ‘He was very high-strung with the Yankees [1967-69] and at times with the Phillies [1972-74]. Now he can wait out a pitcher and hit breaking stuff. I think if he hadn’t had to break in as a Yankee, he’d have been where he is now five years ago.’”5

William Henry Robinson Jr., the first-base coach and hitting instructor for the 1986 New York Mets, was born on June 26, 1943, in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. His father, Bill Sr., was a steelworker. His mother, Millie Mae, was a cook in a restaurant, and when the scouts visited during Bill’s senior year of high school, she made sure they were well fed.

Robinson starred in baseball (as a pitcher/outfielder) and basketball at Elizabeth-Forward High School in McKeesport and had a basketball scholarship offer from Bradley University. He chose baseball and was signed in June 1961, when he graduated from high school, by John O’Neil of the Braves for a figure between $12,000 and $16,000.

Robinson’s career got off to a less than resounding start. His travels began in 1961 at Wellsville in the Class D New York-Penn League. Although he batted only .239, he had 15 doubles in 67 games and was off to Dublin in the Georgia-Florida League for the 1962 season. While there, he experienced the racial segregation that was inherent in the South in those years, but did not let it affect his play on the field. From there, Robinson headed up the ladder. He batted .304 at Dublin and followed that up with a .316 at Waycross in the Class A Georgia-Florida League the following season. At Waycross he had 10 home runs, a league-leading 132 hits and 10 triples, 62 RBIs, and 29 stolen bases. He topped the league with a .478 slugging percentage. The 1964 season found him at Yakima in the Class A Northwest League, where he had his best season so far, banging 24 doubles and 18 homers with 81 RBIs en route to a .348 batting average in 104 games.

Robinson had married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Alice Moore, in December 1963. Bill III came along in 1964 and Kelly was born in 1969. The Robinsons eventually settled in Washington Township, New Jersey. Bill was active in his community and received the George Washington Carver Award for community service in 1978.6

Despite his achievements, Robinson gained the reputation as a worrier, as noted in a small piece in The Sporting News in 1965.7 Robinson spent all of the 1965 season with the Atlanta Crackers, the Braves’ Triple-A farm team. He got off to a great start with three hits in his first game and went 7-for-16 in his first four games. The accolades were flowing and Toledo’s manager, Frank Verdi, considered him to be “the best looking rookie I have seen in the league this year.”8 For the season, he batted .268. In 1966 the Milwaukee Braves moved to Atlanta, and the Braves moved their Triple-A team to Richmond. Robinson responded to the move with a .312 batting average and career highs of 20 home runs and 79 RBIs. He was named to the International League All-Star team.

Robinson, then 23, was called up to the Braves at the end of the 1966 season and saw his first action on September 20. He ran for Henry Aaron and finished the game in right field. His first hit came on September 25. Starting the game in left field, he singled in the eighth inning off Pittsburgh’s Al McBean, driving in a run. He was given another start in the season finale against Cincinnati and went 2-for-4, including his first major-league extra-base hit, an RBI triple. In his six games with the Braves, he went 3-for-11.

But the Braves were fully stocked with outfielders and traded Robinson to the New York Yankees for Clete Boyer. The aging Yankees had fallen on hard times, falling to sixth in 1965 and 10th in 1966. Roger Maris had been traded to St. Louis, and it was expected that Robinson would take over in right field.

Robinson was counted on to save the franchise, and things started off fairly well. As Robinson remembered it, “(W)e opened in Washington (on April 10), and I hit a home run my first time up in an 8-1 win. They said ‘God’s here.’”9 The score was actually 8-0, with the win going to Mel Stottlemyre, who limited the Senators to two hits.

As Marty Appel notes in Pinstripe Empire, “Robinson was a personal favorite of (team president Mike) Burke’s. He wanted him to succeed badly. He was tall and rangy, he was black, and he seemed like a good statement for a team ‘moving in new directions.’”10 Burke was alluding to the fact that since Jackie Robinson entered baseball in 1947, the Yankees had been very slow to integrate, with only one black player of note, Elston Howard, playing for the club during the first 20 years of integration.

