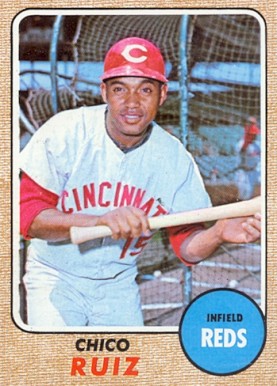

Chico Ruiz

Cuban infielder Giraldo Sablón – known in the U.S. as Chico Ruiz – ignited two tinderboxes. On September 21, 1964, his steal of home scored the game’s only run, starting the collapse of ten straight losses that cost the Philadelphia Phillies the National League pennant. On June 13, 1971, he waved a handgun in the clubhouse at troubled teammate Alex Johnson. This notorious incident – and its subsequent mishandling – was a flashpoint in one of baseball’s worst player relations debacles.

Cuban infielder Giraldo Sablón – known in the U.S. as Chico Ruiz – ignited two tinderboxes. On September 21, 1964, his steal of home scored the game’s only run, starting the collapse of ten straight losses that cost the Philadelphia Phillies the National League pennant. On June 13, 1971, he waved a handgun in the clubhouse at troubled teammate Alex Johnson. This notorious incident – and its subsequent mishandling – was a flashpoint in one of baseball’s worst player relations debacles.

Less than two months later, Ruiz played his final game in the majors. Six months after that, he died in an auto accident at the age of 33. Though his life was brief, one may define it by more than the steal, the gun, and the crash. Indeed, to focus on those events alone provides a distorted picture of the man.

Ruiz the player had a modest career, to be sure. He played in 565 games across eight major-league seasons, starting 238 of them. He was a utilityman: after coming up as a shortstop in the minors, he played mainly second base in the majors. He also played third, plus he filled in at first, the outfield, and even once for an inning at catcher. He brought five different gloves with him to the ballpark.1 He was speedy, leading four minor leagues in stolen bases – but he swiped just 34 in the big leagues. He also didn’t hit much at the top level: a .240 lifetime average with a slugging percentage of just .295.

Yet as a person, Ruiz was known for laughter and an amiable disposition, as Dick Miller wrote in The Sporting News after the fatal accident. Miller was the beat writer for the California Angels, with whom Ruiz spent his last two big-league seasons. He called Ruiz “everyone’s pal” and a “clown prince” – but compared him to Pagliacci, the sad clown. Ruiz once jested, “Bench me or trade me!” Still, Miller wrote, “It hurt that he wasn’t a regular with the Angels and Cincinnati.” Miller also touched on another issue that troubled many expatriate Cubans – Ruiz’s unsuccessful efforts to get his parents (and mother-in-law) out from under Fidel Castro’s regime.2

Giraldo Sablón Ruiz was born on December 5, 1938 in Santo Domingo, Cuba. This is a small city in what is now Villa Clara province, in the west-central part of the island.3 His father, Julio Sablón, operated a cigar factory.4 That business, Tabacos Hermanos Sablón, was founded by Julio’s father, Julián Sablón. Giraldo’s mother, Bárbara Ruiz Dreke, had four other children. There were two brothers, Julio and Gilberto, and two sisters, Irma and Yraida. After Castro came to power, Julio Sablón the younger eventually became head of the labor force of Cubatabaco, the state-owned tobacco company. The Communist government had confiscated the Sablón family business as part of its drive to nationalize the private sector.

In the Hispanic world, people formally bear double surnames, with each parent contributing half. The father’s family name is the primer apellido, or first last name, which male children carry across generations. Yet in the U.S., various Latino players have suffered from confusion, becoming known by the segundo apellido, or maternal family name. The Rojas Alou brothers from the Dominican Republic are one prominent example; Luis Rodríguez Olmo from Puerto Rico is another. In the case of Giraldo Sablón, it probably also came about the same way – a mistaken assumption when the player first came to the United States.

