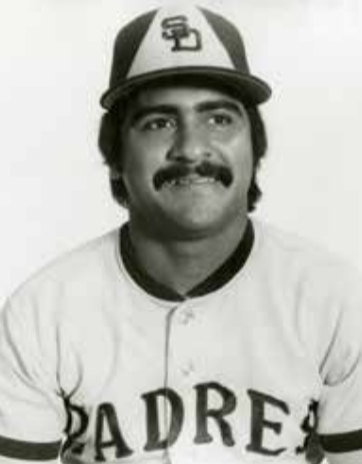

Jerry Morales

“WHO’S Jerry Morales?”

“WHO’S Jerry Morales?”

This question began an article in the Chicago Tribune on November 13, 1973, about the previous day’s trade by the Cubs of four-time All-Star Glenn Beckert to the San Diego Padres for Morales. That simple inquiry “was the prevalent reaction” as word of the trade spread, according to influential Trib sportswriter Richard Dozer. Dozer characterized Beckert’s roommate on road trips, nine-time All-Star Ron Santo, as being disappointed. “They’re breaking up that ol’ gang of ours,” Santo said.1

That old gang was beloved, and the low expectations of the Padres during their first five years of existence couldn’t have prepared Morales for becoming one of the substitutes in Chicago. Soon after their loss in the 1945 World Series, the Cubs barely managed one winning season in a 20-year span, but from 1967 to 1972 they were contenders and finished in either second or third place. Their manager was quotable Hall of Famer Leo Durocher and Santo was one of four future Hall of Famers in the field. Beckert was one of four other players to represent the Cubs at All-Star Games during that era.

The Cubs didn’t overhaul their team in a single offseason, and more than a year after the Beckert trade, their manager still felt there was too much pressure on Morales and other recent arrivals. “This is a new beginning, not an extension of the past,” said Jim Marshall, who took the reins from Whitey Lockman in mid-1974. “I want Cub fans to know these young men for who they are … not as replacements for stars of the past.” Tribune sportswriter Rick Talley said Marshall had chosen his words carefully, and that they were “directed toward the press and fans of Chicago. He wants us, finally, to forget about Ferguson Jenkins, Ernie Banks, Ron Santo, Ken Holtzman, Glenn Beckert, Bill Hands, Billy Williams, Randy Hundley and all the others.”2

Before reviewing how Jerry Morales responded as a Cub, it seems fitting at this point to first answer that initial question: Who’s Jerry Morales?

Julio Rubén Morales y Torres was born on February 18, 1949, on Calle Cristobal Colon (Christopher Columbus Street) in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, a city of about 30,000 near the island’s southeastern coast. Yabucoa is nicknamed the City of Sugar because its valley was known for growing sugar cane, and that inspired the name of the local amateur baseball team on which Jerry eventually played. He spent his early years living in public housing named after a Dr. Victor Berrios.3 Morales’ father was a government health inspector, and Jerry was the third oldest of four children.4

Jerry played Little League baseball growing up, and on his way to graduating from Yabucoa’s Teodoro Aguilar Mora High School he ran track and captained the school’s baseball team.5 In 1963 he had the opportunity to see the AL pennant winners, the New York Yankees, play an exhibition game in Puerto Rico.6 When Jerry was 14 or 15 he received important instruction from a legendary major leaguer from Puerto Rico. Roberto Clemente “came to my hometown for a clinic. I remember everything, particularly the things he taught me about playing the outfield. It helped me my whole career,” Morales recalled more than two decades later. “He showed me the way to throw the ball, and the way to catch it, and the best way to hit the cutoff man, and he taught me how to learn to anticipate where the ball would come.”7

At the age of 16 Jerry played amateur baseball for the Yabucoa Azucareros.8 Around that time he also played in Cidra, a city west of Yabucoa and south of San Juan. He and future major leaguer Ed Figueroa were on a Cidra squad that won the championship in a league named for Hiram Bithorn, the first Puerto Rican to play in the majors.9

A very momentous month for Morales was June of 1966, when he was 17 years old. He and Figueroa were on the Puerto Rican national team that won a silver medal at the 10th quadrennial Central American and Caribbean Games, held in San Juan. Puerto Rico lost only to Cuba, the gold medal winner in baseball.10 Morales made quite an impression in the games, because scout Nino Escalera swiftly signed him to a contract with the New York Mets.11 He reportedly received a signing bonus of $21,000 and used it to buy his mother a house.12

