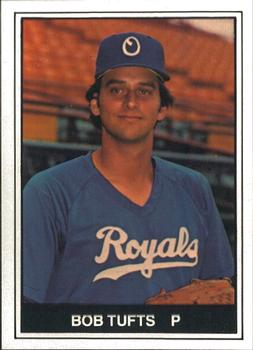

Bob Tufts

Bob Tufts was one of six big-leaguers known to have converted to Judaism during their careers.1 When it came time for Tufts to select his Hebrew name, something meaningful to him, he chose Sandy Koufax. His rabbi laughed but wasn’t impressed. He shook his head and asked Tufts to pick another name. Bob selected Reuven, from Reuven Malter in Chaim Potok’s 1967 bestselling novel, The Chosen.

Bob Tufts was one of six big-leaguers known to have converted to Judaism during their careers.1 When it came time for Tufts to select his Hebrew name, something meaningful to him, he chose Sandy Koufax. His rabbi laughed but wasn’t impressed. He shook his head and asked Tufts to pick another name. Bob selected Reuven, from Reuven Malter in Chaim Potok’s 1967 bestselling novel, The Chosen.

Tufts, a lefty who relieved in 27 games from 1981 through 1983, was also one of the uncommon Princeton University graduates to reach the majors. Indeed, for more than 40 years he was the only one.2 He met his future wife, Suzanne, there but not through baseball. “Nobody goes to baseball games in Princeton,” Tufts said.3

Robert Malcolm Tufts was born on November 2, 1955, in Medford, Massachusetts. His father, William Tufts Jr., was a bank vice president. His mother, Barbara Tufts, taught ninth grade. One of her first students in Medford was former major-league pitcher Bill Monbouquette. William and Barbara had two other children before Bob: daughter Sandy and son William III.

The two brothers played high-school baseball in Lynnfield, Massachusetts. Bill, three years Bob’s senior, was also a left-handed pitcher, good enough to receive a baseball scholarship to the University of Florida. After one year, he transferred to the University of New Hampshire, where he roomed with former big leaguer Rich Gale. Bill was an All-State pitcher in New Hampshire. He came to the attention of Cubs scout and former Cubs shortstop Lennie Merullo. In 1974 Bill played rookie ball for the Gulf Coast League Cubs. In 1975 he pitched for Key West, the Cubs’ Single-A affiliate in the Florida State League before calling it quits and becoming a schoolteacher, following in his mother’s footsteps.

Bob Tufts was a hard thrower in high school. “I threw conventionally as a high-school pitcher growing up in Lynnfield — four-seam fastballs, straight over the top and tried to throw hard with a curve that was a 12-to-6 type. I learned on my own to drop my arm angle and throw two-seam pitches in college and throw everything for the middle of the plate — and below the waist — to let the fastball sink and go away from righties (in to lefties) and to change the curve to a slider, dropping it down and in on them (and away from lefties). Over time, my motion became — well — an oddity and helped me become deceptive and a decent relief pitcher despite the lack of velocity.”4 Tufts utilized his height — 6-feet-5 when fully grown — to his advantage. “I was all elbows, throwing across my body, things flapping everywhere. People laughed at my motion.”5

After high school, Tufts attended and graduated from Princeton. He majored in economics and played baseball. Princeton wasn’t his first choice. “I wanted to go to Dartmouth. I really liked that part of New Hampshire.”6 But the Big Green rejected him. His high-school coach, Harry Vanieson, had connections with Walter “Pep” McCarthy, Princeton’s assistant athletic director. Tufts pitched two years for the collegiate Tigers. He was the team’s third starter in 1976 and went 5-3 with a 4.06 ERA. In his senior year Tufts was the ace of the staff, finishing with a 7-3 record in 11 starts. He notched six complete games and had a 2.64 ERA. “(Clarke Field) was a good pitcher’s park. Jadwin Gym, where the basketball team played, was located behind the outfield. It had a gray roof, and the sun would reflect off of it. I purposefully threw more overhand so that the ball would get lost in the roof. It provided a really bad background for the hitters.”7

