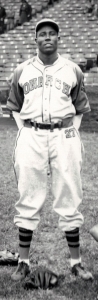

Jack Matchett

Jack Matchett made his debut with the Kansas City Monarchs in Memphis on May 12, 1940; he shut out the Birmingham Black Barons.1 In 1942, when the Monarchs swept the Homestead Grays in the best-of-seven Negro Leagues World Series, Matchett won Games One and Three. The first game was a two-hit shutout.

Jack Matchett made his debut with the Kansas City Monarchs in Memphis on May 12, 1940; he shut out the Birmingham Black Barons.1 In 1942, when the Monarchs swept the Homestead Grays in the best-of-seven Negro Leagues World Series, Matchett won Games One and Three. The first game was a two-hit shutout.

He was one of the “big four” — along with Satchel Paige, Hilton Smith, and Booker McDaniel — a pitching rotation that might well have rivaled any throughout baseball. The Monarchs won Negro American League pennants for five of six years, from 1937 through 1942, save for 1938.

Piecing together the career of most players from the Negro Leagues is a difficult task. So, in some cases, is pinning down the players’ dates of birth and death. All documentation indicates that Clarence “Jack” Matchett was born in Palestine, Texas, as was his father before him. Charlie Matchett (October 10, 1884-August 6, 1968) was a farm laborer, the son of Jane and Sam Matchett, himself a general farm laborer. At the time of the 1910 census, the family unit consisted of four people: Sam Matchett, age 56, his son Charlie, Charlie’s wife, Minnie, and their son, Clarence, age 2. Minnie herself was also listed as a farm laborer. All were natives of Texas. Charlie Matchett served in the United States armed forces during the First World War and was stationed at Camp MacArthur in Texas. He died in Houston.

Unlike his father, Jack Matchett’s actual birthdate is unclear. When he registered for Selective Service in October 1940, he provided his birthdate as February 4, 1907. That date would have made him age 3 at the time of the 1910 census. At the time of registration, he was described as 6-feet-2 and listed at 193 pounds, with black eyes, black hair, and black complexion, and a scar over his right eye.

But when he died, on March 19, 1979, in Los Angeles, two different birthdates were indicated. The California Death Index shows that he was born on January 3, 1905, while the United States Social Security Death Index gives a date of January 3, 1908. A “5” can sometimes look like an “8,” and the 1908 date would conform with the 1910 census.

James A. Riley described Matchett the pitcher: “[T]he right-hander had a free, easy motion and good control of a variety of pitches, including a fastball, screwball, quick-breaking curve, and a very good change of pace. When on the mound nothing seemed to bother him, and his even temperament, hearty determination, and bountiful stamina enabled him to fashion some well-pitched games for the Monarchs.”2 One thing Riley didn’t mention was what Buck Leonard said: “Jack Matchett was an underhand pitcher.”3 Though he pitched right-handed, he batted from the left side.

As to what Jack Matchett did before he joined the Monarchs, aside from a few brief mentions of his playing baseball, there are very few clues. He seems to have moved around 300 miles to the west, to Sweetwater, Texas, and to have been employed baling cotton with compress companies in both Lubbock (another 150 miles farther northwest) and Sweetwater. A May 1938 newspaper article reported him filing a claim for a January arm injury in a door of a press at Lubbock Compress.4 He is named as Jack Matchett of Nolan County; Sweetwater is the county seat of Nolan County. When Matchett registered for the draft in October 1940, he provided an address in Sweetwater and the name of his employer as Western Compress of Sweetwater.

The arm injury may not have been to Matchett’s pitching arm, and/or may not have been serious enough to prevent him from playing baseball. He had apparently begun playing professionally in the early 1930s in the Texas-Oklahoma-Louisiana League, an all-Black league with teams in San Antonio, Dallas, Fort Worth, Tulsa, Waco, Odessa, and Abilene, all in Texas, and one in Louisiana. Catcher Frazier “Slow” Robinson reported playing with the Abilene Eagles in 1930 or 1931 and said, “Our best pitcher was a boy called Jack Matchett.”5