Morales made an immediate impact for the rookie league Mets in tiny Marion, Virginia. On July 24 he was leading the Appalachian League in batting with a .446 average, far above the .400 mark of runner-up Richie Hebner of the Salem Pirates13 (for whom Morales would be traded after the 1979 season). Morales soon won a gold wristwatch from the Topps Chewing Gum Company when the baseball-card company named him the Appalachian League Player of the Month for July. He finished the month with an average of .414 and 21 RBIs in 21 games.14 Hebner ended the season with the league’s highest batting average but Morales was the only regular who reached base more than half the time (.527 on-base percentage), and it was Morales who was chosen by the league’s managers and sportswriters as the most outstanding player.15

During the subsequent offseason Morales played in Puerto Rico’s winter league on the Caguas Criollos. His manager was former Milwaukee Brave John “Red” Murff, and coaching was the aforementioned Nino Escalera. Teammates included Félix Millán (also from Yabucoa), Willie Montañez, and Ron Swoboda.16 As much as Morales learned at age 15 from Roberto Clemente, it was Vic Power whom Morales credited with helping him develop the most, as his manager in a later winter-league season.17 Morales ultimately played in the league for 18 winters.18

In 1977 Morales explained why he returned to Puerto Rico regularly in the fall. “I wanted to be with my people, and to speak Spanish and not have any trouble and know what places I can go,” he said. When he played for Marion, he knew almost no English. “I knew what was a hamburger and a hot dog, but I wanted something else,” he recalled. “My roommate and I finally learned how to order liver and onions.” They ate liver for several consecutive days. Strongly missing Puerto Rico wasn’t something that subsided quickly. “My first three, four years in pro ball, I was always looking for the last day of the season to go home,” he admitted.19

At least he had frequent contact with Figueroa during his second and third years as a pro up north. They were teammates briefly with Marion, which employed Figueroa as a starting pitcher for two games, but the two spent all of 1967 together with the Winter Haven Mets of the Class-A Florida State League. “Jerry Morales was my best friend on the team,” Figueroa said. “We had a nice apartment by a lake and it was a good place to live.”20 They were teammates one more time with Raleigh-Durham for part of 1968.

Morales played in 139 out of Winter Haven’s 140 games. His batting average plunged almost 100 points from a year earlier, to .248, but he demonstrated considerable speed with 14 triples plus 27 stolen bases in 31 attempts. Despite Morales’ mediocre batting average, he was one of seven Winter Haven players promoted to New York’s 40-man roster on October 20.21 As a result, he spent spring training in 1968 with big leaguers, and a four-day stretch was probably most memorable: On March 8 he saw Tom Seaver hit in the head by a line drive during practice, on March 9 he saw Tommie Agee hit in the head by a pitch from Bob Gibson, and on March 10 his clutch eighth-inning hit drove in Bud Harrelson for his team’s only run in a 14-inning tie against the Cardinals.22 On March 11 his walk with the bases loaded in the 11th inning won a game against the Astros.

For the regular season, however, it was back to Class-A baseball for Morales. He split the year between Raleigh-Durham in the Carolina League and Visalia in the California League. His statistics weren’t much different than in 1967, and the Mets left him unprotected for the expansion draft on October 14, 1968. The Padres made him their eighth selection.

Morales spent most of 1969 with the Padres’ Elmira, New York, team in the Double-A Eastern League. He had a particularly memorable game on May 6, when his speed kept him from hitting for the cycle: Instead of a homer, triple, double, and single, he had a homer, two triples, and a single.23 In 127 games he reached new heights in home runs, RBIs, and total bases while batting .272. He was promoted to the parent club, and made his major-league debut in San Diego on September 5, 1969.

In that game, the Padres were leading the Dodgers by three runs in the bottom of the eighth inning. Left fielder Al Ferrara singled with one out, and Morales ran for him. He was soon erased on an inning-ending double play. Morales took over in left field but the Dodgers were retired quietly in the ninth inning without a ball hit to him. The next day he entered the game under similar circumstances except that he was put out trying to steal, and he at least got to touch the ball in the ninth inning when he fielded a Dodger single. In his third consecutive game against LA, he ran for Ferrara in the seventh inning and scored his first run as a major leaguer, then recorded his first putout in the eighth. He didn’t play on September 8 but the next day he batted second in the starting lineup, in Houston. He played center field and enjoyed his first major-league hit, a single, in the top of the ninth inning. In Cincinnati on September 10, he batted third and played right field. In the fourth inning he homered for the first run of the game, and the Padres ended up winning, 2-1. All told, Morales played in 19 games for the Padres that month and hit .195.

