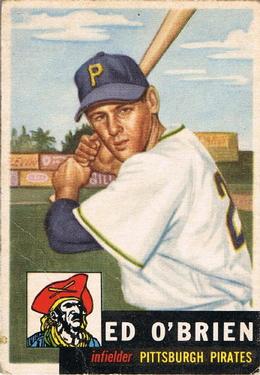

Eddie O’Brien

In 1969 the expansion Seattle Pilots hired Eddie O’Brien as bullpen coach. His role was to assist manager Joe Schultz and pitching coach Sal Maglie. Asked at the start of the season to specifically describe his duties, O’Brien offered “Well, I look in to Sal or Joe, and they let me know when I’m supposed to get a pitcher ready.” Asked how he would know if a pitcher was ready, he replied with a grin. “They tell me.”1

In 1969 the expansion Seattle Pilots hired Eddie O’Brien as bullpen coach. His role was to assist manager Joe Schultz and pitching coach Sal Maglie. Asked at the start of the season to specifically describe his duties, O’Brien offered “Well, I look in to Sal or Joe, and they let me know when I’m supposed to get a pitcher ready.” Asked how he would know if a pitcher was ready, he replied with a grin. “They tell me.”1

Eddie O’Brien is immortalized as “Mr. Small Stuff” in Ball Four, the ground-breaking work by pitcher Jim Bouton recounting the travails of his 1969 season.2 Bouton depicted O’Brien as a clueless minion who refuses to warm up the knuckleballing hurler and obsesses over trivialities. The appointment was a goodwill gesture and public-relations move by club management.3 It also gave Eddie the necessary service time to qualify for a major-league pension.4 At the time, a cumulative four years of major-league service (player, coach, manager) was required to qualify for a pension.

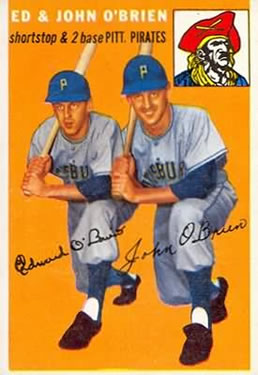

Despite Bouton’s unflattering portrait, O’Brien enjoyed iconic status in Seattle until his death in 2014. He and his identical twin brother, Johnny, were legendary collegiate athletes and coveted major-league prospects. After brief pro baseball careers, both returned to the Pacific Northwest and contributed to civic life.

Edward Joseph O’Brien and his brother were born on December 11, 1930, in South Amboy, New Jersey, the eldest of Edward James and Margaret (Smith) O’Brien’s five children. Their father, a native of South Amboy, was employed as a deckhand by the Pennsylvania Railroad. The boys and their siblings grew up in a tiny, two-bedroom apartment. Neither parent lived past middle age. Their mother died in 1950; their father succumbed in 1955.

In 1948 the O’Briens graduated from St. Mary’s High School in South Amboy, an Irish-Catholic enclave on the banks of Raritan Bay. Eddie was primarily a center fielder and exhibited a strong throwing arm. Johnny played the infield. Both were right-handed batsmen. The catcher on their high-school team was Jack McKeon, who would gain prominence as a big-league manager and general manager decades later. The school also produced Tom Kelly, manager of the Minnesota Twins from 1986 through 2001. An earlier alumnus of St. Mary’s was Allie Clark, a major-league outfielder from 1947 to 1953.

“Wherever they went, they had a baseball glove on,” Clark recalled about the 5-foot-9-inch twins. “If it was winter, they had a basketball.”5 Despite their modest size, they were two-sport stars. In March of their senior year, Eddie was chosen for second team and Johnny the first team on the Middlesex All-County basketball squad.6 That summer, they helped lead the South Amboy All-Stars to the New Jersey state championship and a berth in the All-American Amateur Baseball Association tournament in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Although South Amboy bowed out in five games, Eddie batted .500 and clubbed two home runs among 11 hits.

