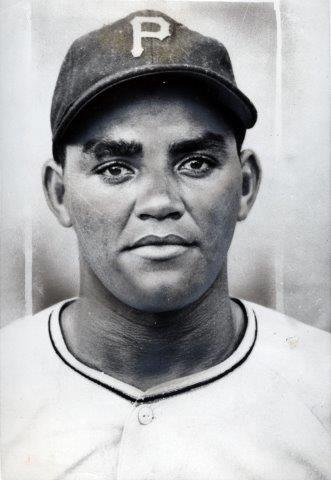

Carlos Bernier

He was a very good ballplayer. Certainly good enough that he posted some outstanding numbers during a long and distinguished minor-league career. Probably good enough that he could have had a substantial major-league life. But Carlos Bernier managed to play only one season in “The Show.” As Steve Treder wrote, “The baseball career of Carlos Bernier was in fact deeply intertwined with many of the most interesting and complicated issues of mid-20th century professional baseball: integration, racism, and the changing relationship between major league and minor league baseball in the 1950s and 1960s.”1 These factors, together with personality issues, combined to prevent the kind of career that his undeniable talent promised. He ended his life, tragically, at the age of 60, with his potential unfulfilled.

He was a very good ballplayer. Certainly good enough that he posted some outstanding numbers during a long and distinguished minor-league career. Probably good enough that he could have had a substantial major-league life. But Carlos Bernier managed to play only one season in “The Show.” As Steve Treder wrote, “The baseball career of Carlos Bernier was in fact deeply intertwined with many of the most interesting and complicated issues of mid-20th century professional baseball: integration, racism, and the changing relationship between major league and minor league baseball in the 1950s and 1960s.”1 These factors, together with personality issues, combined to prevent the kind of career that his undeniable talent promised. He ended his life, tragically, at the age of 60, with his potential unfulfilled.

Carlos Bernier Rodriguez was born in Juana Diaz, on the southern coast of Puerto Rico, a few miles east of Ponce. At the time of Bernier’s birth, the area produced rum from locally grown sugar cane. During Bernier’s childhood, however, the Puerto Rican sugar cane industry suffered a sharp decline. Juana Diaz became known as La Ciudad del Mabi, in honor of a fermented beverage made from the bark of the mabi tree.

Little is known of Carlos’s childhood. There is no record of his having played high-school baseball. He probably learned the game on the sandlots of his native area. Early in his professional career he played in the Manitoba-Dakota League. He claimed to be a teenager when his pro career started. Like so many players of his era, he lied about his age, thinking his chances of making it in the pros were greater if he appeared younger than his real age. He told baseball scouts that he was born in 1929, not 1927. As an independent circuit, the Mandak League was not recognized by Organized Baseball. Standard baseball references carry very little data on its teams or players.

The Sporting News did not cover the Mandak League. The first mention of Bernier in the self-proclaimed “Baseball Bible” came in a report of the 1948 Puerto Rico League championship series.2 With the score tied in the 10th inning of the seventh and deciding game, Mayaguez left fielder Bernier committed an error that led to his team’s defeat. Bernier played 19 years in Puerto Rico, mostly for Mayaguez in the winter league after spending the summers playing minor-league baseball in the United States

In 1948, 21-year-old Bernier got his start in Organized Baseball with the Port Chester (New York) Clippers in the Class-B Colonial League. Although the Clippers were affiliated with the St. Louis Browns, Bernier was the property of the local club rather than the parent organization.3 According to Joe Guzzardi, in 1948 Bernier was, along with Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, and Hank Thompson, one of Organized Baseball’s four black players.4 Evidently, Guzzardi overlooked Dan Bankhead and Roy Campanella, both of whom played in O.B. in 1948. (Willard Brown had played in the majors in 1947, but he was back in the Negro Leagues in 1948.)

