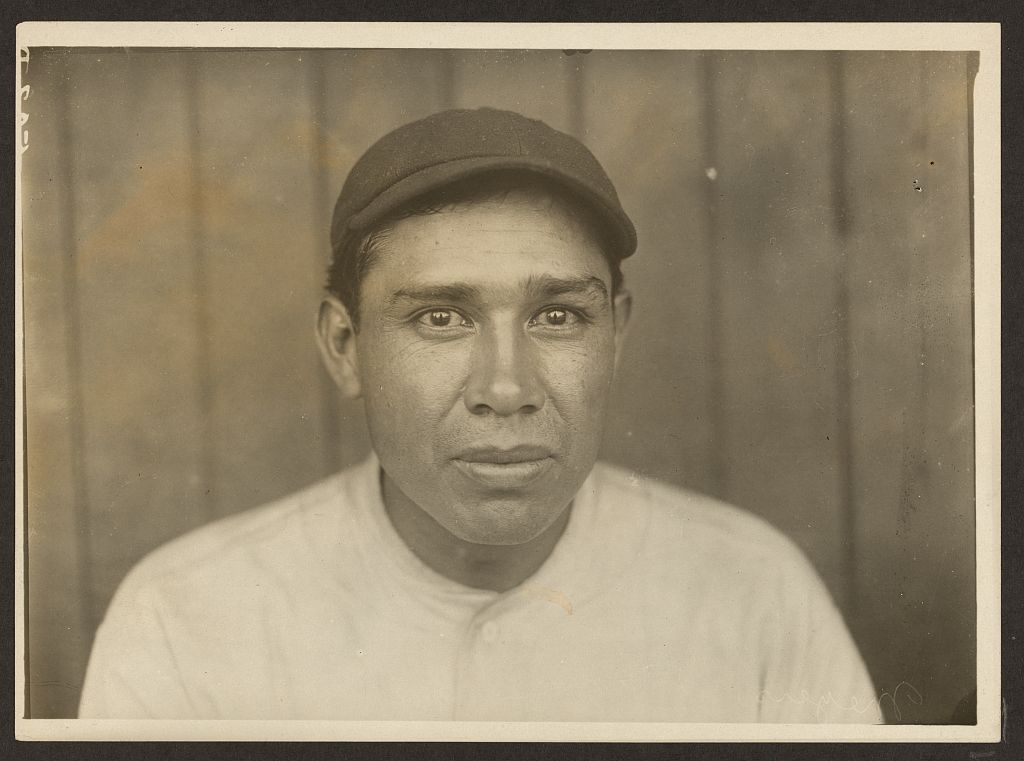

Jack Meyers

As a Native American playing in the Deadball Era, Jack Meyers couldn’t avoid being saddled with the nickname “Chief,” but he did as much as any Native American of his generation to battle the stereotypes. Sportswriters who covered Meyers found him to be far more sophisticated than most of his fellow players. One reporter wrote in 1909, before Meyers had even played one major-league game: “A strong love of justice, a lightning sense of humor, a fund of general information that runs from politics to Plato, a quick, logical mind, and the self-contained, dignified poise that is the hallmark of good breeding – he is easily the most remarkable player in the big leagues.”1 On the field, Meyers was one of the top offensive catchers of the Deadball Era, retiring with a .291/.367/.378 slash line for his nine-year career, and was a deft handler of pitchers.

A member of the Cahuilla Band (pronounced ka’-weeyu),2 John Tortes Mayer was born on July 29, 1880, in Riverside, California. His mother, Felicité, raised him, his brother, Marion, and his sister, Christine, alone after her husband, John Mayer, died in 1887.3 They lived for a time on the nearby Santa Rosa Reservation, where John and Marion learned baseball. (Marion, one year older, was a pitcher until an accident cost him sight in one eye.) Felicité moved her family back to Riverside when John was 11. He attended Riverside High School and caught for the high-school team. At some point, attributed to a school administrator’s action, the surname of John and his siblings was changed from Mayer to Meyers.4