The twins needed scholarships to attend college, and were determined to enroll together. Tryouts at Seton Hall and Columbia Universities proved fruitless. The Brooklyn Dodgers, under general manager Branch Rickey, offered to pay their way to attend St. John’s University if they signed with the Dodgers and forfeited their collegiate sports eligibility.7 The O’Briens stayed in South Amboy that winter and played amateur baseball in 1949. While competing at the National Semi-Pro Baseball tournament in Wichita in August, they caught the eye of Al Brightman, the first baseman on a rival team from Washington State. Brightman was also the baseball and basketball coach at Seattle University, a small independent Division I school with an undistinguished athletic program. After the tournament, Brightman secured scholarships for the twins to attend the Jesuit institution and compete in both sports.

The freshmen made an immediate impact. “O’Brien Boys Are Pitchers’ Scourge,” wrote sportswriter Jack McLavey in 1950. “Seattle University’s popular twin-brother act, John and Ed O’Brien, kept their basketball opponents in a dither last winter [and] are treating rival baseball pitchers in the same ungentlemanly fashion.”8 Eddie posted a .341 batting average that season. His sophomore and junior years were even better. In 1951 he compiled a .393 average and .607 slugging percentage. In a game against Seattle Pacific College, the center fielder hit two inside-the-park home runs and a triple, and drove in nine runs. In 1952 Eddie hit .431 and slugged .794. His nine round-trippers broke the single-season school record of eight set by his brother the previous year. The fleet-footed leadoff hitter stole 17 bases.9 Johnny’s production during this period was similarly robust. Over three seasons, the duo led the Chieftains’10 baseball program to a 61-14 won-lost record and a berth in the 1952 National Collegiate Athletic Association tournament.

Their exploits on the basketball court were equally sensational. They adopted a fast-paced style of play to take advantage of their speed and neutralize their height disadvantage. “Eddie-O” was the playmaker, “Johnny-O” the prolific scorer. On December 22, 1952, Eddie uncharacteristically outscored his brother 33 to 29 in a 102-101 win over New York University at Madison Square Garden. In the era before a mandatory shot clock, it was the first collegiate game in which both teams scored over 100 points. Perhaps their most impressive performance came on January 21, 1952, when they led the Chieftains to an 84-81 upset victory over the much taller Harlem Globetrotters. The tandem led the varsity hoopsters to a 90-17 record and appearances in the 1952 National Invitational Tournament and 1953 NCAA Tournament.11

During this period, Branch Rickey’s interest in the O’Briens intensified. The Mahatma had left Brooklyn and was general manager of the cellar-dwelling Pittsburgh Pirates. In May 1952 a sportswriter reported that the twins would likely pass up their senior year of collegiate baseball eligibility to sign with the Corsairs.12 That summer, they worked out before Rickey at Forbes Field. Seven other major league clubs were also in pursuit. The Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League saw the hometown heroes as a prime gate attraction and were serious bidders.

There was disagreement among scouts over which of the twins had more potential, and conjecture that some clubs wanted to sign only one, not both. “No, that isn’t true,” Eddie said later. “We both had offers from the same clubs. No one spoke to us about only one of us signing.”13 Rickey enlisted the help of minority club owner Bing Crosby to woo the O’Briens to Pittsburgh. “He’d send us Christmas gifts every year,” Eddie remembered of the popular entertainer. “He was a close friend until the day he died.”14

On March 19, 1953, Pittsburgh announced that scout Ed McCarrick had signed the brothers to contracts calling for bonuses of $40,000 each.15 Other reports pegged the O’Brien bonuses at between $15,00016 and $45,000.17 The actual amount was $25,000 each, and included their first- year major-league salary of $6,000.18 The twins used the funds to buy their father a house and a new car.

Under the major-league bonus rule in effect at the time, the O’Briens would have to be retained on the Pirates’ active roster for at least two years.19 The bonus rule, which was approved at the winter meetings during the first week of December 1952 and in effect through 1957, mandated that players signed for bonuses of more than $4,000 be kept in the major leagues for two years.

