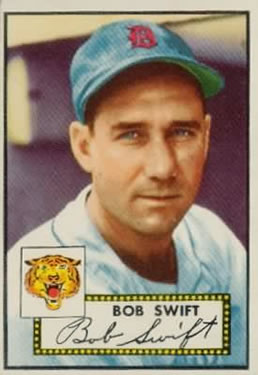

Bob Swift

In 1965 sportswriter Jerry Izenberg reflected, “When you think of the anatomy which kept Bob Swift active as a major league catcher for so many years, you look at the hands.” Not the legs, suggested Izenberg, because Swift wasn’t a fast runner, or the wrists, because he wasn’t known for his hitting.

In 1965 sportswriter Jerry Izenberg reflected, “When you think of the anatomy which kept Bob Swift active as a major league catcher for so many years, you look at the hands.” Not the legs, suggested Izenberg, because Swift wasn’t a fast runner, or the wrists, because he wasn’t known for his hitting.

“The hands kept him in the big leagues for 14 years,” Izenberg observed. “They are catcher’s hands and the top left knuckle on his left index finger defies all the laws of physics because one day a man named Mike Milosevich slid into it and bent it half way down the foul line.”1

Indeed, Swift never put up impressive batting statistics during his career in the major leagues. His average from 1940 through 1953 with the St Louis Browns, Philadelphia Athletics, and Detroit Tigers was just .231, with 14 home runs and 238 RBIs. But Swift was a superb defensive catcher, with a strong and accurate arm. As a handler of pitchers, perhaps the highest compliment came from Fred Hutchinson, who won 95 games for Detroit from 1939 to 1953. Hutchinson said, “I never shook him off once.”2

Swift also played a key role in one of baseball’s most comic moments: when he caught the four straight balls thrown to Eddie Gaedel, the 3-foot-7 batter St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck sent to the plate in 1951 for the express purpose of drawing a walk with his miniature strike zone.

Swift’s significant impact on the game continued as a big-league coach for 10 years over the period from 1953 through 1966. During this time, he was also a minor-league manager for two seasons plus part of a third. He treated everyone around him with respect. Though he never ran a club for a full season at the top level, he served three successful stints as an interim manager. The first, which was unofficial and thus not listed in Baseball-Reference.com, came with Kansas City in 1959. He later skippered the Tigers for parts of 1965 and 1966. Sad to relate, terminal cancer ended Swift’s career in May 1966. He died later that year, aged just 51.

***

Robert Virgil Swift was born on March 6, 1915, in the crossroads town of Kipp, Kansas, a few miles southeast of Salina in the east-central part of the state.3 His father was J.R. “Speedy” Swift, district manager for the Kansas City Power & Light Co. – so nicknamed because he pitched for semipro teams around Salina.4 His mother was Irene Therese Ford Swift, who died from blood poisoning just a year and a half after Bob was born. In 1919 Laura Musgrove Swift became his stepmother. He had a brother named Bruce and a sister, Margaret Roe.

Baseball caught on with Bob at an early age. He reportedly tended the bats for the Salina team “as a little tyke”at the old Western League field.5

He attended Salina High School and played football and basketball. The school didn’t have a baseball team, but in the summer Swift played for the Salina American Legion and Ban Johnson league teams. His prowess as a catcher was evident even then. In a farewell story in the Salina Journal after Swift’s death, sports editor Bill Burke remembered a time when Salina’s Legion program was just getting started.

“Dwight Catherman, owner of Catherman Construction Co., was a catcher in his younger days as a baseball player,” Burke wrote. “In the early 1930s, at the start of the Salina American Legion baseball program, it appeared he might have the catching job sewed up on the Salina team managed by Harry Suter.”

Burke then recalled the night two boys reported a week late for practice. “Harry asked in a gruff voice, ‘Well, what do you do?’

“‘I play ball,’ Bruce Swift fired back. Suter looked at his brother Bob. ‘Well, what do you do?’ Bob gave him the same answer. The Swift boys were catchers but Bruce switched to first base.”

While the conversation continued, Burke wrote, Catherman was having problems behind the plate, especially with his pegs to second. “Suter told Bob Swift to move behind the plate, and he did. He threw five perfect strikes to the keystone sack. ‘I never put on a catcher’s mitt after that,’ Dwight recalled. ‘I lost my job to Bob Swift, and I couldn’t have lost the job to a finer fellow.’”6

With Swift behind the plate, Salina went all the way to the American Legion national semifinals in 1930, only to lose to New Orleans.7

Dick Farrington offered a slightly different account of Swift’s route to catcher when he profiled Swift in The Sporting News in 1941. Farrington wrote that Bob played second base and his brother Bruce was the catcher on that Legion team, but Bruce broke his wrist and Bob put on the catcher’s gear at the urging of teammates.8

In 1934, at age 19, Swift left Salina to turn pro. Detroit Tigers scout Steve O’Rourke saw Swift at a Ban Johnson Kansas League championship game in 1933 and signed him.9

He first played for the Muskogee (Oklahoma) Tigers in the Class C Western Association. He had a successful season, batting .300 and recording a slugging percentage of .460 in 69 games.

