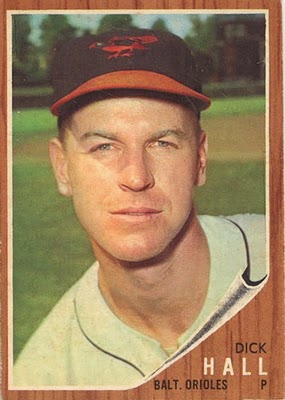

Dick Hall

In June 1970 Ted Williams, then managing the Washington Senators, reminisced for a reporter about the first time Williams had ever seen Dick Hall pitch. Hall, Williams recalled, “was taking his warmup throws, having come in to relieve somebody. I was kneeling in the on-deck circle and I thought to myself, ‘Oh, boy, he’ll be nice to hit.’ But was I wrong! He’s a pinpointer. He’s here and he’s there – never throwing in the same spot twice. You never get a fat pitch to hit.”

In June 1970 Ted Williams, then managing the Washington Senators, reminisced for a reporter about the first time Williams had ever seen Dick Hall pitch. Hall, Williams recalled, “was taking his warmup throws, having come in to relieve somebody. I was kneeling in the on-deck circle and I thought to myself, ‘Oh, boy, he’ll be nice to hit.’ But was I wrong! He’s a pinpointer. He’s here and he’s there – never throwing in the same spot twice. You never get a fat pitch to hit.”

By 1970, Williams had lost none of his appreciation for the tall (6-foot-6½), right-handed reliever. If anything, Williams concluded, “his control is sharper. You can’t wait around for him to walk you. You’d better go up there swinging.”1

Indeed, Williams wouldn’t be the only hitter left with that impression. In his 16 major-league seasons as a pitcher, Richard Wallace Hall displayed remarkable control, and even to the age of 40 proved a durable and effective relief pitcher. He was the consummate control artist, who seemed to get better with age. Asked in retirement to what he attributed his uncanny ability to avoid issuing bases on balls, Hall responded: “Partly it’s concentration; partly I was just born that way; and partly I just played a lot.”2 Whatever the explanation, as former major-league pitcher and longtime Baltimore Orioles announcer Rex Barney wrote, “It looked like anybody in the world could hit him, but he knew where to throw the ball. Location, location.”3 As Barney and countless others for so long admired, Dick Hall threw “nothing but strikes.”4 Over the final seven years of his career, a period that spanned 462 innings, Dick Hall issued a total of only 23 unintentional walks.

Hall didn’t begin his major-league career as a pitcher. At Swarthmore College, a prestigious private university in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, Hall majored in economics (graduating with a bachelor’s degree in January 1953) and minored in history and political science. He also earned 11 athletic letters in five sports. In basketball, Hall was twice named All Conference; in football, he won honorable mention Little All-America after catching 24 passes and scoring nine touchdowns in 1948; and in track, for many years Hall held the school broad jump record, at 23 feet one-half inch. He also scored a goal as a substitute on the soccer team.

Hall’s greatest athletic success, however, was on the baseball diamond. By the time he began his college career, he hadn’t played the game very long. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, on September 27, 1930, Hall lived there only five months before his family relocated for five years to Albany, New York, and then for 10 years to Bergen County, New Jersey. In New Jersey, he attended Tenafly High School for a year and a half, then for the next 2½ years attended Mount Hermon School, in Massachusetts, from which he graduated. Growing up, Hall didn’t play a lot of baseball; “I always played softball as a kid,” he said.5 It wasn’t until he was 16 years old, by which time the family had relocated to the Baltimore area, that Hall began to play baseball. He was a member of a 16-year-old team that won the Cardinal Gibbons championship, and that, he said, “was my first taste of baseball.”6

At Mount Hermon School (now Northfield Mount Hermon school), Hall was a versatile athlete, participating in baseball, football, and basketball. That experience prepared him for athletics at Swarthmore, where he became a baseball star. Pitching and moving to center field when he was not on the mound, in three years Hall batted an impressive .464. Swarthmore played a schedule of only 13 games, Hall later remembered, but in that time he stroked seven home runs. As a pitcher, Hall averaged 15 strikeouts per game and posted an earned-run average of 0.67 in his junior year. He also played summer baseball for two seasons in the Susquehanna League, and semipro ball for East Douglas, Massachusetts, in the Blackstone Valley League.