The bonus babies left Seattle immediately and reported to spring training in Havana. Rickey wanted to maximize the novelty of identical twins playing on the same team and informed Eddie that he was to become an infielder. “I have never played in the infield in my life,” the center fielder confessed, “but Mr. Rickey wants Johnny and me to play together so I’ll have to learn.”20 The rookies flew to the Bucs’ minor-league camp at Brunswick, Georgia, to begin the conversion. Eddie was to play shortstop, Johnny second base.

The O’Briens were the first twins in major-league history to play for the same team since Red Shannon and Joe Shannon appeared in one game together in 1915. Manager Fred Haney brought the newbies along slowly. Eddie appeared as a pinch-runner in his first four major-league games, and finally saw action in the field and at the plate in a May 27 doubleheader. He collected his first hit and stolen base off Steve Ridzik, but also made two errors. The same day, he and his brother were ordered to take their US Army physical exams.21 On June 7 the O’Briens appeared together in the starting lineup for the first time. From then until September 2, they were the Pirates’ primary keystone tandem.

The O’Briens were the first twins in major-league history to play for the same team since Red Shannon and Joe Shannon appeared in one game together in 1915. Manager Fred Haney brought the newbies along slowly. Eddie appeared as a pinch-runner in his first four major-league games, and finally saw action in the field and at the plate in a May 27 doubleheader. He collected his first hit and stolen base off Steve Ridzik, but also made two errors. The same day, he and his brother were ordered to take their US Army physical exams.21 On June 7 the O’Briens appeared together in the starting lineup for the first time. From then until September 2, they were the Pirates’ primary keystone tandem.

Haney was generous in his assessment of the youngsters. “The O’Brien kids have done a fine job defensively. In a couple of years, they should be finished ball players, but the Army probably will interrupt before that time.”22 As the season progressed, local sportswriters were not as kind. “The O’Briens were handling the key infield spots and the Pirates were going down with disgusting regularity,” wrote one. “Both started kicking the ball around, couldn’t hold throws and were out of position on numerous occasions.”23 All told, Eddie committed 23 errors at shortstop in 81 games. At the plate, he averaged .238 with five doubles, three triples, and an on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) of .569 in his rookie year.

On September 10, 1953, the O’Briens were inducted into the Army and assigned to the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. “John and I didn’t play [baseball] at all in the service,” Eddie lamented. “They didn’t have a team at Aberdeen [at least then24], and most of the time if we wanted to work out we had to do it ourselves.”25 The twins returned to the hardwood for competitive action. In March 1954, they led the Aberdeen base cagers to victory in the Second Army basketball tournament.26 On June 26 of the same year, Eddie married Patricia McGough, a Seattle U. Homecoming Princess, to whom he had become engaged the previous Christmas.

Eddie and his brother were discharged from the Army on June 10, 1955. Since military service time was excluded from the bonus rule, they returned to the Pirates’ active roster. Dick Groat, the former Duke basketball star, had firmly grasped the starting shortstop position that spring following two years of military service. After several weeks of utility play, manager Haney inserted Eddie into the starting lineup. From July 17 until the end of the season, he was the team’s leadoff hitter and center fielder. The fly chaser fielded much better at his former collegiate position than he did at shortstop. In 56 games he made just one error and recorded nine assists. But his hitting was anemic. Eddie finished the 1955 season with a .233 batting average, three doubles, one triple, and a .544 OPS. This level of production was inadequate, especially at a position that featured Willie Mays, Duke Snider, and Richie Ashburn among the Bucs’ National League rivals.

In the fall, the O’Briens returned to Seattle to complete their college degrees. In the wake of their father’s death earlier in the year, the twins moved their young siblings from New Jersey to Washington State so the family could be together. Eddie also coached the Seattle University freshman basketball team.