Bernier did not have an outstanding season with Port Chester. A switch-hitter, he hit for neither average nor power, but he walked 54 times and stole 24 bases, enabling him to score 72 runs in only 104 games. Far more important than his statistics was an incident that occurred that season: He was struck by a pitch, which fractured his skull and caused him to suffer from chronic headaches the rest of his life.5 The headaches were sometimes blamed for the quick temper that kept him in hot water much of the time. It was not just headaches that got him in trouble. Jackie Robinson was able to endure the slurs and indignities that came with being a racial pioneer. Bernier was different. He was not one to take racial taunts lying down, whether from opponents, teammates, fans, or umpires. He was competitive and aggressive on the ballfield, and was suspended many times throughout his career.

Ron Samford, a longtime teammate of Bernier’s, both in Puerto Rico and the Pacific Coast League, was quoted as saying, “Bernier had the ability to be a ten-to-fifteen-year major league career. His temper got the best of him.”6 Sportswriter John Schulian wrote, “Carlos Bernier had a temper as big as his chaw of tobacco.”7

Bernier’s son, Dr. N. Bernier-Collazo, explained his father’s behavior:

He lived in an era when it was fashionable to discriminate; in fact, many states upheld laws that discriminated against people of color. My father’s only shortfall was that he did not handle the injustices of society with the same grace as a Jackie Robinson or a Roberto Clemente. He was quite angry at the injustices and faced them head on, even if it meant challenging a white minor league umpire who made a racial slur. I have often wondered how different life would have been for him with all his talents if he had played now (2004), instead of then. His career would have been spent primarily in the majors, rather than in the minors. … Despite his extremely competitive demeanor on the field, he was a gentle soul off the field with the greatest qualities; kindness, compassionate, generous, responsible, and loving. … Many people don’t know what a wonderful person he was because they only witnessed his exploits and his aggressive style of play on the field.8

During Bernier’s first season in the Colonial League, he drew his first suspension. League President John A. Scalzi meted out a six-day suspension and fined Bernier $25 for his part in a rhubarb with an umpire.9 Many more suspensions were to follow during Bernier’s career. Port Chester won the 1948 regular-season title in 1948 and followed up by taking the final playoff series. One highlight of the playoffs was an inside-the-park home run by Bernier at Poughkeepsie on September 19. He then returned to his native land to play for Mayaguez in the Puerto Rico League. He made his presence known, hitting two home runs in a game against Aguadilla on November 4. Mayaguez won the league championship, giving Bernier the distinction of having played for championship clubs in both the summer of 1948 and the winter of 1948-49.

After the 1948 season, the Port Chester Clippers disbanded, but Bernier remained in the Colonial League, the property of the Bristol (Connecticut) Owls. At the beginning of the 1949 season, the Owls sent him to Indianapolis of the Triple-A American Association. He didn’t stay in Indiana long. After two pinch-running appearances, the Indians returned him to Bristol. Bernier gave up on switch-hitting and infield play and became a full-time right-handed batter and outfielder. He had a terrific season, leading Bristol to the pennant, hitting .336, leading the league with 136 runs scored and setting a league record for stolen bases with 89. But not all was sweetness and light. On July 25 Bristol manager Al Barillari fined Bernier $50 for what he called “two stupid plays that cost us the game with Bridgeport.”10 According to the manager, Bernier missed a bunt sign in the previous night’s game and then was thrown out attempting to steal. In the winter Bernier again played for Mayaguez in the Puerto Rico League and tied the circuit’s record for stolen bases in one season with 33.

In 1950 Bernier was back with Bristol and got off to a great start. On May 4 he established a league record by stealing six bases in one game. He stole second base four times and third twice, but was foiled in his attempt for seven thefts when he was thrown out trying to steal home in the ninth inning of the game against Bridgeport.11 In 52 games for Bristol Bernier stole 53 bases and scored 67 runs. On July 14 the financially struggling Colonial League disbanded. Before the league collapsed, however, the Owls sold Bernier to St. Jean (Quebec) of the Class-C Provincial League. At the time of the sale, Bernier was leading the Colonial League in both stolen bases and home runs. He found the Canadian league to his liking. In 64 games for St. Jean he hit .335 with 15 home runs, scored 69 runs, and stole 41 bases, giving him a total of 94 steals for the two clubs.