Confusion also arose over the spelling of his first name, which even Cuban sources show beginning with the letter H. In 1961, he told the story himself. “My father had to sign for me when I leave Cuba. He tell the immigration people my name is ‘Giraldo’ and they misunderstand. In Spanish ‘G’ is pronounced ‘H,’ so they think he mean ‘Hiraldo.’ Too much trouble to change now.”5

Cuban author Roberto González Echevarría has also expressed a firm view on another point. In fact, he said it was one of the motives for him to write his book The Pride of Havana. “Americans. . .bewildered Cuban fans by referring to [Sablón] as ‘Chico Ruiz,’ adding insult to injury by giving him a generic nickname. ‘Chico’ or ‘chica’ is one way Cubans (and other Spanish speakers) might familiarly call for each other’s attention, somewhat like ‘buddy’ or ‘mac’ in American idiom.’”6

For purposes of this biography, Ruiz will remain predominant because it was the name by which he was known while playing baseball in the United States. Exceptions are made for his youth and Cuban career. The use of “Chico” will be limited.

The young Sablón came to baseball at a very early age. In early 1964, he told reporters, “Where I live in Cuba, if baby is boy, his first gift is always a bat.”7 His speed was recognized in high school, when the track team’s coach saw him observing, invited him to join a sprint – and saw Giraldo win while running in bare feet.8

His father wanted him to take over the cigar factory, but upon graduating from high school, young Giraldo instead “entered college to study architecture. He completed three years at a Cuban college, concentrating on residential housing, and he [wanted] to go on for his degree at some U.S. university.”9

Sablón signed with the Cincinnati Reds in 1958. He was part of the pipeline of Cuban talent that Cincinnati enjoyed in the 1950s, thanks to the friendship between Reds general manager Gabe Paul and Bobby Maduro, the Cuban baseball man who owned the Havana Sugar Kings (which became Cincinnati’s top farm club in 1954). As The New Bill James Historical Abstract put it, “A man named Tony Pacheco [who both played for and managed the Havana club] was scouring the island on behalf of the Sugar Kings. . . Pacheco put together a team of about fifteen young players who traveled Cuba, playing a schedule of exhibition games. On that team were Diego Seguí, Tony González, Chico Ruiz, José Tartabull, and Tony Pérez.”10 The only one of that group who did not sign with Cincinnati was Tartabull. Cuban baseball writer Andrés Pascual also points to the role of Corito Varona, another scout who was active in Cuba for the Reds at that time.11

The 19-year-old Ruiz’s first professional action came with Geneva of the NY-Penn League (Class D) in 1958. He hit reasonably well, though without power (.251 with no homers and 31 RBIs). His fielding statistics are unavailable, but judging from the 1960-62 period, he probably made a lot of errors. One may also infer that he got to a lot of balls with his speed. He stole 29 bases, good for second in the league.

In the winter of 1958-59, under the name Sablón, he played in the Cuban winter league for the first time. He got into seven games for the Cienfuegos Elefantes, a team that had Leo Cárdenas at shortstop, Oswaldo Álvarez at second base, and John Goryl at third base. Octavio “Cookie” Rojas was the main infield reserve but got just 89 at-bats. Sablón was hitless in a mere two at-bats. Andrés Pascual wrote, “He [Sablón] was projected as a player capable of reaching the big leagues if a problem with a dislocated throwing shoulder could be fixed, which it was.”12 The injury came while sliding, apparently headfirst.13

Ruiz stepped up to Class C for the summer of 1959. With Visalia in the California League, his batting line was .252-5-44 in 137 games (again, no fielding record is readily available). He led his league in steals with 61.

He then returned to Cienfuegos for the 1959-60 season. Even the local correspondent for The Sporting News was prone to confusion, listing the player’s name as “Humberto” Sablón. Cuban baseball author Jorge Figueredo put forth this Elefantes squad as possibly the greatest in the nation’s history.14 Cárdenas and Álvarez were again the starting double-play combo, with Rojas in reserve. The third baseman that season was Don Eaddy. Again Sablón played sparingly, going 3 for 14 in 20 games. Cienfuegos ran away with the league title that year and then swept the Caribbean Series – the last time Cuba participated. Sablón got into two games, going 1 for 2.