On February 27, 1956, O’Brien departed for the Pirates spring-training camp. Fiery Bobby Bragan had replaced the congenial Haney as manager of the Pirates. At the conclusion of spring training, a reporter asked the skipper if he had any disappointments. “Yes,” Bragan replied candidly. “I just wish that Eddie O’Brien had played the infield in college. He would be that much more advanced. He isn’t big enough, nor does he have the power, to play in the outfield.”27 Unfortunately, the bonus rule prohibited the O’Briens from being sent to the minors to gain playing time until midseason. Pittsburgh solved its center-field problem in May by trading for 1955 Rookie of the Year Bill Virdon.

The bonus designation for the O’Briens terminated on July 2, and the Pirates attempted to farm them out. The Braves, managed by Haney, put in a waiver claim, and the move was withdrawn.28 Eddie appeared in only 63 games, mostly as a pinch-runner, and came to bat just 58 times. He played sparingly at six different positions in the field. On July 31 he made his mound debut. Eddie and his brother each pitched two scoreless innings of mop-up relief. “I am not so sure their future in the big leagues isn’t on the mound,” Bragan mused afterward.29 Both were described as having a herky-jerky delivery and sharp control.30

Eddie and Patricia returned to Seattle after the season. The couple started building a house in the Seattle suburbs. By this time, they had started a family. Edward Joseph Jr. was born in July of 1955. Peggy came along the following year.

On January 19, 1957, the O’Briens signed new contracts with Pittsburgh, succeeding their initial bonus agreements from 1953. One month later, Eddie hitched a trailer to his station wagon and drove nine days with his wife and children from Seattle to the Pirates’ spring training camp in Fort Myers, Florida. His status with the club was precarious. The 26-year-old was no longer guaranteed a major-league roster spot previously secured under the bonus rule. Furthermore, Pittsburgh signed a new bonus baby, USC shortstop Buddy Pritchard, to its big-league roster on February 7. In late March the Pirates again attempted to waive the O’Briens to the minor leagues. Eddie cleared waivers; Johnny did not. “John and I had an emotional parting in Fort Myers,” the demoted utilityman confided. “In this business, there is no room for sentiment.”31

Eddie was assigned to Hollywood of the open-classification PCL on a 24-hour recall, necessitating a second transcontinental trip with his family. “This was a rugged grind,” Eddie recalled. “Ever tour the country with two babies in a station wagon?” But the optimist was not complaining. “I would rather play in Hollywood than sit on the bench in Pittsburgh.32

His wish was granted immediately. The starting shortstop for the Stars, three-year incumbent Dick Smith, suffered a fractured jaw in the first game of the season.33 O’Brien was given the everyday job, but could not hold it and was benched as soon as Smith became healthy. He played in 20 games at shortstop, pitched once, and batted a mere .158. On May 23 Pittsburgh reassigned him to its International League affiliate in Columbus, Ohio. For the third time in four months, the family piled into the station wagon to make the cross-country auto trek. Upon arrival, a sportswriter asked the versatile utilityman to name his favorite position on the diamond. “Wherever I can play every day,” Eddie replied.34

A second chance for O’Brien to prove himself arose on June 2 in his first game with the Jets, Shortstop Dick Barone was hit by a pitch that broke his hand. Subbing for Barone, O’Brien made the most of his opportunity. In his first 100 at-bats as a Jet, the former bonus baby tallied 36 hits and was named Jet Player of the Month in June. He collected six hits vs. Toronto in a June 9 doubleheader, including his first home run in Organized Baseball, off Ross Grimsley Sr. One week later in a twin bill against Buffalo, he reprised the six-hit performance and hit his second home run, a grand slam off journeyman Glenn Cox.

On June 20 O’Brien laid down a walk-off suicide-squeeze bunt in a win over Rochester. His offensive production cooled as the season wore on, but Eddie was still named to the league all-star team in August.35 In a season-ending poll, league managers chose him as the infielder with the best throwing arm.36 O’Brien appeared in 71 games at shortstop and six games at third base. He averaged .276 with 15 doubles, a triple, 3 home runs, and a .683 OPS.

