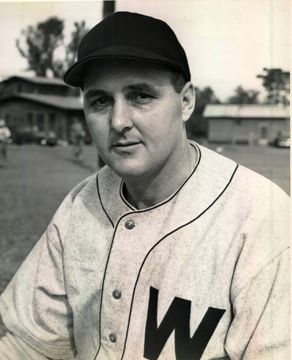

Dutch Leonard

Dutch Leonard rode his knuckleball to a 20-year big league career, baffling batters, catchers, and umpires until he was 44 years old.  As Jackie Robinson described Leonard’s knuckler, “It comes up, makes a face at you, then runs away.”1

As Jackie Robinson described Leonard’s knuckler, “It comes up, makes a face at you, then runs away.”1

Emil John Leonard was born on March 25, 1909, in Auburn, Illinois, the first of five children of Emil and Julia Leonard.2His parents were not Dutch, but immigrants from Belgium.Leonard was nicknamed after an earlier pitcher called Dutch Leonard, who wasn’t Dutch, either. (Crime writer Elmore Leonard said he got the nickname Dutch from the knuckleball pitcher, who was famous when Elmore was in high school.)

Auburn’s high school had no baseball team, but Emil was a star in football and basketball. He pitched in sandlot and semipro games, showing a good fastball. He injured his right (throwing) shoulder in a basketball game.Driving for a layup in the cramped gym, he was knocked into the brick wall behind the basket. His fastball never recovered.

His father, a coal miner,urged his son to look for a better way to make a living. After three days in the mine, Emil decided father knew best. He hitchhiked to Chicago, moved in with an aunt, and found work digging ditches for the electric company. Pitching for the company team, he attracted notice from one of the area’s top industrial teams, sponsored by the Evanston News Index. The newspaper hired him to play ball. He pitched the club to the city championship in 1929, defeating the 41-year-old ex-Cub Hippo Jim Vaughn in the title game.

Leonard was already 21 when he began his professional baseball career in 1930. For four seasons he bounced among at least eight minor league clubs. He was enjoying his best year with Decatur in the Class B Three-I League in 1932, but the team folded in mid-season as the Depression sapped attendance. He went home and got a job driving a truck. The next spring he hooked on with York in theClass A New York-Penn League. His record was just 12-15 for the last-place club in August 1933 when the Dodgers paid York $800 for a 10-day trial.

His major league debut came on August 31 after the St. Louis Cardinals blitzed Dodgers starter Van Mungo for six runs in the first inning. The rookie had been sitting in the bullpen watching the Cardinals hammer the best fastball he had ever seen, wondering how he could possibly hope to get big league hitters out. He relieved Mungo with two out and the bases loaded in the first and held the Cardinals scoreless until the seventh, when they poured on four more runs.

Manager Max Carey had seen enough to keep him. Coach Otto Miller watched him throwing a knuckleball on the sidelines, a pitch he seldom used in competition, and advised him to make it part of his arsenal. In 10 appearances, including three starts, Leonard compiled a 2.93 ERA and a 2-3 record. Both his victories came against the first-place Giants, though after they had clinched the pennant.

The Dodgers were past the days when they were loveable losers known as the Daffiness Boys. They were still losers, but no longer loveable. Leonard was assigned to room with the faded star Hack Wilson. Wilson had set National League records for home runs and RBI, but now he was busy drinking himself to an early death. One night he demanded that the rookie join him for a beer, then slapped the bottle out of Leonard’s hand, sobbing, and told him to stay away from the booze so he wouldn’t end up like Hack Wilson.

Leonard opened the 1934 season in the starting rotation. He shut out Philadelphia in his first start, but lost his next six decisions. Starting and relieving, he finished 14-11 with a better-than-average 3.28 ERA for the sixth-place club. During the season he married 21-year-old Rose Dolene, whose family lived a block away from the Leonard home in Auburn.

For the next two years Leonard worked primarily in relief. He complained that the Dodgers’ catchers wouldn’t call for his knuckleball, leaving him with an assortment of hittable pitches. He led the NL with eight saves in 1935, but nobody knew that because the statistic did not yet exist. His 2-9 record marked him as a failure. In 1936 he was used mostly as a mop-up man in games that were already lost. The club’s new catcher, Babe Phelps, was more hitter than catcher and wanted nothing to do with the knuckleball. He told manager Casey Stengel it was too hard to handle. Stengel barked, “Don’t you think it might be a little hard to hit, too?”3 Phelps led the Dodgers that season with a .367 batting average, so Stengel needed him more than he needed a mop-up reliever. Leonard was sent down to Atlanta in the Class A-1 Southern Association.