In 1951 Bernier played for the independent Tampa Smokers in the Class-B Florida International League. He led the league in steals, triples, and runs scored. As frequently happened wherever he played, Bernier led his club to the pennant. His performance in Florida earned Bernier a big promotion. In 1952 he leaped all the way up to the top of the minor-league hierarchy with the Hollywood Stars of the Open Classification Pacific Coast League. Already known as “The Comet” for his speed on the basepaths, Bernier lit up the Southern California landscape. He hit .301 (third best in the league) and led the PCL in runs scored with 105 and stolen bases with 65. Once again he led his team to the league championship. He was named the PCL’s rookie of the year.

Pittsburgh promoted Bernier to the majors in 1953. He became the first black player to join the Pirates. (Some sources credit Curt Roberts with being Pittsburgh’s first black player, classifying Bernier as neither black nor white, but as Puerto Rican, as though Puerto Ricans were a separate race. Of course, biologically nobody really is black or white. Race is a sociological concept, not a biological one. Bernier considered himself black and deserves the distinction of being designated Pittsburgh’s first black player.)

Bernier made his major-league debut at Forbes Field on April 22, 1953, at the age of 26. He entered the game in the eighth inning as a pinch-hitter for pitcher Paul La Palme, with the Pirates trailing Jim Hearn and the New York Giants 4-0. In his first at-bat he was hit by a pitch, advanced to third base on two consecutive singles, and scored the Pirates’ first run of the game on an outfield lineout by Ralph Kiner. Bernier made his first major-league hit three days later at Connie Mack Stadium. In the seventh inning he hit a single off Curt Simmons in Pittsburgh’s 7-6 loss to the Phillies.

On May 2 Bernier made headlines in the sports pages by hitting three triples in one game, tying a major-league record that has been frequently tied but never broken. In the game against the Cincinnati Reds at Forbes Field, Bernier hit a triple off Bud Podbielan in the fourth inning, followed by triples off Herm Wehmeier in the sixth and seventh. His line for the game read 4-for-5, with three runs scored and three runs batted in. Of course, he couldn’t keep up that pace and slipped badly, losing his starting position later in the season. His final major-league appearance came at Ebbets Field on September 22, 1953. With the Pirates trailing the Brooklyn Dodgers 5-4 in the ninth inning, he entered the game as a pinch-hitter for Dick Smith. Brooklyn pitcher Clem Labine retired him on a grounder to shortstop. Bernier’s major-league career was over at the age of 26. He finished with a batting average of only .213. Although he stole 15 bases, he was caught stealing 14 times.

During the winter of 1953-54, The Sporting News asked baseball writers to rate players on various characteristics. The scribes named Carlos Bernier Pittsburgh’s most temperamental player.12 Events of 1954 served to strengthen that impression.

Bernier was on the Pirates’ spring-training roster in 1954, but was optioned conditionally to Hollywood shortly before Opening Day. He hadn’t been long on the Coast before his temper flared. On April 30 he “staged a stormy scene at San Francisco after being picked off second base and was banished by umpire Cece Carlucci.”13 A more serious incident occurred on June 13 in a game between the Stars and the Los Angeles Angels. While trying to steal second base, Bernier was tagged out by shortstop Bud Hardin, who claimed that Bernier deliberately kicked him in the shins. Bernier accused Hardin of tagging him with more force than necessary. Players from both clubs rushed to the aid of their teammates. With the help of police, the umpires restored order. However, when Bernier returned to the dugout he said something that caused the Angels first baseman to charge him. The melee threatened to escalate until cooler heads prevailed. Numerous fights broke out in the grandstand with participants being ejected. After hearing a report from the umpires, PCL President Pants Rowland fined Bernier $50 and suspended him indefinitely.14

