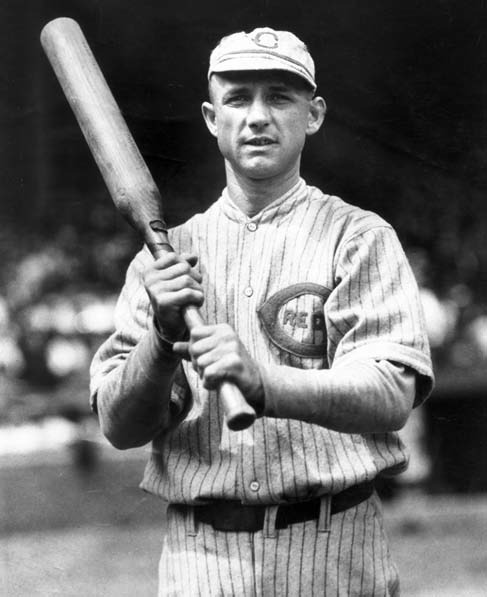

Heinie Groh

Heinie Groh was undoubtedly the National League’s best third baseman of the Deadball Era. Historian Greg Gajus suggests that Groh would have won at least one Most Valuable Player award (for the 1919 season) and perhaps two others (1916 and 1918), and that eight of his 12 full seasons were of All-Star quality. Furthermore, contemporaries considered him the NL’s best-fielding third baseman, so he likely would have added at least a half-dozen Gold Gloves to his trophy case.

Heinie Groh was undoubtedly the National League’s best third baseman of the Deadball Era. Historian Greg Gajus suggests that Groh would have won at least one Most Valuable Player award (for the 1919 season) and perhaps two others (1916 and 1918), and that eight of his 12 full seasons were of All-Star quality. Furthermore, contemporaries considered him the NL’s best-fielding third baseman, so he likely would have added at least a half-dozen Gold Gloves to his trophy case.

While his defense was important, Groh’s feats at the plate made him a star. Positioning himself at the extreme front of the batter’s box with both feet facing the pitcher, he choked up on his peculiar bottle bat and slapped at the ball. Taking advantage of his size (5-feet-6, 160 pounds) to create a small strike zone and draw a lot of walks, Groh also became adept at bunting and executing the hit and run. He led the NL in walks in 1916, in hits in 1917, and in runs scored in 1918. Groh also led the league in doubles twice, and had a batting average of .298 or better each year from 1917-21.

Henry Knight Groh was born in Rochester, New York, on September 18, 1889. Turning down an opportunity to attend the University of Rochester, Groh signed with Oshkosh of the Wisconsin-Illinois League in 1908. He played shortstop and batted a mere .161, an average he remembered to the last decimal point—in spite of a failing memory—when interviewed more than a half-century later by Larry Ritter for The Glory of Their Times. Groh batted .297 in back-to-back seasons at Oshkosh in 1909-10 (“I kept practicing and practicing at it, and the next year I hit about .285, and the year after that I made it to .300,” was the way he remembered it), after which the New York Giants purchased his contract. In 1911 the Giants assigned Groh to Buffalo of the Eastern League, where he batted .333 and earned a promotion to the big city for 1912.

Heinie Groh’s major league debut as a pinch-runner against Brooklyn on April 12, 1912, was a memorable one. The umpire was Bill Klem, who had a long-running feud with Giants manager John McGraw. As the small and boyish-looking Groh made his way onto the field at the Polo Grounds, a voice from the opposing dugout yelled, “McGraw’s sending in the batboy to show you up, Bill.” The entire grandstand heard the voice and most of them believed it. Klem glared at the kid and asked, “Are you under contract with the New York club?” “I am,” replied Groh. The umpire let him take his place at first base, but some fans left that day thinking they’d seen the batboy.

Groh earned a spot as the Giants utility infielder in 1912 but didn’t get much playing time, appearing in just 27 games and batting .271 for the NL champions. That year McGraw suggested that the diminutive infielder might become a better hitter if he used a bat with a bigger barrel. The problem was that Groh’s hands were too small to grip such a bat, so he asked Spalding Sporting Goods to customize a bat for him. Most bats were gradually tapered from the barrel to the handle, but the bat Spalding created for Heinie had an unusually thick barrel and an unusually thin handle, with an abrupt taper in between. As Groh told Ritter, “We whittled down the handle of a standard bat, and then we built up the barrel, and when we were finished it looked like a crazy sort of milk bottle.” Thus was born the bottle bat, an innovation that will forever be associated with Heinie Groh.

