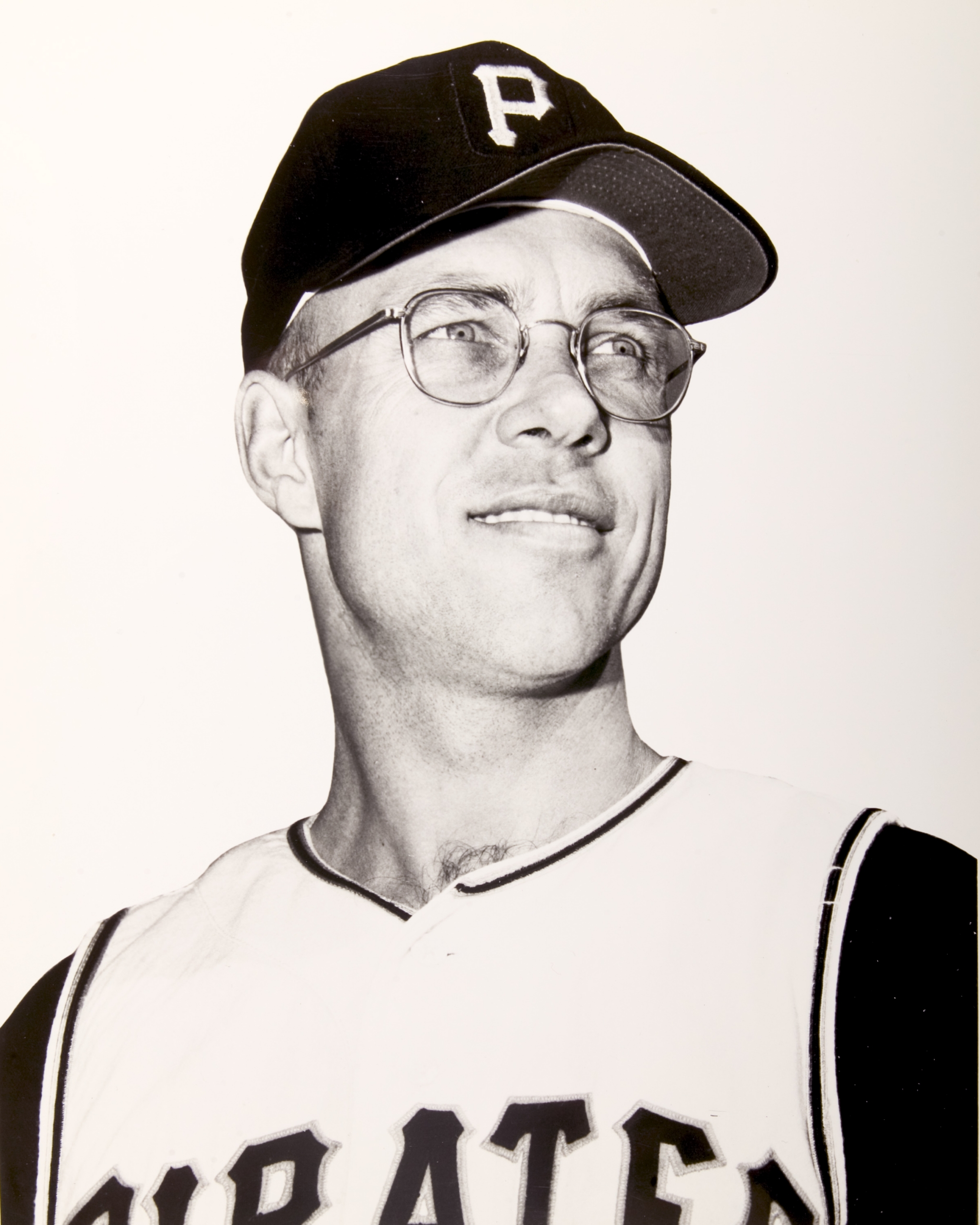

Bill Virdon

From 1955 to 1965 Bill Virdon established his reputation as one of the finest and fastest center fielders of his generation, and was known for his accurate throws from the deep center-field power alleys in spacious Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Ironically, one of his throws that inadvertently hit his manager may have led to his biggest break in baseball.

