Charlie Zink

Right-handed knuckleballer Charlie Zink put in his time, rising through the Boston Red Sox organization. He pitched for seven-plus years in the minors before finally getting the call to the big leagues. He was with the Boston team for only one day and got into just one game, but he did accomplish something that tens of thousands of others only dreamed of – he made the major leagues in baseball.

Right-handed knuckleballer Charlie Zink put in his time, rising through the Boston Red Sox organization. He pitched for seven-plus years in the minors before finally getting the call to the big leagues. He was with the Boston team for only one day and got into just one game, but he did accomplish something that tens of thousands of others only dreamed of – he made the major leagues in baseball.

Zink was hit hard in the one game he pitched – on a Thursday night at Fenway Park, August 12, 2008. He left after just 4 1/3 innings, having given up eight runs, but he didn’t bear a loss as the Red Sox won a 19-17 slugfest.

The rookie Zink started by retiring each of the three Texas Rangers he faced (all three of them All-Stars).1 The Boston offense then staked him to 10 runs in the first inning alone. Texas starter Scott Feldman was tagged for every one of those 10 runs (six of them came on a pair of three-runs homers by David Ortiz) and seemed headed for sure defeat. But neither pitcher figured in the final decision.

It had been almost a magical start for Zink. He held a 12-2 lead after four full innings. There was every reason to think he might pitch the requisite five innings and wind up with a win. But then he got hammered, departing after three consecutive doubles had helped bring the Rangers five runs. Two runners that reliever Javier López inherited both scored. The Rangers actually took the lead in the sixth, but in the end the Red Sox rallied and won.2

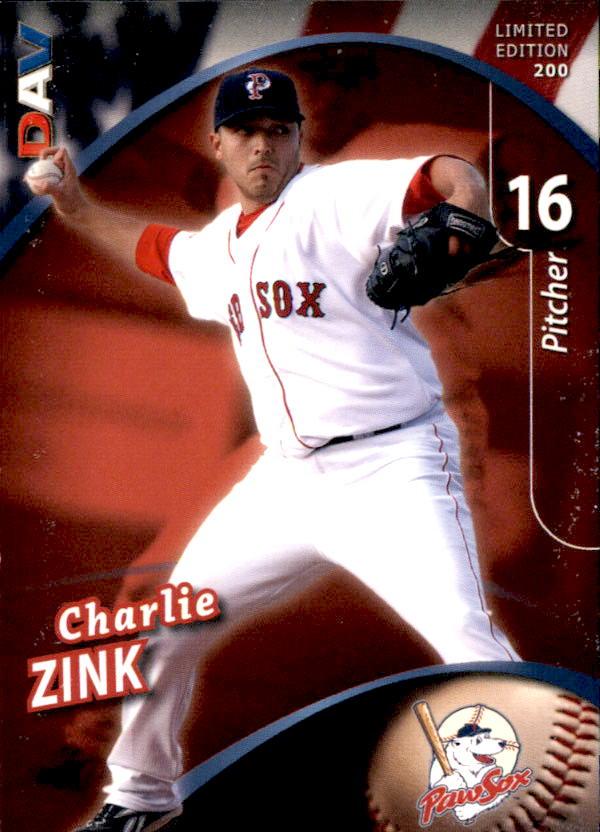

Zink had only been called up from Triple-A Pawtucket that very day. His contract was purchased after Tim Wakefield – a veteran knuckleballer himself – had to go on the 15-day disabled list.3 Zink had been 13-4 for the PawSox with a 2.69 ERA. Right after the game, Zink was optioned back to Pawtucket, with a 16.62 ERA. He had been with the big club less than 24 hours. After struggling with the PawSox in 2009, Zink pitched just three more games in the minors the following year. He wound up his pro career with a brief fling in independent ball in 2011.

Charles Tadao Zink was born on August 26, 1979, in Carmichael, California. He was the only child of Joyce and Ted Zink. Carmichael is a suburb of Sacramento, as is El Dorado Hills – about 20 miles farther east, where Charlie went to Oak Ridge High School.