When John was 13, he was recruited for a company team for the Santa Fe Railroad. The organizer, John Lightfoot, hired most of the players to easy jobs with the railroad. John, now using Tortes as his surname, went to the boiler room. In a 1961 interview, he said, “I loved the work,” and added that swinging a heavy sledgehammer built up his muscles.5 Over the next decade, he built his 5-foot-11-inch frame to nearly 200 pounds.6 He worked for a number of mining and copper companies in Arizona and California and, naturally, played baseball with the company teams. He also played in the California winter leagues, which included experienced professional players.7

While catching for a Clifton, Arizona, baseball team representing the Phelps-Dodge Copper Company, he played in a summer tournament for semipro clubs, held in Albuquerque. There he met a Dartmouth College student, Ralph Glaze, who played for a rival team (auspiciously enough, named Big Six.) Glaze starred in both baseball and football at Dartmouth and would later make the major leagues as a pitcher. Thinking the big catcher could help Dartmouth in both sports, Glaze recruited John, pointing out that Dartmouth’s charter provided for the education of Native Americans.8

After the tournament, Glaze returned to his hometown of Denver with the catcher in tow. There he enlisted the aid of businessmen and Dartmouth alumni, who equipped the new recruit with cash, railroad tickets, and clothing. John, though intelligent and literate, had not completed high school, and so they also provided an altered diploma for him under the name of Ellis Williams Tortes, combining his mother’s maiden name with the name of a Clifton teammate. The ersatz diploma gave his birth year as 1883, making him three years younger than he actually was.9

With the assistance of a tutor, Meyers attended classes at Dartmouth during the 1905-06 school year. Meyers loved Dartmouth. He joined a fraternity and engaged in campus society. For the rest of his life, he spoke fondly of his time there, though he hated the New Hampshire winters, and his grades suffered due to his abbreviated early schooling and his worries over the health of his mother in California. He enjoyed putting his classmates on with fanciful stories of Indian life,10 a pastime he indulged in for most of his years. It should be noted, as did one biographer, that Meyers “must be considered the suspect source of some of the inaccurate, even bizarre, published references to his ethnic origins.”11

Eventually, the school administration discovered that Tortes’ high-school diploma was false. The college president contacted the school that issued the original diploma, then summoned Tortes and Glaze to his office and confronted them with the deception.12

Dartmouth, however, offered to admit Jack after he completed a program at a preparatory school. He declined; he was already significantly older than his classmates. However, Tommy McCarthy, the former ballplayer and Dartmouth baseball coach, recommended Meyers to Billy Hamilton, manager of the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) club of the Tri-State League.13

In a 1909 newspaper interview, Meyers said the Harrisburg team “certainly laid themselves to make me a happy Indian. I went to the clubhouse … and nobody paid more attention to me than they did to the batbag.”14 It didn’t help that the one person who knew Meyers, Hamilton, resigned on June 22, 1906, the day Meyers arrived. Meyers had a lone pinch-hitting appearance, before finally getting to catch in the second game of the Fourth of July doubleheader. Unfortunately for him, he was assigned to catch spitball pitcher Frank Leary. Meyers had never handled a spitball pitcher before. “I was getting it everywhere but in my glove. I had five passed balls in two innings.” However, Meyers, in that 1909 interview, continued: “Do you know, that did me more good than anything that ever happened to me? It made me mad. I had been timid and now I was mad enough to be brave.” Meyers chewed out the manager, Jack Calhoun, for putting him into a game in that situation. The manager admitted Meyers was right, and after that, Meyers found the courage to stand up to the other players as well. “I had an easier time” after that point, he said.15

Things might have looked that way from his 1909 viewpoint, but the path to acceptance appears a little twistier than Meyers let on. For one thing, Harrisburg released Meyers on July 10, claiming a surfeit of catchers.16 However, the Lancaster club snapped up Meyers right away, needing to replace a hospitalized backstop.17 Meyers caught regularly and started hitting, doubling in the game-winning run against Williamsport on July 22.18 When Lancaster released Meyers in August (presumably because its regular catcher returned to action), Harrisburg had a change of heart and signed him back to close out the season.

