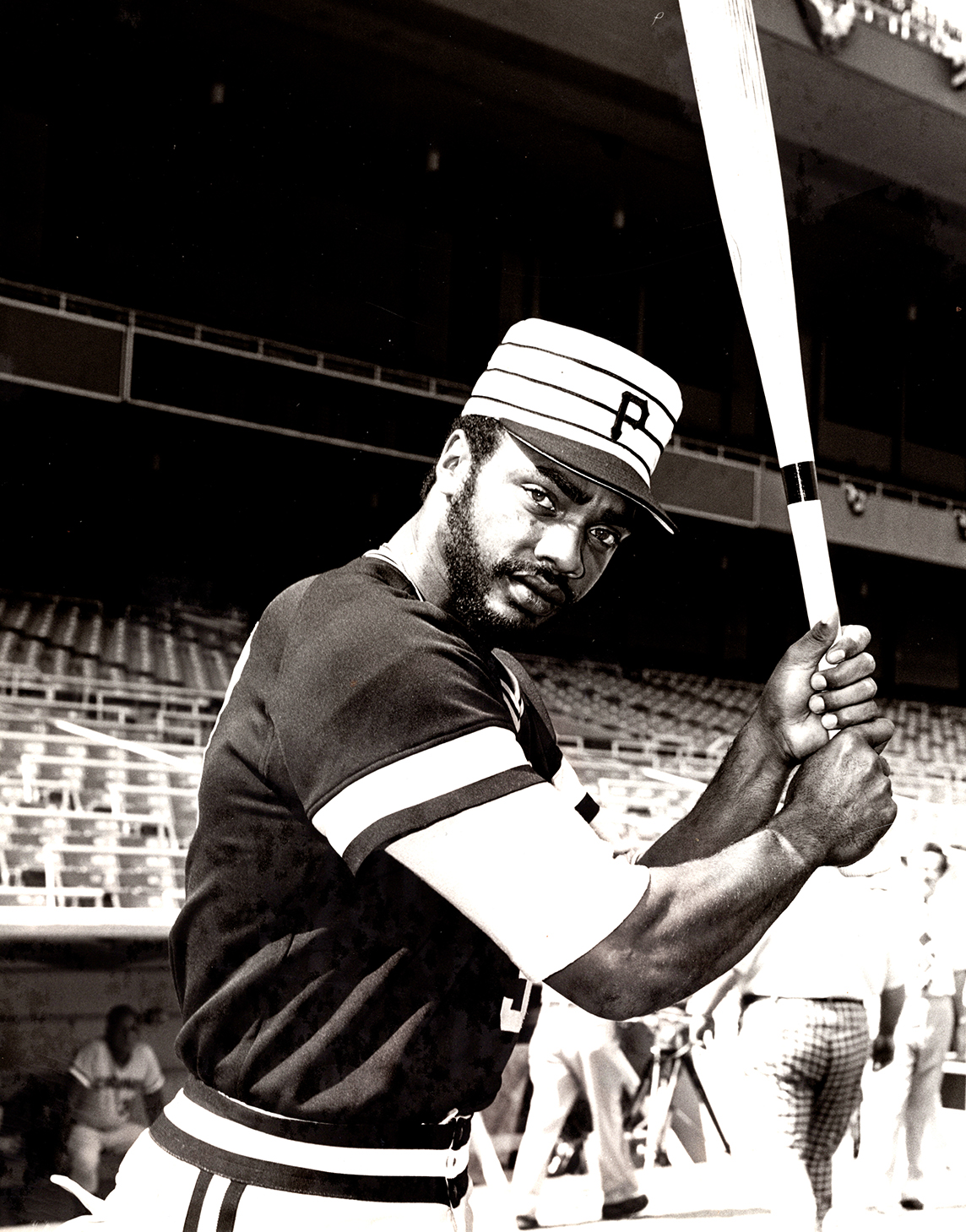

Dave Parker

How you remember Dave Parker depends largely on what you remember him for.

How you remember Dave Parker depends largely on what you remember him for.

Do you remember him as one of the best players in the major leagues in the last half of the 1970s? The man who was the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1978 and MVP of the All-Star Game in 1979? The man who played a key role on the Pittsburgh Pirates’ 1979 World Series champions?

Or do you remember him as the overweight, injury-prone drug user who was the target of anger and resentment from Pittsburgh fans in the early 1980s when his production dropped off after he signed what was at the time the most lucrative contract in baseball history? The man who testified at a high-profile 1985 trial in federal court about his cocaine use and as a result was sued by the Pirates for fraud?

Parker’s final totals after 19 seasons in the big leagues are impressive: 339 home runs, 1,493 RBIs, 2,712 hits, and a .290 batting average. He finished in the top five in the MVP voting five times (and got votes in four other seasons), played in six All-Star Games and was on the roster for another (and wasn’t selected for the game in his MVP year due to injury) and was a regular in the lineup for two World Series winners.

It was a resume similar to that of Jim Rice, Parker’s American League counterpart for MVP honors in 1978. But while Rice was elected to the Hall of Fame by the baseball writers, Parker never received as much as 25 percent of the vote in his 15 years on the writers’ ballot, perhaps because the memories of the cocaine years and the perception of squandered talent were too much for some voters to overcome.