By Hall’s junior year at Swarthmore, major-league scouts were showing up to watch him play, and all 16 teams expressed interest in signing him. Fifteen of the teams were interested in him as a pitcher, but the Pittsburgh Pirates and their general manager, the legendary Branch Rickey, were interested in Hall as a hitter. In September 1951, after an impressive late-summer tryout before Rickey at Forbes Field, Hall signed for a bonus of $25,000. (There are numerous speculative accounts of the size of Hall’s bonus, ranging from $25,000 to $45,000. In a 1999 interview, however, Hall remembered the amount as $25,000.)

In 1960, when Hall was pitching for the Kansas City Athletics, the scout Jocko Collins recounted how he had scouted Hall at Swarthmore. “I saw him pitch and play the outfield often,” Collins recalled. “The difference is that he has learned how to pitch. … I liked Dick a lot and recommended him highly [to the Phillies]. I liked him as an outfielder. He had size, power, speed, and a big-league arm that was something extra. … He hit the fastball good, but was a little weak on the curve. … His running, throwing, and fielding certainly were good enough for the majors. To be a real good major leaguer he had to improve his hitting. If he had stayed in center, I think he would have done much better.”7 Phillies’ owner Bob Carpenter considered making an offer to Hall but eventually declined because, as he put it, “How can you pay that much for a guy when you don’t even know what position he plays?”8

For three years the Pirates struggled to find a position for Hall. They tried him variously at shortstop, first base, third base, and the outfield, without success. He never developed into a major-league hitter, either, although Pittsburgh made every effort to improve his skills. One day in August 1955, after Hall had switched from hitter to pitcher, he was sitting in the dugout at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium when a reporter asked him what had prompted his change from the batter’s box to the mound. Simple, Hall responded, “I couldn’t hit.”9

Rickey, who loved Hall’s arm and speed, considered the collegian a “can’t-miss” prospect, and thought he’d eventually develop into a fine hitter. Yet after making the team in spring training of 1952, Hall ended that season hitting just .138, with 17 strikeouts in 80 at-bats. Optioned in May to Class B Burlington of the Carolina League, he played 101 games there, mostly at shortstop, and batted .242. In 1953, after starting the season with a handful of games at Burlington, Hall was sent to Waco, Texas, in the Class B Big State League, where he batted .246 and hit six home runs in 95 games. Recalled again to Pittsburgh on September 1, 1952, he appeared in just seven games for the Pirates, this time at second base, and managed just four singles in 24 at-bats, a .167 batting average. Finally, in 1954, Hall spent the entire season with Pittsburgh, yet hit just .239 in 112 games before the Pirates decided he would never be able to hit at the major-league level.

The seeds for the decision to make Hall a pitcher had been planted in Mexico. Beginning in the winter of 1953-54, the Pirates sent Hall south each year to work on his hitting. He played winter ball there for four years and fell in love with the country and its people. “There isn’t enough I can say about Mexico and the people there,” Hall later related. “Playing ball there was pure heaven. Four games a week in a semitropical paradise – how could you beat it?”10

He played in Mazatlan, in the Mexican Pacific Coast League. “We’d play four games every weekend, including Sunday mornings,” he recalled. “That was when you hit the home runs, before the afternoon winds came up.”11 He began the winter of 1953-54 as an outfielder but ended at second base. That winter, in an 80-game season, Hall hit 20 home runs, a league record that was tied by Luke Easter the following winter.

He also found there the love of his life in Mexico. During that first winter he met Maria Elena Nieto; they were married on December 31, 1955, and would ultimately produce three daughters and a son.

