Don Schwall

In his book The Boys of Summer, author Roger Kahn relates how even after leaving daily 1950s baseball coverage to write for magazines, his “journalistic identity, such as it was, lived with my [New York Herald] Tribune stories” on the then-Brooklyn Dodgers. Robert Frost consoled him, telling Kahn that “nearly everyone has to lead two lives at the very least.”1

In his book The Boys of Summer, author Roger Kahn relates how even after leaving daily 1950s baseball coverage to write for magazines, his “journalistic identity, such as it was, lived with my [New York Herald] Tribune stories” on the then-Brooklyn Dodgers. Robert Frost consoled him, telling Kahn that “nearly everyone has to lead two lives at the very least.”1

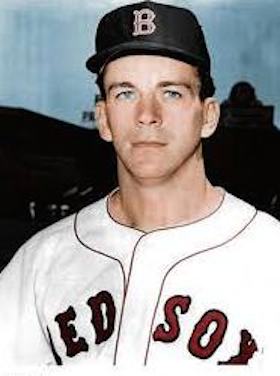

To America’s baseball public, Don Schwall is remembered as the 1961 American League Rookie of the Year, a 6-foot-6 inch, 200-pound Boston Red Sox right-hander who brought rare pitching skill to the age’s Olde Towne Team. The former University of Oklahoma basketball center, who once outscored Wilt Chamberlain, lived a Zelig-like second life as well, witnessing some of baseball’s greatest 1960s stars, trends, and sites.

Schwall became a fine starter-turned-reliever, pitching in perhaps baseball’s most beautiful parks – Fenway Park and Forbes Field. At Boston, he saw Ted Williams retire, and Carl Yastrzemski break in. At Pittsburgh, he pitched with Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, and Bill Mazeroski behind him. He then joined the Atlanta Braves, gaping at Henry Aaron. For a time Schwall must have thought there were no titans that he missed.

Let us relive Schwall’s two identities – his 1961 Rookie of the Year season, and his 1961-67 career that began in the Fens and ended in Atlanta. Symmetrically, he was born in and ultimately returned to Pennsylvania: birth March 2, 1936, in Wilkes-Barre, a coal-mining area 112 miles north of Philadelphia and 128 miles west of New York City. “Lots of Phillies and Yankees fans,” Don laughed, not as many following his former Sox, Bucs, and Braves 2 He now lives in Gibsonia, eight miles from Pittsburgh.

Schwall’s father, Herman, a coal miner, was one of ten brothers. In World War II, almost all of his family moved to Michigan to build B-24 bombers. Don played baseball, basketball, and football at Ypsilanti High School. His hoops earned a University of Oklahoma scholarship, where the All-Big Eight 1956-57 star led the Sooners over Chamberlain’s Kansas Jayhawks, thrice outscoring and outrebounding the Stilt – “in one game I had 30 points and Wilt 11” — and averaging 15.1 points a game. Still, Don loved baseball, at age 10 seeing his first game at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium. “It was against Boston, and Ted Williams became my idol.” As a Sooner varsity pitcher Schwall threw little, but quickly when he did.

Baseball’s major-league draft began in 1965. Before then, money could dictate with which club a prospect signed. One day in 1955 the freshman Schwall left basketball practice for the Oklahoma baseball field. In the stands sat Red Sox scout Wog Rice. Picking up a baseball, Don threw strike after strike. “I was amazed when he started firing,” said Rice, who later introduced himself. “In ten minutes I knew I had a red-hot prospect if I could only sign him.”3 In summer 1957, Schwall pitched in the Basin League, an amateur league in South Dakota, with future big leaguers like Jim O’Toole and Eddie Fisher. Mentally, Don was retrieving the pastime of his childhood.

Pining to keep him, Sooner basketball coach Doyle Parrack tried, among other things, to hide Schwall from baseball scouts on a late 1957 basketball trip out West. “Usually, we’d fly home next day after a night game,” said Don. “Coach had us leave right after the game so that no scouts could contact me.” It didn’t work. Rice signed Schwall for a $65,000 bonus which included his first five years of minor-league salary. “I hate to see him go,” said Parrack, “but for that money, nobody can blame him.”4 Schwall left Oklahoma several credit hours short of getting a B.A. in Business Administration. At 22, the young man in a hurry joined the Red Sox system in 1958.