Meyers’ copper company connections probably helped him land a berth in the Northwestern League with the Butte, Montana, club in 1907.19 His play sparkled; a Seattle newspaper reported that Meyers “is about half the Butte team, for he keeps the runners hugging the bases and besides, he can clout the leather high and far away.”20 He returned to California for the winter ball season. With the Pickwicks of the Southern California State League, Meyers participated in a postseason series against the Los Angeles Angels. In this series, he caught Walter Johnson, who fanned 16 Angels and won 1-0 in the first game of the series.21

Meyers then moved to St. Paul in 1908 and caught fire there too. He was leading the American Association in batting on June 28, with a .319 average.22 Three days later, the Giants shelled out $6,000 for his contract.23 It would have been a record price except for the Giants purchasing Rube Marquard for $11,000 the same day. Meyers was called to New York but saw no regular-season action during the tumultuous end of the 1908 season.

Despite the price tag, Meyers was no shoo-in for playing time. It’s true that Roger Bresnahan, the popular catcher of the 1908 squad, was traded that offseason to St. Louis, where he could be a player-manager. However, as part of the deal, the Cardinals got Admiral Schlei from the Reds and sent him along to New York. Schlei had been Cincinnati’s regular catcher in 1908 and he and Art Wilson were supposed to do the bulk of the catching, with Meyers and Fred Snodgrass vying for the third spot and learning the ropes.

But Giants fans immediately took a liking to Meyers. He socked two home runs in the annual exhibition game with Yale, his Polo Grounds debut, on April 10, 1909.24 His first official major-league appearance was as a pinch-hitter on Opening Day, five days later, a game in which hard-luck pitcher Red Ames pitched 12 innings of shutout ball only to watch the Giants batters post 12 goose-eggs of their own. Brooklyn took a 3-0 lead in the top of the 13th. Frustrated by their team’s poor showing at the plate, Giants fans shouted, “Put in the Indian!” and “Give us Meyers. He can hit a ball.” Pinch-hitting for Ames in the 13th inning, Meyers notched his first major-league hit.25

Two days after that, Meyers took his place behind the plate to catch Rube Marquard’s second career start. The $17,000 battery held the Phillies to three hits and a run in their first victory together.26 Giants manager John McGraw seemed to like the way Meyers caught Marquard, and paired them up for four of Rube’s next five starts. All were one- or two-run losses except for a win over Chicago on May 12, in which Meyers earned more plaudits with his bat, driving in the game-winner in the bottom of the ninth. Ring Lardner naturally resorted to the soft-core bigotry of the time in his game story the next day: “Big Chief Meyers, he break up big ball game with heap big triple in big ninth inning. Yes. He shoot Cubs full of heap big holes today.”27 That sort of thing. By now, Meyers had worked his way ahead of Wilson, and Lardner thought it remarkable that Meyers would work two days in a row, even though Schlei was feeling all right. Meyers worked a third straight day on May 13, catching Christy Mathewson for the first time.

Meyers’ defense and arm were not as good as Schlei’s, true, but Meyers made up for it with his bat and his brains. In his first big-league season he hit .277 to the Admiral’s .244. Schlei caught 89 games in 1909, but Meyers caught 64, including 20 of Mathewson’s 33 starts. Mathewson liked working with Meyers. The two clicked in that May 13 game, which was just Mathewson’s second start of the season. They clicked again four days later for a six-hit shutout. The two rarely quibbled over pitch selection. Meyers was, like Matty, an able student of opposing batters and the two got into a rhythm quickly. The other pitchers, reluctant at first to work with the unknown Meyers, took their cue from Big Six.

By 1910 Meyers was the regular backstop, catching 117 games and batting .285. The only pitcher Meyers did not catch was Bugs Raymond, the spitballer. After a pitch from Raymond split a finger on Meyers’ throwing hand, McGraw said, “From now on, you don’t catch spitballers. You’re the catcher for Mathewson and Rube and anybody who throws regular pitches.”28 That season, Wilson and Schlei saw little action, and Snodgrass, with no future as a catcher, moved to the outfield.