Robinson said, “Matchett was always a cutup,” then added information regarding Matchett’s lack of formal education. “He was a guy who never did go to school. He didn’t have no education. I learned him how to read and write his name.” Robinson also offered a bit about Matchett’s personality: “He was that type of person who figured that whatever he did, he would be right doing it on his own. You know how these people are. If you kind of talk to him or scold him about it, he’d get angry. You’d best serve him with kid gloves. He was that type but he was a good pitcher.”6

Robinson said that he caught for Abilene until the league folded, and then he and Matchett both caught on with a team in Odessa, Texas, in 1936. He recounted a story of playing against a local team in Hobbs, New Mexico, that year. Before the game, the umpire announced over the park’s loudspeaker system, “For the white boys, it’s Ted Blankenship pitching and Beans Minor catching. And for the niggers, it’s a big nigger pitching [Matchett] and a little nigger catching [Robinson.]”7 It wasn’t surprising that the umpire gave Matchett a very small strike zone.

Charlie Matchett had moved to Lubbock and Robinson wrote, “I was on the road most of the time but kept a room in Lubbock, Texas, at Jack Matchett’s father’s house.”8

Matchett may have lived in Lubbock for much of the 1930s. A 1931 city directory shows a Jack and Lula Matchett both at 1711 Av C, with Jack working as a bootblack and Lula as a maid. No marriage record has yet been located, and this may or may not be Jack Matchett the future Monarch. On October 31, 1932, a Jack Matchett married Alberta Brady in Lubbock. The 1937 city directory has him as a laborer at Lubbock Compress Co. Neither a street address nor spouse is mentioned.

In July 1938 Matchett is found in an Odessa newspaper pitching for the Odessa Oilers team. Indeed, “Big Black Jack” threw a 4-0 no-hitter against the Austin Black Senators in a July 7 night game in Midland, striking out 13.9 The catcher in the game was Oilers manager Slow Robinson. Matchett was described as a “combination outfielder and pitcher” and “the new Oiler sensation.” He was 5-for-5 in the game.10

Matchett was with the Black Oilers again in 1939, apparently a popular player and dubbed “The Iron Man” in the April 30 Odessa American. The Oilers were due to play the Mt. Pleasant Black Cubs on May 24, with Matchett on the mound. The article announcing the game said the Cubs had defeated such teams as the Kansas City Monarchs. Matchett beat the Cubs, 3-2.11 The game account introduced another element to Matchett’s story. It asserted that Mt. Pleasant’s starting pitcher, Joe Davis, was Matchett’s half-brother. It said he had been an Oiler and was considering remaining in Odessa and becoming an Oiler once more.

The May 31 American reported that the Kansas City Monarchs were trying to get Matchett for their club.12 He seems to have spent some portion of 1930 playing for Satchel Paige’s All-Stars, a traveling team that was the “B” team of the Monarchs.13 Robinson suggests that it was he who helped bring Matchett and some others to the Monarchs.14

In March 1940 Matchett was still with the Black Oilers, though he spent some time pitching in at least a couple of exhibition games.15

Matchett first shows up in Negro Leagues records in 1940. He was 32 years old at the time. Historian Leslie Heaphy, however, turned up three articles from 1939 that show him pitching for the Monarchs in a couple of exhibition games. In a July 11 game, he worked in relief of Johnny Donaldson in a game in Vancouver, British Columbia, against the local Lowney All-Stars. He walked the first batter he faced, then struck out three in a row to preserve a 6-5 victory.16 Four days later, Satchel Paige pitched the first four innings of a game against the House of David team and Matchett pitched the last five. Each pitcher gave up two hits, and the Monarchs won, 3-0.17 The same two pitchers were slated to pitch in Reno against the House of David.18

Matchett also turned up in a 1940 newspaper, when a dispatch from Marshall, Texas, in the Plaindealer of Kansas City included “Jack Matchett, P, Odessa, Texas” on the 1940 Monarchs roster.19