After failing to reach 75 percent of the vote from three different veterans committees, Parker was finally elected to the Hall of Fame by the Classic Era Committee in December 2024. But he died at the age of 74 just one month before the induction ceremony in the summer of 2025.

David Gene Parker was a big man with a big personality. (“There’s only one thing bigger than me, and that’s my ego,” Parker told Sports Illustrated in 1979.1) He grew to be 6-feet-5 and was listed in his younger days at 225 pounds, although he was considerably heavier in the early 1980s. He was big from the beginning, weighing 11 pounds 14 ounces when he was born on June 9, 1951, in Grenada, Mississippi, one of six children of Richard and Dannie Mae Parker.2

Both parents were athletic. “My mother had a cannon for an arm,” Parker said. “My dad never got to play organized ball. But he’d crush that ball. And he could run like a scalded rabbit. He beat me in a footrace one day after work – in his workboots, carrying his lunch bucket.”3

In 1956 the Parkers moved to Cincinnati, where Richard worked at Lunkenheimer Valve Company and Dannie Mae worked as a maid. The family settled on Poplar Street, a short walk from Crosley Field, home of the Cincinnati Reds. Parker made that walk frequently in his youth. “Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson would come out and there I’d be, waiting for them,” Parker remembered. “And, believe it or not, they were always nice to me. They’d come out and give me a glove or a ball.” As a teenager Parker worked as a vendor at the ballpark.4

Parker attended Courter Technical High School, where he was a standout in football, basketball, and baseball.5 “Football was my first love,” Parker confessed. “I loved it because it’s a contact game. I liked to run over people.”6 As a junior in 1968 Parker earned first team all-Public High School League honors as a running back.7 More than 60 college football programs, including many of the major powers of the day, contacted him. But an injury to his left knee in the first quarter of the first game of his high-school senior year in 1969 ended his dream of playing college football. He underwent surgery the day after Thanksgiving and sat out his senior season of baseball.8

As a junior Parker had led his Courter Tech team in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in.9 His primary position was catcher, but he also did some pitching. And he played some outfield for a Cincinnati team sponsored by Wilson Freight that appeared in the Connie Mack World Series in August 1969.10

Parker was on the radar of major-league scouts. Harding “Pete” Peterson, then the Pirates scouting director, first saw him at a tryout camp in Columbus, Ohio, before the June 1970 amateur draft. “He was one of 10 or 12 players we were looking at,” Peterson recalled. “I didn’t think he was the best of the group. I liked an outfielder named Bill Flowers. Remember him?” (Flowers was a Courter Tech classmate of Parker. Cleveland selected Flowers in the second round of the June 1970 draft and he played eight seasons in the minors but never got beyond Triple-A.)

The Pirates drafted Parker in the 14th round, making him the 332nd player chosen.11 Parker insisted he “would have been picked in the first or second round” had it not been for the knee injury,12 but others disagreed; Sports Illustrated wrote in 1979: “Actually, say Peterson [then the Pirates’ executive vice president] and scout Howie Haak, Parker, who then seemed incapable of hitting a ball in the air, just didn’t look like all that much of a prospect. Furthermore, because he had a history of wrangling with coaches, he was dismissed by some scouts as a ‘militant.’ ‘The Reds had been watching him all along,’ says Haak. ‘They laughed at us when we took him.’”13

Parker was listed as a catcher-outfielder on The Sporting News’ list of draftees,14 but that changed when Parker joined the Pirates’ rookie league team in Bradenton, Florida. “The first day I reported, I was told to find a fielder’s glove,” he said. “That was the end of my career as a catcher.”15

Playing the outfield for the Pirates’ team in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League in 1970, Parker tied for the league lead in home runs and total bases and was named the league’s most valuable player.16 “That’s when I realized I could do it,” he said. “I was a 14th-round draft choice, but when I got with other kids from all over the United States and some foreign countries and stood out, I realized I must be pretty good.”17

The Pirates were impressed enough to promote Parker – still only 19 years old – all the way to Double-A to start the 1971 season. But Parker struggled with Waterbury (Connecticut) in the Eastern League, hitting just .228 with no homers in 30 games before being demoted. “I was the youngest guy there and I tried too hard to prove myself,” he said.18

After being sent to Monroe (North Carolina) of the Class-A Western Carolinas League, Parker re-established himself as a top prospect, batting .358.19 Then in 1972 he earned player-of-the-year honors at Salem (Virginia) in the Class A-Carolina League, leading the league in batting average, RBIs, runs scored, hits, doubles, stolen bases, outfield putouts, and outfield assists while missing the home run title by one.

In 1973 the Pirates promoted Parker to Charleston (West Virginia) of the Triple-A International League, where he got off to a blazing start. On July 10 Pirates outfielder Gene Clines tore ligaments in his right ankle going into second base in San Diego.20 Parker, who was leading the International League with a .317 batting average, was called up to replace him, and on July 12 – barely a month past his 22nd birthday – he made his major-league debut as the Pirates’ right fielder and leadoff hitter. (Parker’s first three starts came in the leadoff spot; he never hit in that position in the order again in any of his 2,331 subsequent starts.)