His parents met in prison. Ted Zink was associate warden at Folsom State Prison, a “6-3, 260-pound man all the inmates called ‘Cobra.’” Joyce (née Ige) was a prison guard. She was Japanese-American by birth, and during World War II her parents had been held in one of the internment camps.4 Described as “tuned to injustice,” she began her career in 1971 at the California Institution for Women, then transferred to San Quentin the following year, and on to Folsom in 1973, where she was the first woman to supervise the visiting room. In time, she came to work “inside.”5 She retired as a captain from Folsom in 2000.

For his first year and a half, Charlie lived in Represa, “in a small house just outside of the prison, an environment his mom later described as ‘a gated community.’”6 The family then moved to El Dorado Hills, where Joyce Zink still lives as of 2025.

Charlie played some baseball as a child, but it wasn’t his first sport. “I didn’t start playing baseball until I was 11,” he recalled in 2007. “I had been in Taekwondo from the ages of 6-12, so that took up all my time. Then, one day my friend’s dad asked me to play on his Little League team, so I decided to give it a shot. I went to the tryouts and got drafted before he could pick me, so I wasn’t even on the same team as my friend. My dad and I would always throw a football, so I had a strong arm and pitching came very easy to me. In high school I played shortstop, first base, and pitched. I put up pretty good numbers my senior year… I think I hit .480 with 10 home runs and was 10-1 with a 1.00 ERA. I also threw a perfect game with a bunch of scouts there to watch me, but I didn’t throw hard enough to impress anyone.”7

Zink had played one summer – after his freshman year of high school – in a men’s adult league for a team called the El Dorado Generals, and then American Legion ball for the next three summers.8 His perfect game was for Oak Ridge High against Folsom High School in spring 1997.9 He also threw a couple of no-hitters in high school. He was runner-up for state Player of the Year as a senior but had no offers of athletic scholarships.10

After graduation in 1997, Zink went for a year to Sacramento City College, a community college. The team won the junior college national championship in 1998.11 Again, no scout approached with an offer, but he did catch someone else’s eye. None other than Luis Tiant recruited Zink to come to Georgia and pitch for the Savannah College of Art and Design. As head baseball coach at SCAD, Tiant went on a “scouting trip” to California and saw Charlie pitch for Sacramento. Tiant told a New York Times writer that he “saw Zink as a pitcher with a solid changeup and enough heat to be useful to his Division III program. . . So he transferred there for his sophomore year.”12 Zink received a full-ride scholarship to SCAD.13

In his first year with his new team, Zink had a notable impact. The Savannah Sun wrote on April 8 that he “mowed down Savannah State’s murderous lineup of hitters. The Tigers averaged better than 13 runs a game heading into the game. Zink allowed only four hits in a 3-1 Bees’ victory.”14 The Boston Globe added, “Tiant’s team is erratic but dangerous: After struggling all year, the Bees recently ended Savannah State University’s 46-game winning streak, the longest in collegiate history. The winning pitcher was Charlie Zink, a transfer student who turns his back to hitters in Tiantlike fashion.”15 But his overall stats weren’t spectacular: a “9-17 record, an ERA of almost 4.”16

At SCAD, Zink studied architecture and historic preservation. He recalled becoming interested in architecture because, in a sense, it was more tangible. “I realized I’m not artistic. I could draw you an apple, but I can’t paint an emotion.”17 He summed up his collegiate career in 2007 as follows. “I didn’t pitch a whole lot my freshman year, but we did win the state championship and I got a nice ring. Then I went to Savannah College of Art and Design with Luis Tiant as my head coach. I finished in the top five in the nation for K/9 my last two years there. At this point, the scouts said I threw hard enough, but they didn’t like my mechanics, so I ended up not getting drafted and wanted to give up on baseball. But I ended up getting the call to try out for the Red Sox and I’m still having fun playing baseball.”18

No team drafted Zink. “I went to college there because it was totally paid for, and I figured if I was good enough the scouts would find me no matter where I was,” Zink said. “That wasn’t the case playing in Division III in Georgia.”19 As Mark McDermott of the Sacramento Bee wrote, “He threw hard, but scouts saw something in his delivery that scared them off. Tryouts with the Seattle Mariners and Tampa Bay Devil Rays failed to produce a phone call.”