O’Brien also pitched in nine games. The Pittsburgh organization apparently felt that he was no longer a major-league prospect in the field. “Eddie has great desire and fine aptitude,” said Joe L. Brown, Rickey’s successor as Pirates general manager. “He could develop into a fine shortstop. The trouble is that he probably wouldn’t hit enough.”37 “Eddie isn’t sold on that,” countered one reporter, “but the Pirates are his employer, and he’ll go along with their project, although admittedly against it.”38

O’Brien made his Jets mound debut on July 31, and followed with six more relief appearances. His first start came on August 31 in Havana. Eddie threw a complete-game 7-3 win over the Sugar Kings. The right-hander was described as “firing an explosive fast ball, effective sliders and occasional change-ups.39 He was knocked out of his final start on September 7. His pitching line for Columbus was a 2-0 won-lost record and 3.97 earned-run average over 34 innings.

Eddie was recalled on September 9 and rejoined his brother on the Pirates’ roster. Five days later, he hurled a complete-game 3-1 victory in the first game of a doubleheader at Wrigley Field, allowing six hits and fanning eight Cubs batters. Eddie earned the family bragging rights that day, as Johnny was the losing pitcher in the second game. Eddie pitched twice more in relief, finishing the season with a 2.19 ERA over 12⅓ innings, with 10 strikeouts.

Entering 1958, O’Brien was one of 20 pitchers on the Bucs’ 40-man roster. In an intrasquad game on March 2, he surrendered 11 runs in just two innings.40 Despite a lackluster spring training, O’Brien made the Opening Day roster. On April 19 he gave up three runs in two innings in relief against the Reds. Four days later, the Pirates optioned him to their Pacific Coast League club in Salt Lake City.

O’Brien made his first appearance with the Bees on April 26 in his hometown of Seattle. He suffered a 4-1 defeat to the Rainiers. The right-hander picked up his first win on May 3 against Vancouver. He victimized the Mounties again on July 27 with a three-hit shutout, and whitewashed Seattle on August 6 to gain a measure of revenge. His final appearance, on September 3, was a near-perfect postscript to a once-promising career. The former bonus baby pitched seven innings to earn a 5-2 victory, and was a perfect 3-for-3 at the plate, with a stolen base and two runs scored.

For the season, O’Brien fashioned a 9-11 won-lost record and 4.35 ERA. The versatile hurler started 15 games and relieved in 21 others, several of which were in high-leverage save-type situations. He pitched 147 innings for the Bees, second-most on the club, and posted a .305 average in 59 at-bats.

The Pirates intended to recall O’Brien after the end of the PCL season.41 On September 4, word leaked out that he had accepted an offer to become athletic director at Seattle University. The appointment was confirmed the next day. His annual salary at Seattle U. was rumored to be $10,000, likely a significant increase over his pay in the minor leagues.42 “The Pirates wanted me to pitch,” the soon-to-be 28-year-old explained. “Old hands will tell you that when you’re a pitcher, it may take two or three years to get back to the majors. I thought it was time to look around for something so my family could be together where we want to be, in Seattle. As things stand right now, I am through with baseball.”43 Later, Eddie demurred. “If I were to play for anybody, it would have to be for Seattle.”44

Seattle Rainiers general manager Dewey Soriano coveted the O’Brien twins as a potential drawing card. He had tried to purchase their contracts from Pittsburgh for years, but was repeatedly rebuffed. On October 14, 1958, Soriano finally obtained Eddie in a trade for minor-league outfielder Edward Moore. He expressed confidence that he could reach an agreement with the university that would allow Eddie to play.45 But reuniting the O’Briens in Seattle was not to be. “I talked it all out with the school and the club,” Eddie concluded. “Being an athletic director is a full-time job. The Rainiers would want me to play shortstop. You can’t play shortstop without spring training. I couldn’t make that.”46

O’Brien’s final major-league stats include a .236 batting average in 605 plate appearances, 10 doubles, 4 triples, no home runs, and an OPS of .557. He won his only decision as a pitcher and posted a 3.31 ERA over 16⅓ innings.