That year the rookie went 7-5 for Class D Midwest League Waterloo, Iowa. In 1959, promoted to the Class D Sophomore League club in Alpine, Texas, Schwall finished 23-6, with 199 strikeouts. Joining the 1960 American Association Triple-A Minneapolis Millers, Don was 16-9 with a 3.59 earned run average. Teammate Carl Yastrzemski hit .339 to win the batting title. Sports Illustrated [S.I.] wrote: “Boston fans may find [Yaz’s] name hard to pronounce, but they will not find him hard to take.” 5 Yaz signed for a $100,000 bonus. In 1960, Boston played an exhibition against Minneapolis. “We were all curious,” said Sox voice Curt Gowdy, “so I ask a guy, ‘Which one’s Yastrzemski?’ He pointed to a figure swinging a couple of bats, and I said, ‘That little guy?’ Not really, but I expected a giant after seeing Williams.”6

To Schwall, Williams was “the best hitter I ever saw. If he hadn’t spent five years in the service” – 1943-45 during World War II and 1952-53 in Korea – “his numbers would have been even better.” Elegant as a stallion, long-limbed as a pelican, and high-strung as a colt, the 6-foot-4 inch Kid literally stopped batting practice. From 1939-42 and 1946-60, he hit .344, had a franchise-high 521 home runs, led the A.L. six times in batting, four times in homers and RBIs, and twice won the Most Valuable Player award and Triple Crown. In 1960, The Kid hit his 500th home run, batted .316, and helped the Sox draw 1.1 million, the last time they passed 1 million until 1967. Most came to bid him an affectionate farewell.

On September 28, 1960, Boston hosted Baltimore. Like a deity, Williams homered in his final big-league at-bat. Calling it, Gowdy remembered being “choked up. My heart was pounding – unbelievably emotional.”7 With Ted’s retirement official, New England was about to learn, wrote Ed Linn, “how England felt when it lost India.”8 Schwall met Williams next year at spring training in Arizona. “I’m in the clubhouse, and feel this tap on my shoulder,” said Don. “I turn around, and there’s my hero saying, ‘Don Schwall, Minneapolis, 16 and 9, 3.59 ERA.’ Ted [a Sox special instructor] knew my ’60 stats, then started ragging me.” He then invited Don to dinner at a restaurant on a mountain overlooking Scottsdale. “For some reason he took a liking to me. We talked hitting and pitching. Mostly I listened, trying to learn.”

For Carl Yastrzemski, learning officially began April 11, 1961 with his first of 3,419 hits. By June, he averaged .213, then straightened up, tried to pull, and rose to .266. “My rookie year was very difficult,” Yaz said. “We had a lousy team.” (The ’61 team placed sixth.) “Above all, I was playing left field, where Williams played, and there was that pressure.”9 In 1961, Schwall felt pressure, too, promoted on May 16 from Seattle of the Pacific Coast League, Boston’s other Triple-A affiliate. Former Sox All-Star Johnny Pesky was the Rainiers manager. As Schwall recollected, “He called me in and said, ‘[Boston’s] Tom Brewer’s hurt his shoulder, and I recommended you to go up.” Schwall was then 3-1 in the PCL. “That meant nothing in the majors,” Don said. What meant something was his electric start with Boston.

Schwall debuted May 21, winning the second game of a doubleheader against the White Sox. He next beat Baltimore twice, including a shutout, then Kansas City and Minnesota in June. He relaxed before a game by playing five-handed poker – alone. “I’ve been doing this a long time. And as long as it works, I’ll keep on doing it.”10 On July 13, Schwall’s record was 8-2. Said manager Mike (Pinky) Higgins: “He’s got ice-water in his veins.” Fifteen days later he was 11-2, at which point the drop-dead righty — tall, dark, with a mass of brown curly hair – suffered a lingering kidney infection. Don’s rookie season ended on an historic, if not pleasant, note: On September 23, 1961, in his first at-bat of the day against Schwall, Mickey Mantle hit his 54th and final home run of the year.