In the first day after his suspension was lifted, Bernier stole three bases. He was back to his own fiery self again. On August 11 in the eighth inning of a game against San Diego, Bernier was called out on strikes by umpire Chris Valenti. Bernier’s temper flared. He bumped the umpire, who ordered him off the field. Bernier then slapped Valenti in the face with his left hand. The arbiter did not retaliate. Jack Phillips rushed over from the on-deck circle and restrained his angry teammate. After the game Bernier sought out Valenti, and with tears streaming down his face apologized for his actions. The two men shook hands.15

The next day Rowland suspended Bernier for the rest of the regular season and the playoffs. Hollywood president Rob Cobb expressed his disappointment over Bernier’s conduct: “I hope Bernier, whom all of us in the front office have repeatedly urged to control his temper, realizes the seriousness of the suspension and that he profits by his mistake. A player of his ability will be mighty hard to replace.”16

A few weeks later it was reported that Bernier had signed a contract to play with the Licey club in the Dominican Republic League, a circuit not affiliated with Organized Baseball. George M. Trautman, president of the National Association, the governing body of the minor leagues, reportedly wired Bernier that he would be placed on the disqualified list, barring him from winter league ball, unless he quit the Licey team immediately.17

Despite Trautman’s warning, Bernier played for Licey. He participated in all five games of the league playoffs. He was tossed out of Game Four after a dispute over a decision by the second-base umpire.18 Bernier appealed to Trautman to lift the ban so he might play ball in his native Puerto Rico this winter. He assured the president that he would behave himself and never again get into arguments with umpires.19 The ban was lifted. In a nonbaseball note, on October 2 Bernier remarried his ex-wife, Emma Betances.

Bernier played winter ball in Puerto Rico, went to spring training with the Pirates, and became a member of perhaps the first black, all-Caribbean outfield on a major-league club when he joined Román Mejías and Roberto Clemente in the Pittsburgh outer garden for a game against the Phillies at Clearwater on March 13, 1955.

Bernier was back in Hollywood for the opening of the 1955 season. In early June Carlos’s mother, 65-year-old Rosario Bernier, came to California from Puerto Rico for a visit with her son. It was her first trip to the United States mainland. Inexplicably, The Sporting News account of her visit focused on Ms. Bernier’s smoking habits rather than on any of the other aspects of her visit that would seem more pertinent.20 Carlos claimed to have turned over a new leaf. He said, “I learn my lesson. I’m a good boy now. I cause nobody no trouble no more.”21 He kept his promise during the 1955 PCL season and led the league in stolen bases. However, he got involved in fisticuffs in a game between Mayaguez and Caguas in Puerto Rico that winter. In a play at the plate Bernier was nearly hit in the head by a throw from Caguas first baseman Vic Power. Bernier claimed Power had deliberately thrown at him. The two got into a fist fight, which escalated into a brawl involving most players from both clubs, as well as many fans, who swarmed the field to join in the melee. Puerto Rico League President Ernesto Juan Fonfrias fined Bernier $100 for his part in the scuffle.22

The 1955 Puerto Rico League All-Star game was played in San Juan’s Estadio Sixto Escobar on December 12. Proceeds from the annual game go to a special fund to buy toys for the poor children of the island. A series of track and field events preceded the 1955 game. Not surprisingly, Carlos Bernier won the 100-meter dash.

Bernier continued to star in the Pacific Coast League for several years, but never made it back to the majors. Perhaps his reputation as a troublemaker deterred the big-league clubs from taking a chance on him. Bernier led the PCL in batting average in 1961, in on-base percentage in 1961 and 1963, in runs scored in 1958, in triples in 1956 and 1958, in walks in 1959 and 1963, in hits in 1958, and in stolen bases in 1955 and 1956. Some of these accomplishments occurred while he was playing for Hollywood, but most came after the club moved to Salt Lake City in 1958. He got off to the best start of his career that first season in Utah, hitting over .400 throughout the spring. He had a streak of hitting safely in 35 consecutive games in April and May. Bernier was selected to play in the Pacific Coast League All-Star game. After the season, the National Association of Baseball Writers named him to their all-Triple-A All-Star team.