Parker hit .354 in September to finish the season with a .288 mark. But the left-handed hitter was used strictly as a platoon player; all of his 31 starts came against right-handed pitchers and he had just 10 plate appearances against lefties. In 1974 Parker was on the disabled list most of June and July with a hamstring injury. He finished the year with a .282 batting average but just four home runs in 220 at-bats, and again he saw limited action against lefties (three starts and 27 plate appearances).

But in 1975 Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh took the platoon restriction off Parker and, given the chance to play every day, Parker became a star. Over the next five seasons (1975-79) his batting average was .308 or better every year and he averaged 23 home runs, 98 RBIs, 95 runs scored, and 17 stolen bases per season. (He also proved Murtaugh was right to stop platooning him; Parker hit .300 or better against lefties for four straight years, 1976-79, and actually had a better batting average against left-handers than right-handers in 1976 and 1977.)

During that five-year span Parker led the National League in batting average twice (.338 in 1977 and .334 in 1978) and slugging percentage twice (1975 and 1978), was named to The Sporting News’ postseason National League all-star team three times (1975, 1977, 1978) and won three Gold Glove awards for fielding excellence (1977-79). In 1977 he had 26 assists, still (through 2025) the most for any major-league outfielder in a season since another Pirate right fielder, Roberto Clemente, had 27 in 1961.21

During that five-year span Parker led the National League in batting average twice (.338 in 1977 and .334 in 1978) and slugging percentage twice (1975 and 1978), was named to The Sporting News’ postseason National League all-star team three times (1975, 1977, 1978) and won three Gold Glove awards for fielding excellence (1977-79). In 1977 he had 26 assists, still (through 2025) the most for any major-league outfielder in a season since another Pirate right fielder, Roberto Clemente, had 27 in 1961.21

Widely known by his nickname, “Cobra,” given to him early in his Pirates career by team trainer Tony Bartirome,22 Parker was a loud and lively presence in what was the loudest and liveliest clubhouse in the major leagues. “If you first meet me in the clubhouse, you’d say I’m very insulting,” he noted. “Loud. Maybe you’d even think in terms of a bully.”23 But his taunts had a purpose. “I’m a motivator. I’ll point out guys’ faults. I’ll tell a guy he’s pulling out, that he couldn’t hit a balloon. He thinks to himself, ‘I’ll show that turkey.’ It makes him better.”24

Phil Garner, Parker’s teammate from 1977 to 1981, agreed. “If you feel down, sorry for yourself, he gets the spark going in you. Dave’s found that picking on someone makes guys rally round, laugh. Suddenly, they’re ready. It’s group therapy.”25

“It didn’t matter where you were born, your ethnic heritage, religious background, marital status,” said Jerry Reuss, a teammate of Parker’s from 1974 to 1978. “Dave was an equal-opportunity offender. Nothing was sacred. Nor was it personal. But it was a daily comedy routine.”26

On June 30, 1978, at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, Parker attempted to score the tying run in the bottom of the ninth after Bill Robinson flied out to right field. Parker dived head-first into Mets catcher John Stearns, a former college football player, who was knocked on his back but held onto Joel Youngblood’s throw to retire Parker and end the game.27 “That was like the Pennsylvania Railroad colliding with the B&O,” Pirates manager Chuck Tanner said afterward.28

Parker took three stitches over his left eyelid after the game. The next day his eye was swollen nearly shut, and it was determined that he had fractured his left cheekbone, but he agitated Tanner to put him in the lineup anyway. “I’m the toughest man in the world,” he insisted two days after the injury. “I can see, so I can play.”

“If I put his name in the lineup, I’m sure he’d play. But there’s no way,” Tanner responded. “There isn’t a player alive who plays the game the way Dave Parker does. Every game is the seventh game of the World Series to him. There isn’t a player alive who can do the things on the field that Parker can do. None.”29

Parker went on the disabled list (and as a result was not selected to play in the All-Star Game), and when he returned to action July 16 he was wearing a hockey goalie mask to protect his face. Because he had trouble seeing some pitches wearing the mask, he went back to wearing a conventional batting helmet at the plate, but when he reached base he would switch to a batting helmet with a football facemask attached that he continued wearing into the 1979 season.30

Parker struggled at the plate when he came back from the injury, at one point going into an 0-for-24 slump. But he rallied to play the best baseball of his career down the stretch, batting .381 in August and .412 after September 1 to win National League Player of the Month honors in consecutive months. He finished the season with a major-league-best .334 batting average plus 30 home runs and 117 RBIs while leading the league in total bases, despite missing 13 games due to the injury. He won Most Valuable Player honors, receiving 21 of the 24 first-place votes.

After the 1976 season Parker signed a three-year contract calling for salaries of $175,000 in 1977, $200,000 in 1978, and $225,000 in 1979. He almost immediately regretted it, as he saw other players get bigger deals. “Putting my salary up against them is putting me up against guys who couldn’t carry my bat to the plate,” he said. “I feel I’m one of the best talents in baseball and I want to be paid like one of the best.”31 After his MVP season in 1978, Parker and his agent, Tom Reich, began negotiating a new long-term contract with the Pirates, with the threat that Parker might leave as a free agent when his existing contract expired at the end of the 1979 season.32 There were reports that Parker was asking for $1 million a year – something no baseball player had ever received.33

On January 26, 1979, the Pirates announced they had signed Parker to a five-year contract that would begin in 1979 (replacing his existing agreement). While the terms aside from the length were not disclosed, it was immediately, and for years afterward, referred to as baseball’s first million-dollar-a-year contract.34 But while the contract was designed to pay Parker at least $7.75 million, the money would be paid out over 30 years, and he would not receive $1 million in any year he played.