“She was queen of the Mazatlan ballclub,” Hall said. “She participated in the opening-day ritual. At the time she didn’t speak English, so it was up to me to speak Spanish. I learned more in Mexico than I did in college.”12 Ultimately, Hall learned to speak the language fluently, and for the rest of his career would always engage his Latin teammates in conversation in their native language. Brooks Robinson, who became one of Hall’s closest friends, related that during the 1970 World Series, when the American players were asked by the Latin press for interviews, “we grabbed Dick Hall to serve as interpreter. He’s married to a beautiful gal from Mexico and speaks Spanish like Juan Valdez.”13

Hall began to pitch in the winter of 1954. At Mazatlan, the team was managed by a man named Memo Garibay, and in a 1970 interview Hall credited Garibay with getting him “interested in pitching.” Hall elaborated: “In the winter of 1954-55 Mr. Rickey sent me down to Mexico … to work on my hitting, and I told Memo I had done some pitching in college and could help out in the pinch. We got in a bind one day and he called me in from center field. I pitched two scoreless innings, I think it was, and ended up winning the game. Memo said, ‘I think your future is on the mound.’ ”14 (In Hall’s last season in the league, he set a league ERA record of 1.20.)

Hall, the Pirates decided, would become a pitcher.

In April 1955, in what was meant to be a developmental period, Hall was optioned to Lincoln, Nebraska, the Pirates’ entry in the Single-A Western League, and was sensational. Playing alternately at both pitcher and left field, in two months Hall won 12 games and led the league in winning percentage (.706) and ERA (2.24); he also led the club with a .302 batting average. So good was he that on July 21 the Pirates recalled Hall and inserted him into their starting rotation.

He made his first start on July 24, and it was quite memorable. Facing the Chicago Cubs at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, Hall struck out 11 in a 12-5 Pirates win. At the time he had no idea that the team record for strikeouts in a game was 12, set by Babe Adams in 1909. “I didn’t know I was anywhere near the record,” Hall later remembered, “until someone told me after the game. I just kept firing away.”15

Not having had much time to develop as a pitcher, Hall’s pitch selection at the time was minimal. “I had only a fastball and control then,” he said, “and all I knew was to throw hard and get the ball over.”16

In time, he expanded his repertoire. When Hall was later playing for the Phillies, in 1967, the press reported that the tall right-hander “knows all the tricks of pitching” and “throws harder than he seems to.” By then he threw three pitches, having added to his “sneaky fastball” both “a good slider and fine change.” Of utmost importance, it was also noted, Hall “can hit a dime with any of his pitches.” Yet he threw with a delivery that was anything but efficient. “The ball comes right out of his shirt,” a sportswriter wrote, “because of the unusual, awkward-looking motion he uses.”17 The delivery made it difficult for hitters to pick up the ball as it left his hand.

Hall admitted that his delivery looked awkward. “The best description I’ve heard of what I look like on the mound,” he said, ”is a drunken giraffe on roller skates.”18 A reporter once described the delivery this way: “He draws his arm back and strides stiff-legged toward the plate, then when his arm is only halfway back, he brings it forward sidearm and delivers not too fast.”19 It might not have been the classic way to pitch, but no one could argue with the results.

By the end of 1955 the Pirates had penciled Hall into their rotation for the following season. Appearing in 15 games in 1955, with 13 starts, he ended with a 6-6 record and a 3.91 ERA. But instead of a continuation of that relatively successful debut, the next several years proved disastrous. During Hall’s first winter pitching in Mexico, Rickey had encouraged him to try to develop a pitch to supplement his fastball. Rickey suggested a knuckleball. Rather than mastering the knuckler, though, Hall injured his arm throwing the pitch.

Over the next two seasons, as Hall battled his injury, he pitched just 72 innings and compiled an 0-7 record. He was on the disabled list once in each season, and was unable to recover his effectiveness. Finally, Pirates manager Bobby Bragan, who admittedly “wasn’t a Dick Hall man from the start,”20 had seen enough, and on June 17, 1957, Hall was assigned outright to Columbus. There he pitched 91 innings in 14 games and finished with a record of 4-7.