“We were on the downside,” announcer Ned Martin said. Jackie Jensen had returned after retiring a year earlier because he hated flying. In 1961, he jumped the club and went home for good. Center fielder Gary Geiger’s 18 homers paced a punchless team. Shortstop Don Buddin would snare the ball in the hole and then throw it a time zone above the first baseman’s glove. By contrast, Bill Monbouquette struck out a then-Sox record 17 batters in a game. Rookie second baseman Chuck Schilling fielded like future Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr. Pete Pete Runnels hit .317 in 1961, bookended by his 1960 and 1962 batting titles. At third base, Frank Malzone “can hit, he can field, and he’s the best in the league at his position,” said S.I. “Boston just wishes he were triplets.”11

None of the above matched Boston’s 1961 high meridian – the second All-Star Game. From 1959-62, baseball played two All-Star Games each season to benefit the players’ pension program. In mid-May 1961, Schwall hadn’t even thrown a pitch in the major leagues. Incredibly, on July 31 he threw the maximum three innings allowed in a Mid-Summer Classic, before 31,851 at Fenway – one of the few players to start a season in the minors and, that same year, make a big-league All-Star team. Jim Bunning and closer Camilo Pascual pitched innings one-three and seven-nine, respectively, holding the N.L. hitless. Schwall yielded five hits and the only run in the middle three, at the time calling his strikeout of Stan Musial “my biggest thrill in baseball so far.”

Rocky Colavito’s first-inning homer was the American League’s sole run. The game was postponed by rain at the end of the ninth inning – until 2002’s 7-7 fiasco at Milwaukee, the All-Star Game’s only tie. A.L. manager Ralph Houk chose Sox skipper Higgins, reliever Mike Fornieles, and Schwall, who seemed dwarfed by that year’s M&M boys, teaming for 115 homers. “I’ve got a picture hanging in my office of Mantle and Roger Maris with me at the All-Star Game,” Don said. “I don’t think there is any question that playing when I did was one of the great eras of baseball. Just look at all of the Hall of Fame guys I played with…. How about the N.L. outfield? Clemente, Aaron, Willie Mays.”

Schwall, only 25, made the Topps All-Star Rookie Team, took the United Press International A.L. Rookie of the Year Award, and won the Baseball Writers Association A.L. Rookie of the Year Award, getting seven of the latter’s 20 votes to Kansas City shortstop Dick Howser’s six. Schwall finished 15-7, completed 10 of 25 starts, had two shutouts, yielded 167 hits in 178 2/3 innings, walked 110, fanned just 91, and had a 3.22 earned run average. He allowed only eight home runs, including five at Fenway, where his ERA was 2.72. Even so, statistician Bill James called Don’s award unusual, noting that Howser batted .280 in 158 games, had 171 hits, 29 doubles, 92 walks, only 38 strikeouts, and 37 steals. “Everyone has a choice,” shrugged Schwall. “That my teammates were glad I won was all that mattered.” Teammate Chuck Schilling got several votes as well.

Another Sox mate batted .296 in 1962, only later becoming a power hitter, ranking in the top eight all-time in total bases (5,539), games (3,308), at-bats (11,988), and walks (1,845). “When Yaz came up, he’d changed since Minneapolis, trying to hit everything to left field,” said Schwall. “That September [1961] he hit a drive 420 feet at Yankee Stadium to right-center. I told him, ‘That’s the way you hit.’” On October 2, 1983, Yastrzemski, by then a first baseman, played left field for the first time since cracking his ribs in 1980. His Hall of Fame plaque reads: “YAZ. Boston, AL 1961-83. Succeeded Ted Williams in Fenway’s left field in 1961 and retired … as all-time Red Sox leader in 8 categories … Only AL player with 3,000 hits and 400 homers. Three-time batting champion, won MVP and Triple Crown in 1967 as he led Red Sox to ‘Impossible Dream’ pennant.”

In 1962, Yaz hit fourth as Schwall lost on Opening Day, 4-0, to Cleveland in the Fens. Don looked ahead to a long run in New England’s cathedral of the outdoors. Like most classic parks, Fenway abutted streets – here, Lansdowne and then-Jersey – forging asymmetry. Center field was 389 feet from the plate, right-center 383, center field’s deepest point – a.k.a. the Triangle – 420. Right and left field – then, 302 and 315 feet, respectively — helped a hitter. Left field’s 37 foot-2 inch-high wall – the Green Monster – drove fielders loco. Right-handers tried to pull Schwall. Left-handers hoped to double off The Wall. “The great Sox hitters have been mostly lefties: Williams, Pesky, Runnels, Yaz, Fred Lynn, Wade Boggs, David Ortiz,” Don said. “I loved pitching there, since I’d pitched lefties inside.” Capacity was only 33,357. Each seat had a good view – if you weren’t behind a post.