The press, in New York and elsewhere, took an immediate liking to Meyers because he made more interesting copy than his teammates. During rainouts or offdays, while the other players holed up playing cards or billiards, newspapers reported that Meyers would go out to do some historical sightseeing or watch a local college football team practice. In Boston, wrote Bozeman Bulger, Meyers made a point of visiting the art museums where he spent hours touring the exhibits. Several writers noted his favorite paintings: “Quest for the Holy Grail,” the mural by Edwin Austin Abbey that hangs in the Boston Public Library; and “Custer’s Last Fight” by Cassilly Adams. When asked why the latter, Meyers would say “[I]t was the only picture he ever saw where the Indians were getting as good as an even break.”29

Meyers became so popular with the fans in New York and around the league that the vaudeville circuit took notice. Mathewson and Meyers received either $1,500 or $2,000, combined, to appear with actress May Tully on the vaudeville circuit. They opened at Hammerstein’s Victoria on October 23, 1910.30

What must it have been like for Meyers, appearing on stage with the national idol Christy Mathewson after only two full seasons in the big leagues? Well, given the state of American entertainment in the early twentieth century, it was a mixed blessing.

Ballplayers routinely appeared on the vaudeville circuit during the offseason. For baseball fans around the country, in the days before television and radio, vaudeville brought their favorite ballplayers to them. Occasionally a player might actually have possessed some talent for the performing arts. This was unusual, however. Most players had about as much talent for acting or singing as actors and singers did for baseball. That was not the point; the point was to hold the ballplayers up for display, and for the public to pay to see them. On the other hand, American entertainment is a mirror of American culture. Blatant racism and sexism were taken for granted in print and on the stage during this period (and since).

And so, Mathewson and Meyers performed a half-hour sketch called “Curves,” written by Bulger and produced by Tully. In this sketch, Tully plays an ardent spectator at the Polo Grounds. The Variety reviewer described the scene:

In “Curves,” Matty and his star catcher appear first as themselves warming up to go into a game that Hooks Wiltse is seemingly about to lose – off stage. They are in the clubhouse, and Miss Tully rushes, as is customary for women rooters at the Polo Grounds, from the grandstand to get Matty to come out and get ready to pitch. Myers [sic] is the first to answer the call for assistance, and when he comes out of the clubhouse door with his uniform on carrying his mask and protector and shin guards, the fans in the audience almost raise the roof. Myers explains that Matty is playing checkers and can’t be disturbed, but a moment later, ‘Big Six,’ ball in hand, shows himself, and the audience is off again. Later Mr. Mathewson, pitching to Mr. Myers, shows Miss Tully how to shoot over the different sort of curves. This little lesson is interrupted by Myers leaving the scene long enough to get into the game as a pinch hitter, and he goes off right to rap out a home run. Then he and Matty retire to the clubhouse to dress, and while they are gone Miss Tully springs some imitations of well-known actors and actresses at a ball game, which are remarkably clever and entertaining.31

Mathewson and Meyers then return to the stage in their street clothes, and Tully returns the favor by convincing Mathewson and Meyers to join her in vaudeville and by teaching them to act. This “brings out a travesty drama with Meyers as the ‘bad Indian’ … Mathewson is the cowboy who comes to the rescue of the forlorn maiden and over comes the ‘bad Indian’ by hitting him in the head with a baseball.”32

Meyers naturally felt silly in this role himself, although he enjoyed the experience otherwise. At the time, though, newspaper reviews of the performance were complimentary. After its debut at Hammerstein’s Victoria in New York on October 23, 1910, the reviewer for Variety wrote: “A most satisfactory vehicle … a little cutting is all the piece needs.”33

The act toured the vaudeville circuit for several weeks. Meyers was amenable to other stage offers later, but did not receive any. Mathewson never appeared on stage again, apparently sensitive to criticism of his performance.

For each of the next three seasons, Meyers finished in the Top 10 in Chalmers Award voting for the National League’s most valuable player. In 1911 he led the Giants in batting for the first of three consecutive seasons with a .332 average, third highest in the National League. “Meyers has become the deepest student of batting on the team,” wrote a New York Times reporter after watching him correctly predict the pitches thrown by Pirates phenom Marty O’Toole.34 The next year Meyers hit for the cycle on June 10 en route to a career-high 6 home runs and a .358 average, second in the NL behind only Heinie Zimmerman’s .372. His hot hitting continued in the 1912 World Series, when he started all eight games and batted .357/.419/.429. Meyers remained one of the Giants’ best hitters through the 1914 season, when he batted .286/.357/.354 in a career-high 134 games.

