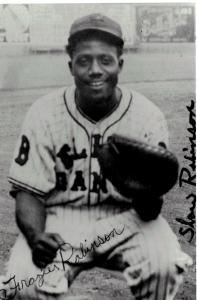

Frazier Robinson

Henry Frazier Robinson was born on May 30, 1910, in Birmingham, Alabama, to the Rev. Henry and Corrine (Black) Robinson.1 The Robinsons had seven children: Edward, Theophilus, Maybelle, John, Estelle, Henry Frazier, and Norman.2

Henry Frazier Robinson was born on May 30, 1910, in Birmingham, Alabama, to the Rev. Henry and Corrine (Black) Robinson.1 The Robinsons had seven children: Edward, Theophilus, Maybelle, John, Estelle, Henry Frazier, and Norman.2

The family moved to Oklahoma City when Frazier was less than a year old to escape the segregation of the South and to start a better life. Claudia Black, Frazier’s maternal grandmother, lived with them and took care of Frazier when he was a baby.3 Claudia was the only grandparent Frazier ever knew and he always heard that she was a freed slave. From what Frazier had been told, his mother and father were both from North Carolina and their parents also had been slaves.4

The family eventually moved to Okmulgee, Oklahoma.5

The elder Robinson, a Protestant minister, was serious about his religion and made sure his family attended church. The children were rarely, if ever, in any trouble at all, according to young Frasier’s autobiography. All seven graduated from Dunbar High School in Okmulgee, and Edward, Maybelle, and Norman all went to Langston University, a historically Black university in Langston, Oklahoma.6

Frazier played baseball for his high school in the spring, and when school was out for the summer, he played for a team in Okmulgee coached by a Catholic priest, Father Bradley. One day the Tulsa Blackballers came to town for a game and the team’s owner, Mr. Lewis, wanted Frazier to join the team. Father Bradley wanted Frazier to attend the Catholic school and play baseball for them. The two coaches argued over Frazier every time the teams played each other. Since playing baseball was his goal in life, Frazier went with the Blackballers and played the 1927 and 1928 seasons with them.7

At age 19, Frazier moved to Akron, Ohio, to live with his oldest brother, Edward, who worked at Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. Edward got Frazier a job there, too. Frazier also played baseball for Goodyear’s company team, the Wingfoot Tigers.8

The Wingfoot Tigers beat almost every team they played and caught the attention of a man named Bullock who wanted to put together a Negro League team in Pittsburgh in 1930. He signed Frazier and four other players from the Wingfoots. While waiting for Bullock’s team to be accepted into the league, they played a few exhibition games. Frazier also attended as many Homestead Grays games as he could. (The Grays were playing in Akron at the time.)

Bullock’s team never materialized, so he cut all the players loose. Instead of staying in Akron, Robinson returned to Oklahoma, where he hooked up with the Abilene Eagles of the Texas-Oklahoma-Louisiana League, a Black league.9 Robinson stayed with Abilene until the league folded, and in 1936 he joined a team in Odessa, Texas.The team was on the road a lot, and Robinson kept a room in Lubbock at Jack Matchett’s father’s house. Matchett and Robinson had played together in Abilene, so they had known each other for a few years. After returning home from a road trip, Matchett’s father handed Robinson a telegram saying that his father had died. It hit Robinson hard, because he always stayed in touch with his parents. He could not make it back in time for the burial, but he did finally get home a few months later.10

In 1939 the Kansas City Monarchs asked Robinson’s brother, Norman, who was three years younger than Frazier, to play for them. The Monarchs needed another catcher, and Norman recommended Frazier.11 Robinson reported to Satchel Paige’s All-Stars, the Monarchs “B” team.12

A team from the House of David was the All-Stars’ first booking of the 1939 season, and the two teams traveled west on a barnstorming tour in which they played against each other. Frazier broke his thumb early in the season and had to return to Texas.

When Frazier Robinson started catching Satchel Paige in 1939, Paige was suffering from an arm injury. After Robinson worked with Paige to get over his injury, Paige told Robinson that he had better be ready because Paige himself was ready. Robinson told him, “Man, I can catch what you’ve been throwing with a work glove.” When the first batter came to bat, Robinson called for a fastball. Paige threw the ball so hard that it knocked the glove off Robinson’s hand and the mask off his face.13

In the spring of 1940, Robinson returned to New Orleans to train with the All-Stars, but his brother Norman did not go with him because he did not like the fact that their manager swore all the time.14 After training camp broke, the All-Stars and Monarchs went their separate ways until a little past midseason, when the bookings between the All-Stars and House of David ran out. Robinson, Paige, and a pitcher named Washington reported to the Monarchs and the rest of the All-Stars were sent home.15