An ancient maxim, the sophomore slump, seemed to affect the lanky righty. “Control was my problem,” Schwall said. “Once I mastered it, it was fine.” An Arizona Instructional League report said, “He had developed the bad habit of throwing the ball before his left foot hit the ground and thus wasn’t following through as he normally should.”12 The Sox fell to eighth, attendance to 733,080, and Schwall to 9-15. He had more walks (121) than strikeouts (89), completed only five of 32 starts, and his 4.94 ERA was almost two runs higher than 1961’s. On one hand, he pitched better after the All-Star break, reliever Fornieles calling him “our best pitcher in the second half.” On the other, the Sox seemed to resemble auto racing – going around in circles – and had not shown they grasped how Schwall’s youth and potential made his trade value high.

Then, on November 20, 1962, Schwall and catcher Jim Pagliaroni were dealt to Pittsburgh, whose scout, Howie Haak, had offered Don $30,000 in 1957 only to be outbid by Boston. In return, the Sox got pitcher Jack Lamabe and slugging first baseman Dick Stuart, who treated fielding, to quote Ring Lardner, like a side dish he declined to order. “I learned about it in winter ball,” Don said. “Our manager said, ‘You don’t have to come to practice tomorrow.’ That was my hint.’” The 1963 Pirates were 74-88. Schwall went 6-12, with a 3.33 ERA, three complete games in 24 starts, and 158 hits in 167 2/3 innings. For the first time, strikeouts outnumbered walks, 86 to 74, auguring a future in the bullpen. “I had better control,” he said, “and I knew more about pitching.” A year later, starting and relieving, Schwall was briefly demoted to Pittsburgh’s Triple-A Columbus affiliate, where he was 2-6. Nothing could dim how he had come to love southwestern Pennsylvania.

“Pittsburgh’s informal, easy to grow attached to,” Schwall said of a region settled by Slavs, Poles, Italians, and Germans who stayed en route to the Midwest. On February 2, 1963, he married Patricia Plate, of Burgettstown, Pennsylvania, whom he met at Fenway. “One day I asked Pinky, ‘Can I go and sit in the bullpen? I want to see what they do.’” What relievers did was flirt with bleacherites. Don met Patty, later asked for her phone number, “and the rest is history.” They bought a home in Pittsburgh. Schwall liked another home: Forbes Field, born 1909, the archetypical pitchers park. Right field abutted Schenley Park. Two pavilion decks cut the distance to 300 feet, but a 14 1/2-foot screen topped a 9 1/2-foot concrete wall. Left, center, and right-center field required a 365, 435, and 457-foot poke, respectively. The outfield batting cage, light tower cages, and flagpole bottom were in play. Forbes’ object d’art was an ivied brick wall from right-center field to the left-field line. In left stood a 27-foot high scoreboard. Beyond third base lay bleachers down the line. “A gorgeous park,” said Schwall, who hoped to stick around to enjoy it.

In 1960, western Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, and West Virginia celebrated “Beat ‘Em Bucs,” a record attendance of 1,705,828 at Forbes, and a surreal World Series won by Bill Mazeroski’s ninth-inning Game Seven homer. The rest of the decade Pittsburghers cheered a lineup that today is partly ensconced at Cooperstown. From 1956-72, Mazeroski buoyed 2,163 games, had 2,016 hits, and on the double play treated the baseball as if it were radioactive to his glove – to Schwall, “a genius.” At first base or left field, 1962-82’s Wilver Dornel (Willie) Stargell played in 2,360 games, batted .282, hit a franchise-high 475 homers, and was the Captain in every way. Said Don: “Each year he grew as a person and as a player.”

Above all, The Wonder that was Clemente etched the Pirates then, and now. He had 3,000 hits, led outfielders in assists five times, and won a dozen Gold Gloves and four batting titles. His MVP pinnacle was 1966’s .317 average, 29 homers, and 119 runs batted in. A year later he batted .357. Clemente ran like Secretariat, hit like Ali, and “would shock you in different ways,” said Don. “He made plays with his back to the infield. First baseman Donn Clendenon said relay throws made your hand sting. With one foot in the air Roberto hit a ball four hundred feet.” On New Year’s Eve 1972 he died trying to help earthquake victims in Nicaragua. Today the Roberto Clemente Bridge in Pittsburgh is closed each game day so that pedestrians can cross the Allegheny River, pass the Clemente statue outside PNC Park and, upon entering, see the 21-foot-high right-field wall, its height a tribute to Roberto’s uniform number. “His memory,” Don said, “is everywhere.”