The Reds promoted Ruiz to Single-A for 1960. It is interesting to note that he “started as a lefty hitter in 1958, batted strictly righty in ’59, and then became a switch-hitter [in 1960].”15 That was the suggestion of Max Macon, his manager with Columbia of the Sally League. Ruiz lifted his average to .290, hitting 4 homers and driving in 44. His league-leading 55 steals broke a club record that had stood since 1906.16 However, he also committed errors by the bushel: 61 in 137 games. Nonetheless, he was co-MVP of the league. Cincinnati placed Ruiz on the roster of its Triple-A affiliate, Indianapolis, after the season. He was rated among “the cream of the crop” of the team’s prospects.17

The 1960-61 season was the last for Cuban professional baseball; after that, the Castro regime abolished the league. Only Cubans played that winter, and Sablón finally got a good measure of playing time – at third base. He hit .274 (45 for 164) in 41 games, with no homers and 8 RBIs.

As leadoff man with Indianapolis in 1961, Ruiz hit .272-3-50 in 147 games, leading the American Association with 44 steals. A hot stretch in July won him a Topps Player of the Month award, which he had earned once previously with Columbia. He also received attention as a possible MVP candidate, “either through brilliant fielding, a hot bat, or his streaking legs.”18

Cincinnati won the National League pennant in 1961 (as Indianapolis did in the American Association). During the stretch drive, the Reds were interested in obtaining veteran catcher Sherm Lollar from the Chicago White Sox. Lollar cleared waivers, but the White Sox wanted Ruiz, and Reds general manager Bill DeWitt declined, calling it “too much. . .Ruiz [is] our best prospect in the minors.”19 With Ruiz in the wings, Cincinnati mulled trading Leo Cárdenas, who was one of the big club’s shortstops.

Ruiz married Isabel Suárez Navarro on October 4, 1961.20 They later had two daughters, Isis and Bárbara Isa. In the absence of Cuban winter ball, the newlywed played in the Florida Instructional League in the winter of 1961-62. Ruiz had committed 44 errors in 1961, yet Harry Craft, the manager of the Houston Buffaloes (an AA opponent), said, “Ruiz can go farther to his right for ground balls than any shortstop I’ve ever seen. And he’ll throw out a fast runner. The way he can field, he won’t have to hit too much.”21 Ruiz then went on to join the San Juan Senadores in the Puerto Rican Winter League, playing third base again. Meanwhile, DeWitt again refused to include the prospect in trade proposals.

There was much talk that Ruiz might make the majors in 1962. In spring training that year, he said with his usual wide grin, “If they say I have to catch to stay in the major leagues, then I catch.” Cincinnati manager Fred Hutchinson said, however, “If Ruiz can’t win a regular job this spring, we won’t keep him. He’s too young and has too much potential to sit around on the bench as a spare infielder.”22 Ruiz even won a comparison to Luis Aparicio.23

So he spent that season and the next with the Reds’ new top farm club, the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League. In his Ruiz obituary, Dick Miller quoted Eddie Leishman, the Padres’ general manager. “He was a great local favorite because of his hustle and enthusiasm,” said Leishman. “Every time he would walk into the office, people would smile. They always were glad to see him.”24 The feeling was mutual; Ruiz made his home in the San Diego area.

Continuing as a leadoff man, Ruiz hit .283-5-43 in 1962, although his error total rose again to 54. Many of those came in the early part of the season, however, and his hitting picked up later too, helping the Padres win the PCL championship. Once again he led his league in steals, this time with 40. He returned to Puerto Rico that winter, this time with the Santurce Cangrejeros, and the local sportswriters named him to the league’s all-star team at shortstop.