It was at Princeton where Tufts interacted with a few Jewish students. He had been questioning his religious beliefs since the late 1960s and early 1970s. “I started questioning the idea that you can say or do everything bad as long as you say ‘Sorry’ at the end,” he said. “That’s not how one should live one’s life. One should basically be focused on the here and now, as opposed to promises thereafter.”8

Near the end of his senior year in college, he received calls from the Seattle Mariners, Cleveland Indians, and San Francisco Giants. Tufts acknowledged scout Lennie Merullo’s help. When the former Cubs shortstop signed older brother Bill Tufts, Lennie said to Bob, “I’ll make sure people know you are out there.”9 Merullo kept his word. The Giants drafted Bob in the 12th round (296th overall pick) of the 1977 draft. “I signed in the coffee shop of the New York Port Authority. No bonus. I got a cup of coffee, but I didn’t ask for a sandwich. I didn’t want to appear greedy,” Tufts said.10

He reported to the Pioneer (rookie) League in Great Falls, Montana. Bob pitched only 15 innings for the Great Falls Giants, compiling a 2-1 record before being promoted to the Cedar Rapids Giants in the Class A Midwest League. He pitched well there too. In nine games, he sported a 4-4 record with a 3.27 ERA.

In 1978 the Giants promoted Tufts to their Double-A team, the Waterbury (Connecticut) Giants in the Eastern League. Anxious to know how his son was doing, William Tufts regularly called the sports department of the Waterbury Republican-American. The first five times he called, he received the same response. “Bob pitched a complete-game victory last night.”11 William’s sixth call resulted in a different answer. “Your son pitched another complete game, a two-hitter, but lost, 1-0. Sorry.”12 In 21 games for Waterbury, Tufts compiled a 13-5 won-loss record with a 2.83 ERA. He started 19 games and completed 15 of them. Waterbury manager Andy Gilbert said of Tufts, “He knows how to pitch. Every pitch he throws has some movement on it. He’s a good competitor and he’s got the good attitude and desire to go with the stuff. He doesn’t beat himself.”13 During the last month and a half of the season, Tufts played for the Phoenix Giants in the Pacific Coast League. He pitched 48 innings and went 3-2 at the Triple-A level.

Tufts spent all of 1979 with the Shreveport Captains in the Double-A Texas League. Despite getting off to a slow start (he lost five of his first six decisions), he finished the year with a 14-10 record and a 2.45 ERA. However, he suffered his first arm injury during that season. “[It was] shoulder related. I was given indocin and butazolidin up to the limit and then had DMSO put on my shoulder,” he said, referring to a group of anti-inflammatories/painkillers. “[I] didn’t miss a start.”14 The slick-fielding All-Star pitcher was a minor-league Silver Glove award winner (60 chances, 45 assists, 15 putouts, no errors).

The 1980 season proved to be pivotal for Tufts. He was back with Phoenix, and Giants farm director Tom Haller decided to move him to the bullpen — an unwelcome surprise. Despite pitching effectively for Shreveport the prior year, Tufts found himself in unfamiliar territory. He received no help. “Had I remained a starter, I would have been better off,” he recalled. I had done well as a starter and was disappointed with the move to the bullpen. Routine is important. I was a sinker/slider pitcher. Because of the sudden change, I began to lose the feel of the ball. You have to throw enough, but not too much. Starting and relieving require completely different preparations. But I adjusted.”15 Tufts finished the season with a 6.52 ERA. He won 4 games, lost 7 and registered 3 saves.