“I was throwing hard, and the scouts all said I was going to throw my arm out,” Zink said. “I didn’t understand, because the big knock on me before I was throwing 90 was I couldn’t throw hard. So after my senior year, I just gave up on baseball.” Indeed, he thought about trying to become a pro golfer. McDermott continued: “But the itch remained, and he played in the men’s adult baseball league in Sacramento, where he caught the eye of Leon Lee (Grant High), who was the Pacific Rim coordinator for the Chicago Cubs. Lee was interested in signing Zink but suggested he play some independent ball first.”20

In fall 2001, Zink entered professional pitching with the Yuma (Arizona) Bulldogs of the independent Western League. The 6-foot-1 righty, listed at 190 pounds, appeared in four games for a total of five innings, without a decision and with a 5.40 earned run average. The Cubs did not follow up, nor did any other offers ensue. He had, though, spent three years pitching for Tiant in Savannah, and when the Red Sox hired Tiant at the end of 2001, Zink had an in. He told Chaim Bloom, then writing for Baseball Prospectus, “I would have never gotten picked up if I hadn’t known Luis. I tried out for a few other teams – Blue Jays, Braves, Rangers – and they didn’t like me. The Red Sox only gave me a shot because Tiant told them to.”21

During spring training 2002, the Sox were reportedly “looking to sign a few ‘organizational players’ to fill out roster spots in the low minors.” Tiant asked Zink if he would come to Florida for a tryout. On April Fool’s Day 2002, Red Sox scout Dave Jauss signed him to his first professional contract.22 An undrafted free agent, his contract was without a bonus and only for the minor-league minimum of the day – $850 per month, and just for the few months of the season.23

Zink entered Boston’s minor-league ranks, working in 26 games that year – all in relief – for the Single-A Augusta GreenJackets (South Atlantic League). After 48 1/3 innings, he had an earned run average of 1.68. His father died of cancer that summer, the day after Father’s Day.24 Charlie Zink also worked in four games for the Florida State League’s Sarasota Red Sox. He threw nine innings, giving up just one unearned run.

Most of Zink’s 2003 season was spent at Sarasota again, this time starting 19 of the 24 games in which he worked. This was the year he began to work on a knuckleball, initially under the tutelage of Tim Wakefield and then during extended spring training at the suggestion of minor-league pitching coordinator “Goose” Gregson.25

Watching television, Zink had seen Wakefield pitch a decade earlier. “I actually figured out how to throw the knuckleball when I was 11, I think. I saw Wakefield throwing it during the [1992] playoffs for the Pirates and I was just fascinated. It came really easy to me and I would always throw it playing catch, However, I didn’t throw a knuckleball in a game until 2002. All of my coaches growing up said it was stupid, and I shouldn’t mess around with it.”26

The first time he threw it on a professional field was in the outfield at Augusta. Gregson happened to be there and saw Zink “idly playing catch…with the team’s strength and conditioning coach, Darren Wheeler…The ball shattered Wheeler’s Oakley sunglasses. Zink ran over in horror, and reacted with three words: ‘Dude, you’re bleeding.’”27 Wheeler had to go to the hospital and get five stitches.28 As Zink told Chaim Bloom, “They saw me hit a guy in the face and then hit our other players in the chest two or three times.”29

Wakefield said, “It’s kind of neat to mentor somebody and try to keep the art going.” He added, “It’s just a matter of doing it consistently enough. He just needs to get used to throwing it in a game and knowing how to get it over the plate and knowing how to make it move a little more. The more he does it, the better he’s going to be.”30 Zink began to enjoy himself. “I had a lot of guys laugh when they swing. They just swing right through the ball. I can’t help but laugh out there sometimes.”31

Zink’s record with Sarasota in 136 innings was 7-9 (3.90). In six starts with the Eastern League’s Double-A Portland Sea Dogs, he was 3-2 (3.43), with a pair of near no-hitters, taking one into the eighth and the other into the ninth. After the season, he was named Sarasota’s Minor League Pitcher of the Year.32

Zink had a rough year with Portland in 2004: 1-8 (5.79) in 18 starts. He’d simply lost his feel for the knuckler.33 He was also said to have “developed a cocksure attitude, a casual work ethic and eventually tendinitis in his right shoulder.”34 He struck out 50 batters but walked 72. He was sent to Sarasota in July, where he had another three starts; he was 0-2 with a nearly identical 5.65 ERA before his sore shoulder ended his season.