That season Paige gave Robinson the nickname “Slow.” “He said I talked slow and moved around slow so that’s what he called me,” Robinson said.16

After the 1940 season, Robinson went to Baltimore to spend the winter with his brother Norman, who had spent the season with the Baltimore Elite Giants as a utility player and was also a starter for a Baltimore area team, the Sparrows Point Giants. The Sparrows Point team was owned by Dr. Joseph Thomas, who wanted to get his team into the Negro National League.17

Robinson was still under contract with the Monarchs, but he went to the Sparrows Point Giants camp with Norman and made the team. Partway through the 1941 season, Frazier started to catch for the Elite Giants, too. He returned to both the Elites and Sparrows Points Giants for the 1942 season. While in Baltimore, Robinson became a father. His son, Luther, was born to Robinson’s girlfriend, but the couple did not stay together very long.18

In August 1942 the Monarchs came to town to play Sparrows Point and Robinson watched from the stands again. He could not resist the temptation to say hello to his former teammates and met them at their bus after the game. Dizzy Dismukes, who used to pitch for the Monarchs and was now in the front office, asked Robinson if he could be ready to leave on this bus. Dismukes warned him that Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson would blackball him if he was not on the bus when it left. The Monarchs needed Robinson because their catcher, Joe Greene, had hurt his finger and the only backup catcher was manager Frank Duncan.19

Robinson played for the Monarchs over the last month of the season with the Monarchs and a highlight was catching a Satchel Paige no-hitter against a semipro team in Detroit that had been undefeated up until that point. Paige followed up that performance by pitching four innings the next night against the minor-league Toledo Mud Hens.20 In addition to playing in exhibition games, Robinson was 1-for-8 with one run batted in, on August 6 in two league games against the Philadelphia Stars.

The Monarchs were the 1942 Negro American League champions and played the Homestead Grays, champions of the Negro National League in Black baseball’s World Series. Robinson traveled with the team throughout the postseason but did not see any action since the Monarchs’ first-string catcher, Greene, was back from his injury.21

The Monarchs swept the Grays, but Robinson was in no mood to celebrate. During the final game of the series, he was handed a letter from his draft board ordering him to report for induction.22

Although Robinson joined the Navy in 1943, Seamheads shows him as appearing in one game for the Monarchs that year. It was against the Homestead Grays in Wrigley Field on August 29.23 James A. Riley says he made a brief appearance with the New York Black Yankees in 1943 as a reserve catcher and also briefly joined the Baltimore Elite Giants early in the season before joining the Navy.24

Robinson served in the South Pacific and Japan until he received his honorable discharge on October 20, 1945. He went to Baltimore to see his son and the two went to Oklahoma to visit Robinson’s mother.25 He then returned to Baltimore to stay with his brother Norman. After leaving the service, Frazier was not at full strength, so he just worked odd jobs for the winter and spent the evenings going to nightclubs. At one, he met a woman named Catherine whom he married by the end of the year (1945).26

In the spring of 1946, after asking J.L. Wilkinson for his release from the Monarchs, Robinson went to the Baltimore Elite Giants’ training camp, a team that had plenty of catchers, including Roy Campanella. Campanella was not yet that good a catcher, but the manager of the Elite Giants was Biz Mackey, who in his day was known as the best defensive catcher in the Negro Leagues. After converting Campanella into a star backstop, Mackey began to mentor Robinson.27

Buck O’Neil was glad to see that Robinson had found another team. He later wrote the foreword to Robinson’s autobiography in which he asserted, “‘Slow’ had good, quick hands and a strong, accurate arm as a catcher. A quick compact swing with average power as a hitter. Joe Greene was our starting catcher, and I felt that ‘Slow’ had too much to offer as second string. Therefore, I was very pleased when he went to the Elites.”28

Robinson caught the Elites’ pitchers for about half the season, but he was not feeling well. He thought it must have had something to do with being in the hot weather in the South Pacific. Tom Wilson, owner of the Elites, told manager Vernon Green to send him down to the Nashville Black Vols for the rest of the year.29

In 1947 Robinson was back in Baltimore and able to be near his son and play with his brother on the Elites. He caught 42 league games that season as the Elites finished slightly over .500.

Robinson was back with the Elites in 1948 at the age of 38. In 62 games, he hit .182 with 37 hits. Some of the other teams in the league started losing players to the White major leagues and the Elites easily won both halves of the Negro National League season.