His 1981 season began in Phoenix in the bullpen. Tufts pitched 69 innings and allowed 59 hits. He went 9-2 with a 1.70 ERA. It was quite a turnaround. “In 1980, after I was moved to the bullpen, I was the 10th man on a 10-man staff. As a sinker/slider pitcher, I needed regular work. In 1981 I felt less pressure and was more relaxed. The first week of the season, pitcher Al Hargesheimer took a line drive off his shin. I relieved and pitched 5⅓ innings. I was more aggressive, getting ahead on the count, and then expanding the strike zone. I just had more confidence.”16

In August of that strike-shortened season, San Francisco released Mike Sadek, Randy Moffitt, and Bill North. Bob Brenly, Jeff Leonard, and Tufts replaced the three. “The move surprised me,” Tufts recalled.17 His major-league debut came on August 10 in Candlestick Park against the Houston Astros. He relieved starter Doyle Alexander in the seventh inning with the Giants ahead, 3-1. The first batter he faced, Harry Spilman, pinch-hitting for Don Sutton, blooped a 1-and-2 slider into shallow left field for a single.18 Tufts gave up one unearned run in an inning’s work. He struck out one. The Giants ultimately lost the game 6-5.

On August 26, 1981, Tufts grounded out to short against the Cardinals’ Bob Sykes in his only big-league plate appearance. It was a game made infamous by Garry Templeton‘s obscene hand gesturing toward the crowd.19 In the first inning Templeton struck out against Gary Lavelle but the ball got away from catcher Milt May. Templeton didn’t run to first. “I looked into the Cardinals dugout at manager Whitey Herzog. He was fuming, It was also the game I struck out Keith Hernandez on a crappy slider,” recalled Tufts.20

In total that year for San Francisco, Tufts pitched 15⅓ innings in 11 appearances. He finished 0-0 with a 3.52 ERA.

On the next to last day of spring training 1982, March 30, the Giants traded former Cy Young Award winner Vida Blue and Tufts to the Kansas City Royals for Atlee Hammaker, Renie Martin, Craig Chamberlain, and Brad Wellman. Tufts hadn’t seen the move coming. “Tom Haller [by then Giants GM] had told me that I would be part of the 1982 team as a set-up man. I was slightly stunned, as I had been part of the organization since 1977 and knew nothing about the KC team except for Rich Gale, and Rich had already been traded to the Giants during that offseason.

“I flew to the Royals minor-league camp for the last week of spring training in 1982 and was greeted with a speech by minor-league director Dick Balderson, who talked about how getting married had ruined a prospect (I was … engaged [scheduled] to be married in November of 1982) and from other minor-league coaches that stressed how the major-league team needed hard throwers. (So why did they trade for me?) Ouch!”21

Tufts immediately noticed differences in Kansas City. “There was an expectation of winning in the Royals organization. Frank Robinson had just begun to try to put that stamp on the Giants team. And as demonstrated by the Royals Academy and an early acceptance of computers, the Royals were more open to new ideas and techniques.”22

Tufts began the 1982 season playing for Joe Sparks’ Omaha Royals in the American Association. But he was immediately called up to the big club — on April 6, Kansas City placed relief pitcher Scott Brown on the 21-day disabled list. Once Tufts joined the roster, he became the sixth southpaw on a staff of nine. (The others were Blue, Larry Gura, Paul Splittorff, Grant Jackson, and Bud Black.) Manager Dick Howser didn’t use Tufts. A week later, he was returned to Omaha. He pitched well in relief, sporting a 10-6 record with a 1.60 ERA to go along with 12 saves, stats good enough to earn “Fireman of the Year” and All-Star honors in the AA.