After that season ended, he paid a visit to the Virgin Islands. 25 For many years there, a local all-star team faced a group of players from the PRWL after the Puerto Rican season ended. That year the V.I. squad – featuring Elrod Hendricks, Valmy Thomas, and Elmo Plaskett – won two out of three games in an upset. The Virgin Islands Daily News wrote, “Silenced in the series were the big guns from Puerto Rico. Orlando Cepeda, the much feared Giants slugger, couldn’t deliver any of the big hits that were expected of him. . .It was the little guys who provided most of the excitement on the Puerto Rican team. Chico Ruiz got on base more times than expected.”26

The development of Leo Cárdenas meant that Ruiz was now on the trading block, although Bill DeWitt said, “We’re not going to give Ruiz away just because we don’t plan to use him in 1963. When clubs talk about Ruiz, they’re talking about the best shortstop in the minor leagues in 1962. If I just wanted money, I could get $150,000 for him today.”27

Ruiz returned to San Diego in 1963, reaching double digits in homers for the only time as a pro (11), while driving in 46 and hitting .298. For the fifth time in a row, he led his league in steals (50) – and it would have been more had a pulled leg muscle not hampered him for much of the season. Perhaps even more impressive was the sharp reduction in his errors (just 15). That year, though, he played more at third base than at short, where most of the time went to Tommy Helms.

That performance made Ruiz a “cinch to stick” with Cincinnati in 1964, according to Bill DeWitt – but most likely in a utility role.28 Although the Reds tried various players at third base until Tony Pérez took over in 1967, Pete Rose had emerged as Rookie of the Year at second base in 1963. Leo Cárdenas remained the incumbent at short through the 1968 season. Since Cárdenas was also called “Chico” in the U.S., he became “Chico One” when “Chico Two” – Ruiz – made the big club at last. 29 Ruiz was coming off another winter with Santurce, followed by a stint as a playoff reinforcement with Escogido in the Dominican League.

As it turned out, Ruiz won the starting job at third in spring training 1964, largely due to his speed and defense. He played 21 games there but was sent back to San Diego because of weak hitting (.213-1-5). The rookie returned in late July, mainly filling in at second base for Rose.

The events of September 21, 1964 have been chronicled in depth many times. A sidebar article – “In Defense of Chico Ruiz’s Mad Dash” – appeared in the SABR BioProject’s book on the 1964 Phillies. Thus, a briefer overview will suffice here – with an emphasis on what Ruiz himself thought and said. Coming into the game, Philadelphia still held a comfortable 6½ game lead over Cincinnati and St. Louis. At Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium, John Tsitouris and Art Mahaffey were in a scoreless mound duel. After Pete Rose grounded out to lead off the top of the sixth, Ruiz singled and went to third as Vada Pinson singled off Mahaffey’s glove; Pinson was thrown out at second base trying to stretch his hit into a double.

Frank Robinson – the Reds’ best hitter – came to the plate. The count was 0 and 1 when Ruiz lit out for home plate, entirely on his own. The Associated Press recap showed what sparked the play that “surprised everyone in the ballpark, including me,” as Reds manager Dick Sisler put it. “It just came to my mind,” Ruiz said. “In this game either you do or you don’t. With a hitter like him (Robinson) at the plate, you better make sure you make it or you get heck.” He said he got the idea when he saw Mahaffey take a long windup on the first delivery to Robinson.30

When Mahaffey saw Ruiz make his break, he “vapor locked” and heaved his pitch wide. Phillies manager Gene Mauch railed after the game, “Chico F***ing Ruiz beats us on a bonehead play of the year!” Twenty-five years later, Philadelphia sports columnist Stan Hochman described it more elegantly: “Ruiz stealing home with Robinson at bat was so impetuous, so implausible, so impossible to justify.”31 Yet by forcing the action, Ruiz rattled Mahaffey and brought about a favorable outcome. Even catcher Clay Dalrymple, who also dismissed the play as stupid, acknowledged “the shock of it all.”32 It was a guerrilla tactic right out of the Ty Cobb or Jackie Robinson playbook. But even with the great Frank Robinson at the plate, sabermetric analysis shows that it was not a bad percentage move.33

As Cincinnati went on to sweep the series, Ruiz endured Mauch’s bench jockeying (accounts that Mauch ordered Ruiz to be drilled in the ribs with a pitch may not be plausible).34 In the third game, on September 23, he hit his second and last major-league homer. It came off Dennis Bennett and tied the score at 1-1. The Reds vaulted past the Phillies a few days later, before both were ultimately overtaken by the St. Louis Cardinals.

