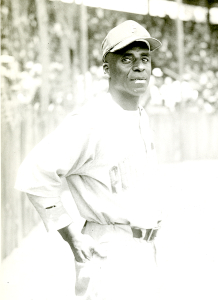

Homer “Goose” Curry

He was a baseball man in the purest and most complimentary sense of the term, at various times in his professional career playing as a pitcher and an outfielder, along with a few occasions at second base, and finally working as a manager over a 26-year professional span. “He was a good contact hitter, had good speed, and was an adequate fielder … had a shrewd baseball mind,” wrote James Riley in his magnum opus, the Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues,1 but that description is too bland to measure Goose Curry’s long baseball life.

He was a baseball man in the purest and most complimentary sense of the term, at various times in his professional career playing as a pitcher and an outfielder, along with a few occasions at second base, and finally working as a manager over a 26-year professional span. “He was a good contact hitter, had good speed, and was an adequate fielder … had a shrewd baseball mind,” wrote James Riley in his magnum opus, the Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues,1 but that description is too bland to measure Goose Curry’s long baseball life.

Homer Curry was born in Mexia, Texas, about 30 miles east of Waco, on May 19, 1905. He was the third child of five and the third son of parents Ben and Myrtie (Rhodes) Curry. His father farmed a family plot of land in the area.2 By that time, as well, Texas was developing what became a rich baseball tradition. Waco had produced Andrew “Rube” Foster, the father of the first Negro National League in 1920. Other notable alumni from the region included Louis Santop, pitcher Cyclone Joe Williams, and Crush Holloway. That impressive roster was augmented by a legion of leagues and city teams that equaled their White contemporaries in both talent and local enthusiasm.

Although there is not much documentation of Curry’s early life, given his professional success, it is almost certain that he not only played the game in central Texas, but played it well. While he completed only the fifth grade in school, he was clearly a gifted athlete.3 His baseball anonymity expired in 1928, when at age 23 he joined the Cleveland Tigers and hit .352 as a pitcher and occasional outfielder. The Tigers were Cleveland’s entry in the Negro National League that year, but their ownership was somewhat unstable and the team finished last with a 20-59 record.4 It was likely the paucity of talent on the squad that created an opportunity for the young Texan to crack into the big leagues.

At 6-feet-2 and 180 pounds, Curry was a natural power hitter, and his OPS+ of 131 clearly established his baseball bona fides, despite his relatively young age of 23. He batted left-handed and pitched right-handed. On the mound, Curry threw 125⅔ innings that rookie year but allowed an ERA of 4.66, and his ERA+ left him just below league average.

From Cleveland, Curry moved on to work for the Memphis Red Sox beginning in 1929. He remained with the team through 1930, pitching and playing the field, then returned for the 1932 and 1937 seasons, and again in 1949-1950 and 1953-1955 in the surviving Negro American League. In Memphis in 1930, he was named one of the two regular starting pitchers, but the results were not optimal. There is some question as to his actual won-lost record that season, with various sources listing it at either 4-3 or 5-3, but his ability in the field, as a two-way player, largely ensured him of a spot on the roster.

There is not a great deal of information available about Curry’s wife. Marie (Miles) Curry was born in west Tennessee in approximately 1906, and Curry likely met her during his time in Memphis. While they never had children, they had a lifelong marriage. The relationship fostered a bond between player and city that also lasted until Curry’s death.

Curry was, as some biographers have described utility players in the early days of the organized Negro leagues, a bit of a figurative baseball tumbleweed, moving from town to town and team to team in search of a roster spot and a paycheck. In 1932 he spent time with Memphis as player and manager, and by then was locally acknowledged as a terrific outfielder. For 1933 he moved to the Nashville Elite Giants. He played well there and earned a number of favorable mentions in the press. One 1933 article referred to him as “fleet footed … the class of the league when it comes to the outfield.”5 In 1936 the team moved to the mid-Atlantic region of the country, between Washington D.C. and Baltimore, and Curry made the move as well. That season he played well enough to lead all outfielders in voting for the 1936 East-West All Star Game in Chicago. Still, despite garnering more votes than luminous contemporaries like Cool Papa Bell and Jimmie Crutchfield, Curry did not appear in the game.6

But there were other, unfortunately memorable moments as well. As historian Brent Kelley wrote about one particular one in his 1995 book Voices From the Negro Leagues, relating an anecdote from Henry Kimbro: “[Luis Tiant, he of an incredibly deceptive screwball] was pitching for the Cuban Stars, Fred McCreary was umpiring, Goose Curry was the hitter. Tiant went up and down and grunted and throwed the ball and Goose Curry swung and said ‘Jesus Christ! Man, how’d I miss it?!’ Fred McCreary said, ‘I oughtta call you out. That man throwed to first base.’”7 There is no record of the play in the newspapers, but Kimbro swore it to be true.