From 1955 to 1965 Bill Virdon established his reputation as one of the finest and fastest center fielders of his generation, and was known for his accurate throws from the deep center-field power alleys in spacious Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Ironically, one of his throws that inadvertently hit his manager may have led to his biggest break in baseball.

Having toiled in the New York Yankees farm system since 1950, Virdon was at his first Yankees spring training in 1954, but his prospects seemed dim. “I could see that I was going to have a problem breaking in on the Yankees,” Virdon said. “They had the best outfield in baseball.”1

Indeed, the Yankees, coming off five consecutive World Series championships, had Hank Bauer and Gene Woodling in right and left respectively and Mickey Mantle in center. Like Mantle, Virdon was 23 years old; however, Virdon was fighting for his professional career.

Near the end of camp he was in the outfield with Bauer, Woodling, and Mantle practicing. “I fielded a fly ball and fired away,” Virdon remembered. “Somehow Mr. Stengel got between me and the relay man and I proceeded to hit him in the back with my strongest throw and knocked him down. The other outfielders were laughing and pointing to me: ‘He did it.’ Mr. Stengel got up, shook himself and hollered, ‘If you guys throw like that in a game, you might throw someone out.’ ” With a chuckle, Virdon added, “Two weeks later I was traded.”

The trade sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals and the next year he was named the National League Rookie of the Year for 1955. “The trade came somewhat as a surprise,” Virdon said, “but at that point it was probably the biggest break I got in baseball.”

William Charles Virdon was born on June 9, 1931, in Hazel Park, Michigan, to Charles and Bertha Virdon, who had migrated from southern Missouri during the Depression to find work in the automobile factories around Detroit. When Virdon was 12 his family returned to Missouri and settled in West Plains, near Springfield. An avid softball player, his father ran a country store and his mother was a homemaker.

Quick and agile, Bill was an excellent athlete at West Plains High School, where he excelled in track, basketball, and football; the school did not field a baseball team. Although he played in informal leagues, his first opportunity to play organized baseball came in the summer of 1948, after his junior year. Persuaded by his friend Gene Richmond to travel almost 300 miles to Clay City, Kansas, to try out for the local AABC (American Amateur Baseball Congress) team, Virdon made the team as a shortstop and was then moved to center field because of his athleticism.

Though Virdon was far from home for the 50-game season, his parents were supportive. “I went to a tryout camp for the Yankees in Branson, Missouri, following my senior year,” Virdon remembered. “And after that I went back out to play ball in Kansas.” When the season ended Virdon returned to Branson and Yankees scout Tom Greenwade, who had signed Mantle a year earlier, signed Virdon for a $1,800 bonus.

Virdon began his professional career with the Independence (Kansas) Yankees of the Class D Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri (KOM) League in 1950, where he was managed by Malcolm “Bunny” Mick. Virdon called Mick “one of the big influences in my career,” adding, “He was an outfielder and knew all about playing. He pushed me.” Still learning to play center field, Virdon was promoted after the season to the Yankees’ Triple A team, the Kansas City Blues in the American Association, and hit .341 in 14 games. “The reason I was promoted was Bunny Mick,” he said. “He got fired in Independence at the end of the year and ended up going to Kansas City to play. He told them about me and they brought me up.”

Despite Virdon’s light hitting and lack of power in 1951 with the Norfolk Tars in the Class B Piedmont League and in 1952 with the Binghamton Triplets of the Class A Eastern League (.286 and .261 respectively), the Yankees were impressed enough by his fielding to invite him to the Yankees’ pre-camp in Arizona in 1953, where he had the chance to work with the team’s top prospects, and then promoted him again to the Kansas City Blues in 1953.

This team was loaded with future major-league talent, including Bob Cerv, Elston Howard, Vic Power, and Bill Skowron, all of whom played or could play the outfield. Though Virdon excelled in the field, he struggled at the plate, hitting just .233, and was demoted to the Birmingham Barons of the Double-A Southern Association.

“I was disappointed about the demotion but that is part of the business,” Virdon said. “I went down and I actually finished the season with a pretty good record.”