In the winter of 1964-65, Ruiz went to a new place to play winter ball: Venezuela. He wanted $1,500 a month but had to settle for $1,000 because Commissioner Ford Frick had agreed upon salary terms with the Caribbean winter leagues.35 It was interesting that he was even allowed to go, because starting in 1962-63, Frick had mandated that Latino ballplayers could not play anywhere other than their home country in the winters. This hit Cubans (such as Tony Taylor and Tony González) particularly hard. It’s not certain why Ruiz was exempt.

After 1964, Ruiz never got as many at-bats (311) again in the majors. Though he spent the entire 1965 season with the Reds, he was the last man on the bench. He got into just 29 games, most as a pinch-runner – he played in just seven games in the field and was just 2 for 18 with the bat. His season ended on August 25 when he broke his ankle while sliding into third base as a pinch-runner. Isabel gave him a playful hard time about the accident. As Ruiz later recalled, “When I called my wife after breaking my leg in Milwaukee, she asked me if I had fallen off the bench while I was asleep.”36

Ruiz got somewhat more frequent duty over the next four seasons with Cincinnati. He averaged 90 games played from 1966 through 1969, with a career-high 105 in 1967. He made 189 plate appearances on average during this period, and his .240 batting average was right in line with his career norm. Yet despite his modest on-field contributions, he still made good copy for sportswriters, as A.J. Friedman of the Toledo Blade showed in June 1968. Ruiz told Friedman, “I make my money and do my playing in the winter and just work out during the summer.” He also talked about his little hobbies: decorating the clubhouse with stars made out of chewing-gum wrappers, giving hotfoots, and relaxing with his matched set of Ruiz Bench Special foam-rubber cushions (“Extra soft for single games” and “Extra nice for doubleheaders”).37

Deeper insight into this period comes from an August 1969 feature in Sports Illustrated about utilitymen called “The Bottom of the Lineup.” Writer Gary Ronberg focused mainly on Ruiz, offering more of his amusing antics – but also quoting him in a serious vein on how he kept game-ready and still hoped for a chance to play regularly (though this article was where the “Bench me or trade me!” line came to attention). Ruiz said, “If the chance comes and I blow it – well, I can always say I was a pretty good utility player. But if that chance never comes, it will hurt. It will hurt very much.”38

As Friedman noted, Ruiz continued to play winter ball. In Venezuela, he joined La Guaira in 1965-66 after recovering from his broken ankle. He was a member of the league champions that year. After two winters with the Tiburones, he played in the Dominican Republic for Estrellas Orientales in 1967-68. The manager was old friend Tony Pacheco. Also there was Harry Walker, batting instructor for the Houston Astros who was working with some of the team’s prospects in winter ball. “The Hat” issued his standard advice: use a heavier bat and slap at the ball.39 Ruiz was part of another champion team that winter; the Estrellas club did not win another Dominican title until 2019.

Ruiz returned to Venezuela in the winter of 1968-69, joining the Caracas Leones for a year, and then spent one more with Navegantes de Magallanes. The 1969-70 playoffs were an oddity; Ruiz played with Magallanes in the semifinal round but switched to La Guaira for the finals, and the Tiburones lost. In his five Venezuelan seasons, Ruiz got into 258 games, batting .270 with 4 homers and 86 RBIs and stealing 38 bases.

Venezuela was where Ruiz acquired a special accessory: his alligator spikes. He said in June 1967, “You sit on the bench, you have to look pretty.”40 The following June, he also told A.J. Friedman “They’re not a good running shoe. I have a pretty good idea when Dave (manager Dave Bristol) is going to put me in the game. Then I take these off and put on my regular spikes.”41

Ruiz was playing for Magallanes when Cincinnati traded Alex Johnson and him on November 25, 1969. They went to the California Angels for Pedro Borbón, Vern Geishert, and Jim McGlothlin. Press accounts portrayed the talented Johnson and McGlothlin as the key figures in the deal, though over time Borbón’s career proved to be the most valuable.