It was in 1940 that he had his league debut. As noted above, he pitched a shutout against Birmingham in his first game, on May 12. It was a three-hitter, a 6-0 win.20 On the 19th he beat the Memphis Red Sox, 5-3. In several 1940 games reported in the Kansas City Star, Matchett relieved. He sometimes started in doubleheaders, and sometimes he did both on the same day — for instance, quelling a rally in the ninth inning of the first game on August 18 at Ruppert Stadium in Kansas City to beat the Toledo Crawfords, 4-2, and then pitching a complete seven-inning second game to beat Toledo again, 4-3. The score had been tied, 3-3, after 6½. Matchett led off the bottom of the inning with a triple to right-center. After a base on balls, Jesse Warren singled in Matchett with the winning run. James Riley writes that Matchett’s record in 1940 was 6-0 in league play.21

Coverage of the 1941 season is spotty, but Matchett turns up with the team in a few newspaper stories. In June he outpitched Peanuts Nyasses of the Ethiopian Clowns, 1-0, in a four-hitter at Crosley Field.22 The team made its way to the West Coast in July, and Matchett, a “big black boy with a hard one that sizzled,” beat the Medford (Oregon) Craters, 5-4. He struck out 10. His single in the ninth inning won the game for the Monarchs.”23

Portland’s Oregonian lists Matchett as one of the pitchers who might take on the House of David team at Portland’s Vaughn Street ballpark in a July 22 night game, a contest featuring two of the top barnstorming teams of the day.24 The game drew 8,000 fans and resulted in an 8-4 Monarchs win featuring the “superb chucking of Jack Matchett, husky colored ace of the Monarch squad.” He allowed seven hits and struck out 10.25 He appears to have spent most of the year as part of Satchel Paige’s All-Stars.26

As to what Matchett did throughout 1941, information has so far proved elusive.

As the April 25 Detroit Tribune story indicates, the “top-notch” Matchett seemed to have started 1942 with the Cincinnati Clowns. The March 28 Chicago Defender announced that he had indeed signed with the national semipro champion Clowns.27 By the time of the Monarchs’ home opener, however, he was with Kansas City. Norris Phillips was released and Matchett added, the announcement made on Opening Day.28

In the home opener, Matchett kicked off the season with a five-hit, 7-0 shutout against Memphis on May 17. He was 2-for-4 at the plate with a single and a double and scored one of the Monarchs’ runs. Satchel Paige pitched the second game, losing to Memphis, 4-1.29

At the end of May, Matchett worked the second game of a May 30 doubleheader against the Chicago American Giants and then was called on to get the final three outs of the first game against Birmingham on May 31.

On July 5 he started both games of a doubleheader in Birmingham, throwing the first 2⅓ innings in a 10-5 first-game win (relieved by Booker McDaniel), and then pitching all six innings of a complete-game seven-inning 2-1 loss.

Matchett was known to speak up at times and had been ejected from the June 17 game against the Baltimore Elite Giants. He “waved to the dugout after a prolonged argument with Umpire Frank McCrary over a called strike.”30

At the end of July, Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson declared that there were at least 25 Negro League players who were of major-league caliber. He didn’t name them all, but the Associated Press story mentioned “Jack Matchett, 28-year-old Kansas City pitcher, who sometimes operates from the mound accoutered in full dress ensemble topped by a plug hat.”31 That he sometimes enjoyed dressing up during games is reflected in a Plaindealer story saying he was “popular for his antics on the mound in full dress regalia.”32

There were at least a few games in which Matchett played outfield. In a game against the East Chicago Giants on July 25, he played left field. On August 16 and 17 he played right field in back-to-back games.

On August 3 Matchett threw a three-hit shutout against the Baltimore Elite Giants, winning 3-0 at Baltimore’s Bugle Field.33 On the 25th, he threw a three-hitter against the Chicago American Giants, winning that one, 6-1.

The 1942 Negro World Series between the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League and the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League was the first postseason championship between the pennant winners of two Negro leagues teams since 1927. The series pitted two top teams against each other. The Monarchs, as mentioned, had won five NAL titles and the Homestead Grays had won three consecutive NNL pennants.

Had there been an award for the MVP of the Series, Matchett might well have received it. Game One was held at Griffith Stadium in Washington on September 8. Satchel Paige started and worked the first five innings, allowing just two harmless hits in the fourth. Matchett came in and pitched the final four innings, facing 12 batters and setting every one of them down in order. He struck out two. At the plate, he was 1-for-2 and stole a base. The Monarchs won, 8-0, accumulating a number of runs thanks to six Grays errors. Different scoring conventions applied at the time, and Matchett was awarded the win.