Indeed he did. Rooming with future Pirate Hal Smith, Virdon batted .317 in 42 games. His success at the plate may have been due to a different approach. “He started improving his hitting,” Smith said, “because he wasn’t trying to hit a home run and learned how to hit line drives to all fields.”2

After being dispatched to the Cardinals with two other players in a trade for All-Star Enos Slaughter in the spring of 1954, Virdon was sent to St. Louis’s Triple-A team, the Rochester Red Wings of the International League. He got off to a torrid start and in mid-June The Sporting News wrote that “Virdon now appears to be the best bargain since Manhattan Island.”3 He finished with 22 home runs and a league-leading .333 batting average and was second in the International League’s MVP voting behind former minor-league teammate Elston Howard. “That was the best year I ever had,” Virdon said. He was considered the second-best prospect in all of minor-league baseball behind Howard.4 Throughout his career, one of Virdon’s defining characteristics was his round, wire-rimmed eyeglasses, which he credited for his improved hitting in 1953 and 1954.

After the 1954 season Virdon continued his hot hitting for the Havana Lions in the Cuban League, the only time he ever played winter ball. Lions manager Dolf Luque was impressed with his hitting and Cardinals Cuban League scout Gus Mancuso declared, “This kid Virdon does amazing things in center field”;5 and by January 1955 Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky already had ideas to move Stan Musial from the outfield to first base in order to make room for Virdon in the starting lineup.6 Finishing the season with a .340 batting average and as a Cuban League all-star, Virdon commented, “I felt like playing in Cuba was one of the best things I ever did in baseball. It was just a time to develop. I got to face excellent pitching and it was the easiest league I ever played in because you did not travel.”

Given Country Slaughter’s number 9, Virdon followed a poor spring with a hot start to the season. Stanky rearranged his outfield by moving Wally Moon, the 1954 NL Rookie of the Year, from center to right and Virdon was given center field. Musial was moved from right field to first base. Longtime Cardinals beat reporter Bob Broeg wrote “[Virdon] is a solid ballplayer with no apparent weakness.” Though the Cardinals floundered and finished seventh, ahead of only the Pirates, Virdon was named Rookie of the Year for his all-around performance: He hit well (.281) and fielded exceptionally. Club President August Busch Jr. called the trade for Virdon “one of the best deals we ever made.”7

Busch wanted immediate success and brought in Frank “Trader” Lane as the new general manager at the end of the 1955 season. Lane had made his reputation with the Chicago White Sox over the previous decade and was known for his propensity to trade players. Even after another slow spring, in which he batted below .200, Virdon was undeterred, saying, “A year up here gives you confidence and I believe in myself.”8

However, his slump continued into the season, and that was all Lane needed. Claiming he had too many left-hand hitters and “Bill wasn’t hitting the ball that hard,”9 Lane traded Virdon to the Pirates on May 17 for light-hitting center fielder Bobby Del Greco and journeyman pitcher Dick Littlefield. “I was a Missouri and Cardinals guy,” Virdon said, “and hated to go.” Two months later it was clear that the trade was a phenomenal success for the Pirates.

The trade for Virdon was the first deal for the new Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown, who had joined the Bucs’ front office in November 1955 and succeeded Branch Rickey when he stepped down as general manager. The Pirates had long coveted Virdon and in 1954 Rickey had offered the Yankees pitchers Vern Law and Max Surkont in exchange for him, but was rebuffed.10

In 1956 Virdon arrived on a team defined by a culture of failure. The Bucs had not had a winning record since 1948 and had finished in last place four consecutive years and five of the last six. “It wasn’t the brightest thing in the world,” Virdon said of his trade. “Pittsburgh had been losing for years.” But he noticed more than just losing: “I could see that Pittsburgh had some talent.” The Pirates were a young team: shortstop Dick Groat was 25; rookie second baseman Bill Mazeroski was 19, and in the outfield Roberto Clemente just 21 and Virdon 25.