But the rest of the 1967 season for Bill Robinson was a disappointment. He suffered a shoulder injury, which he tried to hide. The fans were tough on him. “The boos really tore me up when I was with the Yankees,” he said in 1974. “All ballplayers hear them and I couldn’t take it. I’d be across the George Washington Bridge and heading home (to New Jersey) before the people even got to the clubhouse. I just couldn’t face it anymore.”11 He batted only .196 with seven homers and 29 RBIs in 116 games, as the Yankees placed ninth for their third consecutive lower division finish.

Looking back on his season, Robinson said, “I was pressing too hard. Every time I came up, I wanted to hit a home run to impress people. Finally it got to the point where I was holding the bat so tightly I couldn’t even hit the ball.”12

Postseason shoulder surgery repaired the injury, but Robinson continued to struggle. He batted .240 in 1968 and .171 in 1969. In 1970 he was sent down to Triple-A Syracuse and batted .258. In December the Yankees traded Robinson to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher Barry Moore.

Appel noted, “It would forever be a mystery as to what went wrong with Bill Robinson in New York, and why that promise was never fulfilled”13 (until he shined for Philadelphia and Pittsburgh).

The White Sox sent Robinson to Triple-A Tucson (Pacific Coast League), where he batted .275 with 14 homers and 81 RBIs in 1971. Frustration set in when he was not called up to the White Sox, and he even thought about quitting. His hopes were renewed when Chicago dealt him to the Philadelphia Phillies for minor-league catcher Jerry Rodriguez.

In 1972 Robinson was still in the PCL, this time with Eugene, and batted .304 with 20 homers and 66 RBIs in 66 games. That earned him a call-up to Philadelphia in June, and he saw his first action with the Phillies on June 24, doubling against the Expos in a pinch-hitting role. During his days in the minor leagues, he learned of what he came to call the Willie Davis theory, which goes as follows: “It’s not my life, and it’s not my wife, so why worry about it.” Basically, he learned not to dwell over everything and only worry about items of the utmost personal importance. The theory stood him well as he embarked on the most productive years of his career. There would be bumps along the way, but, for the most part, Robinson took things in stride and learned to relax.

Robinson got into 82 games with the Phillies in 1972, batting .239, but was in the majors to stay.14 Actually, when he came to spring training in 1973, he was still 52 days short of qualifying for the major-league pension plan. Job number one was just to make the team. He exceeded all expectations. New manager Danny Ozark inserted Bill into the lineup more regularly and he batted .288 with 25 home runs and 65 RBIs in 124 games. It appeared as though Robinson had it made. Manager Ozark remarked, “He gave it his all and produced. I understood the problems he had in New York. He wasn’t sure of himself. Now he’d got the confidence. If he could go back 10 years, he would be another Aaron or Mays.”15

No sooner was Robinson a regular than his bad luck returned. He had offseason surgery for bone chips in his left elbow and found that, despite his fine performance, he came to spring training in 1974 without a regular job. A somewhat overblown dispute with Ozark would ultimately result in his leaving the Phillies.

“I saw the lineup card without my name on it and took a swipe at it, not meaning to touch it,” Robinson recalled. “But it came off, and Ozark was watching. He called me into his office, which he had a perfect right to do, and we both let off a lot of steam. When I was leaving, I tried to close the door gently, but there was a breeze and it slammed.”16

Robinson got into only 100 games with Philadelphia in 1974 and his average dropped to .236 with only 5 home runs and 21 RBIs. After the season, he was traded to Pittsburgh for pitcher Wayne Simpson, and with the Pirates he blossomed.

Robinson joined the Pirates in 1975 at the none-too-tender age of 32 and was the fourth outfielder behind Richie Zisk, Al Oliver, and Dave Parker. He batted .280 with 6 homers and 33 RBIs. He started 41 games for the Pirates and had 16 multiple-hit games. The Pirates won the National League East title before being swept by Cincinnati in the League Championship Series. Robinson went hitless in two at-bats in the LCS.