During the 1970 season, Ruiz – by then 31 – got into 68 games for the Angels. He hit .243 in 120 plate appearances. His playing time was so scanty early in the season that Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times called him, “the only season ticket holder with a number.” Yet Murray also described how Ruiz took his teammates’ ribbing and the lack of action without any bitterness.42 The handyman played all around the infield that year, and he finally got to use his catcher’s mitt in a big-league game on August 19 at Anaheim Stadium.

The Alex Johnson affair by far overshadowed Ruiz’s minimal on-field action in 1971. Johnson and Ruiz had been teammates with the Reds in 1968 and 1969 before they were traded together, and they became close enough for Ruiz to stand as godfather when Johnson and his wife adopted a little girl whom they named Jennifer. The friendship had begun to sour in 1970, though. On September 14 that year, the Los Angeles Times reported that they scuffled in the batting cage; “it started when Johnson lashed into Ruiz with a string of obscenities.”43

The abuse continued in 1971 – as Mark Armour wrote in his SABR biography of Johnson, Players Association head Marvin Miller believed that Johnson was emotionally disabled. The situation came to a head on June 13 after both players had served as pinch-hitters and had left the game. Johnson said, “He [Ruiz] brought a gun to the clubhouse. He had been talking all year that he was going to bring a .38 to the park and kill me. You can take it from me, he threatened me with a gun. He’s crazy.”44

Ruiz vehemently denied the accusation, saying that he didn’t even own a cap pistol. The Angels front office, notably general manager Dick Walsh, also sought to whitewash the event. On August 29, though, Walsh “admitted under oath that he knowingly falsified the truth and ordered that the weapon be concealed so it would not be found.”45 Ruiz too eventually made his thoughts on the matter known, according to another of his obituaries. Don Merry of the Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram wrote, “Privately, Ruiz admitted brandishing the weapon but steadfastly denied pointing it in Johnson’s direction. ‘I was growing tired of his constant badgering. I only wanted to let him know that I was serious when I asked him to stop.’”46

Ruiz made his last appearance in the majors on August 3, 1971. Not surprisingly, it was as a pinch-runner. He had started only one game all year and played in the field in just five of 31 outings. A couple of weeks later, Jim Fregosi, whose injured foot had healed, came off the disabled list. The Angels then demoted Ruiz to Triple-A. Dick Miller wrote that “a personality conflict had long existed between the manager and his player. . .[Lefty] Phillips looked with disfavor on Ruiz’ clowning and rapport with fans.” Ruiz himself remained gracious and good-humored, but remarked, “I’m not surprised by this. I’ve had a Salt Lake City schedule in my wallet for several weeks.

“Baseball is like a war,” he also said. “You have to fight to survive. . .I didn’t get a chance to fight so now I die.”47

At Salt Lake, Ruiz played in just eight games. At the end of the 1971 season, the Angels put him on the roster of their Single-A farm club in Davenport, Iowa. That December, the Kansas City Royals drafted him for their Triple-A affiliate in Omaha. Royals GM Cedric Tallis later said, “Chico was going to be a backup man in our infield. I’m sure he would have made the big league club.”48

With Eddie Leishman as sponsor, Ruiz became a U.S. citizen on January 7, 1972, something that made him very proud. Just over a month later, on February 9, he had his fatal accident.