The workload took its toll. “I cheated a little on my age so they always thought I was a few years younger,” Meyers recalled, “but when the years started to creep up on me I knew how old I was, even if nobody else did.”35 Playing in over 100 games for the sixth consecutive season, the 34-year-old Meyers batted just .232/.311/.311 in 1915, and the Giants placed him on waivers. Both the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Braves claimed him, and Brooklyn won his rights on a coin flip. In Brooklyn Meyers was reunited with ex-Giants Rube Marquard, Fred Merkle, and his catching mentor, Wilbert Robinson, now his manager. He remembered the 1916 Robins as “just outsmarting the whole National League” on their way to the pennant but running out of gas in the World Series against the Boston Red Sox.36

Meyers split the 1917 season between the Dodgers and Braves, on the latter club replacing Hank Gowdy, the first active major leaguer to enlist for service in World War I.

In 1918 Meyers joined the Buffalo Bisons, managed by his former Giants teammate Hooks Wiltse,37 and batted .328 in 65 games. After the war-shortened 1918 season, Meyers enlisted in the US Marine Corps himself. The war ended before he could be deployed, and he received an honorable discharge on March 17, 1919.38 He returned to baseball as player-manager for New Haven in the Eastern League but was replaced in midseason by Danny Murphy, whom he had played against in the 1911 World Series. Meyers was catching for a semipro team in San Diego in 1920 when the crowd booed him and he decided to quit baseball altogether.39

As gregarious as Meyers was, and as freely as he could tell tales about himself (however fanciful they might be), he said little publicly about his family or personal life. Almost nothing is known of his marriage to Anna Meyers, other than that the couple lived in a home with an apple orchard in New Canaan, Connecticut,40 and the marriage ended at some point without producing children.

Meyers invested his earnings prudently, but the stock market crash of 1929 wiped out his savings. In a 1961 interview, he told this story:

I had a Lincoln automobile. I traded it for a Ford and struck out for California – home to me. I went back to the reservation and slept out under a big pine tree. It was a far different life than I had known – pampered by masseurs and the easy life in the country’s best hotels. The ground was hard.

On the third morning, I woke up and told myself a few facts. “You’re not the only Indian that went broke,” I said. “Get up and go to work.” I went to Riverside and at the Mission Indian Agency, asked if they had a job I could do. They told me I was just the man they were looking for. They needed an agent to direct law enforcement on the Indian reservations of Southern California, some 30 in all. I stayed on that job until I retired at 65.41

The picturesque tale telescopes several details but appears true in essentials. Meyers was actually already in Southern California, working as a construction foreman for the San Diego gas company, when the crash occurred. He lost his job due to cutbacks in 1931, and held several other jobs before his appointment as chief of police for the Mission Indian Agency of Southern California in 1933.42 “You see,” he told a reporter, “that really makes me a chief now. I’m entitled to the name.”43

His nephew, Jack Meyers, remembered his namesake performing “Casey at the Bat” for children’s groups around the Santa Rosa reservation. “He could be very theatrical and entertaining,” recalled his nephew. Meyers was a favorite at old-timers’ games for both the Dodgers and the Giants for many years, especially after those teams moved to California. He was also a favorite of sportswriters looking for reminiscences of the game’s earlier days, and told many colorful stories (often with an implied wink and nod) to new audiences throughout the years.

William A. Young, Meyers’ biographer, emphasizes that Meyers’s story “must be seen within the context of the struggles of Native Americans in general, and athletes in particular, to maintain their dignity and self-respect. … Though it was not an easy passage, he did successfully negotiate the treacherous boundaries between the Native American and Euroamerican worlds. Though he entered the white man’s world willingly and was able to compete on its playing fields, according to its rules, he was also intensely proud of his Native American identity and heritage. Throughout his life he drew on the Cahuilla values he learned as a child.”44

Meyers died on July 25, 1971, in San Bernardino, California, just four days before his 91st birthday.45

Sources

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s Deadball Stars of the National League (Brassey’s, Inc., 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Photo credit: John Tortes Meyers, Library of Congress.

Notes

1 “How Chief Meyers Broke into Game,” Washington Post, April 15, 1909: 3.

2 William A. Young, John Tortes “Chief” Meyers: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 23.

3 Young, 10. It should be noted that a genealogy on Ancestry.com gives John Mayer’s year of death as 1911. Mayer’s 1910 census entry gives his birthplace as Germany and his immigration year as 1868.

