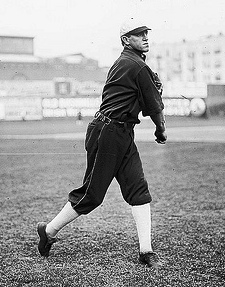

Harry Lord

Another couple of miles west and New Hampshire could have claimed Harry Lord as a New Hampshire native. Porter, Maine – where our guardian of the hot corner was born on March 8, 1882 – is that close to the state line.

Another couple of miles west and New Hampshire could have claimed Harry Lord as a New Hampshire native. Porter, Maine – where our guardian of the hot corner was born on March 8, 1882 – is that close to the state line.

But Mainers take pride in the Porter lad, for Harry Lord was a ballplayer’s ballplayer. Growing up in Kezar Falls, Lord learned an early love of the game, and went on to star in it – and football, as well – at Bridgton Academy. From there it was on to Bates, where he again excelled in both sports. It was at Bates that he first came to consider baseball as a possible career. As Harry explained years later, “As a little chap I played the game, but never with any thought or desire to use baseball as a means of gaining a livelihood. In fact, I had ambitions in other fields. During my high-school baseball days I gave the team the best that was in me, yet I never regarded the game with serious thought until I entered Bates College. There I settled down to study baseball. The further I advanced in baseball the more I saw in the line of making plays. The game interested me beyond the mere physical enjoyment derived.”

The “other fields” that interested Harry were along legal lines. He had planned to be a lawyer. But he also wanted to get married and start a family . . . and he came to believe that he might do better financially on the diamond than in the law office. After further sharpening his skills – and switching from second base to third – playing summer ball in and around South Portland in 1904 and 1905, he accepted an offer from Jesse Burkett to join the Worcester Busters team in the New England League.

Burkett, one of the golden players of the 19th century, was a demanding drillmaster. Harry learned well. He batted .280 and helped Worcester win the league flag in 1906. He advanced to Providence in 1907, again playing a rock-solid third base and hitting a very respectable .278. Up the road, meanwhile, the Boston Americans were rebuilding. The players who had spearheaded them to championships in 1903 and 1904 were either gone or in the process of going. The club’s owner, John I. Taylor, was intent upon finding a replacement at third for the great Jimmy Collins, whom he had traded to the Philadelphia Athletics during the 1907 season. The man he wanted – and got – was Harry Lord.

Harry played the better part of three seasons with the Red Sox, as they renamed themselves beginning in 1908. With the Sox, he developed into one of the game’s premier third basemen. He was of the old school: If he couldn’t stop the ball with his glove he’d stop it with his chest. He gave way to no man on the basepaths either. That included Ty Cobb. In fact, Cobb so respected Lord’s fiercely competitive play – and vice versa, it should be noted – that they became fast friends off the field.

And Harry was no slouch with the bat. In his first full season in the majors, 1908, he contributed a .259 average, 23 steals, and 61 runs scored. The Boston Post wrote: “The crowd alwtook 59ays looks to Lord or Amby McConnell to start something. They generally succeed, too.” In 1909 Harry really came into his own, leading all Red Sox regulars – one of whom was Tris Speaker – with a .315 mark. His stolen base and runs scored counts also increased measurably, to 36 and 89, respectively. The Boston Globe in September honored him by writing, “Harry Lord is by all odds the best run getter among the third basemen of the American League.” Highlights that season, as the Bosox surged to third place, their best showing since the championship year of 1904, included a two-hit performance in the grand opening of Shibe Park (later Connie Mack Stadium) before 32,000 fans on April 12; three hits, three stolen bases, and two runs scored in a 6-1 win over the Senators on April 17; being the lead runner (i.e., the one who steals home) in that rarity of rarities, a triple steal, in a 6-2 win over the Athletics on April 21; fielding in “sensational style” (New York Times) as the Red Sox took their third game in a row from the Browns, 3-2, on June 9; going 4-for-4 in a 9-6 win over the Yankees on June 22; a two hit/two steals/two runs scored game against the Yankees on July 28; knocking out two hits in both ends of a doubleheader sweep of the Tigers on August 3 (before a crowd of 29,781 at the Huntington Avenue Grounds, the most people ever to witness a Boston American League contest to that point); going 3-for-4 with two runs scored in a 5-4 win over the Indians on August 12; again going 3-for-4 as the Sox took Washington, 3-1, on September 9; going 3-for-4 in a 9-7 win over the soon-to-be-champion Tigers on the last day of September; and, to top it all off, being selected team captain in September.