On the last day of his life, Ruiz played baseball for the San Diego Padres – with whom he had been working out in preparation for spring training – against Mesa Junior College. According to Leishman, one player got sick and another had to go to Los Angeles to see a doctor. At the last minute Roger Craig (then the pitching coach for San Diego) invited Ruiz to play, and he got four at-bats. That prompted a teammate to joke, “That’s more times than you were up with the Angels last season.” Leishman said, “Chico just laughed.”49

Driving alone on Interstate 15 – at a speed estimated between 70 and 80 miles per hour – Ruiz lost control of his car about a mile from his home in the town of Rancho Peñasquitos. He hit a signpost and was pronounced dead on arrival at Palomar Hospital.50 He was buried in San Diego’s El Camino Memorial Park. Alex Johnson and his wife attended the funeral. Dick Miller wrote, “The longtime friends battled furiously last season, but friendship won out in the end.”51

More than 40 years after his death – and over half a century after his astounding steal against the Phillies in 1964 – the memory of Chico Ruiz lingers. That is especially true in Philadelphia, where his “ghost” is still invoked as a symbol of failure for the city’s sports teams. “Curse” is also an ongoing association with Ruiz’s name, both in Philadelphia and Anaheim, where the Angels have suffered an unusual number of premature player deaths over the years.

A happier way to remember this man is for his effervescent character. Chico Ruiz was part of a long-running (though now diminished) tradition of baseball entertainers. Twice Joe Garagiola invited him to appear on the Today Show. Like another Caribbean player of the time, pitcher Al McBean, Ruiz said that he liked to do “crazy little things.” McBean and Ruiz shared a love of mingling with fans and bringing a sense of fun to the game. It was also about keeping teammates loose and maintaining a good attitude.52

Special thanks to Isabel Sablón Díaz, widow of Giraldo Sablón a.k.a. Chico Ruiz, for her input (via e-mail, April 25 and April 26, 2019).

Continued thanks to SABR member José Ramírez and Andrés Pascual for their input. Thanks also to SABR member Shane Tourtelotte and Dan Turkenkopf for insight on quantifying Ruiz’s steal of home on 9/21/1964.

Sources

Internet sites

http://www.baseball-reference.com

http://www.retrosheet.org

http://www.purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics)

Books

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003.

Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005.

Notes

1 Jim Murray, “Chico Ruiz…The Only Season Ticket Holder with a Glove,” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1970.

2 Dick Miller, “Ruiz, Everyone’s Pal, Killed in Auto Crash,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1971, 38, 40.

3 The former province of Las Villas was subdivided during the Castro era.

4 Gary Ronberg, “The Bottom Part of the Lineup,” Sports Illustrated, August 25, 1969.

5 “Let’s Just Call Him Chico,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1961, 26.

6 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, 8.

7 Doug Wilson, Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010, 131.

8 Earl Lawson, “Barefoot Ruiz Zipped Past Sprinters on Track Team,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1964, 5.

9 Ronberg, “The Bottom Part of the Lineup” (names of the schools attended are not presently known)

10 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract, New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001, 437.

11 Andrés Pascual, “Hiraldo Sablón, El Chivo Expiatorio de Gene Mauch,” Béisbol 007 blog, July 15, 2012 (http://beisbol007.blogia.com/2012/071502-hiraldo-sablon-el-chivo-expiatorio-de-gene-mauch.php)

12 Pascual, “Hiraldo Sablón, El Chivo Expiatorio de Gene Mauch”

13 E-mail from Andrés Pascual to Rory Costello, September 8, 2012.

14 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005, 463.

15 “Tribe’s Ruiz Draws Raves,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1961, 24.

16 “Ruiz Sets Columbia Mark With Theft Of 54th Base,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1960, 37.

17 Earl Lawson, “Shoppers sound Out DeWitt on Reds’ Players,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1960, 26.

18 Les Koelling, “Flashy Ruiz Paces Indian Flag Drive,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1961, 15.

19 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1961, 10.

20 Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965. The September 3, 1966 issue of The Florida Star gives October 7 as the date (http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00028362/00730/9j).

21 Earl Lawson, “Ruiz, Reds’ Cuban Comet, Wears Quick-Comer Label,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1961, 26.

22 Earl Lawson, “Red Speedster Ruiz Dazzler on Defense, Artist with Bludgeon,” The Sporting News, March 14, 1962, 23. That article was also notable for the biased compliment that Harry Craft paid Ruiz: “Many of the Latins have a tendency to loaf now and then, but Ruiz runs out everything.”