Steve Blass was a star pitcher for the Pirates in the late 1960s and early 1970s. “I’d look around and see Stargell at first, Maz at second, and Roberto in right: three Hall of Famers,” he said. “My attitude was: ‘Hit the ball in their direction, and I’m going for a sandwich. When I come back, you’ll be out.’” In 1965, Schwall relied on them in a new role: relief pitcher. In 1959, Elroy Face finished 18-1. Six years later, hurt, he graced only 16 games. New skipper Harry Walker tapped Schwall to succeed him, using “my sinking fastball, which was pretty good,” said Don. “Eventually, I found that relief was easier. If you started, you were expected then to throw all nine innings. Relieving, you just threw strikes. My only worry was how my arm would hold up pitching each day. You need a different mind-set as a reliever.”

Neither Schwall nor the Bucs minded much about 1965. In 43 games, the ex-starter relieved 42 times, finished 19 games, saved four, and had a 9-6 record and then-career lowest 2.92 ERA. “The big, handsome right-hander,” wrote Les Biederman, pitched in as many innings as hits allowed (77), fanned almost twice as many as he walked (55 and 30, respectively), and “is the Roy Face of 1965.”13 In one 18-inning stretch, Schwall allowed one earned run on a fluke 70-foot single. In a game against the Mets, he inherited a two-on, no-out, ninth-inning 3-0 lead, saving the game on three pitches. The Bucs finished the season in third place (90-72), forged the league’s second-best ERA (3.01), and yielded baseball’s fewest homers (89).

On April 12, 1966, the Pirates opened their season in the South, The Braves had planned to move to Atlanta in 1965 but had to stay another year in Milwaukee due to legal fiat. Freed to move, they debuted against the Bucs at 51,000-seat capacity Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Tony Cloninger pitched a 13-inning complete game for Atlanta. Pittsburgh, however, won, Schwall getting the 3-2 victory. Despite leading the National League in May, the Pirates weakness, General Manager Joe L. Brown felt, was left-handed starting pitching. On June 15, Schwall went to a team as transient as the Bucs were stable — the Atlanta Braves. In return, Pittsburgh got starter Billy O’Dell, who a year earlier went 10-6 for Milwaukee but whose career, like Schwall’s, had begun to ebb.

The 1966 Braves attracted 1,539,801 spectators, though some wondered how well many knew the sport. “One day there were about forty-five thousand people in the stands. You could hear a pin drop,” said catcher Joe Torre. “Fans just didn’t know what to do at a game – such a contrast to Milwaukee.”14 After the trade, Schwall was used sparingly by the Braves: 11 games, including eight starts, two games finished, 3-3 record, 4.37 ERA, and 44 hits in 45 1/3 innings. The work was typical of his career: 172 games, including 103 starts, 34 games finished, 18 complete games, 49-48 record, 3.72 ERA, five shutouts, four saves, almost as many walks (391) as strikeouts (408), and almost as many hits (710) as innings (743). “Looking back I think I decreased my leverage by mixing my status as a starter and reliever,” Don said.

In 1969, the league split into two divisions. Atlanta won the West, luring 1,458,320 patrons but losing the first League Championship Series to New York. Schwall watched as a spectator, having made one appearance for Atlanta in 1967 before being optioned to Triple-A Richmond, then getting his unconditional release on June 20. Like the rest of America, he was left to marvel at No. 44. “Aaron was one of the greatest players of our time,” Schwall laughed, “but couldn’t hit me. He said, ‘I didn’t like your delivery, couldn’t pick up the ball.’ I’d tell him, ‘I wish more hitters had your problem.’” Aaron, Don said, had “enormously strong wrists. In batting practice he’d put on a show — not balls hit 420 feet, but 370, drive after drive. He could have hit .350 each year, but as he’d tell me, ‘The home runs, that’s where the money is.’”

After baseball, Schwall began his investment career as a stockbroker with Francis DuPont Co. He then joined Moore, Leonard, and Lynch in Pittsburgh before moving to E.F. Hutton in the Steel City. Next, Schwall spent ten years with Paine Webber and, finally, ten years for the firm Ferriss, Baker Watts in Washington, D.C. Retiring in 2008, he started a company, Completion Capital Partners, with son Don Jr. His daughter, Damina MacDougald, completes Don and Patty’s clan.

