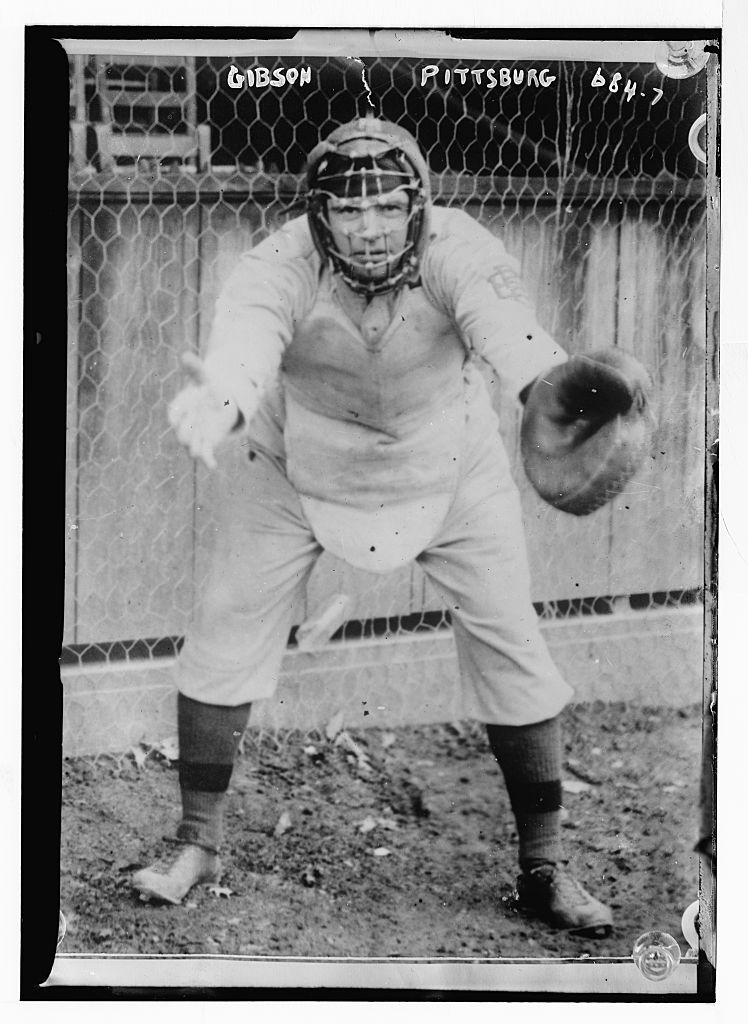

George Gibson

Over the three-year period from 1908 to 1910, Pittsburgh Pirates catcher George Gibson averaged 144 games behind the plate per season, an unheard-of figure for a catcher during the Deadball Era. “Wagner, Clarke, and Leach have been set above all others in allotting credit for Pittsburgh’s success, but there is a deep impression in many people’s minds that ‘Gibby’ was the one best bet,” wrote Alfred H. Spink in The National Game. Though he wasn’t much of a hitter, as evidenced by his lifetime .236 batting average, Gibson was generally regarded as one of the NL’s premier catchers because of his stellar defensive skills and his deadly, accurate throwing arm. When his playing days were over, the popular former backstop turned his reputation as a smart player and square shooter into a moderately successful managing career, compiling a 413-344 record in parts of seven seasons as one of the first Canadians ever to manage in the major leagues.

Over the three-year period from 1908 to 1910, Pittsburgh Pirates catcher George Gibson averaged 144 games behind the plate per season, an unheard-of figure for a catcher during the Deadball Era. “Wagner, Clarke, and Leach have been set above all others in allotting credit for Pittsburgh’s success, but there is a deep impression in many people’s minds that ‘Gibby’ was the one best bet,” wrote Alfred H. Spink in The National Game. Though he wasn’t much of a hitter, as evidenced by his lifetime .236 batting average, Gibson was generally regarded as one of the NL’s premier catchers because of his stellar defensive skills and his deadly, accurate throwing arm. When his playing days were over, the popular former backstop turned his reputation as a smart player and square shooter into a moderately successful managing career, compiling a 413-344 record in parts of seven seasons as one of the first Canadians ever to manage in the major leagues.

The son of a bricklayer and building contractor, George C. Gibson was born on July 22, 1880, in London, Ontario. His first job was carrying buckets of water to the laborers his father employed, and although he eventually learned the bricklaying trade, his first love was baseball. George was known by several nicknames over his lifetime, but the most popular one was “Moon.” Though some sources suggest that the nickname was inspired by his round, moon-shaped face, he actually picked it up because as a youngster he’d played on a sandlot team known as the Mooneys. Gibson began his amateur career as a second baseman, but by the time he was 12 his already strong throwing arm landed him a position as a catcher on the church league’s Knox Baseball Club. From there he gained additional experience with the Canadian League’s West London Stars and the London City League’s Struthers and McClary clubs.

Gibson played his first professional game in 1903 with Kingston, New York, of the Hudson River League, but that August he was purchased by the Eastern League’s Buffalo Bisons, managed by George Stallings. Moon joined the Bisons on September 2, replacing the injured Buffalo first baseman, hitting a single off Baltimore’s Hooks Wiltse, and successfully handling ten putouts. “I didn’t get paid much,” he recalled, “but it sure beat hauling bricks!” At the end of the 1903 season, Stallings released Gibson to the Eastern League’s Montreal Royals amidst rumors that the young catcher had talked back after his foul-mouthed manager had chewed him out for missing a sign. After one full season in which he batted .204 and a half season in which he batted .290, Montreal sold him to the Pittsburgh Pirates in late-June 1905.