The NNL folded after at the 1948 season, and the Negro American League absorbed most of the teams for the 1949 season. Robinson, still with Baltimore, said that this team was the best Elites team he had played for. The season was going well with Robinson catching most of the games until late in the 1948 season, when he slid into third base and his foot went under the bag, snapping his ankle. The injury caused him to miss the playoffs.30

Robinson arrived at the Elites’ training camp in 1950, but his ankle was not healed yet and it took some time before he was ready to play. Once he started playing, he was able to perform well again. Late in the season, the Chicago American Giants were in Baltimore for a series. Chicago was short on catchers, so Giants manager Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe asked Baltimore owner Wilson if they could borrow Robinson for the rest of the season. Powell agreed and Robinson was gone. After the first game, Robinson had a chat with Dr. J.B. Martin, the Giants’ owner, and he found out that Martin wanted to pay him $50 less per month than Radcliffe had promised. After a week in Chicago, th Winnipeg Buffaloes of the semipro Man-Dak League offered Robinson a catching spot and he accepted.31 The Man-Dak league was an integrated league, but Winnipeg was an all-Black team.32

Robinson roomed with future Hall of Fame pitcher Leon Day in Winnipeg. They watched out for each other. “Off the field, Canada was like no place I’d ever been,” said Robinson. He added, “Living and eating conditions were very much nicer. Canada was like paradise.”33

Winnipeg, which finished in second place during the regular season, advanced to the playoffs and played third-place Minot in the first round. Winnipeg came from behind in each of the first two games of the five-game series, and then trounced Minot 13-4 in Game Three to advance. Robinson homered in Game Three.34 In the other first-round series, the regular-season champion Brandon Greys held off the Carman Cardinals three games to two.35

Winnipeg took on Brandon in the best-of-seven league championship. The Buffaloes took the first three games of the series. Brandon took Game Four to set up what turned out to be one of the best pitching duels ever seen in any league. Both pitchers, Leon Day of Winnipeg and Manuel Godinez of Brandon, pitched all 17 innings of the 1-0 Winnipeg victory that crowned the Buffaloes as the 1950 league champions.36 Robinson caught all 17 innings for Winnipeg.37

Robinson was back with the Buffaloes for the 1951 season and hit .318 with a homer and 37 RBIs. On July 28 he connected for three hits, including his lone home run of the season.38

The season did not pass without serious problems for Winnipeg. The Toronto Maple Leafs of the Triple-A International League, a St. Louis Browns farm team, sent a scout to Winnipeg to look at a couple of players. Toronto and St. Louis took five Winnipeg players. Winnipeg’s owner, Stanley Zedd, was so unhappy that he disbanded the franchise at the end of the season.39

Winnipeg did finish the regular season with a 34-29 record, good for second place, three games behind the regular-season champion Brandon Greys. The same four teams from the 1950 playoffs returned for the 1951 postseason. Winnipeg and Brandon each won their first round series to meet for the finals. Brandon swept the four-game series. Robinson hit a home run in Game Four.

When the Winnipeg team folded, Robinson thought it marked the end of his baseball career. He liked Baltimore, but there was no reason to go back there. His apartment had burned down and his wife, Catherine, had initiated divorce proceedings.40 In April 1952 the Brandon team offered him a job. The 42-year-old Robinson joined his brother, Norman, and longtime friend Willie Wells in Brandon for the 1952 season. Brandon finished in last place in the four-team league with a 24-30 record, eight games behind the league-leading Minot Mallards.41 Robinson batted .253 with no homers and 13 RBIs.42

Robinson played the 1952 and 1953 seasons in Brandon and then, at age 43, he called it a career.

Robinson’s brother Edward still lived in Akron, so Robinson settled in nearby Cleveland. He called for his son Luther to come stay with him, but after a few months Luther was homesick for his mother and friends and moved back to Baltimore. Robinson frequented nightclubs, as he had always done, and in 1954, a friend introduced Robinson to Wynolia Griggs. Robinson called her Winnie, and, after dating for a few years, they were married in 1960.43

After retiring from baseball, Robinson’s brother Norman lived in Chicago and he often drove to Cleveland to visit Frazier. Eventually, Norman moved to Los Angeles and worked for A.R.A Services, a provider of food services and merchandise. Norman suffered from stomach pains from a bleeding ulcer, Frazier went to California to visit Norman and decided that his brother needed his help. In 1966 Frazier and Winnie moved to California to take care of Norman.