On June 16 the Corsairs won their 30th game (against 21 defeats), the earliest they had reached 30 wins since 1945.11 The Sporting News ran the headline “The Bucs Turn Pittsburgh Into Boom Town”12 as fans flocked to Forbes Field. Though the Bucs ultimately finished in seventh place, the hot start revealed the team’s potential. After his trade, Virdon hit at a .334 clip and battled Hank Aaron for the batting title, finishing second with a .319 average, the only time in his career that he batted over. 300.

Because of Virdon’s many soft infield bloop hits, Pirates radio announcer Bob Prince tabbed him “Quail,” a nickname that stayed with him his entire playing career. Virdon exceeded expectations and was lauded as the “brightest star” and “best all-around player of the team,”13 while the outfield trio of Virdon, Clemente, and Lee Walls was judged the best in baseball.14

With the team floundering with a 36-67 record in 1957, general manager Joe L. Brown made a move that profoundly impacted the Pirates’ and Virdon’s future: he hired as manager Danny Murtaugh, who then skippered the Bucs to a 26-25 record to close out the season. “Murtaugh knew when to talk, when to correct, and when to discipline,” Virdon recalled. “He just seemed to know the right thing to do for a winning ballclub.” Murtaugh changed the culture in Pittsburgh and stressed fundamentals. “He pushed me,” Virdon said, “and made sure that I got all of the instruction that I should get.”

Virdon had an inclination to teach baseball (he operated his first baseball school in the 1956 off-season15) and Murtaugh encouraged him to follow his coaching passion. Virdon first coached in the Arizona Instructional League after the 1962 season and in the Florida Instructional League in 1964, at which time he was already being touted by The Sporting News as “the best managerial talent” on the Pirates.16

Patrolling center field in Forbes Field for ten seasons (1956-1965), Virdon was durable, never suffered a debilitating injury, and was never placed on the disabled list. After hitting .319 in 1956, his second year in the major leagues, Virdon remained a consistent .260s-hitter the rest of his career. Forbes Field no doubt affected his power; after hitting 17 home runs as a rookie, he tallied just 74 more in his career. In the late 1950s, the left-handed-hitting Virdon was considered with Mickey Mantle and Bill White one of the fastest players from home to first base while batting (3.5 seconds) or bunting (3.4 seconds).17

Batting leadoff for much of his career, Virdon used his speed and the dimensions of Forbes Field to rack up triples, leading the league once. When Murtaugh was asked if he was concerned about Virdon’s career-low .243 batting average in 1964, he answered emphatically, “I count the hits he takes away from others as part of his batting average.”18 His cerebral approach to baseball meant that Virdon’s value to the Pirates could not be reduced to batting statistics.

“He’s an underrated player,” Roberto Clemente said of Virdon. “He doesn’t get the headlines because he makes everything look easy. He’s kept a few of our pitchers in the majors with his glove and hitting.”19 Virdon had a quiet and reserved demeanor, didn’t seek headlines, and was overshadowed playing center field in a league that featured perhaps the greatest center fielder of all time in Willie Mays and playing next to perhaps the best right fielder of all time in Clemente.

“Virdon wasn’t as flashy as Willie Mays,” said teammate Bob Friend. “Forbes Field was a big ballpark and Virdon could play short and cover everything. There wasn’t a better center fielder in my era.”20

He was regularly among the league leaders in putouts and assists, leading the league in 1959 with 16. Bill James’s “range factor,” a metric used to evaluate the quality of defensive play, underscores that Virdon was easily one of the best outfielders of his generation; he led the league twice (1959 and 1961) in the statistic. At the age of 31 Virdon won his first and only Gold Glove award in 1962 a year after voting was revamped to award the top three outfielders instead of a position-specific format (RF, CF, LF).

“Bill has made amazing fielding plays so common in Forbes Field,” Dick Groat wrote, “that Pirate fans are inclined to be disappointed if he doesn’t catch everything hit to the outfield.”21 Virdon studied hitters’ habits and tendencies and used his speed to neutralize the enormous power alleys at Forbes Field. “Virdon got such great jumps on the ball,” teammate Hal Smith said. “He knew exactly where the ball was going.”