The first time Gibson walked into the Pittsburgh dressing room, Honus Wagner took one look at the rookie and hollered, “Here comes Hackenschmidt.” (Wagner was referring to George Hackenschmidt, a famous championship wrestler at the time.) Gibson stood 5’11.5″ and weighed 190 pounds, about the average size of a modern major leaguer. Wagner’s comment illustrates how the size of baseball players has changed over the last century. It also shows the type of impression a modern major leaguer of even average size would make if he could step back in time to enter a clubhouse of the Deadball Era.

Catching veteran twirler Deacon Phillippe in his major-league debut at Cincinnati on July 2, “Hack” Gibson recorded six putouts, two assists, and one error. In The Glory of Their Times he explains how the error occurred on a throw to second base: “The first time one of the Cincinnati players got on first base, he tried to steal second. I rocked back on my heels and threw a bullet, knee high, right over the base. Both the shortstop and second baseman—Honus Wagner and Claude Ritchey—ran to cover second base, but the ball went flying into center field before either of them got near it. I figured they were trying to make me look bad, letting the throw go by, because I was a rookie. But Wagner came in, threw his arms around me, and said, ‘Just keep throwing that way, kid. It was our fault, not yours.’ What had happened was that they had gotten so used to Heinie Peitz‘s rainbows that any throw on a straight line caught them by surprise.” Although he posted back-to-back batting averages of .178 in 1905-06 and allowed 31 passed balls during the latter season, Gibson diligently studied the mental game of baseball under Fred Clarke’s tutelage and worked hard to improve his skills. Years after his retirement he credited Clarke with teaching him to play intelligent baseball and boasted that “thinking was my real specialty.”

Gibson’s greatest season was the phenomenal 1909 campaign, in which the Pirates posted a 110-42 record. That year he caught 150 regular-season games for the Corsairs, including a remarkable string of 134 consecutive games to set an NL record. “There is no doubt but that Gibson could have caught every game of the National League schedule had it been necessary for him to do so,” wrote Spink. “However, the pennant was clinched many days before the wind-up and Clarke gave Gibson the rest he so richly deserved.” He never missed a game despite “black and blue marks imprinted by 19 foul tips upon his body, a damaged hand, a bruise on his hip six inches square where a thrown bat had struck, and three spike cuts,” and he even managed to post one of his better offensive seasons: .265 with 25 doubles, nine triples, two home runs, and 52 RBI. In the midst of his streak, Gibson slugged a double for the final hit in Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park on June 29, and the next day captured the Pirates’ first hit (a single) in the new Forbes Field. On the eve of the World Series, press reports described him as “far and away the best catcher in the National League.” The London Free Press, his hometown newspaper, even credited him with the World Series success of pitcher Babe Adams: “His ability to quickly discover the weakness of the Detroit heavy hitters undoubtedly was the cause of Adams’ strength.”

During his Pittsburgh prime, Gibson led all NL catchers in fielding percentage three times (1909, 1910, and 1912), and after injury-plagued seasons in 1912-13 he managed to hit a career-best .285 in 1914. In August 1916 the 36-year-old Gibson was placed on waivers and claimed by the New York Giants, but he refused to report that year. John McGraw persuaded him to join the Giants as a player-coach in 1917, and the following May he accepted a coaching position with Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League. The 1918 season closed early because of the war, however, and Gibson returned to his Ontario farm until he was hired in 1919 to coach the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League.

Gibson spent one season in Toronto before he was summoned to manage the Pirates from 1920 to 1922. George again retired to his farm after spending 1923 as a coach for the Washington Senators, but he returned to baseball in 1925 to coach the Chicago Cubs, finishing the season as manager after Rabbit Maranville was dismissed. Though he wasn’t reappointed for 1926, he became a scout for the Cubs until he took over the Pirates again in 1932. During his two stints as Pittsburgh manager, Moon developed a reputation as a taskmaster and strict disciplinarian. “The Pirates have more signals than the Notre Dame football team,” wrote one reporter, “and Gibson insists that every order be carried out to the letter.” Though he recorded a lifetime .546 winning percentage as a manager, he was intolerant of mental mistakes and his temperament left him ill-suited to the task of managing locker-room politics. In June 1934 the Pirates replaced Gibson with Pie Traynor.

George Gibson remained active in baseball, sponsoring amateur clubs and serving as the vice-president of the Pirates’ London farm club in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League in 1940-41. At the end of his baseball career he quietly retired to his Ontario farm with his wife, Margaret (McMurphy), whom he had married in 1900, and their three children, George Jr., William, and Marguerite. George enjoyed gardening and hunting and learned to become an expert curler. He died of cancer at the age of 86 on January 25, 1967, in Victoria Hospital. Gibson was inducted into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame in 1958 and the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

Cornies, Larry. “The Mooney of Fame.” London Magazine. March/April 1987.

DeValeria, Dennis and Jeanne Burke. Honus Wagner. Henry Holt, 1995.

Lieb, Fred. The Pittsburgh Pirates. Putnam, 1948.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Clipping File.

Shatzkin, Mike. The Ballplayers. William Morrow, 1990.

Full Name

George C. Gibson

Born

July 22, 1880 at London, ON (CAN)

Died

January 25, 1967 at London, ON (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.