Curry took the helm as player-manager for Memphis for part of the 1937 season, yet even with the new responsibilities, he excelled at the plate. That year his OPS of .952 equated to an OPS+ of 160, his career high. He spent 1938 with the New York Black Yankees. At age 33, he was credited with seven league appearances as an outfielder with New York, pitching in three as well, but his OPS+ declined to 111. The following year, 1939, he was primarily an outfielder, and he split time between New York and the Baltimore Elite Giants, batting .343 and posting a terrific OPS+ of 151 for the full season.8 Curry’s bona fides as a hitter were unquestioned. His fielding prowess, though, was even more exciting.

In one particularly memorable game in 1939, Josh Gibson launched what appeared to be at least a triple, perhaps even home run number 60 for the year, in Pittsburgh:

“It was a beautiful fly,” the Pittsburgh Courier reported, “and the fast-stepping Josh had rounded second and was heading toward third before the ball hit the fence. It looked like a sure homer. But suddenly someone flashed into the picture back there between the fence and the ball. It was the New York Black Yankees’ fleet outfielder, Homer ‘Goose’ Curry. He galloped back there like a wild colt on a rampage. … His speed made him collide with the fence. He hit the wall and bounced away like a rubber ball. Then he straightened up and leaped in the air. The ball dropped near the fence and landed in Curry’s glove. It bounced out of his mitt. It was a dramatic moment. Then he made a second dive for the bounding sphere in an attempt to retrieve it. His snatch was sure. He grabbed it and held tight. It was a great catch. We’ve seen many a big league game out at the Pirates park, but never a more thrilling catch than ‘Goose’ Curry’s. … It terminated a Homestead rally and the Grays’ goose was ‘cooked.’”9

That year, 1939, as well, Curry was selected as a coach for the East team in the East-West All Star Game.10 Overall the year was a grand success for the outfielder. He did not pitch at all that season for Baltimore, at least in league play, but his two appearances in the outfield earned him a permanent spot in the championship lore of the city.

The 1940 season was split between the Black Yankees and the Elite Giants after Curry was sold to Baltimore in midseason.11 Curry remained with the Elites through 1941. Between those two seasons, Curry did make a trip to the West Coast for winter ball. His 1940 draft registration card confirms that he was residing in Los Angeles at that time, working for Tom Wilson and the Elite Giants, but also married to wife Marie, who was still in Memphis.12 Curry was spending the winter of 1940-41 playing in the California Winter League on the Baltimore squad alongside Henry Kimbro, Biz Mackey, and Felton Snow, among others. Although other winter leagues, such as the one in Puerto Rico, had robbed the California variant of some of its baseball luster, it was still a terrifically competitive environment. In nine league games, Curry was credited with three doubles and a home run in 29 at-bats and posted a .379 average for the interim season.13

Back on the diamond in 1941, Curry played mostly in the outfield, and logged a .304 average and an OPS+ of 133. Even at his advancing age (36), he reached what became career highs in plate appearances (255) and at-bats (214), and swiped seven bases as well. In February 1942 Curry changed professional lanes and accepted the job as manager of the Philadelphia Stars.14 According to the Baltimore Afro-American, “Curry is popular throughout the league and best known for his scrappy, enthusiastic leadership.” According to news reports, the only reason that Baltimore owner Tom Wilson agreed to the transaction was that Stars owner Ed Bolden promised to name Curry the manager as well as outfielder.15

Curry was the player-manager of the Stars from 1942 to 1947. In 1942, at age 37, he batted .285. Curry was seen as a successful manager, even if the records do not support that claim with much vigor. He was also unafraid of conflict. As Riley wrote:

As the Stars’ playing manager in 1946, he was involved in a brouhaha during the Newark Eagles’ ace Leon Day’s opening day no-hitter against his club. The incident began when the umpire called the Eagles’ Larry Doby safe on a close play at the plate. Stars’ catcher Bill Cash was infuriated and knocked the arbiter to the ground. Curry, who was already moving in from his position in right field to voice his objection to the call, arrived in time to kick the felled umpire while he was still on the ground. A riot ensued, with fans spilling out of the stands, necessitating the use of mounted police to clear the field.16

Overall, Curry is credited with a 203-207-11 record over his six seasons managing the Stars, and the fact that Ed Bolden continued to rehire Curry each year is testament to the confidence Curry earned from players and peers. But managers are hired to be fired, says the conventional wisdom of generations of writers, and in December 1947, Bolden fired Curry. That none other than the legendary Oscar Charleston took his place did not particularly ease the blow.17

Curry’s formal time in the recognized Negro leagues (including the first and second National Leagues, the American League, and the Southern) ended after that 1947 season. He was a lifetime .301 hitter with a career OPS of .825 and an OPS+ of 124. In contrast with James Riley’s introduction of the player earlier, Goose Curry was much more than a “good contact hitter” with “good speed.” He was a lethal hitter for the greater part of 20 years, and in his age-42 season, as player-manager of the Stars, he logged 8 hits in 17 at-bats. He could pitch, but not at the same level as he slugged. His career ERA+ of 81 was 19 percent below the league averages of his time, and his lifetime won-lost record of 26-39 was similarly pedestrian.