Pitching against the Wichita Aeros (then a Montreal Expos affiliate) on June 19, 1982, Tufts had the distinction of being both the losing and winning pitcher in a doubleheader. After 6½ hours of baseball, the finale didn’t end until 1:00 A.M. Tufts lost the opener when the Aeros scored four runs in the 10th inning, but he came back to win the late night (or early morning) nightcap. Afterward Aeros manager Felipe Alou asked him if he was crazy for pitching so many innings. “I just did what I was told,” recalled Tufts.23

After the American Association playoffs, Kansas City called up seven players including Tufts. He made his Royals debut on September 6, 1982, against the Mariners in Seattle. He pitched three innings, gave up five hits and one earned run, and struck out four. Bob’s first major-league victory came on September 12 in his next outing at Royals Stadium against the Minnesota Twins. Pitching the fifth and sixth innings, he allowed no runs. The losing pitcher for the Twins, Terry Felton, suffered the 16th and final defeat of his winless big-league career.24

Two days later against the Seattle Mariners, Tufts notched his first big-league save, going 3⅔ scoreless innings. It was the first time his parents had seen him pitch in a major-league game. Royals manager Dick Howser had this to say about Tufts, “He gets you the groundball and doesn’t walk many. And I like his makeup, he’s not afraid. Reports are good from both his Triple-A managers, Rocky Bridges and Joe Sparks. We’re not going to create opportunities for him, but I have the confidence to use him.”25 He finished the 1983 season with 10 appearances, two wins against no losses, and two saves.

Things looked bright for Tufts going into the 1983 season. In his “A.L. Beat” column in The Sporting News of February 7, 1983, Peter Gammons covered the Royals. He wrote, “The Royals were disappointed last year that neither Keith Creel nor Frank Wills stepped forward, but both are back for another try. Bob Tufts should make the club as a left-handed short man; He gets lefties out and has consistently won in the minors. He could be a big help for Dan Quisenberry.”26

In fact, Tufts made the Royals Opening Day roster. However, he didn’t pitch well that season, appearing in only six games. The Royals Review summed up Tufts’ final appearance. “[It] came on May 6, 1983, against Toronto, replacing Mike Armstrong in the bottom of the seventh with the Royals trailing 5-1 and runners on first and second. Tufts walked Ernie Whitt to load the bases, but got Willie Upshaw to pop out to end the inning.”27 He came out for the eighth, allowing two hits and one run.

Tufts never pitched in the major leagues again. The Royals sent him to Omaha soon after that outing. He’d lost velocity, and although he wasn’t in pain, Tufts later discovered he had a torn rotator cuff and had calcium deposits in his shoulder. In half a dozen outings, he’d given up 16 hits and 6 earned runs in 6⅔ innings. During three big-league seasons, he finished with a 2-0 record, 4.71 ERA and 2 saves. He struck out 28 and walked 14 in 42 innings.

Soon after sending Tufts to Omaha, the Royals, on June 7, traded him to Cincinnati for Charlie Leibrandt. Bob reported to the Indianapolis Indians in the American Association, the Reds’ Triple-A farm team. After the season he was granted free agency. One month shy of his 28th birthday, Bob Tufts was out of baseball.

Tufts said he thinks he could have played longer. “There’s always a need for left-handed relief pitchers, but I was blacklisted,” he said. “No one would sign me.”28 The reason stemmed from the 1983 cocaine scandal that engulfed several Royals players, including Vida Blue, Jerry Martin, Willie Wilson, and Willie Aikens. It was unreasonable and unjust, but because he had performed so poorly and shared the same clubhouse as the offenders, Tufts had a cloud of suspicion over his head. Yet a determined Tufts wouldn’t let the false accusations define him or hold him back.

After his baseball career, Tufts added another Ivy League school to his resume. He studied at Columbia University, earning an MBA in finance from its School of Business in 1986. A 1982 article in The Sporting News about Tufts begins, “One of Bob Tufts’ favorite time-killers is following the stock market.”29 The article was prophetic. After hanging up his spikes, Bob spent 22 years on Wall Street in futures and foreign exchange.