“It was the biggest in baseball,” Virdon said about Forbes Field. “I didn’t have to worry about running into the fences.” With its irregular shape, Forbes Field was 435 feet to the center-field wall, 457 to left-center, and 419 to right-center, which played to Virdon’s strengths: speed and arm strength.22 The field was so big that “the batting cage was in left-center field,” Virdon remembered. “There was a big light pole that sat inside the ballpark and it had a fence around it. The batting cage was next to this fence. It wasn’t really that obvious. The ballpark was so big that I played in it for ten years and I don’t think the batting cage came into play more than three or four times.”

The 1960 season was a magical one for the Pirates, but it began with concern and lingering doubts. After Murtaugh guided the team to 84 wins and a surprising second-place finish in 1958, the Bucs slipped to fourth in 1959. The team sold Forbes Field to the University of Pittsburgh in 1959 and team president John Galbreath had to squash rumors that the franchise would relocate as the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants had done two years earlier.

To add to the core players such as Clemente, Groat, Mazeroski, Virdon, Bob Skinner, Dick Stuart, and pitchers Elroy Face, Vern Law, and Bob Friend, Brown made wise trades for Smoky Burgess, Harvey Haddix, Don Hoak, and Rocky Nelson in 1959 and for Gino Cimoli, Vinegar Bend Mizell, and Hal Smith in 1960. But one trade Brown attempted failed: He offered the Kansas City Athletics Virdon, Groat, and Ronnie Kline for slugger Roger Maris.23

“We all played for a pennant,” Virdon said of the 1960 season, “and we thought we had a chance to do it.” Virdon’s optimism was tempered by the public perception of the Pirates; in national polls, sportswriters and players picked the Pirates to come in no better than fourth, behind the Braves, Dodgers, and Giants.24

“The 1960 season was unbelievable,” Virdon said. “It seemed like every time we needed a run in a crucial situation, we got it.” The team was known for manufacturing runs and playing “small ball” in an era of home runs. The Pirates led the league in hitting, runs, and OPS (on-base average plus slugging average), and ranked second in slugging while hitting only 120 home runs (sixth in the NL). “We were scramblers” said Virdon, who was platooned with Cimoli. In 1960 Murtaugh rested Virdon against left-handed pitchers; thus he started only 98 games in center field.

The 1960 World Series will forever be defined by Bill Mazeroski’s Series-winning home run, but Bill Virdon’s inspired fielding, his speed, and his uncanny knack for timely hitting were keys to the Pirates’ victory. “Virdon was the guy who really hurt the Yankees,” Friend said, and it started in the bottom of the first inning of Game One. Virdon and his roommate, Groat, who were considered among the best at the hit-and run, had a chance to execute their specialty when Virdon walked to lead off the game.

“When I got to first base I looked to Groat for the hit-and-run” Virdon said, “and he put it on. Dick didn’t realize that he had put the hit-and-run on by mistake and tried to take it off, but I didn’t bother to look at him again.” Virdon took off and Groat took [Art] Ditmar’s pitch. “Yogi saw that I was running” Virdon recollected, “and threw the ball to second, but nobody was covering. So I moved on to third.” The Pirates went on to score three runs and ultimately won, but more importantly that first inning set the tone for the Series.

Virdon’s fielding, hailed as “brilliant,”25 choked Yankee rallies throughout the series. With Law struggling in Game One, Berra hit a deep shot to right-center field with two on in the fourth inning. Virdon chased down the ball and made a tremendous catch at the 407-foot marker while colliding with Clemente and saved two runs.

The fielding highlight of the Series may have been Virdon’s acrobatic catch of Bob Cerv’s deep fly ball in the seventh inning of Game Four with two men on and the momentum shifting in favor of the Yankees. “I thought I was closer to the fence than I really was,” Virdon said. “I wanted to make sure I caught the ball before I hit the fence so I jumped.” Dan Daniel wrote afterward, “He [Virdon] won the opener with his fielding and hitting, and he did it again in the fourth game.”26

In the bottom of the eighth inning of Game Seven, Virdon was involved in one of the most famous “what if?” plays in professional sports. With the Pirates trailing 7-4 and Gino Cimoli on first, Virdon hit what appeared to be a routine double-play ball to shortstop Tony Kubek. Forbes Field had a notoriously hard infield (Bucs announcer Bob Prince called it the “House of Thrills” because of the odd hops).