Joining the Crackers in June 1936, Leonard met his new catcher, Paul Richards, another washout from the majors. After getting a look at the knuckler, Richards told him, “You keep throwing it, and it’s my job to catch it.” Leonard said, “Richards was the first catcher I ever worked with who wasn’t too timid to call for my knuckleball.”4Leonard went 13-3 with a 2.29 ERA, best in the league, and helped Atlanta win the pennant.

In December the Dodgers traded him to the Cardinals, but his hope for another chance in the majors was quickly snuffed out; two weeks laterthe Cardinals sold him to Atlanta. The next year he was 15-8, 3.64, for the Crackers, despite missing two months because of a kidney stone. Leonard always credited Paul Richards with turning his career around: “He put me back in the big leagues after Brooklyn let me go.”5 Richards went on to a long career as a manager and general manager with a reputation for transforming losing pitchers into winners.

The Washington Senators drafted Leonard after the 1937 season, paying Atlanta $7,500 for a castoff who was approaching his 29th birthday. Washington owner Clark Griffith said he was confident his catcher, Rick Ferrell, could deal with the knuckleball. The pitch had always been an oddity since it was introduced early in the 20th century. Some pitchers used it occasionally as a change-up or surprise pitch, but few—notably Jesse Haines, Eddie Rommel, Fred Fitzsimmons, and Ted Lyons—had made it their trademark. The knuckler is hard to hit and hard to catch, but also hard to throw, since the pitcher has to deliver it with little or no spin. Even a slight breeze at the pitcher’s back can turn a knuckleball into a nothing ball. As Leonard said, “That knuckler can be either a pitcher’s meat or his poison depending on how it’s working.”6

Leonard gripped the ball with the tips of his index and middle fingers. He said, “I just throw it straight forward like you’d flip a cigarette butt.”7He threw with different arm angles so the pitch moved up, down, or sideways. He stuck with the knuckler unless he fell behind in the count, when he had to rely onhis sort-of fastball or slow curve. What distinguished Leonard from most of his tribe was his excellent control. Although he said he never knew exactly where the pitch was going, he usually walked no more than two batters per nine innings in his prime. But he realized he was balancing on the edge with every pitch: “The trouble with the knuckle ball is that the .250 hitters are just as apt to hit it safe as the .350 hitters. None of them will hit the knuckler if it’s breaking right and all of them will hit it if it isn’t breaking.”8

Shortly after Leonard joined Washington in 1938, sportswriter Robert Ruark described him as “a fat bald man.”9He was six feet tall and topped 200 pounds. In his first start he shut out the Athletics. On May 4 he faced Cleveland’s 19-year-old phenom, Bob Feller. The league’s fastest pitcher and its slowest matched zeroes for 10 innings. Feller was relieved, but Leonard kept knuckling until the Senators won in the 13th.

He had secured a regular starting job for the first time in his career. In 1939 he won 20, lost 8, for a sixth-place club that recorded only 65 victories. He was the Senators’ first 20-game winner since their pennant season of 1933. He made the All-Star team in 1940, despite leading the league with 19 losses, then bounced back with 18 wins in ’41, all the while with a losing club.

Leonard’s first four seasons in Washington were nearly identical, with ERAs around 3.50 and about two walks and three strikeouts per game. Because he struck out few batters, he was more dependent on his defense than the average pitcher. His fluctuating won-loss records reflect the quality of the Senators’ fielders as well as the whims of luck. In his 18-13 year in 1941, he was the league’s best in fieldingindependent pitching, a statistic that measures a pitcher’s performance without regard to the fielders behind him.

His 1942 season ended in his second start, when he was hustling to beat out an infield hit and broke his left ankle sliding into first base to dodge a tag. He tried to come back four months later, but couldn’t.

The military draft began taking large numbers of big leaguers in 1943. Leonard was deferred from service because he and Rose had two children (a third came later) and he was supporting his mother and a sister.

He raised his game against weak wartime competition, lowering his ERA in each of the next three years.He started the 1943 All-Star Game at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. The National League’s first two batters, Stan Hack and Billy Herman, singled. Stan Musial’s sacrifice fly brought Hack home. Then Leonard set down eight of the next nine batters (one reached on an error). He finished his three-inning stint with a 3-1 lead, thanks to Bobby Doerr’s homer, and was the winning pitcher. Although he was picked for four All-Star teams, this was his only appearance.