In 1935 Swift played in 111 games for the Henderson (Texas) Oilers, a Tigers affiliate, batting .220. That year, he married Sarah Edith Hull. They had one daughter, Sue Ann.

In 1936 Swift played in the Tigers minor league system at Augusta, Georgia; Charleston, West Virgina; and Palatka, Florida. The next year he was acquired by the New York Yankees as part of a minor-league working agreement, playing again at Augusta and Palatka, which had become New York affiliates. In 1938 he was traded to the St, Louis Browns for cash and minor leaguer Stan Keyes, and was assigned to San Antonio of the Class A1 Texas League.

The 5-foot-11, 180-pound catcher continued to impress with his rifle arm and deadly accuracy. After Swift’s death, sportswriter Harold Scherwitz of the San Antonio Light remembered his throwing ability.

“A lot of San Antonio fans were saddened as they thought back to 1938 and 1939 when Swifty was a peppery youngster and crowds jammed the Tech seats. … In one of those seasons, the San Antonio club drew 225,000 paid admissions – and Swift with his great throwing arm was among the magnets.

“These were hustling, individualistic ball players,” Scherwitz wrote. “They played for keeps every step of the way and they weren’t afraid to gamble if it meant winning.

“One of the gambling plays that paid off handsomely was the pickoff. Unfortunately, no records were kept but graceful Buck Stanton at first base took innumerable bullet throws from Swift, who could fire the ball while apparently looking in another direction, and the crowds went wild at the number of runners thus picked off.”10

San Antonio was a St. Louis Browns farm club, and after a respectable batting average of .263 in 1939, Swift got the call to the majors. His arrival in St. Louis created a bit of a stir, illustrated by a Jim Berryman cartoon in The Sporting News. Several word balloons trumpeted Swift’s abilities and the caption read: “The St. Louis Browns came up with the rookie receiving sensation of the ’40 season when Bob Swift left San Antonio to go behind the plate for Fred Haney’s team.”11

In that same issue, writer Dick Farrington reported that The Sporting News had named Swift catcher on their freshman all-star team for 1940.12

Swift played in 130 games for the Browns in 1940 and hit .244. In his first game, he collected two hits off Detroit’s ace pitcher, Bobo Newsom, and knocked in two runs as the Browns won that season opener.

Swift got into only 63 games with the Browns in 1941, batting .259. As the US entered World War II in December 1941, Swift was not called to duty, and was ultimately classified 4F, possibly because of a recurring stomach disorder.13

In 1942 Swift was hitting just .197 when he was traded with Bob Harris on June 1 to the Philadelphia Athletics for Frankie Hayes. His average got up to .229 in 60 games with the A’s in 1942, but it slumped to .192 in 77 games with Connie Mack’s club in 1943. At the end of the season, he and teammate Don Heffner were shipped off to Detroit for Rip Radcliff.14

The Motor City was Swift’s home for most of the rest of his baseball career. He caught 80 games for the Tigers in 1944 and started 83 during Detroit’s run to the American League championship in 1945.15 He took a back seat to Paul Richards in the ’45 World Series against the Chicago Cubs, however, starting just Game Three, which the Tigers lost on a one-hitter by Claude Passeau. But Swift was in the game for the Tigers’ celebration after they won Game Seven, 9-3. A foul ball by Chicago’s Bill Nicholson had broken Richards’ index finger, forcing him to the bench. Swift took over and was behind the plate to take the final pitches from Detroit ace Hal Newhouser.16

Swift batted .233 in that victorious year and had an on-base percentage of .298 in 310 plate appearances. That was actually one of his lowest OBPs with Detroit; he reached base at respectable rates over .300 in seven of his 10 seasons there.

His real value to the club, however, was behind the plate.

Year in, year out, Swift was among the leaders in throwing out baserunners. In 1944 he nailed 60.8 percent of runners trying to steal, ranking second in the American League. He led all AL catchers that year in fielding with an average of .991. Over his career, he caught 44.4 percent of potential basestealers, and recorded a career fielding percentage of .985, committing just 64 errors in 4,142 chances over 14 seasons.