Zink ascribed a turnaround in approach in 2005 to watching Tim Wakefield’s workout regimen. “He was a beast,” recalled Zink. “He was doing everything, including a lot of weights. I was like ‘Oh, wow! This guy’s almost 40 years old and is in great shape, and this is probably what I need to do.”35 He explained, “Once I converted to being a knuckleball pitcher all the players said ‘You’re a knuckleball pitcher so you don’t need to work out,’… (because) I’m only throwing 65. I just bought into it because I had so much success my first year…I didn’t work out at all. That’s when I had my worst year ever (2004) because I didn’t lift at all and gave my arm some rest. It really had a negative effect on me.”36

It wasn’t that he was flirting with bad habits, but his upbringing likely helped him get back on track as well. From an early age, he was told tales of Folsom inmates such as Charles Manson and the Menendez brothers. His parents brought home photographs and confiscated items such as makeshift knives, and took him inside on occasion. “It was pretty scary stuff…I kept a pretty straight line growing up.”37

It took a while to turn things around; Zink’s 2005 season was also a difficult one, though the Red Sox stuck with him. “The path of the knuckleballer,” observed director of player development Ben Cherington, “is rarely linear.”38 Back with Portland, Zink’s won/lost record was better – 8-5 (4.87), as was his strikeout-to-walk ratio of 1.32. He threw his first career shutout in August.

In September, Zink got his first opportunity to pitch in Triple A, called up to Pawtucket. He was 2-1 in four games but with an ERA of 10.45. He then got a bit of extra work in the Arizona Fall League.

During 2005, the Red Sox drafted James “J.T.” Zink (born 1985), also a right-hander, with their 11th pick. J.T. pitched in the low minors for three years (2005-07), but never rose above Single A. Despite some media reports at the time, the two were not related. “Same name, in the same organization,” Charlie Zink said in 2024. “It showed up in a bunch of articles that my brother got drafted. I don’t have a brother, I’m an only child.”39

Charlie Zink started at Pawtucket in 2006, had a couple of “shaky starts,”40 and was sent to Portland. There he quickly recovered (two games in which he was 1-0); he then returned to Pawtucket on May 31 and spent the rest of the season in Triple A. He was 9-4 (4.03) with the PawSox in 23 games, 15 of them starts. Keeping himself in shape had helped him become more consistent in his work.41

His 2007 season was again spent more in Portland than Pawtucket. He began the season with the Sea Dogs and was 9-3 in 16 games with a 3.98 ERA, and 2-3 (5.89) in eight games for Pawtucket. The 11 wins ranked him third among Red Sox minor-leaguers.

In 2008, economics were different. In his seventh year, Zink was now up to $2,700 per month – for the months of the season. He was one of 166 players in the Red Sox minor-league system and – given his surname – last on the list (see page 597 of the 2008 Boston Red Sox Media Guide).

Early in 2008, he met his wife-to-be, Madeline Monroe, at the Providence restaurant where she worked as an event planner. “We were just introduced by a mutual friend. And she hated me, because I was a baseball player. It all worked out perfectly.”42

In his fourth season for Pawtucket, Zink pitched the best ball of his career. However, Tim Wakefield remained a key member of the Boston staff (he had World Series championship rings from 2004 and 2007 as a veteran of the Red Sox since 1995) – and no team was likely to carry two knuckleballers. That June, Zink had said, “It’s frustrating to know that because of what I do, I can only replace one guy up there. And he’s doing pretty well.”43

A couple of months later, though, Zink’s inspiration and mentor went on the DL with tightness in his pitching shoulder. Zink was called up for his brief stint in Boston. Getting his first start at the age of nearly 29, he became “the oldest American League starting pitcher in 10 years to make his major league debut.”44

The Red Sox were four games out of first place at the time. The Rangers were second in the AL West, 61-58. Zink had gotten the word just the day before. His mother knew he was being called up before he did – impressively, the Red Sox had clued Joyce in so that she could arrange to come from California to see her son’s debut.