The following season, Robinson saw more action, with 416 at-bats in 121 games. His batting average soared to .303, his first time above 300. He was the Pirates’ leading right-handed slugger and the team’s most valuable player. He received the Roberto Clemente Memorial Award from the Pittsburgh sportswriters. He performed at five different positions and pinch-hit .455.17 His power numbers were solid (21 homers, 64 RBIs) and the best was yet to come.

Off this showing, Robinson was slated for third base in 1977, but once again he would be denied. The Pirates traded for Phil Garner. Instead of blowing up as he had in Philadelphia, he calmly talked out his disappointment with two friends from his minor-league days and his father. “They all told me the same things,” Robinson said, “that I still had a job and that things could be worse. So I didn’t do anything rash, and I’m glad. We got a heck of a third baseman in the deal, and because I had thought I would start, I had gotten into the best shape of my life mentally and physically.”18

“It’s true we led Bill to believe he’d be starting at third this season,” said General Manager Pete Peterson, “but we couldn’t resist picking up Phil Garner from the A’s. He (Garner) plays third, and Willie Stargell plays first. We want to stick with Al Oliver in left and Dave Parker in right, and we feel Omar Moreno in center gives us the kind of outfield defense we haven’t had since Roberto Clemente. Not that Bill isn’t good defensively. He is, and he’s our top sub at all five positions. He may not get 400 at bats, but he’ll get plenty with his versatility.”19

It wasn’t long before Robinson saw action, filling in for injured Pirates in the outfield and at first base. It was early on that the Pirate injury list started to grow, and Robinson was a disgruntled bench warmer for just the first four innings of the season. When Al Oliver was sidelined because the pain from a mouth ulcer became too acute, Robinson moved into the outfield. Two games later, Stargell began suffering, first from a strained right knee, then from dizzy spells, and Robinson was moved to first base. Through the first seven games of the season, he was hitting .348 and leading the Bucs with eight runs batted in. There was even talk in Pittsburgh that the Pirates would trade one of their regulars so that Robinson can have a spot to call his own in the lineup.20

Despite this early activity, he was hampered by muscle pulls in his legs and started only 19 games during the first two months of the season. Everyone seemed to have suggestions to get him going and, at the suggestion of teammate Rich Gossage, he took to wearing pantyhose beneath his uniform pants.21 He took more than his share of kidding, but went onto start 32 consecutive games between May 31 and July 2, batting .339 over that stretch.

It got better. From July 21 through August 2, Robinson had a power surge. He had five homers, including grand slams on July 28 and July 30, and batted in 21 runs. His batting average during the 13 games was .390 and his slugging percentage was a hefty .712. But he did not forget that it had not always been so easy. He could relate to “the guys sitting on the bench, because I have been in their spot for a long, long time. The toughest part of coming off the bench is that you know eventually you’re going back to the bench. That’s tough for any athlete to take.”22

On August 15 of that season, the Pirates issued a press release which highlighted his exploits from June 24 through August 2, a period during which he had eight game winning hits. It was also noted that through August 14, he had come to the plate 24 times with a runner on third with less than two out, and driven in the runner on 22 of those occasions.23

For the record, Bill Robinson in 1977, despite not being a “regular”, played in 137 games, 127 as a starter. The versatile Robinson started 79 games at first base, 11 games at third base, 36 games in left field, and 1 game in center field. He came to the plate 544 times. He set career highs, batting .304 with 26 homers and 104 RBIs.

During the offseason, Al Oliver was traded and Bill Robinson, at age 35, became the everyday left fielder in 1978. However, his numbers dropped off significantly. He batted only .246 with 14 home runs and 80 RBIs. A thumb injury early in the season set him back and as he continued to fail to produce, he began to press. Manager Chuck Tanner and his teammates were in his corner. Tanner said, “You don’t give up on his type. He’s giving it all he has and one day he’ll get it all back and he’ll win plenty of games for us.”24

Robinson didn’t let his off year at the plate affect his fielding as he led National League left fielders with a .989 fielding percentage. He stole a career high 14 bases. He did have his moments during the season, with a pair of two-home-run games against the Cubs at Wrigley Field.

