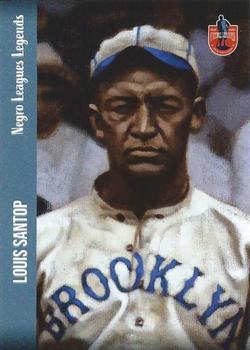

Louis Santop

“Santop hit the ball farther than anybody.”1 — Jesse Hubbard

If there is one player who stands out from the early days of the Negro League era—1900 to 1925—it is Louis Santop. He was talented, with the then-rare ability to hit the long ball in what was known as the dead-ball era. He was personable and fun to be with despite his stern demeanor. And he was accomplished, anchoring many a team lineup and playing in some of the most memorable early Negro League games.

If there is one player who stands out from the early days of the Negro League era—1900 to 1925—it is Louis Santop. He was talented, with the then-rare ability to hit the long ball in what was known as the dead-ball era. He was personable and fun to be with despite his stern demeanor. And he was accomplished, anchoring many a team lineup and playing in some of the most memorable early Negro League games.

Louis Santop Loftin, one of eight Negro League Hall of Famers from Texas, was born on January 17, 18892 to Andrew Loftin and Belle Ross, both born as slaves, in Fort Worth, Texas.3 Louis was the oldest of five children.4 Andrew Loftin was a farmer and so was Louis, according to 1910 Census data, which was also around the time young Louis began his baseball career.5

Santop first played for the Fort Worth Wonders in 1909, a North Texas semi-pro team that had formed a few years earlier. Santop then competed briefly in 1910 with the Oklahoma Monarchs based in Guthrie, OK. The Monarchs were an independent club loosely affiliated with a league of Western Independent Clubs, in which the Monarchs finished next to last that year.6 (Seamheads shows Santop on the Monarchs roster, appearing in at least one game.)

The year 1911 would find Santop far from Texas–in Philadelphia to be exact–playing for the Philadelphia Giants. How Santop got there is answered by W. Rollo Wilson, columnist of the Pittsburgh Courier. According to Wilson, “Grant ‘Home Run’ Johnson, then manager of the Philadelphia Giants, heard of him [Santop] as being a wonderful batsman and brought him to this city in 1911.”7

A mainstay in early eastern Black baseball, the Philadelphia Giants were a part of Nat Strong’s National Association of Colored Professional Clubs. But by 1911, when Santop joined Philadelphia, Strong’s hold on eastern baseball was weakening. That year, New York promoters Jess and Ed McMahon formed a new club, the New York Lincoln Giants, and hired Sol White to manage the team.8 The Lincoln Giants became a counterweight to the Brooklyn Royal Giants, the latter being owned by J.W. Connor with Nat Strong as its promoter and booking agent. White quickly began raiding other teams to fill out the roster. No friend of Rube Foster, White signed Home Run Johnson, Pop Lloyd, and James Booker from Foster’s Chicago team. He also raided the Philadelphia Giants and brought in Santop, Dan McClellan, Cannonball Redding, and Spottswood Poles.9

The demise of the Philadelphia Giants due to player raids was not long in coming. In the August 3, 1911 issue of the New York Age, Lester A. Walton wrote:

There has been much stirring in the baseball world this week. The Philadelphia Giants disbanded Tuesday as many have been predicting for some weeks. When Redding and Santop, the crack battery quit the team a few weeks ago for the Lincoln Giants, the team was materially weakened. Then business has not been the best for the nine, and the owner decided Tuesday to disband for the season.10

Santop moved to New York in mid-summer to become part of an exceptionally talented Giants team consisting of Joe Williams, Cannonball Redding, Pop Lloyd, Jimmy Lyons, Spotswood Poles, and Santop. The pitcher/catcher duos of Redding/Santop and Williams/Santop were quickly heralded as “kid batteries” and the game’s new generation of stars.

In 1912, a Cuban team called Club Fe hired Spots Poles, Judy Gans, and Santop from the Lincoln Giants (which had traveled to the Cuba for a series against local teams) to improve their chances to win a pennant. 11 This was Santop’s first winter in the Caribbean.