The Monarchs won Game Two in Pittsburgh, 8-4, Hilton Smith the winning pitcher.

Game Three was held at Yankee Stadium on September 13. Once again Paige started. He gave up two runs in the first inning. Willie Simms hit a grand slam in the top of the third for the Monarchs, and Matchett was brought in. Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier wrote that Paige had suffered a stomach ailment.34 Matchett pitched the rest of the game — seven innings, allowing just four hits and one unearned run. The final score was Monarchs 9, Grays 3. The Monarchs were 3-0 in the best-of-seven series and Jack Matchett was 2-0, with 11 innings pitched and no earned runs.

Game Four was played in Kansas City, under protest, because the Grays had brought in players from the Newark Eagles and Philadelphia Stars. With their lineup thus bolstered, the Grays outscored the Monarchs, 4-1, but the next day the game was disallowed. Matchett had left the team to return to Kansas City and rest up for the game, while the Monarchs played a few non-Series games against the Cincinnati Clowns during the week. But Matchett apparently had a bit of a drinking problem at times and was not in condition to start the game.35

Matchett, however, started the next game, the legitimate Game Four, on September 29 at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. Satchel Paige had been due to start, but simply wasn’t there at game time. Not expecting to have to start, Matchett was pressed into action. He was tagged for three runs in the first inning and two more in the third. The Monarchs got one run in each of the same two innings. Paige then arrived, saying he’d been detained and given a traffic ticket in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (some 80 miles away), on his way to the game. With two on and two out in the fourth inning, Matchett was relieved by Paige and the Grays failed to score again while the Monarchs came back with seven unanswered runs to win the game and the World Series.

Perhaps Matchett’s growing reputation had prompted a promotion of sorts in stature, as in 1943 he was often referred to as “Big Jack Matchett” and seen as one of the “big four” in the Monarchs rotation, with Satchel Paige, Hilton Smith, and Booker McDaniel.36 The Monarchs had another very good season, but the Cleveland Buckeyes — playing 10 fewer league games — wound up with a slightly higher winning percentage (38-22 for a .633 winning percentage, while the Monarchs were .614 (43-27).37

Matchett pitched a 1-0 (seven-inning) shutout in the second game of the May 16 Opening Day doubleheader at Ruppert Stadium.38 On May 24 he lost a heartbreaker, pitching all 12 innings of a game lost to the Cleveland Buckeyes in part due to a Monarchs error, 2-1.39 As in every year, he both started and relieved in games. On June 3 he worked the first eight innings of a game against the Chicago American Giants at Comiskey Park and, with his third hit of the game, struck a one-out, bases-loaded single in the ninth inning to drive in two runs and win the game, 4-3.40

Precisely how Matchett fared in the 1943 regular season is difficult to pin down, but when the “Royal Giants” arrived in Long Beach to play a game against Red Ruffing’s All-Stars on October 17, a Long Beach newspaper said he had been 23-5 during the season.41 The San Diego Union wrote five days later that he had been a “27-game winner during the recently completed Negro National League season.”42 That would represent a pretty spectacular season.

World War II was in progress and coverage of Negro League ballgames was perhaps sparser than usual. The NAL opened on May 30, 1943, and Matchett and 18,000 fans flocked to Comiskey Park to see the Monarchs play the Chicago American Giants. Matchett worked eight innings but was facing a 3-2 deficit. In the top of the ninth, the Monarchs hit three singles in succession, a batter struck out, and then Matchett (he was 3-for-4 in the game) singled into center field for two runs, to give Kansas City a 4-3 lead. Paige relieved in the bottom of the ninth and secured the win.43 Matchett pitched a three-hit shutout of Nashville on June 17 in Louisville.