“When I hit the ball,” Virdon said, “I knew it was a double play all the way. The ball took a bad hop and hit Tony in the throat.” Kubek was taken to the hospital. Instead of two outs and the bases empty, there were two on with no outs and the Bucs rallied with five runs, culminating with Hal Smith’s three-run homer. The Yankees tied it in the ninth and the rest is history. Despite going only 7-for-30 in the Series, Virdon was one of the heroes of the Pirates’ unlikely championship.

Though the Pirates played sub-.500 ball in three of the next four years, Virdon remained an excellent fielder and an integral part of the team. But after the 1964 season, he said, “I could feel myself slipping a little. . . . As you get older, playing every day is a mental problem.”27 His reaction probably referred to a few uncharacteristic lapses in concentration in the field but also pointed to his intention to start coaching. “I planned on quitting in 1965,” he said, “and told the Pirates it would be my last year.”

Though the Pirates played sub-.500 ball in three of the next four years, Virdon remained an excellent fielder and an integral part of the team. But after the 1964 season, he said, “I could feel myself slipping a little. . . . As you get older, playing every day is a mental problem.”27 His reaction probably referred to a few uncharacteristic lapses in concentration in the field but also pointed to his intention to start coaching. “I planned on quitting in 1965,” he said, “and told the Pirates it would be my last year.”

Virdon, who always held himself to the highest standards, put the Pirates’ concern before his own, and with little fanfare he retired after the 1965 season. “I could probably hang on for a few years,” he said. “But I don’t want to be a hanger-on.”28 The “Quail” finished with 1,596 hits, 735 runs, and a .267 batting average in 1,583 games, but also as one of the most underrated players of his generation.

Virdon’s managerial career began just weeks after his unconditional release and retirement on November 22, 1965, but not the way he had envisioned. “I was encouraged by Murtaugh to go into coaching,” he said. “I decided to stay in baseball and I had an opportunity to manage in the Pirate organization. But at that point the pay for managing in the minor leagues was not too good. So I shopped around and found a job in the Mets organization.” After managing for two years in the Mets organization, Virdon returned to the Pirates under new manager Larry Shepard. While a coach for the Bucs in 1968, he was placed on the active roster due to the military service of many players. He played in six games and his only hit was a two-run home run, the last hit of his career.

When Shepard was fired with five games left in the 1969 season, many assumed Virdon would get his first shot to manage, but he was bypassed in favor of Alex Grammas and then passed over again to start the 1970 season when Murtaugh came back for his third stint with the Bucs. Though he thought he was ready to be a major-league manager, Virdon refused to criticize general manager Joe Brown or the Pirates organization for any perceived slight. After the Pirates won the World Series in 1971 and Murtaugh retired for the third time, Virdon finally got his chance to manage.

After managing the San Juan Senators in the Puerto Rican league following the 1971 season, Virdon guided the Pirates to a first-place finish in 1972 only to lose a heartbreaking Game Five to Cincinnati in the National League Championship Series when Bob Moose threw a wild pitch that allowed George Foster to score the winning run in the bottom of the ninth. Virdon was fired with 26 games to play the next season even though the Pirates were just three games out of first place (though they had a losing record).

Under bizarre circumstances, Virdon was hired by George Steinbrenner to manage the Yankees in 1974 just two months before the season began after A’s owner Charlie Finley refused to allow Dick Williams out of his contract to manage the Yankees. Virdon kept the light-hitting Bronx Bombers in the fight for the American League East crown all season and they finished just two games behind Baltimore. Having led the Yankees to their closest pennant race since 1964, Virdon won his first of two Sporting News Manager of the Year awards.