Stateside, the Lincoln Giants were Santop’s first real home; he would play for the team through 1914 at a time when he began to make a name for himself. In those years, the Lincoln squad had as its primary competition the Brooklyn Royal Giants and the Cuban Giants. Seamheads research in this period offers a good look at Santop’s hitting skills. His batting average in the four-year period was a composite .319. In 1911 he batted .317 with Philadelphia and then .311 with Lincoln and then .280 in 1912, .356 in 1913 and .375 in 1914, all with Lincoln.

Santop was a power hitting lefty, about 6’2” and over 200 pounds. The home run totals captured by Seamheads are sparse, reflective of the deadball era (1900-1919), but stories not just of Santop’s hitting, but his power, were the norm. Historian William McNeil writes,

The left-handed slugger quickly earned a reputation for his hitting prowess in the Negro League cities around the country, and he became the Giants’ main attraction. As a result, he had to play in just about every one of the Giants 200 games a year to satisfy the crowd. Naturally, he was also paid a star’s salary.12

A home run exploit often told was his 485-foot home run in Elizabeth(port), New Jersey in 1913 when he was with the Giants. A local newspaper account wrote, “Doc Scanlan, until recently a major league pitcher, pitched for the TABS team and Santop lit one of his curves for the longest home runs ever made at the park.” The Giants box score in that game was one for the ages: Spottswood Pols, Judy Gans, John Henry Lloyd, Home Run Johnson, Santop, Doc Wiley, Leroy Grant, Bill Francis, Cannonball Redding, and Smokey Joe Williams.13

With that lineup it was no wonder the Lincoln Giants were the top team in the East in 1913, purportedly winning 101 of 107 games played.14 Their preeminence called for a squaring off against the other dominant Negro team of the day—the Chicago American Giants owned and managed by Rube Foster. In a series that began on July 27, the teams played twelve games. Lincoln won seven of them. Although Santop did not have a particularly memorable series, it was a preview of what became his penchant for being in the right place at the right time in games of consequence, either against Negro League rivals or Major Leaguers.15

A good example of the latter came later that year in an October 5 exhibition that the New York Age highlighted between the Lincoln Giants and Philadelphia Nationals. Led by Smokey Joe Williams who would outduel Grover Cleveland Alexander, and with Poles, Gans, Lloyd, and Santop in the lineup, Lincoln would defeat their National League opponent 9-2.16

In 1914, the McMahons ceded control of the Lincoln Giants name, selling the team to James J. Keenan. They then formed a rival team, the Lincoln Stars, signing several of the Giants’ players including Santop. The 1915 Lincoln Stars were loaded. They had Cannonball Dick Redding and Franklin Doc Sykes as pitchers, Bill Pierce as catcher, Zack Pettus at first base, Bill Kindle at second, Sam Mongin at third, John Henry Lloyd at short, Judy Gans in left, Spottswood Poles in Center, and Santop in right and as backup catcher to Pierce.17 The Stars did not disappoint and appeared in an All-Colored Championship against the Chicago American Giants. The 11-game series culminated in a 5-5 tie, ending with the last game called because of darkness in the fourth inning with the Stars ahead by one run.18

After the end of the series, Rube Foster enticed John Henry Lloyd, Judy Gans, and later Santop along with Oscar Charleston, Bingo DeMoss, Bruce Petway, Cannonball Redding, Smokey Joe Williams, and Cristobal Torriente to join the American Giants. Seamheads shows a handful of Chicago games in which Santop played at the end of the season but he, like many of the others, departed Chicago at the culmination of the 1915 campaign. Santop would return to the Stars in 1916.