Hall didn’t pitch at all in 1958. Two noteworthy things happened that year, though. First, he was transferred to the Pirates’ Salt Lake City affiliate. During spring training with Salt Lake City, Hall developed hepatitis and spent the entire season on the voluntarily retired list. Out of action for the year, Hall conscientiously prepared himself for a post-baseball career by studying accounting at the University of Utah’s Graduate School of Business. It was a move that served him well once his baseball career was finished.

As it turned out, his career was just getting started. By 1959 Hall’s arm was finally healthy and he celebrated with a wonderful season. That year, pitching in Salt Lake City, Hall led the Pacific Coast League in wins (18), percentage (.783), ERA (1.87), and shutouts (6) and was named the PCL’s Most Valuable Player. Interviewed years later, Hall remembered that he won $55 that season, too. Larry Shepard was the Salt Lake City manager. At the beginning of the season, Hall said, Shepard told the mound staff, “If you pitch an entire game, win, and walk no one, I’ll give you $5.”21 The result was Hall’s $55 windfall.

With confidence in the right-hander seemingly renewed, the Pirates recalled Hall in September 1959; he pitched in two games, made one start, didn’t earn a decision, and walked only one in 8 2/3 innings. But that marked the end of his Pirates career. On December 9, Hall was traded, along with infielder Ken Hamlin and a player to be named later (eventually catcher Hank Foiles), to the Kansas City Athletics, for catcher Hal Smith.

The trade was “a real shock,” Hall recalled. “I’d been in the Pittsburgh organization eight years, when all of a sudden I got traded.” Moreover, “I couldn’t name a single player on the Kansas City team.”22 His feelings weren’t assuaged any when the Pirates went on to win the World Series in 1960, while the Athletics finished last in the American League.

Yet Hall was renewed in Kansas City. Used as a starter throughout the year (28 starts of his 29 games), he finished the season 8-13 with an ERA of 4.05. Impressively, too, he walked just 38 batters in 182? innings. Then he was traded again. On April 13, 1961, Kansas City sent the 30-year-old Hall and outfielder Dick Williams to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher Jerry Walker and outfielder Chuck Essegian. This time, Hall recalled, “I was fine” with the trade.23 And over the next six years he developed into a vital component of the Orioles’ pitching staff, first as a starter and eventually as a reliever as his “elbow again gave me trouble.”24

By the mid-1960s Hall had become one of the premier relievers in the game, largely by virtue of his hard work. Indeed, noted the press, “No player is more attentive to training and mechanics than the scholarly Swarthmore grad.”25 Coach Jim Frey commented: “Turkey is one of the best-conditioned players I’ve ever seen.”26 The rewards for Hall’s hard work were impressive ERAs (3.09, 2.28, 2.98, 1.85, and 3.07 from 1961 through ’65) and a paucity of walks.

Although he developed a reputation as an intellectual (“a brilliant guy,” was how Rex Barney described him27).Hall’s approach to pitching was rather simple. With his unique delivery (“A lot of people say, oh, you were a side-arm pitcher, but I really threw ‘short-arm,’” he remembered28), Hall threw a rising fastball, and “I’d just throw on the outside corner, trying to get them to hit it to center field.”29 As a result, batters “couldn’t hit down the line,” and “when I was throwing good, I’d throw a lot of pop-ups and fly balls.”30

In 1963 he won five games and saved 12, but his most impressive stretch occurred between July 24 and August 17, during which Hall retired 28 men in order. “That was my first perfect game,” Hall said. “I never had one before and this one took 25 days.”31

During those years, Hall also gained renown as a Yankee killer. In 1963 and ’64, over a span of 12 relief appearances against New York, he pitched 22 innings, allowed only two runs, and posted a 4-1 record, with four saves. “I know he’s been good against us for a couple years,” said manager Yogi Berra at the time, “but I don’t know why. The ball sure looks good to hit, but we don’t hit it.”32 On June 24, 1964 in Baltimore, in the top of the eighth inning, Bobby Richardson and Mickey Mantle singled with no outs, and Hall promptly retired the next three hitters on three pitches.