His base salary was a mere $300,000 a year for each of the five seasons (1979-83). There was also a $325,000 bonus when the contract was approved and another $300,000 in 1980. Most of the money would come in deferred payments, beginning with a $1 million lump sum in January 1988, followed by 222 monthly payments of $20,833.33 each (a rate of $250,000 a year) beginning in January 1989. The contract also included a number of incentive bonuses, for which Parker eventually received $65,000.35

It was a contract that changed the way fans looked at Parker and would come to haunt him over the next five years. “I think it took away from people looking at me as Dave Parker, hustling ballplayer, and turned it into Dave Parker, million-dollar man.”36 And Parker found that that dollar figure was something Pittsburgh fans couldn’t relate to. “Basically this is a coal-mining, steel-melting city,” he said. “These people work hard for their money and it’s hard for them to imagine making this type of money playing games.”37

Parker was named the most valuable player in the 1979 All-Star Game at Seattle’s Kingdome, not for his bat but for his arm. In the seventh inning, with the AL leading 6-5, Parker overran leadoff hitter Jim Rice’s shallow fly ball, went back into the right-field corner to retrieve it after a high bounce, and retired Rice trying to advance to third base with a one-hop throw. Then in the eighth, with the game tied 6-6, Parker fielded Graig Nettles’ hit in deep right field and threw home. The ball reached catcher Gary Carter shoulder-high on the fly, and Carter tagged out Brian Downing trying to score the go-ahead run.38 The National League scored in the ninth and held on to win 7-6.

With Parker and 39-year-old first baseman Willie Stargell, the National League’s co-Most Valuable Player, leading the way, the 1979 Pirates won 98 games and the National League East championship, after which they defeated the Cincinnati Reds in the National League Championship Series and the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Parker hit .365 in September and .341 in 10 postseason games, even though he was troubled by his left knee that was injured swinging at a pitch in late August, making it painful for him to try to pull the ball.39 His 10th-inning single drove in the winning run in Game Two of the NLCS, and he was also credited with the game-winning RBI in Game Three of the NLCS and Game Six of the World Series.

Parker had what for any other player would have been considered an outstanding season. He finished second in the National League in total bases, third in doubles and tied for third in runs scored; ranked in the top 10 in batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage; and won his third straight Gold Glove. But his batting average was “only” .310, more than 20 points below his league-leading marks of 1977 and ’78, and his 94 RBIs were well short of the 117 he had the previous year. Some Pittsburgh fans felt that they should have gotten more in the wake of the big contract. “They said for a million dollars that was a bad year,” Parker said. “The pressure was there, without a doubt.”40

Things between Parker and Pittsburgh fans were so bad that he skipped the victory parade after the 1979 World Series. “Why should I? Where were they when I needed them?” Parker said.41 And things would get much worse over the final four years of his contract.

The lowlight of 1980 came on July 20 when someone at Three Rivers Stadium threw a 9-volt battery at Parker while he was standing in right field during the first game of a doubleheader against the Dodgers. Parker immediately removed himself from the game and did not play the field in the second game. “I could hear it go by me,” he said afterward. “It was too close for comfort. I wasn’t going to stand there and give him another shot.”42 The next day, saying the battery incident was the “fourth or fifth” time he had been the target of a thrown object,43 Parker asked to be traded, saying he had “reached the point of no return” with Pittsburgh fans.44

There were off-field problems in 1980 as well. A landscaper took him to court, claiming Parker owed $9,000 for work done on his home, and Pittsburgh National Bank sued him over missed payments on an $11,097 loan, neither of which Pittsburgh fans found appropriate for someone they thought was making $1 million a year.45 And his common-law wife, Stella Miller Parker, sued for divorce, accusing him of adultery and “cruel and barbarous treatment.”46

On the field, Parker’s 1980 season was good enough – a .295 batting average, 17 home runs, and 79 RBIs – but in the context of his salary it seemed a big disappointment. He was limited to 139 games because of injuries that kept him from playing at full speed in many of the games he did play. In September New York Times reporter Jane Gross wrote that Parker’s left knee was “so sore that he limped to the plate, looked like a lame horse on the base paths, and was forced to play deeper than usual in the field because he had trouble going back for the ball.”47

“He plays a lot of times when he can hardly walk into the clubhouse,” manager Chuck Tanner told Gross. “Every time I take him out of the lineup because he’s hurting, he says he wants to play and I play him every time he asks.”48

Parker had cartilage removed from his left knee after the season and recovered in time to start the 1981 campaign. But in a season that was interrupted by a nearly two-month players strike, he played just 67 games. He spent two weeks on the disabled list in May with a slight tear in his right Achilles tendon,49 then missed time in late August and September with a painful thumb injury.50 His batting average dropped to .258 and he hit only nine home runs, and his once-feared arm produced just one assist.