Desperate for pitching, the Giants traded Groh to the Cincinnati Reds on May 22, 1913, along with pitcher Red Ames, outfielder Josh Devore, and $20,000 in cash, for infielder Eddie Grant and pitcher Art Fromme, who was coming off a 16-18 season with a 2.74 ERA. Groh’s inclusion was an afterthought but he turned out to be the key player in a lopsided deal for the Reds. The move gave him an opportunity to play every day and he soon entrenched himself as Cincinnati’s leadoff hitter and starting second baseman. In 1915 the Reds moved Groh to third base, which may have been the most important position on the infield during the bunt-crazy Deadball Era. “I’d get in front of that ball one way or the other,” Heinie said, “and if I couldn’t catch it I’d let it hit me and then I’d grab it on the bounce and throw to first.” Groh’s .967 career fielding average is the best for any third baseman that played before 1920.

With Edd Roush batting ahead of him and Jake Daubert batting behind him in the order, Groh enjoyed his finest season in 1919, ranking among the league leaders in virtually every category to lead the Reds to their first NL pennant. Groh didn’t play particularly well during the 1919 World Series, but his teammates did and the Reds captured their first World’s Championship. The celebration was tainted by allegations that the White Sox might have lost intentionally, as part of a conspiracy with gambling interests. Groh was one of the first to speak out against the idea of a fix, saying he didn’t see anything suspicious. After the plot was confirmed, his only comment was, “I think we’d have beaten them either way.”

Two years later, Groh became embroiled in a bitter salary dispute with Reds owner Garry Herrmann. Several players held out, including Roush and pitcher Ray Fisher, to protest what they thought were outrageously low salaries. Roush returned on May 1. Fisher elected to take over as baseball coach at the University of Michigan. Groh, however, vowed never to rejoin the Cincinnati club. To resolve the impasse, Groh and the Reds worked out an agreement under which he would sign a contract and be immediately traded back to the New York Giants. Fearing an “unhealthy situation if a dissatisfied player could dictate his transfer to a strong contender before he agreed to sign a contract,” Commissioner Landis voided the deal and ruled that Groh could play only with the Reds for the remainder of the season. While Landis insisted that this ruling should not be regarded as establishing a precedent, in fact it did.

Nobody liked this solution—not the Reds; not the Giants; and certainly not Heinie Groh. Once the season ended, the parties finally gained some measure of satisfaction by consummating the trade, and Groh re-joined John McGraw’s Giants a decade after he had started his big-league career with that team. His batting average plummeted to .265 in 1922, the lowest of his career to that point and 66 points below his average of the previous season. Once the postseason started, though, Groh’s bottle bat came alive. He hit in each of the five games, finishing with a Series-best .474 batting average as the Giants swept the New York Yankees. From that point on, Heinie’s Ohio license-plate number was 474.

Groh was a key member of a Giants team that won three straight NL pennants (four, including the year before Groh arrived), but that decisive victory in 1922 was their only World Series win while Groh was there. They lost to the Yankees in 1923 and to the Senators in 1924. Late in the 1924 season, Groh suffered a serious knee injury. He was replaced at third base by 19-year-old Freddie Lindstrom, who eventually wound up in the Hall of Fame. Groh was 35 by then and never again able to play regularly because of the knee. He spent the next two years with the Giants as a seldom-used infielder. In 1927 Groh ended his career with Pittsburgh, playing only 14 games during the regular season and making his final big-league appearance as a pinch-hitter in the 1927 World Series.

When his playing days were over, Groh stayed in baseball, first as a minor league manager and later as a scout. He eventually returned to Cincinnati where he worked as a cashier at River Downs Race Track. Groh was 78 when he died of a respiratory ailment on August 22, 1968.

Author’s Note

A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

Allen, Lee. The Cincinnati Reds. Putnam, 1948.

Baseball the Biographical Encyclopedia. Total Sports Publishing, 2000.

Baseball Magazine Archives

“Big League Ball Player Wields New Style Bat”. Popular Mechanics, July 1920.

“Cincinnati’s All Time Best”. Sport. January 1958.

Rhodes, Greg and John Snyder. Redleg Journal. Road West Publishing, 2000.

Ritter, Lawrence. The Glory of Their Times (Groh interview). Quill, 1984.

The Sporting News Archives

Total Baseball (6th edition). Total Sports Publishing, 2001.

Full Name

Henry Knight Groh

Born

September 18, 1889 at Rochester, NY (USA)

Died

August 22, 1968 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.