Santop, now 26, was coming into his prime. He hit for contact and power and while not quite so revered for his catching skills, had a strong arm and was a very proficient battery mate to some of the best pitchers of the day. When it came to his personality, according to McNeil,

In spite of his size, Louis Santop was an easygoing, friendly individual who didn’t use his size to intimidate other players. On the other hand, he did grow up in a tough area and often had to fight to survive. He carried that toughness into the Negro Leagues with him, so it was best not to provoke him. He had enormous strength, and he could handle himself if he had to.19

The next several years found Santop moving around. This had much to do with the unsettled nature of team ownership and the financial instability of Negro baseball in general. Santop’s sojourn with the Hilldale Daisies, where he would end his career, was on the horizon. But it was in the last several years of the 1910s that he would emerge as the star player of the Negro game. Santop began the 1916 season with the Stars, his 1915 squad. Seamheads shows Santop playing in 26 games for Lincoln, making 120 plate appearances, and batting a robust .351. His OPS was .987. Those numbers would help lead the Stars to another of the “championship of the World” series that summer between the Stars and the Chicago American Giants, this time with Chicago winning four games to three.20

Well into the 1916 season, Nat Strong, the Brooklyn Royal Giants’ co-owner and business manager, enticed Santop to jump to the Royals. According to the Times Union,

Santop, that star hitter and catcher of the Lincoln Stars…left for Sharon, Connecticut to join the Brooklyn Royal Giants. Santop is the best batter in the colored ranks and will alternate the catching department with Specs Webster and play in the outfield in place of Harry Desport, who had his arm broken recently.21

Seamheads unearthed ten games and 43 plate appearances for Santop with Brooklyn, and a batting average of .436. His composite stats for the year were a .375 batting average and an OPS of 1.035.

The year 1917 would find Santop comfortably ensconced with Brooklyn. His slash line spoke for itself: .393/.460/.539 with an OPS of .999. Among the consortium of eastern clubs that year, the Royal Giants were middle of the pack.

Later that season, Santop would be on the move and make his first appearance for Hilldale in its famous series against a squad with several major-league players. Sometimes known as the Daisies and based in Darby, Pennsylvania just west of Philadelphia, Hilldale was established as a boys’ team in 1910, and then incorporated as a professional club in 1916. Ed Bolden, its owner, quickly established it as a team worth playing for. Players would be attracted to Hilldale thanks to its “large crowds, stable finances, and African American management”.22

Bolden’s Hilldale team did so well in 1917 that he was able to schedule a three-game series in October with the “All Americans,” a team that included some Philadelphia A’s players and a few other American Leaguers. To compete with the Major League squad in the autumn, Bolden supplemented Hilldale with Santop from the Brooklyn Royal Giants, Dick Lundy from Bacharach, and Smokey Joe Williams, Jess Kimbro, Jules Thomas, and Pearl Webster from the Lincoln Giants. On October 6, 1917 Hilldale defeated the All Americans, 6-2 with Smokey Joe Williams pitching. Although Hilldale would lose two of three to the All Americans, this first cup of coffee with Hilldale would cement a connection that solidified for Santop over the next couple of years and then became his baseball home for the remainder of his career.

Santop was signed by Nat Strong to start the 1918 regular season again with Brooklyn. However, he also found time to play with Hilldale for its celebrated match-up against a team that included several Red Sox and other Major League players after Boston’s World Series champions. Hilldale would lose 4-3 in a pitching matchup of Bullet Joe Bush against Smokey Joe Williams, but Santop would garner four hits in the loss.23

A look at Santop’s records shows a draft registration card (with Nat Strong listed as his employer) from 1918 confirming his induction into the military as part of the World War 1 call up.24 Santop was a Fireman, 2nd Class in the US Navy. earning an honorable discharge on August 13, 1919.25

Santop often supplemented his stateside and Caribbean playing schedules with his participation in the less formal “Coconut” (or “Florida Hotel”) League. It was a spring training of sorts for him and other Negro League elites who participated with him. Author McNeil writes of this time period, “The exclusive Poinciana and Breakers hotels in Palm Beach, Florida, hired the best black baseball players in the country to represent them in the Florida Hotel League during the winters months…The rosters of the two hotels were a veritable who’s who in black baseball,” including Rube Foster, Pop Lloyd, Smokey Joe Williams, Spots Poles, Cannonball Dick Redding and yes, Louis Santop.26 Santop would be a regular—a major draw for the winter games—and play in Palm Beach a handful of winters from 1914 into the early 1920s.