Schwall enjoyed the Braves dynasty that began in the early ’90s: “No one will match its consistency,” he said. Don felt special kinship with the 2004, 2007, and 2013 world champion Red Sox – “It’s great because it seemed so impossible for so long and the Red Sox mean so much to so many.” The Pirates 2013 revival, making the postseason after more than two decades of losing, also moved him and his region deeply. Above all, Don Schwall just loved ball.

Asked if people still recognize him, he said, “Some of them, but you know how that goes.

Older folks may still remember, but not many who are younger.” We recall Schwall’s magical 1961 that came out of nowhere – and his wondrous baseball alchemy of look, sound, and feel. There are far worse identities to have.

Last revised: July 14, 2015

Sources

Books

Smith, Curt. The vast majority of this biography’s material, including quotes, is derived from the books Voices of The Game: The Acclaimed Chronicle of Baseball Radio & Television Broadcasting – from 1921 to the Present (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992); Storied Stadiums: Baseball’s History Through Its Ballparks (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001); Voices of Summer (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005); The Voice: Mel Allen’s Untold Story (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2007); Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2009); A Talk in the Park: Nine Tales of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2010); and Mercy! A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2012).

Articles

Biederman, Les. “Close Outfield Wall Often Ruins Batter’s Timing – Schwall,” Pittsburgh Press, November 24, 1962.

_____. “The Pirates Get Don Schwall Five Years After First Try For Him,” Pittsburgh Press, February 24, 1963.

_____. “Schwall Made Roundabout Trip,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1963.

_____. “Back Ailment Cured – Now Schwall Faces Bright Bucco Future,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1964.

_____. “Don Schwall Hopes His Low-ball Pitching Gets Some Results,” Pittsburgh Press, March 22, 1964.

_____. “Handsome Schwall Expecting Better Deal From Lady Luck,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1964.

_____. “Schwall Pumps New Blood as Pirate Fireman,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1965.

Claflin, Larry. “Slab Ace Schwall Chucked a Cage Career,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1962.

Daniel, Dan. “AL Rookie of Year A Schwall Guy,” New York World-Telegram, December 1, 1961.

Hurwitz, Hy. “Red Sox Give Stallard Shot as Hill Starter,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1961.

_____. “Hub Fans Hailing Frost Hill Dazzler Schwall,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1961.

_____. “Schwall, Bosox Rookie Flash, Sidelined by Kidney Infection,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1961.

McCollister, Tom. “Schwall Ducked Wrong Way,” Atlanta Journal, June 15, 1966.

New York Times, December 10, 1957.

New York World-Telegram, November 21, 1962.

The Sporting News, April 14, 1969.

Online

Baseball-Reference.Com. “Don Schwall – BR Bullpen.”

Emert, Rich. “Where are they now: Don Schwall,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 5, 2002.

Sports Authority. “Don Schwall Baseball Stats, facts, biography, images and video. The Baseball Page.”

Wikipedia. “Don Schwall.”

Personal Correspondence.

Don Schwall. Phone interview on Friday, November 2, 2013. Mr. Schwall and the author spoke for an hour and a half.

Notes

1 Roger Kahn. The Boys of Summer (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 110.

2 Telephone interview with Don Schwall, November 2, 2013. Unless otherwise noted, all of the quotes attributed to Schwall come from this interview.

3 Larry Clafin. “Slab Ace Schwall Chucked Cage Career,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1962, 9.

4Associated Press. The New York Times, December 10, 1957.

5 Sports Illustrated, April 11, 1960: 79.

6 Curt Smith. Mercy! A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2012), 74.

7 ____., 70.

8 ____. Our House: A Tribute to Fenway Park (Chicago: Masters Press, 1993), xiii.

9 _____. Mercy!, 70.

10 Hy Hurwitz.“Hub Fans Hailing Frosh Hill Dazzler Schwall,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1961: 6.

11 Sports Illustrated, April 11, 1961: 85.

12 Les Biederman. “Schwall Made Roundabout Trip,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1963: 16.

13 ____. “Schwall Pumps New Blood as Pirate Fireman.” The Sporting News, August 21,

1965.

14 Curt Smith. Storied Stadiums: Baseball’s History Through Its Ballparks (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001), 321.

Full Name

Donald Bernard Schwall

Born

March 2, 1936 at Wilkes-Barre, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.