As for Zink himself, when he arrived, “I didn’t really know how to get to the field, where I was supposed to go. I took a cab over to Fenway and the cab driver asked me where I needed to go, and I didn’t know. Wherever players go, I don’t know. So he dropped me off at the ticket office. I literally stood in line with fans buying tickets for the game. I had to wait. When I got to the window, I remember asking the lady, ‘Hey, I’m pitching today. Where do I go?’”

After he got suited up, “I remember playing catch, warming up, and being so scared I’d hit a fan. The wall’s so low. Backing my catcher up a little off the foul line. I had too much adrenaline. I didn’t want to airmail it and hit someone in the face. I always put my stuff at the end of the bench in the dugout and remember feeling a huge TV camera right next to my face – which you don’t experience in the minor leagues. I remember those things – but the game? I don’t really remember pitching much.”

Given that the Red Sox sent 13 batters to the plate, there was a long wait before the start of the second inning. “I remember waiting 40 minutes in between pitching. Asking someone to play catch with me. I was in the batting cage underneath, just throwing balls against the net to stay loose. I was just, ‘I don’t know what to do. I might get cold.’ I remember that, and then afterwards, it was just a relief to be…done.”

Zink ascribed the unfortunate way the game got away from him to not sticking with the knuckler: “My secondary pitches are not major-league-quality pitches… I needed to be smarter and stick with my knuckleball, which is the pitch that got me there (to Fenway).”45 He summed it up: “This will be the best memory of my life, still. Hopefully, there’s more to come, but if there’s not, this was still amazing tonight.”46

Back with Pawtucket, he won another game, while losing two. He finished the season with a 2.84 ERA. Zink was named the International League’s 2008 pitcher of the year.47 Zink put in another full year with the Red Sox organization in 2009. His contract had been assigned outright to Pawtucket, where he worked the full year. Zink started well enough but then tailed off badly. He hit a team-record 30 opposing batters and walked a career-high 93, striking out just 47. He started 23 games and relieved in four others, ending with a record of 6-15 (5.59) for a team that finished 61-82. In his last 10 starts he was 1-8 (8.10).48

A free agent at the end of the year, Zink signed with the St. Louis Cardinals but was released in late March. In late April, he signed with the Minnesota Twins and appeared in his last three games in Organized Baseball. He was 0-2 (12.75) for the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. Giving it one final shot in 2011, Zink made eight starts for the Lancaster Barnstormers in the independent Atlantic League. He was 2-2 (7.80).

Zink was ready to move on from baseball. He and Madeline had their first child that year, son Noah. “I just lost the passion for baseball. I had done everything I was told I couldn’t do. I was told I couldn’t play at the junior college level. I was told I wasn’t good enough to play in college. I was told I wasn’t good enough to play professionally. Told I wasn’t good enough to make it to the big leagues. “It was like, ‘Alright, I’m done.’ I didn’t have a passion for it anymore. It wasn’t just a game. When my son was born, I was tired of traveling around. I wanted to start a real life. “That took some finding out, figuring out what real life was.”

It was time to settle down. He began to work in automotive sales, first as the internet sales manager for Sacramento-based Von Housen Automotive Group. “It’s right for me. I’m not gone for 10 days at a time. I’m there every night.”49

In 2016, Zink moved over to Niello Mini, also of Sacramento, becoming their finance manager, sales manager, and general manager. The couple bought a small farm in the town of Auburn, California. As of September 2024, they had four children – Noah (13), Scarlett (11), Abigail (4), and Theodore (6 months).

In February 2024, he served briefly as general manager for Fairfield Automotive Partners, but not long afterward found a position he truly enjoys: general manager of a Subaru dealership for Lithia Motors, Inc., a large publicly traded dealership group. “It’s probably the happiest I’ve ever been,” he said in the 2024 interview.

Was Charlie Zink perhaps related to Walter Zink? The only other Zink to play major-league baseball to date was also a righty pitcher, appearing in two games for the New York Giants in July 1921.50

Will another Charlie Zink come to pitch for the Red Sox? Just as there had been some confusion in 2005, when Boston drafted J.T. Zink, it happened again almost 20 years later. In late 2023, the team signed a 6-foot-5, 18-year-old right-hander from Curaçao named Charlie Zink, to a $70,000 bonus. This Zink already had a 95-mph fastball and there were hopes he could throw even harder.51 “It caused quite a stir,” the original Charlie Zink said. “I started getting all these calls from my old buddies – like Manny Delcarmen. ‘You just signed back with the Red Sox?’” No, he assured them, at age 44. “I’m not doing anything athletic these days. The most I’m doing is coaching my kids’ Little League teams.”52

Last revised: January 28, 2025

Sources and acknowledgments

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheeet.org, and a number of other publications. Thanks to Charlie Zink for the September 2024 interview.