The Senators opened the 1944 season with four knuckleball pitchers. Roger Wolff, Johnny Niggeling, and Mickey Haefner joined Leonard to give 38-year-old Rick Ferrell nightmares. Each knuckler was different. Niggeling gripped the ball with one fingertip. Leonard and Haefner used two, Wolff three. Contrary to legend, Ferrell did not set a record for passed balls in either ’44 or ’45, but he did allow more than anyone since catchers began wearing shinguards. Ferrell compared the knuckleballto a butterfly: “Did you ever try to catch one with your hand? Well, that’s the way it is catching the knuckler.”10 He and the Yankees’ Bill Dickey were the first to use a flexible mitt, rather than the conventional pillow, which allowed them to receive pitches one-handed and protect their bare fingers. Ferrell always wore his full gear when he warmed up his nemeses and said he suffered his only broken finger when he got careless while warming up Leonard.

Niggeling, who had labored in the minors for 10 years, said every knuckleball pitcher owed his career to Leonard and Ferrell: “They made the big leagues change their minds about the knuckle ball.”11 The four flutterballers, plus hard-throwing Early Wynn, couldn’t keep the 1944 Senators out of last place. A roster that included the 40-year-old Niggeling, 17-year-old infielder Eddie Yost, nine Cubans, and a Venezuelan (all draft-exempt) lost 90 games. But their final victory was the one that mattered most.

On October 1 the Detroit Tigers were tied for first place with the St. Louis Browns, needing only to beat the tail-end Senators in their last game to clinch at least a share of the pennant. Leonard was Washington’s starting pitcher. That morning he answered the phone in his hotel room and an anonymous caller told him, “Dutch, I can guarantee you close to $20,000 if you’ll let down against Detroit.” Leonard said, “I promptly told the guy where to go and hung up the phone.” His roommate, George Case, urged him to report the bribe attempt to protect himself. When he went to manager Ossie Bluege, Bluege told him, “You’re still my pitcher.”12

Leonard, who hadn’t beaten the Tigers since 1941, shut them out on two hits through eight innings, facing just 25 batters, one more than the minimum. He gave up a meaningless run in the ninth, when a 41-year-old pinch hitter, Chuck Hostetler, singled and 39-year-old Doc Cramer knocked him in. Such was wartime baseball. Washington won, 4-1. An hour later the Browns beat the Yankees to claim the only pennant in their history.

The story of the attempted bribe didn’t hit the papers for several weeks. When it did, Leonard at first said he thought the phone call was a joke. Later he acknowledged that he believed the caller was serious.

Leonard turned in his best season in 1945, but lost his best chance to pitch in a World Series. The Senators hung on in a close pennant race with the Tigers. Their season ended a week ahead of everyone else, because Clark Griffith had agreed to turn his ballpark over to his tenant, the NFL Redskins. After their last game on September 23, the Senators were just one game behind Detroit. The Tigers beat the Browns on the final day ofthe season to win the flag.

Leonard finished 17-7 with a 2.13 ERA, his career best. He recorded the league’s top strikeout/walk ratio, 2.74. But he came down with a sore shoulder in September and was little help during the crucial stretch drive. He later said Griffith blamed him for losing the pennant and cut his salary.

Continuing shoulder and back problems limited his workload in 1946. After he posted a 10-10 record in 23 starts, Griffith sold him to the Philadelphia Phillies. Leonard was shocked that no other AL team had claimed him before he passed through waivers to the National League. The 37-year-old fat bald man looked in the mirror and told Rose he was going on a diet: “no white bread, no starches, no midnight snacks, no beer, no anything except hard work.”

When he joined the Phillies for spring training in 1947, he had reduced his weight from 220 to 185. All spring he ran like he was prepping for a marathon. “I think I ought to have four or five more years in the majors,” he said. “And I know one thing. For the rest of my life, whether or not I’m playing baseball, I’m never going to let myself get fat again.”13 He pitched seven more seasons and became an evangelist for clean living and an hour of running every day.