After Santop’s stint in the military in 1918-1919, the New York Herald on May 19 proudly announced his return: “When the Royal Giants face the Bushwicks in their return doubleheader at Dexter Park next Sunday, two new men will appear in the Royals roster, Santop, leading semi-pro backstop, will be mustered out of the navy in time to play in Sunday’s game…”27

A survey of newspaper articles over the course of the 1919 season offers a panoply of monikers and descriptions of Santop that placed him alongside John Henry Lloyd, if not beyond him, as the preeminent hitter of the times: “The great colored catcher,” “the Ty Cobb of colored baseball,” “heavy slugger,” “hard hitting,” “the big catcher,” “formidable,” “home run Santop,” “catcher of gigantic proportions,” “the great,” “the mighty,” “forte to clout homeruns,” “chief propensity to pound out circuit drives,” “Santop and his big stick,” “the power of his whip”; the sobriquets were endless. A typical game summary usually included mention of Santop in the story if not the headline itself (“Two Homers by Santop…Help the Royal Giants Defeat the Silk Sox”).28

The Standard Union reported on its hometown team throughout the year, and if there was one constant it was Santop’s power. “Santop made one of the longest hits ever seen at the local [Recreation] Park, when he hit the ball far over the crowd in deep centerfield [against the Cuban Stars] and walked around the bases.”29 The 1919 season would also be the only one that Santop would manage—about a dozen games for the Royal Giants when Lloyd was with rival Bacharach.

In 1920, Santop landed in Hilldale where he would stay for the rest of his career. He had turned 31, but still had gas in the tank. Hilldale owner Ed Bolden would later say, Santop was “the greatest star and best drawing card we ever had.”30 In fact, Bolden paid Santop a premium for his talents. Holway wrote, “Bolden backed ups his words [regarding Santop’s prowess] by paying his big catcher a princely salary–$450 a month. Santop earned it by playing almost every game the Hilldales played, which meant about 180 or more a season.”31

Because Hilldale was not under the umbrella of the Negro National League formed in 1920, Hilldale was subject to player raids and faced a cabal of Black teams on the East Coast under Rube Foster’s sway that were unwilling to schedule games with Bolden’s team. As a result, Bolden worked hard to establish and maintain local connections through its membership in the Philadelphia Baseball Association (PBA), an organization of which Hilldale was its only black member. The PBA offered a stable source of competition against which to maintain a schedule. Throughout 1920, Hilldale would play mostly local white amateur or semi-pro teams, and in the process, won over 100 games.32

Famously that year, Bolden allegedly used his connections with white entrepreneurs to “book a six-game series against three white major-league all-star barnstorming teams. One of these teams has a puckish Phillie outfielder, at least for that one season, named Casey Stengel. The other had none other than Babe Ruth, coming off an unheard of 54 home runs in his first season with the Yankees.”33 The Philadelphia papers were aglow in their coverage of this competition.

The Ruth games especially turned on the locals, black and white, who couldn’t’ wait to see the white star go head-to-head with black slugger Louis Santop. …while the Hilldales only won one of the six games, Santop impressed the white major leaguers. In the opener of the set against Ruth, he hit two singles and a double, though the Babe would ultimately win the personal battle when in the next game he jerked one clear out of the park [the games were played at Phillies Park] onto Broad Street.34

In 1921, to protect the team from player raids by the newly formed Negro National League (NNL), Hilldale signed on as an associate member of the League but played relatively few games against the NNL. Santop’s Seamheads-derived statistics show solid numbers for 1921 and 1922 with slash lines of .377/.437/.648 (and an OPS of 1.085) in 1921 and .396/.487/.614 (and an OPS of 1.101) in 1922.

Hilldale ended its associate status with the NNL at the end of 1922, frustrated that the arrangements constrained its player signings and scheduling. Instead, in late 1922, Bolden and Nat Strong formed the Eastern Colored League (ECL) as a counterweight to the NNL, setting the stage for the first Colored World Series in 1924.