A video of Zink’s game is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PkdFMTi4QBo

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bill Lamb and fact-checked by Mark Sternman.

Photo credit: Charlie Zink, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Those first three batters were Ian Kinsler, Michael Young, and Josh Hamilton.

2 The 36 runs scored tied the American League record for the most tuns scored in any game. In a National League game on August 25, 1922, the Chicago Cubs beat the Philadelphia Phillies, 26-23. For the full story of this 2008 game, see the account by Jason Scheller on SABR’s Games Project. Zink had started for the PawSox on Friday, August 8.

3 Joshua Robinson, “A Knuckleballer is Waiting to Rise,” New York Times, June 17, 2008: D4.

4 Charlie Zink did not know his maternal grandparents. They had passed away when Joyce Zink was young, leaving her, two brothers, and a sister.

5 Don Chaddock, “First female Corrections Officers opened doors,” California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, March 17, 2015. https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/insidecdcr/2015/03/17/first-female-correctional-officers-opened-career-doors-in-california-prisons/.

6 Marty Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all,” WEEI.com, August 11, 2018. https://www.audacy.com/weei/blogs/10-years-later-reflecting-on-maybe-the-craziest-red-sox-game-of-all-time

7 “Twelve Questions with Charlie Zink,” SoxProspects.com, April 30, 2007. http://news.soxprospects.com/2007/04/twelve-questions-with-charlie-zink.html.

8 The Generals were owned by his Little League coach, who owned a company named General Pool and Spa Supply and gave Charlie his first job – “emptying all the chlorine out of the big trucks when they arrived. Emptying out garbage. He gave me the worst jobs, because he didn’t want me to enjoy working like that. He wanted me to work hard at baseball.”

9 In the 2024 interview, Zink noted that Folsom was their biggest competition at the time. Though a very good team then, Folsom has gone on to become a real powerhouse, one of the top teams in the country for pro football prospects.

10 Burt Wilson, “Zink Never Listened to the Naysayers,” Intelligencer Journal / Lancaster New Era (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), May 25, 2011: C1.

11 Wilson.

12 Robinson.

13 Mark McDermott, “The Pro Report,” Sacramento Bee, presented by McClatchy-Tribune Business News, July 8, 2007: 1.

14 Adam Van Brimmer, “Zink Enjoys Place in SSU-SCAD History,” Savannah Sun, April 8, 2001: 5B.

15 Steve Fainaru, “A Throwback: One of the First Defectors, Tiant, Still Pitching in for Game,” Boston Globe, May 29, 2000: E6. He became the Bees’ all-time strikeout leader. Marty Dobrow, “Imperfect pitch,” Boston Globe Magazine, May 4, 2008: 40.

16 Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all.”

17 September 2024 interview.

18 “Twelve Questions with Charlie Zink.”

19 McDermott.

20 McDermott.

21 Chaim Bloom, “Prospectus Q&A: Charlie Zink,” BaseballProspectus.com. May 26, 2004. https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/2907/prospectus-qa-charlie-zink/

22 Charlie Zink’s player questionnaire completed for William Weiss.

23 Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all.”

24 Charlie was able to rush back to California. “I got home to talk to him, and later that night he passed away. It seemed like he was just waiting for me to come home and talk, so we could say our goodbyes.” Bob Hohler, “Seconding the motion,” Boston Globe, March 3, 2004: F5.

25 David Heuschkel, “Sox Growing a Knuckler on the Farm,” Hartford Courant, April 10, 2003; C5.

26 “Twelve Questions with Charlie Zink.” He was in fact age 13 during the 1992 playoffs.

27 Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all.”