After the 1943 season was complete, Matchett and many of his Monarchs teammates played as Chet Brewer’s Kansas City Royals through the winter in Southern California, playing games in San Diego and Los Angeles in November, December, and January. He appears to have picked up another nickname: Big Train Matchett.44

Matchett also seems to have become a name to be reckoned with: When an advertisement was placed in the San Antonio Light for a May 10, 1944, game against the Memphis Red Sox, the ad read: “Featuring Jack Matchett.”45

He had a successful regular season with the Monarchs in 1944. On September 3 he beat the visiting Memphis Red Sox, 3-1, the one run unearned.46

Matchett apparently was a good hitter. In early June 1944, he was reported as leading the Negro American League with a .471 batting average, four points ahead of Cleveland’s Sam Jethroe.47 A column in the Pittsburgh Courier called him “one of the best hitters on the club.”48 According to the New Orleans Times-Picayune, he had won 10 games before being prepared to pitch for the South team of Negro League All-Stars in an October 1 North-South All-Star game.49

It is worth parenthetically noting that not only did Slow Robinson write “Matchett could hit” but he added, “There were several pitchers that could field their position. Jack Matchett was one of the best.”50

A number of the Monarchs entered military service during the course of the Second World War, but Matchett’s age may have proved an advantage that kept him out of the service. The same “big four” rotation remained through the 1945 season and Frank Duncan continued as manager through the war years. During the 1945 season, the Monarchs added a new infielder during spring training in Houston — Jackie Robinson. Paige, Matchett, and Double Duty Radcliffe were bombed for 12 runs on June 24, and the Monarchs lost both games of a doubleheader against the Grays at Griffith Stadium, as Robinson hit safely seven times in succession.51

Seamheads shows Matchett pitching in only one game, for two innings, though scattered stories throughout the season list him as one of the possible pitchers for given games.

In 1946 the Chicago Sun listed Matchett among the Monarchs pitchers returning for the season, as did the Chicago Tribune on the morning of Opening Day.52 He does not appear in such game accounts as could be found. A pair of stories in June have him pitching for the Abilene Black Eagles against the Fort Worth Black Giants on June 19 and against Waco on July 1. Abilene lost to Waco, 7-4, but Matchett “with triples and a single, paced the Abilene attack.”53

A month later, Matchett pitched for the San Antonio Giants in a July 26 road game against the Council Bluffs Browns, losing 8-0, with all eight runs scoring in the home fifth inning. Matchett had pitched to the minimum 12 batters through the first four, but then everything fell apart.54 Perhaps it was a one-off. Two days later, he was mentioned as possible starting pitcher for Abilene.

In the next two or three years, Matchett appears to have played baseball in Saskatchewan, perhaps arriving later in 1946. He was reportedly the playing manager of the Saskatoon Legion in the Saskatoon Senior Baseball League.55 In August 1947 a story in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix reported that he had pitched at Cairns Field in Saskatoon for the Canadian Legion ballclub, battling the Colonsay club to a 3-3, 10-inning tie game called due to darkness. “Matchett, colored, pitched, went all the way for Legion and held the visitors to seven hits, four of which Colonsay bunched in the first three frames to score their three counters.” He struck out three.56

In 1948, the start of the season was on May 20, and a newspaper story featured Matchett’s photograph. He was one of three holdovers for the Legion team, described as “Jack Matchett, the popular colored player from Kansas City who broke in with the Legion last year. Matchett, by the way, has taken over the coaching duties. He will do a turn on the mound as well as fill in as an outfielder.”57

A June 22, 1949, report previewed a game “at the senior baseball enclosure” between the Delisle club and the Cubs. The “boss” of the Cubs, Al Verner, wrote the paper, “was also seen eyeing big Jack Matchett. Could it be Matchett is headed for a Cub uniform?”58 Whether he played in 1949 is yet undetermined.

After this, Jack Matchett seems to nearly drop off the map. Perhaps he liked life in California. In 1977, he was listed as one of 14 former Negro Leagues players at an event at the Hollywood Palladium to honor Sammie Haynes. Matchett was identified as with the Kansas City Monarchs; former batterymate Joe Greene and pitcher Chet Brewer were the two other Monarchs.59

There was one nice moment to remember Matchett near the end of his life. As part of Black History Month, he was among more than two dozen former players presented awards at an Old Negro Leagues night held at Sportsman’s Park Auditorium on February 24, 1978.60 Among them was his old batterymate Slow Robinson, who wrote in his book that he had caught two one-hitters thrown by Matchett.61

Jack Matchett died in Los Angeles in March 1979, Seamheads showing a date of March 19.

