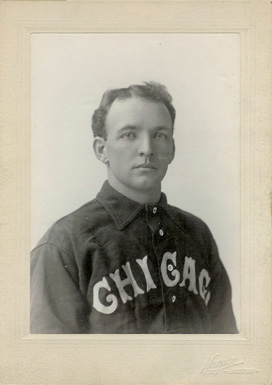

Billy Sullivan Sr.

Though “never very strong in stick work,” his Deadball Era contemporaries believed that Billy Sullivan’s “brilliant performances behind the bat … more than offset his weak hitting.” Although his paltry .213 lifetime batting average is the second worst all-time (next to Bill Bergen) among players with at least 3,000 at bats, Sullivan developed a reputation as a brainy backstop with an uncanny ability to handle pitchers. Described by Ty Cobb as the best catcher “ever to wear shoe leather,” Sullivan was “the best man throwing to bases in the American League,” and “no man in the business [knew] more about getting the best work from a pitcher and holding an infield together.” Sullivan also revolutionized the way his position was played; he is credited as the first catcher to position himself directly behind the batter and as the inventor of an inflatable chest protector.

Though “never very strong in stick work,” his Deadball Era contemporaries believed that Billy Sullivan’s “brilliant performances behind the bat … more than offset his weak hitting.” Although his paltry .213 lifetime batting average is the second worst all-time (next to Bill Bergen) among players with at least 3,000 at bats, Sullivan developed a reputation as a brainy backstop with an uncanny ability to handle pitchers. Described by Ty Cobb as the best catcher “ever to wear shoe leather,” Sullivan was “the best man throwing to bases in the American League,” and “no man in the business [knew] more about getting the best work from a pitcher and holding an infield together.” Sullivan also revolutionized the way his position was played; he is credited as the first catcher to position himself directly behind the batter and as the inventor of an inflatable chest protector.

William Joseph Sullivan was born on a farm near Oakland, Wisconsin, on February 1, 1875, the son of Irish immigrants. He first displayed his potential as a ball player at Fort Atkinson High School, where he starred in the infield. As a high school student, Sullivan played shortstop until an accident disabled his team’s regular catcher. Without any previous experience, the young Sullivan was put in to catch, where his work behind the bat attracted the attention of the local town team’s manager. Afterward, he caught for an independent team in Edgewater, Wisconsin, before he broke into the professional ranks with the Western Association’s Cedar Rapids Bunnies in 1896. The next year, the 5’9″, 155-pound right-hander played for Dubuque in the same league, managed by Joe Cantillon. Purchased from Dubuque by Tom Loftus, Sullivan worked behind the plate for Columbus (Ohio) of the Western League in 1898. The next year he was transferred with his team to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he hit .306 in 83 games before being sold to the Boston Beaneaters at the end of the season. Catching 66 games for Boston in 1900, Sullivan slugged eight home runs, fifth in the National League. It was the only time in his career he would make the top ten in any hitting category.

Before the 1901 season, an offer of $2,400 enticed him to jump to the White Sox, where he caught the American League’s first game as a major league, Chicago’s 8-2 victory over Cleveland on April 24, 1901. Despite his impressive hitting for the Beaneaters in 1900, once in American League company Sullivan’s offense quickly disappeared, as it did for most of the era’s backstops. He batted .245 in his first season with the White Sox, a pedestrian average that would prove to be the highest of his American League career. From 1903 to 1912, he never batted higher than .229 in any season, and finished as low as .162. His abysmal hitting was coupled with a shortage of power and an inability to get on base via other means–for his career he finished with a .254 on-base percentage and a .281 slugging percentage. Sullivan was particularly dreadful in his only postseason appearance. In the 1906 World Series against the Chicago Cubs he went hitless in 21 at-bats, including nine strikeouts. However, he caught every inning of every game and guided his pitchers to a collective 1.33 ERA in the Sox’ six-game victory.

Somehow, the White Sox seemed a better team with the scrappy, resourceful Sullivan in their lineup. With Sullivan as their primary catcher, the White Sox won two pennants (1901 and 1906) and narrowly missed two others (1905 and 1908) while never finishing lower than fourth place. By contrast, in the two seasons in which he was injured, 1903 and 1910, the club finished in the second division both times, more than 30 games out of first place. During his years in uniform, Sullivan was particularly important in steadying Chicago’s stalwart pitching rotation, which included the likes of Ed Walsh, Doc White, and Nick Altrock. Four times a league-leader in fielding percentage, Sullivan placed himself directly behind the batter. In 1908 Sullivan was issued a U.S. Patent for an inflatable, contoured chest protector, which protected his body better and, thanks to hinging, allowed more freedom of movement than the normal model.