Parker’s weight also became an issue. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette beat writer Charley Feeney wrote that it “might have gone higher than 260, but Parker insists [it] was never more than 245.”51 Either was well above what was considered Parker’s normal playing weight of 230, and the extra weight wasn’t doing his knees any good. “For the money Dave Parker makes,” Sporting News columnist Bill Conlin wrote, “he owes Chuck Tanner, his teammates and Pirates fans more than first prize in a Goodyear blimp look-alike contest.”52

Those Pirates fans were completely disenchanted with their “million-dollar-a-year” star. “How popular is Dave Parker in Pittsburgh?” Feeney wrote. “Let’s put it this way: if Parker ran for mayor unopposed, he’d lose in a landslide.”53

Somehow 1982 turned out even worse for Parker than 1981. He was out nearly six weeks in May and June with torn cartilage in his right wrist and spent another six weeks on the disabled list from late July until early September after he ruptured a ligament in his left thumb in a head-first slide.54 He wound up playing only 73 games, with just six home runs.

Parker stayed off the disabled list in 1983 (although he later said he had a problem with his Achilles tendon all season55) and played 144 games. He went into the All-Star break with a .242 batting average and only three home runs, but the 32-year-old suddenly showed flashes of his old self in the second half, dropping his weight to 225 and hitting .305 with nine homers and 48 RBIs. Pirates fans forgave him enough to give him several standing ovations.56 The comeback came at an opportune time, with Parker entering free agency for the first time after the season.

At that time free agents were subject to what was known as the “re-entry draft,” in which teams drafted the right to negotiate with the player. There were no limits on the number of players a team could draft or on the number of teams that could draft a player. Dave Parker, former MVP and two-time batting champ, was drafted by only two teams: Seattle and his hometown Cincinnati Reds.57

And home was where Parker decided to go, in a move that reinvigorated his career. He signed a two-year contract with the Reds and celebrated his return to Cincinnati by marrying Kellye Crockett on Valentine’s Day 1984.58

In 1984 Parker drove in 94 runs, his most since the Pirates’ 1979 championship season, and hit .285. The Reds rewarded him with a three-year contract extension, and Parker rewarded them with one of his best seasons in 1985. He hit .312, his 34 home runs and 125 RBIs were career highs, he led the league in RBIs, total bases, and doubles, and he ranked second in hits and homers. He finished second in the Most Valuable Player voting to Willie McGee, who hit a league-leading .353 for the National League champion Cardinals.

The day before the 1985 All-Star Game, Parker won the first All-Star Home Run Derby, hitting six home runs at the Metrodome in Minneapolis. The event was organized as a team competition, and Parker’s National League team lost to the American League team, 17-16.59

But Parker’s on-field performance in 1985 was overshadowed by his testimony in a federal court drug trial in Pittsburgh in September. Granted immunity in exchange for his testimony against a man charged with distributing cocaine to professional baseball players, Parker said he first used cocaine while playing winter baseball in Venezuela in 1976 and had used the drug “with consistency” from 1979 until he quit late in the 1982 season because “my game was slipping. I felt it played a part in it.”60 He also named several other major-league players who he said had used the drug.

While Parker could not face criminal prosecution, his admission had financial consequences. On February 28, 1986, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth suspended Parker and six other players who had used cocaine and “in some fashion facilitated the distribution of drugs in baseball.” The one-year suspensions were waived when the players agreed to contribute 10 percent of their 1986 salaries to programs to combat drug abuse, submit to drug tests for the rest of their careers, contribute up to 200 hours of community service and participate in antidrug programs established by baseball.61

Then in April the Pirates – under new ownership since Parker had played for them – sued Parker in an attempt to get out of making the more than $5 million in deferred payments called for under his 1979 contract. “He was using cocaine,” Pirates president Malcolm Prine said. “That negatively affected his ability to perform. The Pittsburgh Pirates were deprived of that which he promised to provide.”62 The Pirates also claimed that Parker “failed to keep himself in good physical condition” under the terms of the uniform players’ contract, “with his weight ballooning at times to in excess of 270 pounds, as a result of which he became injury-prone.” (“That 270 pounds is in no medical records,” Parker responded. “I’d like to see them prove that.”)63

Parker and the Pirates reached a settlement in December 1988.64 Terms were not announced, but Carl Barger, who was then the team president, said the team would pay “significantly less” than what was owed under the contract.65

Parker had another fine year for the Reds in 1986, playing every game and finishing fifth in the MVP voting. He led the league in total bases while hitting 31 homers and driving in 116 runs. In 1987 he drove in 97 runs, but his batting average dropped to a career low .253 (just .228 after the All-Star break), and after the season the Reds traded the 36-year-old to the Oakland Athletics for young pitchers José Rijo and Tim Birtsas.

Parker was in the A’s 1988 lineup almost every day, either in left field or as the designated hitter, until he strained ligaments in his right thumb sliding into second base on July 3.66 He returned to action in late August and was the regular DH after that, helping the A’s win the American League pennant. He finished the year with modest numbers: a .257 batting average, 12 homers, and 55 RBIs in 101 games.