Morales was the Opening Day left fielder in 1970 for the Padres and played in 28 games during the season’s first five weeks. He batted only.155 and on May 12 was shipped to Triple-A Salt Lake City for the remainder of the season. In 1971 Morales played for Triple-A Hawaii until early September, and was then called up for 12 games by the Padres. His big-league batting average declined again, to .118. His 1974 Topps baseball card noted that he led PCL outfielders in fielding percentage in 1970 and 1971, but his minor-league batting stats weren’t exactly impressive. Still, he didn’t play in the minors again for more than a decade.

In 1972 Morales was the Opening Day center fielder for the Padres and throughout the season was one of five San Diego outfielders who played regularly. He wasn’t in San Diego’s starting lineup on Opening Day in 1973 but during the course of the season he was one of four regular outfielders. The one constant during his five seasons with the Padres was that the team finished last in the six-team NL West. At least things started clicking for Morales personally in 1973, at age 24, when he hit .281 in 122 games. Thus, the Cubs offered Beckert (plus minor leaguer Bobby Fenwick) to the Padres in trade for Morales after that season.

About six weeks into the 1974 season, Morales made a big splash against the team that drafted him with a six-RBI game in New York on May 22. He homered off Tom Seaver in the fourth inning and collected a two-run single as well. After eight innings the score was tied, 6-6. With a Cub on third base and one out in the ninth inning, the Mets elected to walk Rick Monday intentionally to bring up Morales. His homer into the left-field bullpen produced the final score, 9-6. “This had to be my biggest game of my major-league career,” Morales said at the time.24 Morales batted .273, and though his 15 homers were only third highest among Cubs that season, his 82 RBIs topped the team. Morales scored 70 runs, the highest total of his major-league career. On the downside was a particularly ugly pair of numbers: Morales had two stolen bases but was caught stealing 12 times.

Jerry Morales was still only 26 years old at the start of the 1975 season. “Morales has the marking of a future star and maybe even a super star,” wrote Ulish Carter in the spring of 1975 in the New Pittsburgh Courier.25 Morales’ production that year didn’t contradict such optimism: He hit .270 and drove in 91 runs, the best mark of his career. The second highest total by a Cub that year was 70, by Manny Trillo. What’s more, no other Cub had that many RBIs during the six seasons from 1973 through 1978.

During the first half of 1976, Morales was in the headlines for an unusual reason. On the last weekend of May he and a friend, off-duty Chicago police officer Frank Ramirez, paid a late-night visit to a taco stand on Chicago’s northwest side, and as Ramirez drove Morales back to the latter’s apartment building, four young men followed them after having felt that Ramirez cut them off in traffic at some point. The four men attacked Ramirez and Morales when they saw their chance but the doorman at Morales’ building summoned on-duty officers, who arrested the quartet. Both victims suffered back injuries and Morales (whose weight on Topps cards had been listed as just 165 pounds as recently as 1974) also was cut on the head. He missed a few games as a result.26 In August Morales was hospitalized with muscle spasms in his back,27 which caused him to miss 13 games, and the team’s media guide for the next season said this was one reason his total RBIs declined to 67.28 Nevertheless, his total of 16 homers was his personal best as a pro.

Relative to other outfielders, Morales’ defensive performance peaked during 1975 and 1976. His 11 assists in 1975 were second best among NL right fielders, and his 12 in 1976 were third best. In 1975 he had the fifth best range factor among NL right fielders. In 1976 he initiated the most double plays among NL outfielders, with six. His .980 fielding percentage in 1975 was fourth best among NL right fielders and his .982 mark in 1976 was third.

Morales was known for preferring to make basket-style catches of fly balls, with both hands at his waist, and once dispensed detailed advice on how to break in a new glove. He needed to do that before the 1977 season because he and a few teammates had their gloves stolen during spring training. (Bill Buckner lost five.) “I take a new glove and beat it with a bat until I get it the way I like it,” said Morales. “Then I tie it up with string and soak it in water for a day or two. I’ll put a little oil on it, but not too much, because I don’t want to make it too heavy.” (He admitted that he wasn’t using gloves made by the company with which he was under contract but added, “As long as they don’t find out I think I’ll be okay.”)29

By 1977, Morales had developed a reputation as a clutch hitter. “This is our best man in the clutch,” José Cardenal said of Morales about two months into the season.30 Sportswriter Jerome Holtzman generalized later that season in The Sporting News that “so far as the Cub players are concerned Morales is Mr. Clutch.”31 Stats for the previous year back up this assessment: The baseball-reference.com “Splits” web page for Morales shows that in “late and close” situations Morales batted .360 and had an on-base percentage of .400.32

By the 1977 All-Star break, Morales was hitting .331, best in the NL. This happened in the midst of an impressive first half for Chicago. On June 28 they peaked at 47-22 with a lead of 8½ games in the National League East. NL All-Star manager Sparky Anderson chose Morales and three other Cubs as All-Stars, and that was the only time he received that honor.