And then came 1979. Robinson got his home-run swing back and slammed 24 along with 75 RBIs as the “We Are Family” Pirates won their division for the sixth time in 10 years, and the first time since 1975. Robinson appeared in a career record 148 games for Pittsburgh, again without a regular position or place in the lineup. He was platooned with John Milner, and when Willie Stargell needed a rest, the Pirates would play both Robinson and Milner, and they were up to the task.

Actually, the Pirates got off to a slow start in 1979. They were six games under .500 on May 16 before taking 16 of 21 games to move into third place, three games out of first. During that stretch, Robinson batted .322 with seven homers and 19 RBIs, including two homers in a win on June 6. As the Pirates righted their ship, Robinson said “It was just a case of putting it together. We know we have the talent here. We know we can win. We have all the ingredients of a winner and many of us are tired of finishing in second place.”25 But then, the team treaded water.

As late as July 8, they were in fourth place, seven games behind the league leaders. Then they took off. They won 16 of 21 to move into first place for the first time on July 28. It became a two-team race between the Pirates and the surprising Montreal Expos the rest of the season.

On the decisive last day of the campaign, the Pirates hosted the Chicago Cubs. Robinson came off the bench in the top of the sixth inning to replace Milner in left field. His first, and only, plate appearance was in the bottom of the seventh inning. He came to the plate with the bases loaded and two outs. He delivered a single, driving in two runs to give the Bucs a 5-2 lead. The final score was 5-3, and the victorious Pirates advanced to the postseason. They defeated the Reds in the NLCS to advance to the World Series against Baltimore. After going 0-for-3 in the LCS, Robinson went 5-for-19 in the World Series as the Pirates defeated the Orioles in seven games. Robinson had his first World Series ring, and a full World Series share worth $28,236.87.

During the offseason, the Pirates, looking to shore up their pitching, offered Robinson as trade bait, but there were no nibbles.26 Injuries plagued Robinson in 1980, and he played in only 100 games, 74 as a starter. He batted .287 with 12 home runs and 36 RBIs. The following season, he saw even less action, batting .216 and playing in only 39 games. The Pirates finished third in 1980 with an 83-79 record and, in the strike-shortened 1981 season were 46-56.

By 1982 the Pirates were showing their age. Although they finished with a winning record of 84-78, some of their players, most notably Robinson (39) and Willie Stargell (42) were getting old. On June 15, 1982, Robinson and his .239 batting average were traded to the Phillies for Wayne Nordhagen. As Robinson parted with the Pirates, Stargell said, “Bill Robinson is one helluva man, nothing but a plus in anybody’s life. He is a caring, concerned man.27

In the remaining months of 1982, Robinson played in 35 games for the Phillies, batting .261 (18-for-69). He saw his last action in 1983, getting into only 10 games, and was released on May 23. Teammate Mike Schmidt remembered back to 1972 when he was at Eugene, Oregon, his last stop in the minors, and was teamed with Robinson. Schmidt remembered that Robinson “respected me as a player, and knowing that made me feel good. He kind of took me under his wing. … (J)ust a good friend, a guy that had been there before. … Robbie is a credit to the game of baseball. I don’t know how to put it any other way.”28 Robinson finished his 16-year major-league playing career with a .258 batting average, 166 home runs and 641 RBIs.

In his last weeks with the Phillies, Robinson took the time to counsel rookie pitcher Charles Hudson on the importance of relaxing, and learning to “alleviate pressure.”29 He would spend the better part of his remaining years instilling that lesson on a new generation of players.

In 1984 Robinson joined the New York Mets as hitting instructor and first-base coach, and “Uncle Bill” was with the Mets for six years during which time the team never finished lower than second place. Robinson got his second World Series ring in 1986, and was a valued instructor working with the likes of Darryl Strawberry, who became his special project.