Without an obituary or other clues, such as relatives who could perhaps be tracked down, the story of Matchett’s later years remains a mystery.

Sources

Thanks to Seamheads.org, Gary Ashwill, Rick Bush, Larry Lester, Andy McCue, Bill Mortell, and Jim Overmyer.

Notes

1 “Open with Memphis Here,” Kansas City Star, May 19, 1940: 19.

2 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 520.

3 Buck Leonard, with James A. Riley, Buck Leonard — The Black Lou Gehrig (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1995), 138.

4 Lubbock Morning Avalanche, May 6, 1938: 2.

5 Frazier “Slow” Robinson with Paul Bauer, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 13.

6 Catching Dreams, 13.

7 Catching Dreams, 17.

8 Catching Dreams, 18.

9 “Big Black Jack’s a Pitcher, Too — Hurls No Hitter, No Runner Against Austin Senators at Midland Park,” Odessa American, July 8, 1938:

10 “Altus Negroes to See Big Black Jack Sunday at Local Ball Park at 3:30,” Odessa American, July 10, 1938: 7.

11 “Oilers Win, 3 to 2, In Brother Duel,” Odessa American, May 25, 1949: 4.

12 “San Angelo Beats Big Jack Matchett,” Odessa American, May 31, 1939: 2.

13 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2016), 111. A photograph of Matchett with Satchel Paige’s All-Stars appears in Slow Robinson’s Catching Dreams on page 23.

14 Catching Dreams, 25.

15 Jada Davis, “Waal, It’s Like This,” Odessa American, March 17, 1940: 7.

16 “Catcher’s Hand Was Too Sore, So ‘Satchel’ Just Couldn’t Pitch Here Last Night, Nohow,” Daily Province (Vancouver, British Columbia), July 12, 1939: 23.

17 “Kansas Monarch Aces Paige and Matchett Tie Whiskers in Knot,” Vancouver Sun, July 17, 1939: 10.

18 Prof. Heaphy’s book indicated that Matchett had been with the Monarchs in 1939, something none of the other standard sources had mentioned. On request, she supplied the articles noted here. See Leslie A. Heaphy, ed., Satchel Paige and Company (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 228.

19 “Monarchs Prepare for 1940 Season in Texas,” Plaindealer (Kansas City, Kansas), April 5, 1940: 3.

20 “Monarchs Win and Lose at Birmingham,” Plaindealer, May 17, 1940: 3.

21 Riley, 520.

22 “Paige to Hurl Here,” Winnipeg Tribune, June 21, 1941: 26.

23 “Monarchs Nip Craters, 5 to 4, on 3-Run Explosion in 9th,” Medford (Oregon) Mail Tribune, July 17, 1941: 4.

24 “Monarchs to Battle Davis in Vaughn Street Game,” Oregonian (Portland), July 22, 1941: 23.

25 “Monarchs Win by 8-4 Score,” Oregonian, July 23, 1941: 29.

26 “Clowns Loom as Strongest in New League,” Detroit Tribune, April 25, 1942: 8. That Matchett spent 1941 with Paige’s touring team is also supported by “‘Pepper’ Bassett Signed by Clowns,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, June 3, 1942: 17.

27 “Clowns Will Open Season on April 1,” Chicago Defender, March 28, 1942: 21.

28 “Monarchs Take Doubleheader from Chicago in The American League Opener Sunday, 7-4; 6-0,” Kansas City Call, May 15, 1942.

29 “Only 2 Monarch Hits,” Kansas City Star, May 18, 1942: 9.

30 “Elites Lose Night Game to Monarchs,” Afro-American (Baltimore), June 20, 1942: 27.

31 Associated Press, “Claims 25 Negro Stars Good Enough for Majors,” Chicago Daily Times, July 30, 1942: 78. If the 1908 birthdate is correct, Matchett was 34 years old at the time.

32 ANP, “Owner of Monarchs Okeys Big League Tryout,” Plaindealer, August 7, 1942: 34.

33 “Shutouts for Monarchs,” Kansas City Times, August 6, 1942: 13.