In his first season with Philadelphia, Leonard was the ace of a club that finished tied for last place. He put up a 17-12 record, and his 2.68 ERA was fourth best in the league. He had the advantage of surprise. Few National League hitters had ever seen a good knuckler; for some reason, or no reason, most successful knuckleballers until then had been in the AL. The next year Leonard was even better at age 39. His 2.51 ERA was second in the league, but his record was reversed, 12-17. He suffered from weak run support and every disaster short of the plague: He was hit on the foot by a line drive, hit in the eye by a bouncing ball, beaned while batting, and his thumb was jammed when he tried to field a bunt barehanded.

After the 1948 season, the Phillies, launching a badly needed youth movement, passed Leonard on to the last-place Cubs, who dragged Leonard down with them. His ERA swelled to 4.15, the highest of his career, with a 7-16 record. He was a victim of leaky defense; his 2.71 fielding-independent pitching mark was the league’s best.

As he passed his 41st birthday during spring training in 1950, Leonard was the oldest player in the National League, and his career was on the line. Instead of dumping him, Cubs manager Frankie Frisch made him a reliever. Frisch acknowledged that the knuckler was risky in tight spots with runners on, but said, “He has control, he’s always in good condition and always willing to pitch.”14

The bullpen was still seen as a place for second-class pitchers, but the demotion bought Leonard another four years in the majors. In 1951 he put up a 10-6 record with a 2.64 ERA. He made his only National League All-Star team, but did not appear in the game. In a late-September game he pitched to the Cubs’ bonus-baby catcher, 18-year-old Harry Chiti. He had played against Chiti’s father in semipro ball before Harry was born.

The next year he shrank his ERA to 2.16 and saved 11 games (calculated years later). OnJuly 5, 1953, the Cubs staged Dutch Leonard Day at Wrigley Field. Fans presented him with an air-conditioned Cadillac. But his ERA jumped to 4.60, and the Cubs released him at the end of the season. After 24 years in pro ball, his career ended at age 44with a 191-181 major league record and 3.25 ERA.

The Cubs made Leonard their pitching coach under manager Stan Hack. He stayed in the role for three years, while the team was going nowhere. After a last-place finish in 1956, the Cubs fired their general manager, manager, and all the coaches.

By that time the knuckleball torch had passed to Hoyt Wilhelm, who joined the Giants in 1952 and led the NL in ERA. Wilhelm had learned the knuckler after he saw a photo of Dutch Leonard’s grip, although he threw it harder than Leonard. The pitch began to die out in the ‘60s when pitching coaches, most of whom knew as much about throwing a knuckler as they did about throwing a discus, preached that only full-time knuckleballers could master it.

Leonard started a new career as a counselor with the Illinois Youth Commission, a state agency whose mission was to prevent juvenile delinquency and rehabilitate young offenders. His job consisted of conducting baseball clinics around the state, sometimes four a day for hundreds of boys. He pitched until “everybody gets to hit.” He began wearing a jersey with the logos of every big league team he had played for; he said it saved answering questions. Leonard turned down professional coaching offers and worked with young boysuntil he retired at 65. He said, “If I can help just one kid go straight my job is worthwhile.”15

Dutch Leonard died of congestive heart failure at 74 on April 17, 1983. He was survived by Rose, his wife for nearly 49 years, sons Tom and Dan, and daughter Judy.

“Baseball was my life and I loved every minute of it,” he once told a writer. “It was fun, not work, to me.”16

Additional source

Dutch Leonard, as told to Stanley Frank, “Too Old to Pitch? Don’t Make Me Laugh.” Saturday Evening Post, July 4, 1953.

Notes

1The Sporting News, November 12, 1947, 11.

2 The son’s name is spelled “Amial” in the 1910 census records, while his father’s is spelled “Ammial.”

3 Robert Creamer, Stengel: His Life and Times (repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996),187.

4The Sporting News, October 1, 1942, 2.

5Washington Post, April 6, 1940, 17.

6Ibid., June 6, 1944, 16.

7 Associated Press-Brooklyn Eagle, July 16, 1939, in Leonard’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

8Washington Post, June 6, 1944, 16.

9New York World-Telegram and Sun, April 14, 1953, in HOF file.

10The Sporting News, May 26, 1938, 3.

11Washington Post, April 18, 1944, 12.

12The Sporting News, March 12, 1966, 23.

13Ibid., May 28, 1947, 5.

14Ibid., April 12, 1950, 19.

15Ibid., March 12, 1966, 23.

16Ibid.

Full Name

Emil John Leonard

Born

March 25, 1909 at Auburn, IL (USA)

Died

April 17, 1983 at Springfield, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.