Despite his self-effacing personality and calm demeanor, Virdon was a competitive, no-nonsense manager who stressed fundamentals and demanded that his players put the team above individual reward. This led to high-profile confrontations with Dock Ellis, Richie Hebner, and Bobby Murcer. “I just tried to be honest and fair and made sure that everyone played hard,” Virdon said of his coaching philosophy. “I did not put up with too much. [I was a disciplinarian] to some extent but without being offensive.” In 1975 the Yankees failed to match their success of the previous year and Virdon was fired with a 53-51 record. Weeks later the Houston Astros hired him.

Virdon managed in Houston until 1982 and won his second Manager of the Year award after leading the Astros to their first postseason berth and to the brink of the World Series in 1980, only to lose another gut-wrenching Game Five of the NLCS, this time in extra innings. His managerial career concluded in 1984 after a two-year stint with the Montreal Expos. Despite his winning record (995-921) and rumors of being the next manager for a number of teams, he never skippered a team again. From 1985 until his retirement after the 2001 season, Virdon was a coach for the Pirates under Jim Leyland and Lloyd McClendon, as well as a minor-league instructor. He also coached for the Astros and in the Cardinals minor-league system.

With Shirley, his wife of almost 60 years, Virdon still resided in southern Missouri in his final years. A baseball lifer, Virdon remained active with the Pittsburgh Pirates. “The best part of my career,” he said before departing for the Pirates’ spring-training camp in 2012, “is that I have not missed a spring training in 62 years!”

Virdon died at the age of 90 on November 23, 2021.

Sources

Statistics are from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

David Cicotello and Angelo J. Louisa, eds., Forbes Field. Essays and Memories of the Pirates Historic Ballpark, 1909-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2007).

Rick Cushing, 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates Day by Day: A Special Season, An Extraordinary World Series. (Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing Co., Inc., 2010).

David Finoli and Bill Ranier, eds. The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003).

Dick Groat, The World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: Coward-McCann, 1961).

David Maranis, Clemente: The Pride and Passion of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).

Richard Peterson, ed., The Pirates Reader (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003).

Jim Reisler, The Best Game Ever: Pirates vs. Yankees October 13, 1960 (Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2007).

Notes

1 The author would like to express his gratitude to Bill Virdon, who was interviewed for this biography on January 12, 2012. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Virdon are from the author’s recorded interview.

2 The author would like to express his gratitude to Hal Smith, who was interviewed for this biography on February 7, 2012. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Smith are from the author’s recorded interview.

3 The Sporting News, June 16, 1954, 16.

4 The Sporting News, November 3, 1954, 13.

5 The Sporting News, December 29, 1954, 25.

6 The Sporting News, January 19, 1955, 11.

7 The Sporting News, October 12, 1955, 2.

8 The Sporting News, March 28, 1955, 26

9 The Sporting News, May 23, 1956, 6.

10 The Sporting News, December 15, 1954, 16.

11 All game statistics have been verified by Retrosheet (www.retrosheet.com).

12 The Sporting News, June 13, 1956, 5.

13 The Sporting News, August 1, 1956, 1; and September 5, 1956, 15.

14 The Sporting News, August 1, 1956, 9, 14.

15 The Sporting News, September 5, 1956, 15.

16 The Sporting News, April 25, 1964, 12.

17 The Sporting News, November 28, 1956, 3.

18 The Sporting News, November 7, 1964, 11.

19 The Sporting News, June 29, 1963, 14.

20 The author would like to express his gratitude to Bob Friend, who was interviewed for this biography on March 6, 2012. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Friend are from the author’s recorded interview.

21 Dick Groat, The World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: Coward-McCann, 1961), 154.

22 Ronald M. Selter, “Inside the Park: Dimensions and Configurations of Forbes Field,” in David Cicotello and Angelo J. Louisa, eds., Forbes Field. Essays and Memories of the Pirates Historic Ballpark, 1909-197. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co, 2007), 132.

23 The Sporting News, December 21, 1960, 26.

24 Groat, 93.

25 The Sporting News, October 19, 1960, 10.

26 Ibid.

27 The Sporting News, December 25, 1964, 25.

28 The Sporting News, December 6, 1965, 24.

Full Name

William Charles Virdon

Born

June 9, 1931 at Hazel Park, MI (USA)

Died

November 23, 2021 at Springfield, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.