Bernier’s numbers declined slightly in 1959, so he was demoted to the Columbus Jets, Pittsburgh’s affiliate in the Triple-A International League. After 35 games in Ohio he was acquired by the Indianapolis Indians, a Philadelphia Phillies affiliate in the same circuit. In May 1961 he was sold to Hawaii, and he was back in the Pacific Coast League. Bernier still couldn’t keep out of trouble. He was fined $100 for threatening and abusive language directed toward umpire Cece Carlucci in a game at Portland on July 3. Otherwise he had a terrific season. He won the PCL batting championship by hitting .351 for the Islanders, the highest batting average of his career. He was selected by National Association of Baseball Writers to the 1961 Class-AAA All-Star team. He followed this up with three more good seasons in the islands, hitting .313, .300, and .294 in 1962, 1963, and 1964, respectively.

In 1965 Bernier plied his trade south of the border, playing for the Reynosa Broncs in the Class-AA Mexican League. In his final season he hit .281 in 87games. He then retired at the age of 38, having played 17 years in the minors, one year in the majors, and probably 19 seasons of winter ball in his native Puerto Rico.

After Bernier retired, he was plagued by financial insecurity and medical and emotional problems.23 He was homeless near the end, and hanged himself in a garage in his hometown of Juana Diaz on April 6, 1989.

Carlos Bernier has not been forgotten. In 2004 he was inducted into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame. In 2012 the Orlando Cepeda Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research commemorated Bernier’s 85th anniversary with a celebration of his life at Los Autenticos Club in Juana Diaz. More than 130 people attended the event, which featured an exhibition of Bernier memorabilia and photos.24

This biography appeared in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Notes

1 Steve Treder, “Carlos Bernier,” hardballtimes.com/carlos/bernier, August 25, 2004.

2 Santiago Llorens, “Puerto Rican Playoffs Won by Caguas Club,” The Sporting News, March 17, 1948.

3 Treder.

4 Joe Guzzardi, “Carlos Bernier, More Than a Footnote,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 14, 2013.

5 “Obituaries: Carlos Bernier,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1989.

6 baseball-reference/bullpen/Carlos_Bernier.

7 Ibid.

8 Treder.

9 “First Colonial Suspension,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1948.

10 The Sporting News, August 10, 1949

11 The Sporting News, May 17, 1950.

12 C.C. Johnson Spink, “The Low Down on Majors’ Big Shots,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1954.

13 The Sporting News, May 12, 1954.

14 The Sporting News, June 23, 1954.

15 John B. Old, “Bernier Slaps Ump, Banned for Rest of ’64,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1954.

16 Ibid.

17 “Suspended Bernier Warned Not to Play in Dominican,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1954.

18 Albert Mlagon, “Bernier in New Ump Clash; Heaved in Dominican Game,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1954.

19 Santiago Llorens, “Bernier Asks Lift of Ban; Seeks to Play Winter Ball,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1954.

20 Jeane Hoffman, “Hollywood’s Fiery Bernier Had Cigar-Smoking Mamma,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1955.

21 “Bernier Back as Good Boy,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1955.

22 “Power, Bernier Fined $100 After Puerto Rican Scrap,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1955.

23 Guzzardi

24 Edwin Fernandez-Cruz, “SABR Day 2012 — Puerto Rico,” sabr.org/sabrday/2012/puertorico.

Full Name

Carlos Bernier Rodriguez

Born

January 28, 1927 at Juana Diaz, (P.R.)

Died

April 6, 1989 at Juana Diaz, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.