In 1989 Parker was used almost exclusively as a DH, and his bat helped the A’s repeat as American League champions and sweep the San Francisco Giants in the earthquake-interrupted World Series. He led the team with 97 RBIs during the regular season and won the league’s Designated Hitter of the Year award, then hit his first postseason home runs, two against Toronto in the American League Championship Series and one in Game One of the World Series. In the process Parker earned the respect of his teammates. “It’s unbelievable how hard he works,” Mark McGwire said. “He just lifts the whole ballclub up by his attitude. He is so well liked by everybody.”67

The World Series marked the end of Parker’s tenure in Oakland. He was a free agent after the season, and with the A’s deciding not to offer a multi-year contract, he signed a two-year contract with Milwaukee.68 He repeated as Designated Hitter of the Year with the Brewers, hitting .289 in 1990 with 21 homers and 92 RBIs. But the Brewers decided to get younger after the season, trading the 39-year-old Parker to the California Angels for 27-year-old outfielder Dante Bichette.

Parker struggled with the Angels in 1991, hitting just .232 with 11 homers in 119 games, and was released on September 7. A week later he was picked up by Toronto and hit .333 in 13 games to help the Blue Jays win the American League East, but because he joined the team after September 1 he was ineligible to play in the postseason.

While Parker was with the Angels, his teammate Dave Winfield encouraged him to consider buying fast-food franchises as a financial investment.69 Parker and his wife bought a Popeye’s fried-chicken franchise in Cincinnati, where they continued to make their home, and when he had no offers to continue his major-league playing career in 1992, Parker went home to help Kellye run the business and play in a local baseball league for men 35 and older.70

Parker got back into a major-league uniform in 1997, when Angels manager Terry Collins (who had been the second baseman on Parker’s Carolina League team in 1972) hired him as first-base coach. “I really came back out just to be visible,” said Parker, “and I actually fell in love with coaching.”71 In 1998, given the chance to work for Tony La Russa, his manager in Oakland, and become a hitting coach, Parker joined the St. Louis Cardinals coaching staff. But after that season Parker went home to Cincinnati.

In August 2013 Parker revealed to Joe Starkey of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in February 2012.72 Dave and Kellye sold their restaurants and started the Dave Parker 39 Foundation (39 being the uniform number Parker wore throughout his major-league career), “a non-profit organization focused on finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease in our lifetime, and to make life better for those living with the disease today.”73

Parker returned to Pittsburgh for the 40th anniversary reunion of the 1979 World Series champions and he received a standing ovation from Pirates fans at PNC Park. He was inducted into the Pirates’ team hall of fame in 2022.

Parker died on June 28, 2025, after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. He will be posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on July 27 in Cooperstown, New York.

In the most recent edition of his Historical Baseball Abstract, published in 2003, Bill James ranked Parker the 14th best right fielder in baseball history.74 All 13 players ranked ahead of him were in the Hall of Fame. Now, so is the Cobra.

Last revised: June 28, 2025

Sources

Special thanks to Michael Haupert, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, for providing a copy of Parker’s official contract card, and to Bill Van Niekerken, library director for the San Francisco Chronicle, for providing articles from the Chronicle’s archive that are not available online.

David L. Snyder’s article in the January 2012 Albany (New York) Government Law Review, “The Cobra’s Contract: Revisiting Dave Parker’s 1979 Contract With the Pittsburgh Pirates,” is a comprehensive and fascinating look at the negotiations leading to Parker’s historic contract with the Pirates and the team’s lawsuit to dispute his deferred payments. The article is online at http://albanygovernmentlawreview.org/Articles/Vol05_1/5.1.188-Snyder.pdf.

Two good sources for information about the Pittsburgh cocaine trial of 1985 are Aaron Skirboll’s book The Pittsburgh Cocaine Seven: How a Ragtag Group of Fans Took the Fall for Major League Baseball (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2010) and Steve Beitler’s article “This Is Your Sport on Cocaine: The Pittsburgh Trials of 1985,” published in the Society for American Baseball Research’s The National Pastime #26 in 2006.

Photo credits: Dave Parker, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Notes

1 Roy Blount, “A Loudmouth and His Loud Bat,” Sports Illustrated, April 9, 1979.

2 Birth weight from Bernie Lincicome, “New Uniform Suits Parker Just Fine,” Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1984: section 4, 1.

3 John Erardi, “Dave Parker a Hall of Fame Presence,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 6, 2014, http://cincinnati.com/story/sports/columnists/john-erardi/2014/08/06/erardi-dave-parker-hall-fame-presence/13697129/.

4 Bob Hertzel, “From Crosley to the Majors,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 15, 1973: 49.

5 Courter Tech shut down in 1974. Its former campus is now the home of Cincinnati State Technical and Community College, more commonly known as Cincinnati State. http://cincinnatistate.edu/about-cs/cincinnati-state-histor.

6 Charley Feeney, “On Playground or Battlefield, Parker Is BIG,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1977: 3.

7 “Campbell Honored By PHSL,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 20, 1968: 24. Parker’s exact statistics for the season are in question. In 1973, Bob Hertzel wrote in the Cincinnati Enquirer that Parker had 1,365 yards rushing in 10 games, a figure that was repeated in numerous other stories over the years. But when Parker was inducted to the Cincinnati Public Schools Hall of Fame in 2012, that organization said he “rushed for over 1,110 yards” and scored 68 points. That document is online at http://cps-k12.org/files/pdfs/Athl-HOF-12.pdf.