34 Wendell Smith, “Third Straight Loss Dooms Grays Hopes,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 19, 1942: 17.

35 Catching Dreams, 62, 94, 95.

36 For the “big four” comment, see, for instance, “Monarchs to Show Powerful Outfit,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield), September 12, 1943: 17. A “Big Jack Matchett” reference is found in “Parker, Royal Nines Battle at Lane Field,” San Diego Union, October 31, 1943: 39.

37 Statistics come from Seamheads, at seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1943.

38 Paige and McDaniel combined on a 2-0 shutout in the first game, whitewashing the Chicago American Giants twice. “No Run for the Giants,” Kansas City Times, May 17, 1943: 8.

39 “Monarchs Lose in 12th,” Kansas City Times, May 25, 1943: 14.

40 “Matchett’s Single in 9th Beats Chi Before 18,000,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 5, 1943: 18.

41 “Three Top Ballclubs in Doubleheader at Local Park Today,” Long Beach Independent, October 17, 1943: 24.

42 “Parker’s Nine to Boast Real Power Lineup,” San Diego Union, October 22, 1943: 22. That the article placed Matchett in the wrong league doesn’t inspire confidence in the accuracy of the total.

43 “Monarchs Score in 9th Inning, Beat Giants 4-3,” Chicago Sun, May 31, 1943: 24.

44 “Lindell Hurls Tonight as Majors, Negroes Vie,” Los Angeles Times, November 10, 1943: A10; “Black, Matchett in Mound Duel,” Los Angeles Times, November 14, 1943: 23.

45 Advertisement, San Antonio Light, May 7, 1944: 21.

46 “Kansas City Splits with Memphis Red Sox,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 9, 1944: 12.

47 “Bell’s .515 Tops Hitters,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 3, 1944: 12. Bell was in the Negro National League.

48 Ric Roberts, “Grays and Kansas City Split Before 15,000,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 1, 1944: 12.

49 “North, South Battle Today,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 1, 1944: 24. Paige and McDaniel handled the pitching chores in the game, a 6-1 win.

50 Catching Dreams, 154, 155.

51 “Grays Defeat Kansas City,” Chicago Defender, June 30, 1945: 7. Matchett had previously pitched in the June 2 game against the Barons, a 4-3 win. See “Barons Lose to Kansas City,” Chicago Defender, June 9, 1945: 7. Stories as late as August include him as a member of the Monarchs pitching staff. See, for instance, “Black Barons Clash with Philadelphia; Yanks With Kay See,” New York Amsterdam News, August 11, 1945: B8.

52 “Negro Baseball Season Opens,” Chicago Sun, May 5, 1946: 38. See also “Negro Nines Open Today in Sox Park,” Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1946: A2.

53 See “Black Eagles Vie with Fort Worth, Abilene Reporter-News, June 19, 1946: 7; “Black Eagles Vie with Waco Today,” Abilene Reporter-News, June 30, 1946: 26; and “Black Eagles Lose to Waco ‘9,’ 7-4,” Abilene Reporter-News, June 30, 1946: 8.

54 “All Scoring in Fifth as Browns Win,” Daily Nonpareil (Council Bluffs, Iowa), July 27, 1946: 5.

55 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 110. Their book says he started in Saskatoon in 1946.

56 “Colonsay, Legion in Tie Game,” Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan), August 6, 1947: 11.

57 “Senior Ball Starts Tomorrow,” Star-Phoenix, May 19, 1948: 19.

58 Star-Phoenix, June 22, 1949: 17.

59 “Chico Renfroe, “Los Angeles Honors Former Atlantan,” Atlanta Daily World, October 6, 1977: 14.

60 Brad Pye Jr., “Prying Pye,” Los Angeles Sentinel, March 2, 1978: B1. The venue is now known as Jesse Owens Community Regional Park. The others honored included Chet Brewer, Don Newcombe, Effa Manley and her late husband Abe Manley, Fran Matthews, Frazier Robinson, Herb Souell, and Quincy Trouppe.

61 Catching Dreams, 207, 208.

Full Name

Clarence Jack Matchett

Born

February 4, 1908 at Palestine, TX (USA)

Died

March 19, 1979 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.