Bob Swift of the Detroit Tigers catches a pitch as St. Louis Browns pinch-hitter Eddie Gaedel stands at the plate on August 19, 1951. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

But for all his defensive kudos and his 1945 World Series ring, Swift is probably best known for that bizarre incident at St. Louis against the Browns on August 19, 1951. In a photo many baseball fans recall, Swift is on his knees behind Gaedel, the diminutive pinch-hitter. Swift’s advice to his pitcher Bob Cain – coincidentally also from Salina – was to keep the pitches low and when he went back to the plate he lay flat on his stomach to lower the target, but the umpire intervened and Swift knelt instead.17 Nonetheless, Gaedel walked on four pitches and was replaced by a pinch-runner once he reached first base.

Years later, when a fan pointed out to Swift that a lot of people remembered him for that photo, Swift responded, “I guess so. I suppose it’s some sort of history. After the game I told Veeck he blew it – he should have waited until the Browns loaded the bases.

“He just looked at me and said, ‘When did the Browns ever load the bases?’

“I couldn’t answer that one,” said Swift.18

Swift and Cain had worked together before that. In the early 1940s, the Cozy Inn – a popular Salina burger joint – opened a location near the local Army base to cater to the GIs. In the offseason, the two ballplayers worked there as fry cooks to earn extra money.19

In 1952 Swift got into just 28 games for Detroit as the third-string catcher, but one made headlines. On June 17 he stepped into the batter’s box against New York in the bottom of the 11th with the game tied and bases loaded. He’d failed to get a hit or an RBI all year, but he let an inside pitch from Yankee Jim McDonald hit him in the left elbow, and Don Lenhardt trotted in from third with the winning run. The Yankees “nearly tore the umpire apart”over the call, while Swift’s teammates chided him for the maneuver.20

Zany moments like these dotted Swift’s career. As a minor leaguer he entered Muskogee’s last game of the 1934 season needing to go 4-for-7 to hit .300. He ended up one hit short, but his pitcher, Walter Lacey – who had three hits of his own in the game – told the scorekeeper, “Hell, give him one of mine.”The scorekeeper did and the record books state that Swift hit .300 that year.21

As the 1952 season wound down, the Salina Journal’s Burke admired Swift’s affection for his hometown and his love of kids and called on the town’s citizens to do more to express their appreciation for the catcher’s achievements. Burke credited Swift with having done more than any other to publicize his hometown to professional baseball.

“He was the first native Salinan to get to the majors and the first native Salinan to play in the World Series,” Burke wrote. “One season Swift was selected by the Sporting News as the best defensive catcher in the majors. Many tales have been spun about Swift’s ability to throw, too numerous to mention. But they are all true. They tell of his uncanny ability to hit objects on second base and his brilliant receiving behind the plate despite his advanced age as major league players go.”

Burke went on to suggest the town should hold a large banquet in Swift’s honor. He also recalled a special moment Swift created for a group of Salina youngsters. The local Eagles Club had sponsored a trip to St. Louis for about 30 boys to see Swift’s Detroit team play the Browns. Swift came up to their hotel to visit them, and sometime after that, the boys’ team manager received 30 baseballs for the kids, signed by each of the Tigers, compliments of Swift.

“It goes without saying,” wrote Burke, “that a carload of gilt [sic] would not tempt the boys to part with those baseballs.”22

The next year, Swift’s major-league playing career came to an end. He’d been released by Detroit after the 1952 season, but that December, it was announced that he would rejoin the Tigers as bullpen coach on Fred Hutchinson’s staff in 1953.23 He was activated as a player in mid-September “for honorary purposes” and appeared in two games, the first being his 1,000th game in the majors.24 The other came on September 27, when he rapped a double and recorded an RBI. That made him 1-for-3 for the season, the only time he ever hit .300 in the majors. He was 38.

Swift was released again by the Tigers after the 1953 season, but his professional baseball career continued for another 13 years, and he made the most of it. In 1954 he returned as a coach under Hutchinson. Then, in 1955, after Hutchinson quit the Tigers, Swift returned to active playing duty, appearing in a total of 53 games for Oakland and Seattle in the Pacific Coast League. The latter club was managed by Hutchinson.

Swift got his first managerial assignment in 1956. He piloted the Albuquerque Dukes, a New York Giants affiliate in the Class A Western League, to a disappointing 59-81 season and a seventh-place finish. After that, he joined Kansas City as a coach for the 1957-59 seasons.