O’Brien was the Seattle University athletic director from 1958 until 1980, except for a one-year sabbatical in 1969 to join the Seattle Pilots, whose president was none other than Dewey Soriano. Even before that season was over, and well before the club moved to Milwaukee, O’Brien announced that he would not return.47 He coached varsity baseball at the institution for 14 years and compiled a 276-135 won-lost record. He departed when Seattle U. downgraded its programs and dropped out of Division I athletics.

O’Brien began his own public-relations and consulting business. From 1982 to 1984, he was president of Arctic Gulf Marine, an Alaska shipping company, but had no substantive operational tasks. He resigned when the owners of the company became embroiled in a corruption scandal.48 Although O’Brien was never implicated in any malfeasance, the experience was an awkward transition from academia to the private sector.

Over the years, Eddie and his brother remained in the public eye. They were very involved in the Forgotten Children’s Fund, a charity that delivers Christmas gifts to hundreds of families each year, and operated a baseball camp that served 6,000 youths. They hosted the O’Brien Open, an annual golf tournament benefiting athletics at Seattle University, which returned to Division I sports in 2012. In recognition of their contributions to the university, the athletic administration building on campus is named the Ed and John O’Brien Center.49

Eddie and Patricia raised six children. They divorced in 1978. Eddie married Terryl Hackett in 1990. She had three children from a previous marriage. O’Brien died on February 21, 2014, of complications related to Parkinson’s disease. “He was literally the most generous, giving man I know,” asserted stepdaughter Jill of O’Brien.50 “He was five foot, eight and a half inches tall,” brother Johnny eulogized at Eddie’s funeral Mass, “but he lived a seven-foot-seven life.”51

Acknowledgments

Thank you to SABR member Blake Sherry for providing access to the Columbus Metropolitan Library database. Thanks also to Dan Raley, who conducted extensive interviews of the O’Brien family, Kevin Ticen, Dave Eskenazi, and Alan Cohen.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Bill Lamb.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used:

www.legacy.com/obituaries/seattletimes/obituary.aspx?n=eddie-obrien&pid=169880924

Columbus Metropolitan Library, Columbus www.columbuslibrary.org

Seattle Public Library, Seattle www.spl.org

Baseball guides (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1954 through 1959).

Notes

1 Georg N. Meyers, “The Sporting Thing,” Seattle Times, April 21, 1969: 19.

2 Jim Bouton and Leonard Shecter (ed.), Ball Four (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1970), 143.

3 Bill Mullins, Becoming Big League: Seattle, the Pilots, and Stadium Politics (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 102.

4 Meyers.

5 Rick Malwitz, “South Amboy Twins to Be Honored,” Home News Tribune (New Brunswick, New Jersey), February 2, 2003: B1.

6 Gil Geis, “All-County: Sica, Ballou, O’Donnell, O’Brien, Kaskiw,” Sunday Times (New Brunswick, New Jersey), March 14, 1948: 20.

7 Malwitz, “South Amboy Twins to Be Honored”: B5.

8 Jack McLavey, “The Terrible Twins,” Seattle Daily Times, May 19, 1950: 28.

9 Ed Donohoe, “’Get O’Briens,’ B.R. Told Scout Last Year,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1953: 23.

10 Seattle University changed the name of its sports mascot from Chieftains to Redhawks in 2000.

11 Dave Eskenazi and Steve Rudman, “Wayback Machine: Seattle U. Shocks Globetrotters,” http://sportspressnw.com/2124463/2011/wayback-machine-seattle-u-shocks-the-globetrotters.

12 Jack Hewins, “Rickey Keeping Close Eye on O’Brien Twins,” Seattle Sunday Times, May 25, 1952: 39.

13 Jack Hernon, “Twins Rickey’s Hope for New Gate Appeal,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1953: 6.

14 Malwitz, “South Amboy Twins to Be Honored”: B5.

15 Dan McGibbeny, “Bucs Pay $80,000 Bonus for O’Brien Twins,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 20, 1953: 20.