8 “Courter Is Minus Parker,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 18, 1969: 44. Parker actually did return to the football team before the season was over and was named second team all-PHSL before undergoing the operation.

9 http://cps-k12.org/files/pdfs/Athl-HOF-12.pdf.

10 “CM World Series Rosters,” Farmington (New Mexico) Daily Times, August 15, 1969: 6. Other future major leaguers who played in the tournament included Rick Burleson, Steve Staggs, Mike Proly, Eric Raich, Tommy Bianco, Bob Kammeyer and Parker’s Wilson Freight teammate Barry Bonnell. Rick Kehoe, later a National Hockey League star, played for the team from Windsor, Ontario, and Mack Brown, who coached the University of Texas football team to the 2005 national championship, played for the team from Nashville. Wilson Freight lost both its games in the tournament. Parker was not a member of the Wilson Freight team that won the Connie Mack World Series in 1968.

11 It was a horrible draft for the Pirates. Of the 13 players they selected before Parker, only John Caneira reached the majors, and he played only eight games. And of the 46 players they took after Parker, only 23rd-round pick Ed Ott played in the majors.

12 Charley Feeney, “On Playground or Battlefield, Parker Is BIG.”

13 Roy Blount, “A Loudmouth and His Loud Bat.” The Reds didn’t do any better job drafting than the Pirates did in 1970. Of the 13 players Cincinnati selected before Parker was taken, only Ray Knight, Will McEnaney, and Tom Carroll reached the majors.

14 The Sporting News, June 20, 1970: 6.

15 Charley Feeney, “Danny Juggles Bucs, a Tribute to Parker’s Bat,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1974: 12.

16 His most valuable player award is mentioned in the Pirates 1974 Press-TV-Radio Guide: 34. Parker’s high-school classmate Bill Flowers led the league in runs scored and stolen bases.

17 Bob Hertzel, “Reds Rained Out; Bucs’ Parker Wants to Make It Big Without Tag of ‘Another Clemente,’” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 1974: 38.

18 Hertzel, “From Crosley to the Majors.”

19 Parker didn’t have enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting championship; the official league leader hit .343.

20 Charley Feeney, “Needless Slide May Put Clines on Shelf for ’73,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1973: 28.

21 Details of Parker’s assists can be found at http://prestonjg.wordpress.com/2015/08/08/dave-parkers-remarkable-26-assists-in-1977/.

22 “[Pirates broadcaster] Bob Prince made it famous, but Tony Bartirome gave me the nickname,” Parker said in 2012. http://blackandgoldworld.blogspot.com/2012/07/dave-parker-talks-coaching-hall-of-fame.html. Prince’s Associated Press obituary and his biography included in the SABR BioProject both credit Prince with the nickname.

23 Roy Blount, “A Loudmouth and His Loud Bat.”

24 Ron Cook, “Dave Parker Deserves a Little Respect,” Beaver County (Pennsylvania) Times, April 6, 1980: C-4.

25 Phil Musick, “ ‘I’m Pursuing the Ultimate…,’” Sport, June 1979: 15.

26 Jerry Reuss, Bring In the Right-Hander!: My Twenty-Two Years in the Major Leagues (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

27 Charley Feeney, “Fireworks Start in 9th as Mets Barely Nip Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 1, 1978: 11.

28 Parton Keese, “4-Run Rally in 9th Beats Pirates, 6-5,” New York Times, July 1, 1978.

29 Charley Feeney, “Parker Eyes Quick Return to Buc Lineup,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 3, 1978: 11.

30 Paul Lukas, “Aggh! It’s Dave Parker at the Plate!” http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/page2/story?page=lukas/080724.

31 Charley Feeney, “Parker’s a Bitter Cookie … Not Enough Sugar,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977: 9.

32 Charley Feeney, “Parker-Pirate Contract Duel Leaves Everybody Puzzled,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1978: 44.

33 Jack Lang, “Parker Wins MVP as He Hits – Convincingly,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1978: 59.

34 In a front-page story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on January 27, Charley Feeney wrote that Parker “probably” received “a five-year package worth, including bonuses and fringe benefits, $5 million.” The headline in the New York Times story of January 27 referred to a “$5 million contract,” with Murray Chass calling it “a mammoth deal believed to be worth at least $5 million.” Roy Blount, in his April 1979 Sports Illustrated cover story, wrote that the contract was “worth more than $1 million a year,” and there are many such references after that. Parker even referred to himself as “the first million-dollar player” in a Sport magazine story in June 1979.

35 David L. Snyder, “The Cobra’s Contract: Revisiting Dave Parker’s 1979 Contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates,” Albany (New York) Government Law Review, January 2012, Vol. 5, Issue 1, online at http://albanygovernmentlawreview.org/Articles/Vol05_1/5.1.188-Snyder.pdf. Snyder says the contract called for payments continuing into 2008, even though 222 monthly payments beginning in January 1989 would seem to end in 2007.

36 Jim O’Brien, “The Cobra Strikes Back: ‘I’m the Best Player in Baseball,’” Sport, June 1981: 14.

37 Jim Murray, “Pirates’ Dave Parker Is Earning His Keep and, at $10,000 Per Base Hit, Then Some,” Ottawa (Ontario) Citizen, October 11, 1979: 25.