When the second Negro National League folded after the 1948 season, Curry headed back south, managing and playing for the Atlanta Black Crackers.18 Proving that he was not yet too old to swing a bat, not quite ready for the rocking chair, Curry impressed the locals in a May 1949 game against Chattanooga with a dramatic ninth-inning grand slam that produced a 7-6 Atlanta win.19 As if that were not sufficient, Curry also homered in the nightcap as his contribution to the 3-1 win and the doubleheader sweep.

Curry spent the succeeding years managing several teams throughout the South, including the Memphis Red Sox, the Louisville Black Colonels, the Birmingham Black Barons, and again the Memphis Red Sox (now of the four-team Negro American League).20 In 1956, his final season in the Negro Leagues, he managed the West team in the East-West Game.21 After his playing days ended, Curry did some scouting and coaching for the Memphis Red Soxand never strayed too far from the game.22

On March 30, 1974, Homer Curry died following a long illness, two months before his 69th birthday.23 He is buried at the Mount Carmel Cemetery in Memphis.24

Sources

All baseball statistics are derived from various web pages on the Seamheads.com site.

Photo credit: Homer “Goose” Curry, Temple University, John W. Mosley Collection.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 220.

2 1920 United States Federal Census: Texas/Limestone (County)/Justice Precinct 4/District 0090, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4392085_00204?pId=112958570

3 1940 U.S. Census/Memphis City/Ward 51/Block 19 (April 1940). https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/38243281:2442?tid=&pid=&queryId=c386cf307dd641b156ba2927238dbbe2&_phsrc=heb12&_phstart=successSource.

4 “Cleveland Tigers (Baseball), in the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History curated by Case Western Reserve University. Online: https://case.edu/ech/articles/c/cleveland-tigers-baseball.

5 “Memphis Tops Southern Ball League,” Chicago Defender (National edition), May 20, 1933: 8.

6 Larry Lester. Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 93.

7 Brent P. Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1998), 59.

8 “Black Yanks Leave for Carolinas: New Faces on Harlem Ball Club,” Chicago Defender, April 15, 1939.

9 Chester L. Washington, “‘Sez Ches’: Josh Caught in the Act,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 20, 1939: 16.

10 “The East Pits Its Best Against West Again Sunday: Teams Are Bolstered for Game; East’s Second Sacker from Beale Avenue,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1939: 9.

11 J. Blow, “Western League Gets Satchel Paige: Baltim’re Gets Bud Barbee, ‘Goose’ Curry; Manleys Lose Paige after June Meeting of Two Negro Leagues,” New York Amsterdam News, June 29, 1940.

12 Homer Curry, United States form D.S.S. Form 1, dtd. October 16, 1940.

13 “California Winter League (1940-1941),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research (CNLBR), online: http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Stats/CWL/1940s/California%20Winter%20League%20(1940-41).pdf.

14 “Curry New Manager of Philly Stars,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 21, 1942: 23.

15 “Philly Stars Manager,” Chicago Defender, July 25, 1942: 20.

16 Riley, 220.

17 Dusty Ballard, “Oscar Charleston Signed to Manage Stars for 1948 Season: Goose Curry Receives Unconditional Release,” Philadelphia Tribune, December 23, 1947: 11.

18 “Black Crax Work Overtime for Opener Against Black Yankees,” Atlanta Daily World, March 21, 1948: 7.

19 “Black Crackers Beat Choo Choos on Curry’s 9th Inning Homerun,” Atlanta Daily World, May 26, 1948: 5.

20 Russ J. Cowans. “The Goose Made a Mistake,” Chicago Defender, September 1, 1956: 18.

21 “Curry, Steele NAL Managers,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 28, 1956: 15.

22 “Birmingham Giants in Tryouts,” Chicago Daily Defender, March 15, 1956: 21.

23 “Goose Curry Dies,” Northwest Arkansas Times (Fayetteville), April 4, 1974: 2.

24 “Homer Curry,” Find-a-grave online: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/255315864/homer-curry#source.

Full Name

Homer Curry

Born

May 19, 1905 at Mexia, TX (USA)

Died

March 30, 1974 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.