16 Frank Eck, “Bonus Baby Parade to Bushes Due This Season,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1955: 13.

17 Davis J. Walsh, “To Whom It May Concern,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, April 21, 1953: 21.

18 Phone interview with Dan Raley, March 4, 2021.

19 Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953-1957 (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1997), 19-20.

20 Richard Minor, “O’Briens, Janowicz Drill at Bucco Farm Base,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1953: 17.

21 “Major League Flashes,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1953: 21.

22 Hernon, “Four ‘High Aptitude’ Aces on Rickey U. Roster,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1953: 5.

23 Hernon, “Roamin’ Around,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 17, 1953: 19.

24 Another future Seattle Pilot, Gene Brabender, pitched for Aberdeen’s team while in the service in 1964 and 1965.

25 Hernon, “Roamin’ Around,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 29, 1956: 23.

26 “Aberdeen Cagers Win Second Army Basketball Title,” Baltimore Sun, March 20, 1954: 11.

27 Hernon, “Roamin’ Around,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 14, 1956: 15.

28 Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1956: 14.

29 George Kiseda, “Long on Bench as Bucs Nosedive,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, August 1, 1956: 18.

30 The Sporting News, August 8, 1956: 24.

31 Meyers, “The Sporting Thing,” Seattle Daily Times, April 4, 1957: 26.

32 Meyers, “The Sporting Thing,” Seattle Daily Times, April 4, 1957: 26.

33 John B. Old, “Stars Keystone Combine Hurt in Coast Inaugural, The Sporting News, April 17, 1957: 41.

34 Eddie Fisher, “O’Brien Arrives Anxious to Play,” Columbus Dispatch, June 2, 1957: 34B.

35 “Eddie O’Brien All-Star Pick,” Pittsburgh Press, August 13, 1957: 30.

36 Neil MacCarl, “Richmond’s Coates 3-Way Top Pitcher, Say Int. Managers,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1957: 35.

37 Lenny Anderson, “An Old Refrain,” Seattle Daily Times, June 22, 1958: 28.

38 Fisher, “Naranjo, Powers Lead 4-0 Victory,” Columbus Dispatch, August 31, 1957: 8.

39 Fisher, “Homers by Jets Beat Havana,” Columbus Dispatch, September 1, 1957: 21A.

40 Les Biederman, “Thomas Off to Booming Start in Camp Play,” Pittsburgh Press, March 3, 1958: 21.

41 “Pirates Call Up Five Buzzers After PCL Play,” Salt Lake City Tribune, September 3, 1958: 23.

42 John Lindtwed, “Ed O’Brien to Take S.U. Post,” Seattle Times, September 4, 1958: 26; “3-Man Staff to Guide Chiefs,” Seattle Times, September 5, 1958: 21.

43 Meyers, “The Sporting Thing,” Seattle Times, September 11, 1958: 17.

44 “Reidenbaugh Roundup,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1958: 12.

45 Anderson, “Rainiers Land Eddie O’Brien,” Seattle Times, October 14, 1958: 26.

46 Meyers, “The Sporting Thing,” Seattle Times, December 2, 1958: 26.

47 Hy Zimmerman, “Borrowed Shoes Revive Donaldson,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1968: 20.

48 Decisions of the Federal Maritime Commission, Volume 28, July 1985 to June 1987, US Government Printing Office: 800.

49 https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/seattletimes/obituary.aspx?n=eddie-o-brien&pid=169880924.

50 Bud Withers, “Eddie O’Brien of Twins SU fame Dies at 83,” Seattle Times, February 22, 2014: C11.

51 Withers, “Eddie O’Brien, Seattle U Icon, Remembered Fondly,” Seattle Times, March 4, 2014: C4.

Full Name

Edward Joseph O'Brien

Born

December 11, 1930 at South Amboy, NJ (USA)

Died

February 21, 2014 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.