23 Bob Burnes, “Big Timers Scramble to Fill Key Berths,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1962, 7.

24 Miller, “Ruiz, Everyone’s Pal, Killed in Auto Crash,” 40.

25 It wasn’t the first time he had played there. In 1957, while barnstorming with a Cuban team before turning pro, he had played catcher in a game. He noted this when in line to serve as emergency catcher with Cincinnati in 1964. Earl Lawson, “Desperate Reds Pay 30 Gees for Backstop Coker,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1964, 13.

26 “VI Stars Whip Puerto Rico; Take Two Out of Three Games,” Virgin Islands Daily News, February 13, 1963, 12.

27 “Wendell Smith in Chicago’s American,” The Sporting News, January 5, 1963, 35.

28 Earl Lawson, “‘No Red Swap Panic,’ DeWitt Vows,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1963, 27.

29 Wilson, Fred Hutchinson and the 1964 Cincinnati Reds, 130.

30 “Ruiz’s Steal Shocks Phils – and Reds,” Associated Press, September 22, 1964. Sources vary as to the count when the play took place. Art Mahaffey later remembered it as 0 and 2, but two of the books that chronicle the 1964 Phillies’ season support the AP recap.

31 Stan Hochman, “Art Mahaffey,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 17, 1989

32 Stan Hochman, “Clay Dalrymple,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 17, 1989.

33 Analysis derived from the Hardball Times Win Probability Inquirer, which may be found at http://www.hardballtimes.com/thtstats/other/wpa_inquirer.php.

34 If Mauch had wanted to send a message, it seems more likely that he would have done it in Ruiz’s first at-bat. Ruiz did get hit by a pitch that day, but it was the eighth inning, and Cincinnati was already ahead 9-1.

35 Eduardo Moncada, “Frick’s Decision Blocks Ruiz’ Bid for Higher Pay,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1964, 35.

36 Earl Lawson, “Chico’s Wife Was Quick to Give Husband Needle,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1966, 26.

37 A.J. Friedman, “At Home On The Bench,” Toledo Blade, June 9, 1968, B-3.

38 Ronberg, “The Bottom Part of the Lineup”

39 Earl Lawson, “Ruiz, Prize Walker Student, Now ‘Harry’ to Reds Pals,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1968, 12.

40 Hal Bock, “Old Ruse Still Good,” Associated Press, June 17, 1967.

41 Friedman, “At Home On The Bench”

42 Murray, “Chico Ruiz…The Only Season Ticket Holder with a Glove”

43 Ross Newhan, “Johnson, Ruiz Scuffle; Angels End Slump, 2-1,” Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1970, D-1.

44 Alex Kahn, “Angels’ Johnson Says Ruiz Pulled Gun in Clubhouse,” United Press International, June 15, 1970.

45 “Say Exec Lied in Johnson Case,” United Press International, September 8, 1971.

46 Don Merry, “Chico Ruiz–More Than Utility Man,” Independent Press-Telegram (Long Beach, California), February 10, 1972, C-3.

47 Dick Miller, “Angels Send Ruiz to Minors, but They Can’t Erase His Grin,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971, 11.

48 “Chico Ruiz Dies in Highway Accident,” Associated Press, February 10, 1972.

49 Miller, “Ruiz, Everyone’s Pal, Killed in Auto Crash,” 40.

50 “Chico Ruiz Dies in Crash,” Associated Press, February 10, 1972. Some versions of the story said he was traveling on Interstate 5, which also runs through the San Diego area, but I-15 goes right by Rancho Peñasquitos.

51 Miller, “Ruiz, Everyone’s Pal, Killed in Auto Crash,” 40.

52 John Wiebusch, “Ruiz’ Role: Keep Players Loose,” Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1970, B1. Rory Costello, “Al McBean,” SABR BioProject (http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/2207fa33). Ronberg, “The Bottom Part of the Lineup.”

Full Name

Giraldo Sablón Ruiz Sablon

Born

December 5, 1938 at Santo Domingo, (Cuba)

Died

February 9, 1972 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.