Swift’s time with the A’s gave him the opportunity to manage at the big-league level. When manager Harry Craft became ill early in the 1959 season, Swift was asked to take over. He did and won 13 of the next 15 games he managed for the A’s, including a 10-game winning streak. “He ran it very well even though the club was less than spectacular,” recounted Jerry Izenberg several years later (in the same Syracuse Post-Standard column that described the ex-catcher’s hands).25

Despite his record, Swift, Craft, and the entire coaching staff were fired by the A’s at the end of the season, after the team finished in seventh place at 66-88. “Guys like Swift get lost in the shuffle too often,” wrote Jerry Izenberg, who described him as like “one who is sick the day the foreman is fired or is too busy doing his job to be noticed by the new boss. … When the season ended they fired Craft and forgot about what Swift did,” the columnist wrote. “Nobody remembered 13 out of 15, so they fired him too.”26

In 1960 Swift coached for Washington, and in 1961 he came back to the Detroit organization. Tigers general manager Jim Campbell offered Swift the opportunity to return to the managerial ranks, but apologized that it was at Duluth, Minnesota, in the Northern League. “I’ll take it,” Swift said. “I’ve been that route before.”27

It was a good move. Swift’s team finished first with a record of 76-54, although it lost in the playoffs.

Swift was supposed to manage Nashville in the Southern Association in 1962, but when that league suspended operations, he spent the year as a scout instead.28 He also coached the Tigers’ entry in the Instructional League, working with manager Phil Cavarretta.29

In 1963 Swift was promoted to manage Detroit’s Triple-A International League club at Syracuse. He guided the Chiefs to a stellar start, going 36-24 before the Tigers called him up as a coach. He remained in that role for the rest of 1963 and all of 1964.

In 1965 Swift got his opportunity to manage again at the highest level. Tigers manager Charlie Dressen suffered a heart attack during spring training, and Swift became interim manager. He had the Tigers in third place, 24-18, just behind Chicago and Minnesota, when Dressen returned on May 31.

“Not bad for a guy who’ll now run the telephone to the bullpen,” wrote Joe Falls, sports columnist of the Detroit Free Press.30

But Swift was deferential and respectful, as usual. Asked if he’d miss managing the club, Swift said, “Yes I will. It’s been fun. But it’s still Charlie’s club.”31 Falls also reported that Swift didn’t want to return to the third-base coaching box when Dressen came back as manager. “If I sent a runner home and he was thrown out, some fans might think I did it to hurt Charlie’s chances,” Swift said. “I didn’t want this to happen because I think too much of Charlie.”32

Deep down, though, Swift wanted to guide a major-league team. “Now I feel I can do it,” he told Falls in an interview shortly after Dressen returned in 1965. “I think I’ve proved I can handle a major league club. The Kansas City thing was in mid-season. Harry Craft built that club so it wasn’t a fair test.” But he added that even though the Tigers were Dressen’s team, “I helped build it.”33

The next year, he got another chance. Dressen suffered another heart attack on May 16, 1966, and Swift was named interim manager again. With Dressen incapacitated, Swift’s Tigers went 32-25, not far off the pace, when Swift himself became ill. Hospitalized with what was thought to be food poisoning, Swift was later diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer. Longtime Tiger coach Frank Skaff took over the club in July.

Including his 13-2 stint with Kansas City, Swift’s managerial record in the majors was 69-45 (.605). The keys to his success were small-town simple: “There are two things a manager must know … how to handle his players and his pitching staff. Everything else is secondary,” he said.34

Swift died in Detroit on October 17, 1966.35 He was never an All-Star, nor was he a contender for Cooperstown. Yet he made an indelible impression on those who played with him and watched him play over his career in baseball. Joe Falls praised Swift’s accomplishments as a coach and interim manager in his column when Swift became ill, pointing out that Detroit players all appreciated Swift.

“You know why?” Falls wrote.

“Because Swift is a worker. He’s not an ‘executive coach’ doing little more than picking up stray bats in front of the dugout and hitting ground balls to the infield.

“He’s the field worker pitching practice almost every day, offering words of advice, words of encouragement, even on occasion biting words of baseball if this is what it took to wake up a player.

“Players respect him because he tries to help them, help them in the limited way a coach can help.

“Believe this or not, I never heard a player bum rap Bob Swift.”36

Of Swift’s managerial record, Falls wrote: “Bob never made it as a full-time manager. But maybe what he did … filling in three different times … running another man’s ball club while maintaining harmony on the team … and winning some games in the process … may have been an even greater accomplishment.”37

Swift was buried in Roselawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Salina. Whether or not Salina ever held the big banquet Burke had called for back in 1952, the city did honor his memory by naming the local Babe Ruth League organization after him. For years during the 1970s, the Bob Swift All Stars represented the city in youth baseball tournaments. (Another team was named for Bob Cain, fellow Salinan and Swift’s batterymate in that famous Eddie Gaedel at-bat.)38 In 1988 Swift was inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Detroit Free Press carried an editorial titled “Swift’s Vanishing Breed,” just a few days after Swift died. It depicted his ethos as follows:

“Baseball was a good deal more than a game for Bob Swift. He entered it when he was a Kansas country kid of 19 in the midst of a depression and didn’t leave until a fatal illness forced him out 32 years later.