Between 1961 and 1966, Hall’s record with the Orioles was 44-27 (.620), with 48 saves. In 599? innings, he allowed 496 hits and walked only 100, 29 intentionally. By 1966, though, Hall’s ERA had soared to 3.95; midway through the season he developed tendinitis near his right elbow, and the pain limited his work. He didn’t pitch at all in the Orioles’ World Series win that year over the Dodgers, and he wasn’t surprised when Orioles’ General Manager Harry Dalton called him at 1 o’clock on the morning of December 16 to tell Hall he’d been traded to the Phillies for a player to be named later. “Looking at it objectively,” Hall told the Philadelphia press, “it wasn’t much of a shock.”33

In 1967 Hall was outstanding for the Phillies, posting a 2.20 ERA with eight saves in 86 innings. On June 15, he made his first start in four years, replacing an ailing Jim Bunning and recording a surprising 4-1 complete-game victory over the Pirates at Connie Mack Stadium. However, the following year he again developed a sore elbow, pitched just 46 innings, posted an ERA of 4.89, and on October 29 was given his unconditional release. When no team came calling, Hall once again contacted Harry Dalton, who, as Hall remembered, invited the veteran to “come down to spring training; we’ll give you a shot.”34

With the soreness in his elbow gone after a winter’s rest, Hall pitched 11 scoreless innings in spring training and made the 1969 Orioles. “The way he has looked, Hall could pick up the phone right now and get five jobs,” commented manager Earl Weaver as spring training ended.35 During the regular season, pitching 65? innings, Hall won five games, saved six, and posted a 1.92 earned-run average. Moreover, in the entire season he issued just three unintentional walks.

The 39-year-old finally made a postseason appearance. On October 4, 1969, at Memorial Stadium, in the first American League Championship Series game ever played, Hall was the winning pitcher in a 4-3 Orioles victory over the Minnesota Twins. It was his only ALCS appearance that year. In the Orioles’ World Series loss to the Mets, in Game Four, at Shea Stadium, Hall was charged with the loss.

Three weeks later, Hall took an important test. For eight straight winters he had worked at the accounting firm of Main, Lafrentz; during his illness in 1958, he had also studied accounting. He knew what he would do with the rest of his life, so after the World Series he sat for the CPA exam. Several months later he was notified that he had passed, recording a score that tied him for second in the state of Maryland among several hundred who took the three-day test.

Despite being the oldest active player in the American League in 1970 (he turned 40 on September 27), Hall threw 61? innings and finished 10-5 with an ERA of 3.08 and three saves. He issued just six walks, only four of them unintentionally. In Game One of the 1970 ALCS, again versus Minnesota, Hall was the winner, allowing only one runner in 4 2/3 innings. And in Game Two of the 1970 World Series, in Cincinnati, Hall entered the game in the bottom of the seventh inning with runners on first and second and two outs, and over the final 2? innings retired Tony Perez, Johnny Bench, Lee May, Hal McRae, Tommy Helms, and pinch-hitters Bernie Carbo and Jimmy Stewart to save the Orioles 6-5 victory.

After that appearance, the Reds offered their opinions of the 40-year old veteran’s offerings:

“His pitches don’t seem to be moving, but I guess it’s deceiving. He keeps getting people out,” said Tommy Helms.36

Tony Perez lamented, “He’s got that funny motion. He throws a change-up or a palm ball. I don’t know what it is. Oh, that pitch he gave to me was a good one to hit.”37

And Johnny Bench told reporters, “I tried to go right on him, then I changed my swing and I got all screwed up.”38

During the game, Bench had hollered at Hall from the dugout, “How can you be out there with that garbage?” and Hall had just grinned.39

“Even though I wasn’t throwing too well,” Hall said, “the Reds weren’t hitting the ball squarely.”40

In 1971 Hall was the oldest player in the American League (41), and pitched his final season. In 27 games, he threw only 43? innings, won six games and saved one, but finished with an ERA of 4.98. On October 11, in Game Two of the World Series against the Pirates at Memorial Stadium, he earned a save for Jim Palmer in what turned out to be Hall’s final major-league appearance. It was only fitting that it should be against the Pirates, the team for which it had all begun.