Ron Darling was in his first full season with the Mets in 1984, and on August 7 pitched against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. By day’s end, he would know first-hand the value of Bill Robinson to the New York Mets. Darling was pulled from the game not long after hitting Dave Owen of Chicago in the fifth inning. An irate Cubs fan threw a cup of beer at Darling as he left the field. Darling was about to go back on the field and pursue his attacker when Robinson grabbed hold of him and set him down. Robinson, of course, could display his temper, and was about to pursue the fan. He backed off when the fan was escorted from the premises by security guards. When Robinson returned to the dugout, he shot a knowing glance in Darling’s direction, which the young pitcher took as a much needed sign of encouragement.30

Robinson looked for every edge for his players, and was quick to accuse Pirates pitcher Rick Rhoden of doctoring the ball in a game against the Mets on July 6, 1986, in Pittsburgh. He confronted Rhoden after the pitcher struck out Gary Carter to end the fifth inning. A shoving match ensued and, before long, the benches cleared. Robinson was fined $500, but his players knew where he stood.

During the stretch drive in 1986, Robinson made it a point to put a picture in Strawberry’s locker of Darryl hitting a line drive, just to remind his star pupil how he looked when swinging well.31 During the last 11 games of the regular season, Strawberry batted .306 with 6 home runs and 15 RBIs. During his six years working with Robinson, Strawberry averaged over 30 home runs per season.

During the 1986 World Series, Robinson spoke of the challenges he faced with the Mets and the approach he had taken. “I think that with these young kids, you’ve got to be more than a hitting instructor. I’m not their father but you’ve got to give them fatherly street advice. It certainly helps me, not only being black, but talking to all the guys it helps a lot that I have a son who is the same age as most of these guys. I respect them all and think they respect me. They’re trying to get where I’ve been.”32 Bill’s son at the time became very close with Strawberry and Dwight Gooden. Every time Gooden had an issue, he was able to come to Robinson, who was much more than a hitting instructor.

And on that magical (for the Mets) evening in October, Bill Robinson was standing in the first-base coaching box when, in that fateful bottom of the 10th inning of Game Six of the World Series, every player got the low two when he arrived at first base. The rallying cry was “Don’t make the last out!”33 And then, Mookie Wilson hit a groundball in the direction of first base. “It made three nice bounces. Bounce … bounce … bounce. And then it hit something and didn’t come up again. That fourth bounce. It was just our year.”34 Wilson remembered that during that fateful bottom of the 10th inning, each of the Mets involved in the rally told Robinson that they were not determined to make the last out.35

The Mets were unable to build on the success of 1986, and in 1989 after finishing in second place, six games behind the division-winning Cubs, Robinson was fired. After spending two years with ESPN, in 1992 he took a managing job at Shreveport in the Double-A Texas League and led the Giants affiliate to the championship with a 77-59 record. He was frustrated at not being given an opportunity to rise higher, as he aspired to eventually get a major-league managing position. He did feel that race had something to do with his not moving higher, stating: “If (becoming a big league manager) doesn’t happen, it won’t surprise me. Whether it’s prejudice, whether it’s timing, or whatever, it’s always excuses.”36

Robinson’s next stop was back with the Phillies, as a minor league hitting instructor in 1994, and as manager at Reading in the Eastern League in 1996. The following season he moved up to Triple-A Scranton-Wilkes-Barre as hitting instructor, and was inducted into the Pennsylvania Baseball Sports Hall of Fame.

Robinson was doing what he loved. In 1998 he said, “It’s been fun, gratifying to help young kids. I had delusions of being a major-league manager, but I know that’s not going to happen. Baseball doesn’t owe me a thing. As long as I have a uniform on, I’m grateful. I’ve been successful. Maybe not in a material way, but I have the Lord on my side and my family. What more could a man ask?”37

In 1999 Robinson was back in the Yankees organization, working with the hitters at Triple-A Columbus. He was rewarded for his efforts with a World Series ring when the Yankees won the championship that year. He stayed with Columbus for three years before returning to the majors as the hitting instructor for the Montreal Expos in 2001.