Bolden used the 1922 offseason to make several key acquisitions whose presence would assure Hilldale’s East Coast dominance for several years. Bolden brought in Nip Winters to strengthen a pitching staff anchored by Phil Cockrell. Also added were John Henry Lloyd, Biz Mackey, George Carr, Jake Stephens, Frank Warfield, and Clint Thomas. These players joined Santop, Otto Briggs, and Judy Johnson to make a formidable 1923 side.35 Although the Lloyd signing as player and manager created tensions, Hilldale did well financially, won over 100 games, and came in first in the inaugural season of the ECL.

In that first year the ECL consisted of Hilldale, Cuban Stars, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, New York Lincoln Giants and Baltimore Black Sox. Hilldale won the league its first three years, earning trips to the newly constituted Colored World Series in 1924 and 1925.

The inaugural World Series in 1924 brought the Kansas City Monarchs and Hilldale together. In League play, J.L. Wilkinson’s Monarchs had bested Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants, and Ed Bolden’s Hilldale squad surpassed the Baltimore Black Sox.

Santop was now a grizzled veteran, yet still an icon in the game. Although Hilldale now had Biz Mackey, who would become one of the all-time defensive catchers in the game, Santop still handled most of the backstop duties with Mackey playing shortstop. Santop’s 1924 slash line for the year was still respectable (and improved from 1923)—.351/.391/.495 with an OPS of .886. Hilldale would win the ECL with a 47-26 record.

The ten-game series, played in four cities from October 3 to 20, ended in victory by the Monarchs, five games to four with one tie. How did Santop fare? He appeared in all but Game Two of the ten games and in 24 at bats had eight hits, with two RBIs, three walks, and two runs scored. Only Judy Johnson hit for a higher average (.364) than Santop for Hilldale. Santop started seven of the nine games he played in.

After the first five games, Hilldale was up three to one (with one tie). Kansas City won Games Six and Seven, leading to historic game Eight in Chicago on October 18. In a matchup between Bullet Joe Rogan and Rube Currie, Hilldale pulled ahead 2-0 on RBIs by Santop in the 6th and George Carr in the 7th. Fast forward to the ninth inning. It would be an inning where Santop became the scapegoat for KC’s comeback win, although other managerial and player miscues also contributed to the Hilldale demise.

With the bases loaded and two outs, according to the Pittsburgh Courier “Duncan then hit an easy foul ball back of home plate which Santop muffed and fell sprawling to the ground. Duncan then came through with a hit, scoring the tying and winning runs.”36

After the tragic ending to Game Eight, Santop nonetheless started Games Nine and Ten. Hilldale came back to tie the Series at 4 games apiece but were shut out 5-0 in Game Ten.

Hilldale’s loss to the Kansas City Monarchs would find Ed Bolden doubling down on his team to ensure its return to the World Series in 1925. For Louis Santop, it would be his last full year in the game.

It almost did not happen. Hilldale released him in February in a salary dump. However, Santop was re-signed a month later.37 Santop would appear in 23 games and have 34 at bats for a Hilldale squad on which Biz Mackey, in his prime at the age of 28, would now bear the catching load. Santop batted a lackluster .176 with an OPS of .449, the lowest of his career.

He would return with Hilldale in a rematch with the Monarchs in the 1925 World Series, which Hilldale would win five games to one. Santop appeared in Games Two and Three, going hitless in two at bats.

Santop began 1926 with Hilldale, but on July 10 the Pittsburgh Courier reported Santop’s unconditional release.38 During the year, newspapers showed Santop playing elsewhere, with the Ambler Black Sox, Santop’s All Stars, Santop’s Broncos (an independent team that he formed in 1928 lasting into the early 1930s)39, a team he helped form called the Philadelphia Cubans, and then again, occasionally, even Hilldale.