As of 2019 Tufts was a clinical assistant professor at the Sy Syms School of Business at Yeshiva University, teaching in the Business Strategy and Entrepreneurship Department. He was named the business school’s Teacher of the Year for the 2017-18 school year.30

It’s no surprise that Tufts turned to teaching, given his family history. Before his mother, his grandmother taught physics in the 1920s in New Haven, Connecticut, at a time when it was considered improper for women to teach physics. “My family is generations of teachers — we can go back to the 1820s,” Tufts recounted. 31

As of 2019 Bob and Suzanne Tufts lived in Queens, New York. They have one daughter, Abigail, herself an athlete. In 2009 Tufts was diagnosed with multiple myeloma (the same cancer that was fatal to Mel Stottlemyre and Don Baylor). He underwent treatment and had a successful stem-cell transplant. The cancer remained in remission for a decade, but resurfaced in February 2019. “The doctors have to be careful with me,” Tufts commented. “I only have one kidney.”32 Despite undergoing weekly treatments, he still took the subway from Queens into Manhattan to work. “I’ve only missed two days,” he proudly said.33

In addition to teaching and coaching pitching for the men’s baseball team at Yeshiva, Tufts was a fierce proponent of patient health care. “He advocates for medical access and choice in treatments on behalf of patients and doctors through My Life Is Worth It, an online not for profit he founded in 2013,” according to a health-care website. “He wrote healthcare columns for numerous outlets [including The Hill and Huffington Post], spoke at and attended major medical conventions and used social media to ensure that the patient voice and narrative is included in healthcare discussion.”34

Tufts said he had two messages. “First, we want patient and doctor access and choice in medicine — we want the right treatment at the right time for the right patient. All the restrictions that deal with these have to be justified, or they should be gone. Second, innovation is crucial, such as the proposal to use artificial intelligence to scan patient narratives to cut the time frame for drug development and reduce risk. With the right innovation, we will end up with cheaper drugs and more drugs, or we’ll end up with the same amount of cost to the system but better targeted care, which saves money in the long term.”35

When asked about his coolest memory and biggest challenge during his playing days, Tufts responded: “Pitching the first game was great, but I think my best memory was actually in Kansas City, where I got to hang around the legendary George Brett. He is one of the most genuine and outgoing people that I have ever met. As for my biggest challenge, it was sometimes difficult to keep the enjoyment of the game up, realizing that I am getting paid a lot of money to produce results. Baseball in a lot of ways mirrored a typical business job. I had a to do my work and continuously do it well, because if I didn’t, there was someone right behind me ready to take my place.”36

Tufts said he enjoyed watching New York Mets games, particularly listening to broadcasters Gary Cohen and (former Mets) Ron Darling and Keith Hernandez. “When someone does something wrong on the field, they point it out,” he said.37

Baseball ties run deep. At the 2008 Hall of Fame ceremony in Cooperstown, Tufts recalled that his old manager Frank Robinson was signing autographs (for a fee) behind a table on the street. Everyone referred to him as “Mr. Robinson.” Everyone, except Bob’s daughter, Abigail. She said, “My father used to play for Frank.” At which Robinson bellowed, “Who’s your father?” Calmly, Abigail responded, “Bob Tufts.” Robinson smiled. “Bob Tufts. Where is he? Tell him to come here and sit down with me. And his money is no good here.”38

Tufts’ Hebrew namesake, Reuven Malter, was used as a relief pitcher for his school’s varsity team. And like Tufts, Malter featured a decent sinker/slider. Malter said, “… I … developed a … pitch that would tempt a batter into a swing but would drop into a curve at the last moment and slide just below the flying bat for a strike.”39

Tufts was an Alfred Hitchcock movie buff. His favorites were The Third Man and The 39 Steps.40 He was also a professional ballplayer, scholar, Wall Street trader, health-care advocate, teacher, and fighter. Take your pick. Most importantly, he was a mensch.

Bob Tufts passed away on October 4, 2019. He was 63 years old.

Last revised: October 5, 2019

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank:

Bob Tufts for his time and information provided.

Rory Costello for his time and insightful edits.