Robinson was ecstatic about returning to the big leagues as a coach. “I had waited 12 years to get back to the major leagues. After I accepted (the offer from Expos manager Jeff Torborg), I walked out on Madison Avenue (in New York), raised my hands to the sky, and said, ‘Thank God.’”38

In 2003 Robinson was with the Florida Marlins and returned to the World Series, facing the Yankees and winning his fourth World Series ring as the Marlins defeated the Yankees. George Vecsey of the New York Times perhaps summed things up the best: “Whether (the Marlins) know it or not, their paternal hitting coach is an inspiration for athletes — or anybody else who has a bad day or a bad couple of years. You can come back. You can go from failure to the World Series.”39

Robinson died suddenly on July 29, 2007, in Las Vegas while working as a minor-league hitting coordinator for the Los Angeles Dodgers. He was survived by his wife, Mary Alice, and their two children. William III played three years of minor-league baseball before moving into broadcasting, and Kelley worked in the fashion industry.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted:

Vecsey, George. “And Here’s To You Mr. Robinson, My Friend,” New York Times, August 2, 2007: D-1.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Robinson’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame library.

Notes

1 Jim Kaplan, “He’s an Irregular Regular,” Sports Illustrated, April 25, 1977

2 Kaplan.

3 Baseball-reference.com lists Robinson at 6-feet-2 and 189 pounds.

4 Kaplan.

5 Kaplan.

6 Jack Chevalier, Philadelphia Tribune, September 19, 2003.

7 The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 42.

8 Furman Bisher, “Robby Came for Cup of Coffee, Stayed to Feast with Crackers,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1965: 37.

9 Sam Smith, “Bill Robinson, In Search of Confidence,” Black Sports, September, 1974: 23.

10 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees from Before the Babe to After the Boss (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 368.

11 Smith, 31.

12 Neil Amdur, “Robinson of Yanks Is Relaxed for His Second Time Around,” New York Times, April 8, 1968: 67.

13 Appel, 378.

14 Ed Rumill, “Phillies Robinson Glad He Didn’t Quit,” Christian Science Monitor, June 27, 1973.

15 Smith, 47.

16 Kaplan.

17 Kaplan.

18 Kaplan.

19 Kaplan

20 Kaplan

21 Charlie Feeney, “Robinson Snubbed as All-Star, Glistens as Buc,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1977: 15

22 Charlie Feeney, “Lucky Bucs Find Robinson Can Do Job on Daily Basis, The Sporting News, August 13, 1977: 8.

23 Pittsburgh Pirates Press Release, August 15, 1977, in Robinson file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

24 Charlie Feeney, “Bucs Waiting For Robinson to End Slump,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1978: 28.

25 Feeney, “Bucs Cash in on Robinson’s Waiting Game,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1979: 17.

26 Charlie Feeney, “Bucs Get No Nibbles With Robinson as Bait,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1979: 61.

27 Frank Dolson, “Baseball Can’t Lose People Like Robinson,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1983: 7-C.

28 Dolson.

29 Dolson.

30 Ron Darling with Danie Paisner, The Complete Game (New York: Random House, 2009), 133-34.

31 Jim Naughton, New York Daily News, October 5, 1986.

32 Malcolm Moran, “Robinson and His Gifted Student,” New York Times, October 23, 1986: B16.

33 Interview with Bill Robinson III, June 2015.

34 Vic Ziegel, “Robby Back Where He Belongs,” New York Daily News, March 27, 1998.

35 Mookie Wilson (with Erik Sherman), Mookie: Life, Baseball, and the ’86 Mets, (New York: Berkley Books, 2014), 6.

36 Taylor Batten, Associated Press, “Is There Racism in Baseball?” Mobile (Alabama) Register, July 22, 1992: 26.

37 Ziegel.

38 Jack Chevalier, Philadelphia Tribune, November 13, 2011: 2C

39 George Vecsey, “Ex-Yankee Robinson Returns as a Winner, New York Times, October 20, 2003: D-4.

Full Name

William Henry Robinson

Born

June 26, 1943 at McKeesport, PA (USA)

Died

July 29, 2007 at Las Vegas, NV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.