Norman got his brother a job with A.R.A, but Frazier gave it up and went to work as a Los Angeles school custodian in 1967.44 In 1977 he opened his own business, Sweep it Right Parking Lot Maintenance.45

Robinson and Satchel Paige remained good friends until Paige died in 1982, and Paige visited the Robinsons in both Cleveland and California.46 Robinson was an honorary pallbearer at Paige’s funeral.47

Winnie’s family was from Kings Mountain, North Carolina, and, after Norman died in 1984, the Robinsons moved to Kings Mountain in 1988.48

During All-Star week in Baltimore in 1993, the Upper Deck baseball card company and the Orioles honored members of the Baltimore Elite Giants. Robinson and 25 other Negro American League players were introduced.49

In 1997, in nearby Shelby, North Carolina, the Antioch Missionary Baptist Church was being built and its gymnasium was named after Frazier Robinson because of “the support he has given the church, his ties to athletics, and the grace in which he has carried himself,” said the Reverend James Robinson (no relation).50 When Frazier’s health declined, construction of the gym was accelerated and it was dedicated on October 12, 1997. Among the 350 guests at the dedication was his nephew, Grammy Award-winning singer James Ingram.51 Buck O’Neil said that Robinson had talent as well: “‘Slow’ was a religious person who enjoyed Negro spirituals and sang them very well. He organized a quartet on every team he played on. On the Kansas City Monarchs, it was Satchel Paige, John Markham IV, Barnes, and himself.”52 On the very next day after the gym dedication, Robinson died.53

Robinson’s legacy continued after his death. The Kings Mountain Historical Museum had his artifacts on exhibit in 2002.54 Wynolia kept a special room in their home that contained memorabilia from Robinson’s baseball career.55

Wynolia Robinson died on February 3, 2010. Her funeral was held at the church where the gymnasium was named after her late husband.56

Sources

The author used Baseball-Reference.com and Seamheads.com for stats and team information. In addition, the author relied on Frazier Robinson’s autobiography Catching Dreams, My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues.

Notes

1 Gerald Early, “Introduction: Freedom and Fate, Baseball and Race,” in Frazier Robinson with Paul Bauer, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999), xix.

2 Robinson with Bauer, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues, 2.

3 Robinson with Bauer, 1.

4 Robinson with Bauer, 1.

5 Robinson with Bauer, 2.

6 Robinson with Bauer, 2.

7 Robinson with Bauer, 8.

8 Robinson with Bauer, 9.

9 Robinson with Bauer, 13.

10 Robinson with Bauer, 18-19.

11 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period 1924-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 1998), 85.

12 Robinson with Bauer, 21.

13 Kelley, 85.

14 Robinson with Bauer, 51.

15 Robinson with Bauer, 53.

16 Richard Walker, “For the Love of the Game,” Charlotte Observer, July 24, 1993: 100.

17 Robinson with Bauer, 77-78.

18 Robinson with Bauer, 84.

19 Robinson with Bauer, 78-83.

20 Robinson with Bauer, 84

21 Robinson with Bauer, 86.

22 Robinson with Bauer, 97.

23 Email from Gary Ashwill, May 3, 2021.

24 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994), 671.

25 Robinson with Bauer, 103.

26 Robinson with Bauer, 105. Her last name was not mentioned in Robinson’s biography.

27 Robinson with Bauer, 106-108.

28 Buck O’Neil, “Foreword,” in Robinson with Bauer, xi.

29 Robinson with Bauer, 115.

30 Kelley, Voices, 87.

31 Robinson with Bauer, 163-164.

32 Robinson with Bauer, 168.

33 Robinson with Bauer, 167.

34 Barry Swanton, The ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950—1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2009), 19.

35 Swanton, ManDak League, 19.

36 Swanton, ManDak League, 20.

37 Robinson with Bauer, 170-171.

38 Barry Swanton, Black Baseball Players in Canada (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2009, 144.

39 Swanton, ManDak League, 24-25.

40 Robinson with Bauer, 183.

41 Swanton, ManDak League, 29.

42 Swanton, Black Baseball Players, 144.

43 Robinson with Bauer, 183-190

44 Robinson with Bauer, 192-193.

45 Henry Robinson, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum eMuseum, https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/robinsonh.html.

46 Robinson with Bauer, 202.

47 Larry Tye, Satchel (New York: Random House, 2009), 297.

48 Robinson with Bauer, 204.

49 Walker, “For the Love of the Game,” 99.

50 Mark Terrell, “Church Names Gym for Negro Leagues Catcher,” Charlotte Observer, October 12, 1997: 1B, 5B.

51 Associated Press, “Frazier Robinson: Catcher in Negro Leagues,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 18, 1997: 16. See also Robinson with Bauer, 213.

52 Buck O’Neil, “Foreword.”

53 Ancestry.com, “Henry Frazier Robinson in the North Carolina, US, Death Indexes, 1908-2004.

54 Michael Nixon, “Negro League Star Celebrated at Museum,” Charlotte Observer, July 21, 2002: 167.

55 Kamie Champion, “Catching Dreams,” Kings Mountain Herald, June 24, 1999: 15.

56 Wynolia Robinson, Legacy.com. https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/shelbystar/obituary.aspx?n=wynolia-robinson&pid=139663996&fhid=7723.

Full Name

Henry Frazier Robinson

Born

May 30, 1910 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

October 13, 1997 at Kings Mountain, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.