Harry’s .315 average for the season placed him fourth in the league. He was in fast company. Ahead of him were Ty Cobb (.377), Eddie Collins (.346) and Napoleon Lajoie (.324). Behind him were the likes of Wahoo Sam Crawford (.314), teammate Tris Speaker (.309), Home Run Baker (.305), Hal Chase (.283), and an aging Wee Willie Keeler (.264).

Harry, incidentally, took a fair share of abuse for his somewhat craggy looks. During his banner season with the Bosox, 1909, the Boston American went so far as to write, tongue in cheek of course, that “Harry was handsome as a child, according to family history, but the nurse dropped him one day and from that time on he took few prizes at beauty shows.” But could he ever play third!

After his superlative 1909 season the sky seemed the limit for Porter, Maine’s, contribution to baseball. An injury to his hand, though, changed all that in 1910. On July 1, batting in his customary number two slot in the Red Sox attack in a game against the Senators, Harry was whacked on the hand by a Walter Johnson fastball. Ouch! Actually, double ouch: The Big Train’s fastball was so fast it was once said, “He can throw a lamb chop past a wolf.” Harry’s finger was broken. It took him but two weeks to mend well enough to get back into the lineup, but it was still long enough for management to seemingly become enamored of Clyde Engle, the man who’d filled in for the two weeks. Harry was inserted back into his old position for a week, then benched in favor of Engle. On August 9 he was traded to the White Sox along with second baseman Amby McConnell for pitcher Frank Smith and third baseman Billy Purtell. Delighted to be playing again, Harry batted a healthy .297 in 44 games for the White Sox over the rest of the season.

Harry had a somewhat controversial career with the White Sox. An acknowledged team leader (he was once more selected to be captain), excellent fielder, and batsman, he resented owner Charlie Comiskey’s parsimonious ways. (Comiskey’s tight-fisted policies, history now accords, were the primary cause of the Black Sox scandal of 1919.) Harry, however, hung in there … and strung together three strong seasons for the Pale Hose. His numbers for 1911 were especially impressive: 180 hits in 561 at-bats for a .321 average, 43 stolen bases, and 103 runs scored. By 1914, though, Harry had had it with Comiskey. His salary requests were seldom met. His manager, Nixey Callahan, was a conservative sort whose goal was to downplay the fiery brand of ball so espoused by Harry. What really did it, however, was when he was told that hit or take signals would be flashed to him from the sideline when he was at bat. After but 21 games into the season, he asked for and was granted his release, and left the team.

After sitting out the remainder of the summer of 1914, Harry went aboard the Federal League, the “outlaw” third major league that existed for two years, 1914-1915. Two months into the season (actually, Harry joined the team as a player on May 24; was made manager two weeks later, on June 5), he was signed as player-manager by Buffalo. When he joined them the team, known alternately as the Buffeds or the Blues, were mired in last place – with a 15-30 record – and seemed destined to remain there. Harry, though, stirred them up, got their juices flowing, and got them to begin winning.

Under his reign the club – referred to as “Harry Lord’s fighting Federal League team” – took 60, lost 48, and moved up to a relatively strong sixth-place finish. That the fans of the Niagara Frontier appreciated his work was shown on August 7: It was Harry Lord Day at the ballpark, a fitting tribute to Harry’s tenacity and leadership.

After the demise of the Federal League, Harry came home to New England. He managed and held down third base for the New England League’s Lowell Grays in 1916. The following year he was with Portland in the Eastern League, batting .266 in 102 games, and in 1918 he managed in Jersey City.

Harry then tried his hand in the grocery business: He purchased a store in South Portland, close to his home in Cape Elizabeth. It afforded him plenty of time to do one of the things he enjoyed most: share life with his wife and his son and daughter. He loved to hunt and fish, too. He also kept close to the game. He coached at South Portland High, was player-manager of a semipro team, later managed a spirited Dixfield nine. In 1925 Harry went into the coal business as co-proprietor of the Portland Lehigh Coal Company. He remained in that work the rest of his life.

After several years of a lingering illness, the great old third baseman passed away in Westbrook on August 9, 1948. His one regret: that he had exited the White Sox before the Black Sox infamy of 1919. He was a leader among the Sox players, was trusted by them. “I’m sure,” he voiced in his later years, “that if I could have been there, Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver, whom I still don’t believe were in it, and the others would have listened to me. I could have stopped it if I’d had to punch the ringleader in the nose.” And that’s probably exactly what Harry Lord, if that’s what it would have taken, would have done.

Sources

This biography originally appeared in Will Anderson’s self-published 1992 book Was Baseball Really Invented in Maine? and is presented here with the author’s permission. Bill Nowlin has added new material and slightly revised the original version.

Full Name

Harry Donald Lord

Born

March 8, 1882 at Porter, ME (USA)

Died

August 9, 1948 at Westbrook, ME (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.