38 Dan Donovan, “All-Star MVP Parker Guns Down AL, 7-6,” Pittsburgh Press, July 18, 1979: C-10. The throws can be seen at http://youtube.com/watch?v=RkCE6JHUb00.

39 Charley Feeney, “Next Spring Parker ‘Can Talk Baseball,’” The Sporting News, November 24, 1979: 49.

40 Hal McCoy, “Parker: He’s Worth Every Penny to Reds,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1985: 21.

41 Phil Musick, “A Cobra Among the Cuties,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 8, 1980: 13.

42 John Clayton, “Parker Feeling Mighty Low After Assault With Battery,” Pittsburgh Press, July 21, 1980: B-5.

43 Dan Donovan, “Parker Still Shaken, Wants to Be Traded,” Pittsburgh Press, July 22, 1980: C-6.

44 Norm Clarke, “Parker Demands Trade,” Sumter (South Carolina) Daily Item, July 23, 1980: 1B.

45 Charley Feeney, “It’s Open Season on Bucs’ Parker,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1980: 17.

46 Associated Press, “Parker’s Wife Seeks Divorce,” Tuscaloosa (Alabama) News, August 4, 1980: 13. Dave and Stella met in 1973, and her divorce petition claimed they were married by common law in April 1974. “Stella ‘Parker’ Now Tells Her Story of ‘Divorce,’” Jet, September 25, 1980: 46. Parker was listed as married in the Pirates’ 1978 media guide but was shown as single in 1979 and 1980, when apparently the couple lived apart. “She’s an intelligent lady and I had considered marrying her,” Parker said after the divorce filing. “But she became too confining so we had to part.” Norman O. Unger, “Dave Parker Talks About Fears, the Heckling Fans, Lawsuit of ‘Wife’ and Woes of Fame,” Jet, September 18, 1980: 54.

47 Jane Gross, “For Parker, a Season of Insult and Injury,” New York Times, September 14, 1980.

48 Ibid.

49 “Dave Parker Becomes Latest Pirate Casualty,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1981: 30.

50 Charley Feeney, “A Talented Moreno Deserves Applause,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1981: 28.

51 Charley Feeney, “Parker Remains in Pirate Family,” The Sporting News, December 26, 1981: 43.

52 Bill Conlin, “Dawson, Schmidt Hot MVP Rivals,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1981: 25.

53 Charley Feeney, “Moreno to Ask Bucs for Five-Year Pact,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1981: 20.

54 Charley Feeney, “Bucs Get ‘Steal’ in McWilliams,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1982: 26; Charley Feeney, “Parker Has Surgery for Injured Thumb,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 15.

55 Dave Nightingale, “The Resurrection of Dave Parker,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1986: 12.

56 Stan Isle, “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1983: 13.

57 Associated Press, “Formality Rules in Re-entry Draft,” Nevada (Missouri) Daily Mail, November 8, 1983: 8.

58 United Press International, “Dave Parker gets married,” Ottawa (Ontario) Citizen, February 16, 1984: 43.

59 Erik Malinowski, “Swing Away: The Untold Story of the First Home Run Derby,” foxsports.com, July 10, 2014, http://foxsports.com/mlb/story/swing-away-the-untold-story-of-the-first-home-run-derby-071014.

60 Jan Ackerman and Carl Remensky, “Parker: Used Cocaine for 3 Years,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 12, 1985: 1.

61 Michael Goodwin, “Baseball Orders Suspension of 11 Drug Users,” New York Times, March 1, 1986.

62 Greg Hoard, “Pirates Seek to Stop Parker’s Deferred Pay,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 22, 1986: C-1.

63 Ira Berkow, “The Dispute Over Parker’s Contract,” New York Times, April 26, 1986.

64 Associated Press, “Pirates Say They’ve Settled Drug Suit Against Parker,” Los Angeles Times, December 13, 1988.

65 Bob Hertzel, “Pirates, Parker Reach Out-of-Court Settlement,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1989: 52.

66 Kit Stier, “A’s Loss of Parker a Bitter Pill,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1988: 26.

67 David Bush, “Parker Gives A’s Winning Look,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 15, 1989: D1.

68 Ray Ratto, “Parker Signs With Brewers,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 4, 1989: D1.

69 Jon Newberry, “Franchise Businesses Opening Doors of Opportunity,” Cincinnati Business Courier, December 31, 2007. http://bizjournals.com/cincinnati/stories/2007/12/31/story4.html.

70 Elliott Teaford, “Competitive Spirit: Fire Still Burns Inside Bowa, Parker, Who Will Bring That Intensity to the Angels,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1997.

71 Associated Press, “Coach Parker,” Southeast Missourian (Cape Girardeau, Missouri), March 14, 1998: 3B.

72 Joe Starkey, “Ex-Pirates Slugger Parker Is Coping With Parkinson’s,” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, August 5, 2013. http://triblive.com/sports/joestarkey/4480502-74/parker-parkinson-pirates#axzz3w2BUywTW.

73 http://daveparker39foundation.com/foundation.html.

74 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, (New York: Free Press, 2003), 976.

Full Name

David Gene Parker

Born

June 9, 1951 at Grenada, MS (USA)

Died

June 28, 2025 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.