“In these three decades, he formed a code for himself that was based on complete honesty and effort. He would tolerate or condone nothing less in himself or in any other player whom he coached or managed.

“This attitude was all a bit archaic to the new group of ballplayers, raised on fat bonuses and enthralled by their investment portfolios. There was a breach between the generations, one that Swift could never quite fathom.

“The Bob Swifts are the last of the tough, lean men who were totally dedicated to the game. And each time one of them passes on, it becomes less of a game.”39

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by members of the SABR BioProject factchecking team.,

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, retrosheet.org, Findagrave.com, and Ksbaseballhof.com.

Notes

1 Jerry Izenberg, “At Large,” Syracuse Post Standard, June 3, 1965: 62.

2 “Bob Swift, Catcher, Coach, and Tigers’ Acting Manager,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1966: 40.

3 Registrar’s Report dated 10-16-40, Salina Public Library (Lori Berezovsky, Librarian). Also St. Louis Browns roster, The Sporting News, March 6, 1941: 5.

4 Obituary, Salina (Kansas) Journal, July 16, 1963: 2.

5 Dick Farrington, “Browns Boast Budding Backstop Star in Bobby Swift,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1941: 5.

6 Bill Burke, “Shooting Sports with BB,” Salina Journal, October 20, 1966: 9.

7 Farrington, “Browns Boast Budding Backstop Star in Bobby Swift.”

8 Farrington, “Browns Boast Budding Backstop Star in Bobby Swift.”

9 Farrington, “Browns Boast Budding Backstop Star in Bobby Swift.”

10 Harold Scherwitz, “Sports Light, A Favorite Passes,” San Antonio Light, October 18, 1966: 13.

11 The Sporting News, March 6, 1941: 5.

12 Farrington, “Browns Boast Budding Backstop Star in Bobby Swift.”

13 “Today’s Sports in Short Order,” Detroit Free Press, December. 29, 1943: 10.

14 “First Post-Season Baseball Trade,” Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, October. 20, 1943: 9.

15 Golden Baseball Magazine, 1945 World Series (www.goldenrankings.com/ultimategame8.htm).

16 Golden Baseball Magazine, 1945 World Series (www.goldenrankings.com/ultimategame8.htm).

17 Bob Cain became a big part of Browns lore,” RetroSimba.com, February 5, 2022.

18 Izenberg, “At Large.”

19 www.Cozyburger.com/history.

20 “Tigers Blow Big Lead but Nip Yanks in 11th, 7-6,” Detroit Free Press, June 18, 1952: 14.

21 Izenberg, “At Large.”

22 Bill Burke, “Coming Out Swinging,” Salina Journal, September 28, 1952: 18.

23 “In the Valley of the Sun,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1952: 7.

24 Watson Spoelstra, “60 Victories Real Feather in Hutch’s Cap,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1953: 11.

25 Izenberg, “At Large.”

26 Izenberg, “At Large.”

27 Izenberg, “At Large.”

28 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1962: 36.

29 “Tiger Tales,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1962: 12.

30 Joe Falls, “Rock Comes Back to Haunt Tigers,” Detroit Free Press, May 31, 1965: 21.

31 Falls, “Rock Comes Back to Haunt Tigers.”

32 Joe Falls, “Bob Swift: Honest, Loyal in Every Way,” Detroit Free Press, October 18, 1966 :35.

33 Joe Falls, “Bob Swift Proved He Could Manage in Majors,” Detroit Free Press, July 23, 1966: 25.

34 Joe Falls, “Tigers in Good Hands,” Detroit Free Press, March 10, 1965: 27.

35 George Kantor, “Sports Quiz, Frank Skaff Always Aspired to Manage in the Majors,” Detroit Free Press, August 28, 1966: 34.

36 Falls, “Bob Swift Proved He Could Manage in Majors.”

37 Falls, “Bob Swift: Honest, Loyal in Every Way.”

38 “Bob Swift Stars to State Tourney,” Salina Journal, May 30, 1973: 17.

39 “Swift’s Vanishing Breed,”Detroit Free Press, October. 19, 1966: 6.

Full Name

Robert Virgil Swift

Born

March 6, 1915 at Kipp, KS (USA)

Died

October 17, 1966 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.