Louis Santop also found time to create a home and, at the age of 38 in 1927 he married Minnie B. Robinson. They would have no children. Monte Irvin later reflected, “After he retired as a player, Santop went into broadcasting and ended his days tending bar in Philadelphia.”40 Santop’s radio sojourn was on WELK, a local station that carried African-American programming.41 He was also a Mason, Republican Committeeman, and a clerk in the recorder of deeds office at Philadelphia City Hall.42

An all too brief 15 years later in 1942, Louis Santop passed away. When he died the accolades were both instantaneous and heartfelt. Red Smith, New York Sportswriter, shared that “When he passed away, I got on a train, and I went to Philadelphia for his funeral, because I had seen him play and knew what he could do.”43 Fay Young of the Chicago Defender wrote:

Confined since November 7th, in the Navy hospital in Philadelphia, Louis Santop Loftin better known [simply as] Santop, catcher for the Lincoln Giants…Philadelphia Giants [and Hilldale], died in an oxygen tent from an ailment similar to that which was fatal to Lou Gehrig.44

In 2006, 64 years after his death, Louis Santop was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. By inducting Santop, the Hall affirmed that he was among the greatest Negro Leaguers in the first 25 years of the 20th century.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Steve Rice and Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, Seamheads.com was used as the database of record for all player statistics and team records. Data were accessed as of February 2021.

Notes

1 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 89.

2 Some brief bios of Santop list his birth year as 1890. Santop’s Social Security Application, Official naval records, and his US Passport records confirm the birth date.

3 Texas Marriage Records, 1870, 1880 US Census.

4 1910 US Census.

5 1910 Census.

6Leslie A. Heaphy, The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2003), 27.

7 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” The Pittsburgh Courier, April 10, 1926: 13.

8 Larry Lester, Black Baseball in New York City: An Illustrated History, 1885-1959 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2017), 49.

9 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues: 1884-1955 (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995), 81.

10 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” The New York Age, August 3, 1911: 6.

11 Peter C. Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball: 1864-2006 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2007), 89.

12 William F. McNeil, Cool Papas and Double Duties (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2001), 110.

13 “Santop makes Record Home Run,” The New York Age, June 12, 1913: 6.

14 James A. Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons: Essays on Baseball’s Negro Leagues, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012), 49.

15 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in his Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012),72-73.

16 “Philadelphia Nationals Lose,” The New York Age, October 9, 1913: 6.

17 Lester, Black Baseball in New York City, 15.

18 Lester, Rube Foster, 83.

19 McNeil, Cool Papas, 110.

20 Wes Singletary, The Right Time: John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Black Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2011), 84.

21 “Royals Land Two Cracks,” Times Union, September 1, 1916: 8.

22 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 44.

23 “Red Sox Allstars win 4-3,” The Boston Globe, September 15, 1918: 13.

24 US Census Record, Draft Registration Card.

25 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14480311/louis-santop-loftin, accessed March 10, 2021.

26 William F. McNeil, Baseball’s Other All-Stars (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2000), 44.

27 “Royals Add to Roster,” New York Herald, May 23, 1919: 17.

28 “Two Homers by Santop…Help the Royal Giants Defeat the Silk Sox,” Passaic Daily News, July 10, 1919: 7.

29 Standard Union, September 30, 1919: 13.

30 Holway, Blackball, 91.

31 Holway, Blackball, 91.

32 Courtney Michelle Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (McFarland 2017), 29.

33 Ribowsky, 110.

34 Ribowsky, 110.

35 Smith, 35.

36 “Santop’s Muff of Dunc’s Foul Gives KC Win,” The Pittsburgh Courier, October 25, 1924: 6.

37 “Darby Magnates Wake Up; Santop Resigned,” The Pittsburgh Courier, March 14, 1925: 7.

38 “Sykes, Henry, and Santop are Released by Hilldale,” The Pittsburgh Courier, July 10, 1926: 14.

39 “Santop’s Bronchos Next For Warders,” Lancaster New Era, June 7, 1928: 22; and “Bacharach Wins Over Bronchos,” Hazelton Plain Speaker, September 8, 1931: 14.

40 Monte Irvin, Few and Chosen: Defining Negro Leagues Greatness (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007), 15.

41 Vibiana Bowman Cvetkovic, (The Story of Commercial) Radio, The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/radio-commercial/.

42 “Louis Santop Dead,” The Chicago Defender, February 7, 1942: 24.

43 Irvin, 15.

44 Fay Young, “Through the Years,” The Chicago Defender, February 7, 1942: 23.

Full Name

Louis Santop Loftin

Born

January 17, 1889 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

Died

January 22, 1942 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.