On October 24, 1905, Sullivan married Mary Josephine O’Sullivan, who had emigrated from Ireland five years earlier. The marriage lasted 24 years until her death in January 1930. A clean-living player who didn’t swear, drink, or smoke, Sully replaced Fielder Jones as Chicago’s playing manager in 1909, piloting the club to a 78-74 record and a fourth-place finish. It was Sullivan’s only season as manager; the next year, Hugh Duffy took the helm and Sully returned to catching full time.

On August 24, 1910, Sullivan caught three baseballs thrown by Ed Walsh off the top of the Washington Monument as a publicity stunt, duplicating Washington catcher Gabby Street‘s feat from two years earlier. Contemporary reports estimated that the balls sped at 161 feet per second toward Sullivan’s pancake mitt. Remarkably, despite gusty winds, Sullivan caught three of the eleven balls Walsh threw. Following the stunt, Sully declined to attempt to catch a ball dropped from an airplane, saying he “might as well try to stop a bullet.”

Sullivan was often sidelined by injuries. An errant foul tip broke his throwing hand in 1901. The next year he required an emergency appendectomy. He was hit by a pitched ball in 1904 and knocked unconscious. During the 1906 pennant chase, he re-injured his throwing hand. Perhaps the most serious injury Sullivan faced was a battle with the blood poisoning he contracted in 1910, after stepping on a rusty nail during a spring training trip. Following the dubious advice of a quack physician, he received a nearly-lethal dose of turpentine and almost lost a leg before receiving appropriate medical care. “This Sullivan man is a real hero,” the Atlanta Constitution wrote after the 1908 campaign. “He begged permission to catch the final game in Cleveland although two rows of stitches had been removed from his right thumb only the day before… The nature of his injury must have made his work agony, but he stuck to his job.”

In 1912, with Sullivan’s performance and endurance declining, young backstop Ray Schalk emerged as his successor. Sullivan spent the 1913 and 1914 seasons as a Sox coach, assisting manager Nixey Callahan, teaching Schalk, and managing the B squad in spring training. Chicago owner Charles Comiskey had promised Sullivan lifetime employment with the team as a reward for his years of service, but broke that promise on February 15, 1915, when he unconditionally released the shocked Sullivan. After trying and failing to land a job as an AL umpire, Billy joined the Minneapolis Millers – managed by his old skipper Cantillon – where he coached, batted .215, and caught 105 games of “fine ball” as they won the American Association pennant. Released by Minneapolis at the end of the year, he only appeared in a single game as a player-coach with Detroit in 1916.

At the end of the 1916 season, the 41-year-old Sullivan accepted his release and retired to a twenty-acre apple, walnut, and filbert farm outside Newberg, Oregon, where he spent the rest of his life with his wife, Mary. During the 1917 season, Sully attempted to catch on with Portland of the Pacific Coast League and Seattle of the Northwestern League, but he was unsuccessful.

Upon his retirement, Sullivan paid tribute to four of the foremost pitchers he caught. According to Sully, “Kid Nichols, of the old Boston Nationals, possessed the greatest speed; Ed Walsh was the peer of the spit ball pitchers; Jim Scott tops all the curve ball experts, and for all-around mixing and slow ball delivery there never was a man who excelled ‘Doc’ White.”

Although his son Joseph, a second baseman and captain on the University of Notre Dame team, turned down an offer from the White Sox in order to pursue a law career, his son, Billy Jr., began his own twelve-year major league career with the White Sox in 1931, playing with Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, the St. Louis Browns, Detroit, Brooklyn, and Pittsburgh. When Billy caught for Detroit in the 1940 World Series, the Sullivans became the first father and son to have played in the Fall Classic. Baseball dopesters frequently remarked that if Billy Sr. could hit like his son, and if Billy Jr. could field like his father, they would be “the best catcher in the history of the game.”

Following Mary’s death in 1930, Sullivan married Myrtle Nash in June 1933 and the couple enjoyed many years together. Sullivan died of a heart ailment on January 28, 1965, only eight days after the death of his Chicago batterymate Nick Altrock, and just four days shy of his 90th birthday. Survived by Myrtle, he was buried in St. James Catholic Cemetery in McMinnville, Oregon.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Baseball-reference.com.

Billy Sullivan’s clipping file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Brown, Warren. The Chicago White Sox. New York: Putnam, 1952.

Lindberg, Richard C. The White Sox Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1997.

Shatzkin, Mike, ed. The Ballplayers. New York: Arbor House, 1990.

Spalding’s Baseball Guide.

Spink, Alfred H. The National Game. 2nd ed. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2000.

Full Name

William Joseph Sullivan

Born

February 1, 1875 at Oakland, WI (USA)

Died

January 28, 1965 at Newberg, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.