This biography was also reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Baseball-almanac.com

Baseball-reference.com

Clubhouse Conversation, Then & Now Commentary on Royals Baseball from the Players Themselves (https://clubhouseconversation.com/2014/10/bob-tufts/)

Mark, Jonathan. “Now Pitching, ‘The Great Bob Tufts,’” The NY Jewish Week, May 3, 2011 (https://jewishweek.timesofisrael.com/now-pitching-the-great-bob-tufts/)

The Baseball Cube (https://thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=19039)

The Sporting News

Notes

1 The others are Elliott Maddox, Jeff Newman, Steve Yeager, Joel Horlen, and Skip Jutze. Bob Tufts, telephone interview with Bruce Harris, June 25, 2019 (hereafter Tufts interview #1).

2 Dave Sisler’s last year in the majors was 1962, and Chris Young did not arrive until 2004.

3 George Vecsey, “Sports of the Times; The Pitcher and the Lawyer.” New York Times, June 24, 1983.

4 Max Rieper, “An Interview with Former Royals Pitcher Bob Tufts,” Royals Review, July 16, 2012.

5 Bob Tufts, telephone interview with Bruce Harris, August 2, 2019 (hereafter Tufts interview #2).

6 Tufts interview #2.

7 Tufts interview #2. Clarke Field is named for catcher Bill “Boileryard” Clarke, who became an assistant coach at Princeton while still an active big leaguer. After retiring, he was the program’s head coach for many years. (https://goprincetontigers.com/facilities/?id=1).

8 Dan Epstein, “G-d Works in Mysterious Ways: Former Pitcher Bob Tufts on Lessons Learned from Conversion to Judaism and Baseball,” Jewish Baseball Museum, March 27, 2016.

9 Tufts interview #1.

10 Don Harrison, “Bob Tufts a Prize from Princeton,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1978: 41.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Bob Tufts, email to Bruce Harris, July 19, 2019.

15 Tufts interview #1.

16 Tufts interview #2.

17 Tufts interview #2.

18 Tufts, email to Bruce Harris, July 19, 2019.

19 Dan O’Neill, “Aug. 26, 1981: Garry Templeton’s Ladies Day Eruption,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 26, 2016 (https://stltoday.com/news/archives/aug-garry-templeton-s-ladies-day-eruption/article_e2ebeb70-ce60-592f-a506-99c938347842.html).

20 Tufts interview #2.

21 Rieper, “An Interview with Former Royals Pitcher Bob Tufts.”

22 Ibid.

23 Tufts interview #1.

24 Minnesota manager Billy Gardner put Felton in the game with the Twins up 7-4, with the express hope that Felton could get that elusive first win. Felton departed in the sixth still clinging to a 7-6 lead, but left two men on base. Both inherited runners scored and the Royals went on to win 18-7. Patrick Reusse, “Doubletakes,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1982: 47.

25 Mike McKenzie, “Stock Is Soaring for Rookie Tufts,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1982, 43.

26 Peter Gammons, “’83 Rookie Hurlers Need Introductions,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1983, 32.

27 Freneau [Will McDonald], “Happy Birthday Bob Tufts,” Royals Review, November 2, 2008.

28 Tufts interview #1.

29 McKenzie, “Stock Is Soaring for Rookie Tufts.”

30 Yeshiva University: yu.edu/faculty/pages/tufts-robert.

31 “A Whole New Ballgame,” Yeshiva University News, May 29, 2018.

32 Tufts interview #1.

33 Tufts interview #1.

34 Patients as Partners US Speakers: https://theconferenceforum.org/conferences/patients-as-partners/2019-speaking-faculty/bob-tufts/.

35 “A Whole New Ballgame.”

36 Gary Feder, “The Inside Scoop on YU’s Own Professor Robert Tufts,” The Commentator, April 18, 2016.

37 Tufts interview #1.

38 Tufts interview #1.

39 Chaim Potok, The Chosen (New York: Random House Publishing Group, First Ballantine Books Edition, December 1982), 6.

40 Tufts interview #2.

Full Name

Robert Malcolm Tufts

Born

November 2, 1955 at Medford, MA (USA)

Died

October 4, 2019 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.