4 Young, 9.

5 Earl E. Buie, “They Tell Me,” San Bernardino (California) Sun-Telegram, April 5, 1961, 14.

6 Young, 17.

7 Henry C. Koerper, “The Catcher Was a Cahuilla: A Remembrance of John Tortes Meyers (1880-1971), Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. Vol. 24, No. 1 (2004): 21-40.

8 Koerper, 24.

9 A copy of the diploma may be found in Meyers’ National Baseball Hall of Fame Library file.

10 Koerper, 25.

11 Koerper, 25.

12 Jim McGreal, “Ralph Glaze: They Called Him ‘Pitcher,’” Baseball Research Journal (SABR), 1986: 79.

13 “How Chief Meyers Broke into Game.”

14 “How Chief Meyers Broke into Game.”

15 “How Chief Meyers Broke into Game.” Neither the box score of the game in the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Daily Independent, July 5, 1906: 5, nor the game story charges any passed balls to Meyers, but he is charged with one throwing error that resulted in a run. A blurb adds: “Meyers started to catch the game, but he was not used to Leary’s ‘spit balls,’ and retired at the end of the first inning.”

16 “Catcher Meyers Released,” Harrisburg Daily Independent, July 11, 1906: 2.

17 “Bits for the Fans,” Harrisburg Telegraph, July 12, 1906: 8.

18 “Lancaster 5; Williamsport 4,” Harrisburg Daily Independent, July 23, 1906: 8.

19 Koerper, 26. The president of the Butte club, Charles H. Lane, was a prominent Butte coal dealer and eventual mayor of Butte from 1915 to 1917. Lane’s business interests were probably closely tied to Anaconda Copper, a dominant employer in Butte. See https://archive.org/stream/montanaitsstoryb02stou/montanaitsstoryb02stou_djvu.txt (as of February 6, 2025) for a biography of Charles H. Lane.

20 “Chit-Chat of the Diamond,” Anaconda Standard, May 3, 1907: 2.

21 Carlos Bauer, The Obscure History of Baseball in San Diego: Before the Padres Came to Town, 1870-1936 (San Diego: Baseball Press Books, 2024), 49.

22 “Association Batting Averages,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, June 28, 1908: 39. Meyers finished with a .292 average.

23 “Paid $17,000 for Pitcher and Catcher,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 02, 1908: 10.

24 “Giants Please Home Fans,” Washington Post, April 11, 1909: S2.

25 “30,000 See Giants Lose to Superbas,” New York Times, April 16, 1909: 7. The Giants, however, could not score and lost, 3-0.

26 “$17,500 [sic] Battery Defeats Phillies,” New York Times, April 18, 1909: S1.

27 R.W. Lardner, “Heap Big Indian Scalps Bear Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1909: 8.

28 John Lenkey, “Chief Meyers Hale and Hearty at 86,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1967: 29.

29 Irvin S. Cobb, “Irwin [sic] Cobb Tells of the Giants Victory,” Buffalo Times, October 26, 1911: 14.

30 “$2,000 For Baseball Act,” Variety, September 24, 1910: 4. The article reports both figures.

31 Dash, “Curves,” Variety, October 29, 1910: 16.

32 Dash, 16.

33 Dash, 16

34 “Giants Confident, Pirates Hopeful,” New York Times, September 18, 1911: 9.

35 Lawrence Ritter, ed., The Glory of Their Times: The Enlarged Edition (New York: William Morrow, 1992), 179.

36 Ritter, 179.

37 “Bison Players Signed for 1918; Open Here May 17,” Buffalo Enquirer, April 20, 1918: 10.

38 Young, 182-184.

39 Steve George, “Chief Meyers, Unrecognized and Almost Forgotten, Emerges from Out of Game’s Early Memory Book,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1936, 9.

40 Meyers’ World War I draft registration card lists his address as New Canaan, and his occupation as “farmer.”

41 Buie.

42 Koerper, 42.

43 George.

44 Young, 7.

45 “Ex-Big League Great, Chief Meyers, Dies,” San Bernardino County Sun, July 27, 1971: D1.

Full Name

John Tortes Meyers

Born

July 29, 1880 at Riverside, CA (USA)

Died

July 25, 1971 at San Bernardino, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.