“I guess one of the things I like about baseball,” Hall said in 1970, “is that, unlike football, force isn’t necessary. The pitch comes in one direction, you hit in another, and you run in still another. You might call it a cat-and-mouse game, this battle between the pitcher and hitter. I enjoy it. I like the competitive approach. Yes, I really enjoy the challenges in baseball. And if I can get paid for it, why not?”41

As of 2009 Hall had been married 53 years, and had four children and nine grandchildren. He began working as an accountant during his career, and did it full-time until 2001 and part-time for several years after. He suffered a stroke in 2001, from which he mostly recovered. He told the Baltimore Sun in 2009, “I’ve had one knee replaced and my (right) shoulder is shot – I can’t throw a ball 50 feet. But I can walk and play golf, and that’s good enough.”42 Living in the greater Baltimore area, he played golf twice a week with former Orioles Billy Hunter and Ron Hansen.

For the better part of 19 professional seasons, Dick Hall got paid to throw his sneaky fastball over the outside edge of the plate. And for the better part of 19 years, it’s safe to say that Dick Hall provided a pretty good return on that investment.

Notes

1 Ed Rumill, “The pitching machine: Hall has ‘built-in file on every hitter,’” Christian Science Monitor, June 25, 1970.

2 Dick Hall, interview, SABR Oral History database, conducted November 22, 1999. (Part 1 can be heard here, Part 2 here.)

3 Rex Barney with Norman L. Macht, “Rex Barney’s Orioles Memories, 1969-1994” (Woodbury, Connecticut: Goodwood Press, 1994), 137.

4 Barney and Macht, “Rex Barney’s Orioles Memories,” 212.

5 Hall, interview.

6 Hall, interview.

7 Unidentifed clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

8 Ray Kelly, “Swarthmore’s Dick Hall is Finally ‘Put in His Place’; Pitching Well for Bucs,” Philadelphia Sunday Bulletin, August 14, 1955.

9 Kelly, “Swarthmore’s Dick Hall.”

10 Unidentifed clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

11 Unidentifed clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

12 Unidentifed clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

13 Brooks Robinson with Fred Bauer, Putting It All Together (Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1971), 58.

14 Phil Jackman, “Hall Credits Ex-Manager,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1970.

15 “Comeback Kid,” unidentified clipping in HOF file, July 25, 1955.

16 Unidentified clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, June 16, 1967.

17 Unidentified clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, July 1, 1967.

18 “Cincinnati Joins Mexico in Hall’s Legend,” Newsday, October 12, 1970.

19 “Cincinnati Joins Mexico.”

20 Unidentified clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, July 17, 1967.

21 Hall, interview.

22 Hall, interview.

23 Hall, interview.

24 Hall, interview.

25 Unidentified clipping in Dick Hall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, July 10, 1965.

26 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Hall Stands Tall; Orioles Go Two Up,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1970.

27 Barney and Macht, “Rex Barney’s Orioles Memories.”

28 Hall, interview.

29 Hall, interview.

30 Hall, interview.

31 Doug Brown, “’Perfect Game’ by Reliever Hall; Retired 28 in Row over 25 Days,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963, 10.

32 Doug Brown, “Hitters Flunk in Facing Scholar Hall: Oriole Bull-Pen Ace Looks Awkward, Has Jerky Style,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1964.

33 Doug Brown, “Hall Newest Victim Of Player Rep Jinx,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1966, 28.

34 Hall, interview.

35 Doug Brown, “Dick Hall Tireless and Oriole Retread,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1969, 4.

36 Baltimore Sun, October 12, 1970.

37 Baltimore Sun, October 12, 1970.

38 Baltimore Sun, October 12, 1970.

39 “Cincinnati Joins Mexico in Hall’s Legend.”

40 “Cincinnati Joins Mexico in Hall’s Legend.”

41 Ed Rumill, “The pitching machine.”

42 Mike Klingaman, “Catching up with ex-Oriole Dick Hall,” Baltimore Sun, May 26, 2009.

Full Name

Richard Wallace Hall

Born

September 27, 1930 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.