28 Fred Bierman, “A Knuckleballer Finds His Pitch,” New York Times, May 28, 2004: D7.

29 He added, “I’m sure they really liked that. Now, I had average stuff: I threw 90, had a good curve, good changeup…nothing stood out, but I hit spots, and I got people out. But there’s obviously a little more value to me if I can throw a knuckleball for strikes and get people out.” Bloom.

30 Bob Hohler, “Zink Gets Grip on Knuckler,” Boston Globe, August 10, 2003: C7.

31 Doug Fernandes, “No spin zone,” Venice Herald-Tribune (Sarasota, Florida), July 1, 2003: 1C.

32 2007 Boston Red Sox Media Guide, 590.

33 “Feel” was a major factor. As he told Marty Dobrow the following year, “Those are the days when I don’t have a clue,” he said. “Like I don’t even want to be a knuckleballer anymore. Honestly, I don’t know how I got it to move before.” Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all.”

34 Robinson. Zink was quoted as saying, “It was good for me to fail. I had so much success, I didn’t think I had to do anything. I was immature. I was going out all the time. I figured I could just throw up a knuckleball, and no one would be able to hit it.”

35 Mike Edelman, “Zink’s Story,” Firebrand of the American League, July 13, 2008. https://firebrandal.com/2008/07/13/zinks-story/

36 Edelman.

37 Hohler, “Seconding the motion.”

38 Dobrow, “Imperfect pitch.”

39 Author interview with Charlie Zink, September 25, 2024. J.T. Zink – from the State of Washington – pitched for three seasons in Boston’s minor-league system, never rising above Single-A ball. He ended his pro career with a partial season for the Colorado Rockies. Four years later, he pitched in nine games for the McAllen, Texas team in independent league baseball. He later became a baseball scout, most recently working for the Los Angeles Angels.

40 Jay N. Miller, “PawSox Notebook,” (Quincy, Massachusetts) Patriot Ledger, August 9, 2006: 24.

41 Nick Cafardo, “Zink refused to knuckle under,” Boston Globe, August 18, 2006; C5.

42 September 2024 interview.

43 Robinson.

44 Nathan Dominitz, “It’s Easy to See: Sullivan vs. Gnats,” Savannah Morning News, August 20, 2008: D1.

45 David Pevear, “Knuckling Under,” Sun (Lowell, Massachusetts), September 7, 2008.

46Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all.”

47 Pevear.

48 Adam Kilgore, “Kelly proving adept at ‘double play’,” Boston Globe, August 21, 2009: C3.

49 Dobrow, “10 years later, the craziest Red Sox game of them all.”

50 Walter Zink, a right-hander from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, does not appear to have spent any time in the minor leagues. He had been unable to make his high school team in Pittsfield but developed in college at Harvard and Amherst and had been signed out of Amherst in June 1921. “Pittsfield Boys Joins Giants,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, June 22, 1921: 4. He pitched one inning against the Dodgers on July 6, giving up three runs (one earned) and then – 13 days later – three scoreless innings against the Pirates. He had neither a win nor a loss, but a career ERA of 2.25. After his brief stint with the Giants, he was released to the Indianapolis Hoosiers, but does not show in available team records. On August 10, he was released to San Antonio. Though he was recalled by the Giants under option in October, in March 1922 he decided to forego further opportunities in pro ball. The only mention of him in the Boston Globe was in July 1924 when he had pitched in a semipro game for the Lynn Cornets and struck out 14 of the Revere batters but suffered poor support and lost, 6-3. “Revere Humbles Cornets at Lynn,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1924: 4. The Boston Herald published an obituary that identified him as a graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Business who had gone on to become New England meat merchandising manager for the A&P Co. supermarket chain. “Walter N. Zink, of Quincy, 65; Retired A&P Official,” Boston Herald, June 13, 1964: 6.

51 Peter Abraham, “Notes,” Boston Globe, January 7, 2024: C6.

52 September 2024 interview. Zink does hear from the Red Sox, who have an active alumni program, both by mail and invitations to occasional events. “When the Red Sox come to town, I always reach out to the trainer. I’ll chat with him every once in a while. Raquel Ferreira was always a good friend there, always a person I could rely on. Craig Breslow was always one of my good buddies in Triple A.”

Full Name

Charles Tadao Zink

Born

August 26, 1979 at Carmichael, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.