The game was played in Yankee Stadium on July 19. Morales entered the game in the bottom of the sixth inning replacing starting center fielder George Foster. An inning later he made his only putout, and in the top of the eighth he batted against Sparky Lyle with a teammate on second base. Lyle hit him on the left knee.

“I was lucky,” Morales said shortly afterward. “If Lyle’s pitch had hit the kneecap, forget it! It’d have been busted.” Bob Kennedy, general manager of the Cubs, said he “almost had a heart attack” when he saw where the stray pitch landed.33 Lyle then threw a wild pitch to Dave Winfield. Morales’ knee must not have been bothering him too much because he remained in the game and scored from second base when Winfield singled.

Robert Markus of the Chicago Tribune grumbled after the game that Cub All-Stars Morales, Manny Trillo, and Rick Reuschel were mostly ignored by sportswriters, who “hovered about Tom Seaver, Joe Morgan, and Steve Garvey.” Markus was particularly defensive of Morales, who he said wasn’t “an effusive talker.”34 Holtzman, of the Chicago Sun-Times, was of like mind, and took advantage of an opportunity early the next month to talk up Morales in The Sporting News.

Holtzman implied that fans may have noticed Morales on television even if they didn’t know his name. “Morales has an unmistakable batting stance. He keeps his feet wide apart and holds the bat over his head,” Holtzman wrote. “This unusual stance, he insists, enables him to wait longer on the pitch.”35

The Cubs collapsed during the second half of the 1977 season and finished 81-81. Meanwhile, Morales’ batting average regressed somewhat and he finished at .290, but that was the highest mark of his career. He also finished with 34 doubles, the most of his big-league career by far.

GM Kennedy presumably felt that Morales’ trade value would never be higher, and on December 8, 1977, he sent Morales, catcher Steve Swisher, and cash to the Cardinals for catcher Dave Rader and outfielder Héctor “Heity” Cruz. This occurred about six weeks after the Cubs traded the very popular Cardenal to the Phillies. Chicago’s Latino community was very upset by the two trades, according to Julio Montoya, associate editor of the Chicago weekly newspaper La Raza. “The reputation of the Cubs was very bad in the community,” he said in 1980. “But, at first, it seemed like they still kept going out to the ballpark, to see if the Cubs could win without Morales and Cardenal.”36

Morales played in 130 games for the Cardinals but his batting average slumped to .239. About a year after they traded for him, St. Louis dealt Morales and pitcher Aurelio Lopez to the Tigers for pitchers Bob Sykes and career minor leaguer John Murphy. In Morales’ 15 years as a major leaguer, 1979 was the only time he played for a winning team. Still, Detroit’s record of 85-76 was only good enough to finish fifth in the AL East. His batting average slipped even more, to .211, and on October 31 he and Phil Mankowski were traded to the Mets for Richie Hebner. Morales played only one season for the team that originally drafted him. His batting average rebounded somewhat, to .254, but he was now a part-timer. He returned to the Cubs for three more seasons, 1981-1983, and in the first two of those seasons of limited duty his average returned to his peak levels, at .286 and .284.

Morales was single when he first became a Cub but by the time he ended his playing career with them he was married to the former Carmen Lourdes Hernández.37 His last game in the majors was a loss at home to the Phillies on September 28, 1983. As a pinch-hitter, he lined out. Morales concluded his major-league career with a .259 batting average.

The Cubs kept Morales in their organization through 1986 as minor-league hitting coordinator and a roving instructor for outfielders. He then served as a Puerto Rican scout for the Dodgers from 1987 through 1990. During the winter from 1986 to 2002 he was a fixture as a coach in the Puerto Rican league. He was elevated to San Juan’s manager for 1999-2000.38

The strike by major-league players in August of 1994, which ended up canceling the World Series, motivated many Puerto Rican major leaguers to play in their native island’s winter league season. As a result, San Juan Senadores manager Luis “Torito” Melendez had an incredibly difficult time choosing among many worthy candidates to represent Puerto Rico on its 1995 Caribbean Series team. Morales was one of four coaches who helped Melendez make those choices. The resulting “Dream Team,” which won the Series, included Hall of Famer Roberto Alomar, Edgar Martinez, Juan Gonzalez, Bernie Williams, Ruben Sierra, Carlos Baerga, and Carmelo Martinez.39

Morales limited his baseball work to Puerto Rico through early 2002 in order to raise his children but then took a coaching job with the Montreal Expos because making a living through the winter league was proving to be difficult, and he felt his children were old enough to cope with their father being away for long periods.40 For three years Morales coached first base for the Expos and also coordinated the defensive positioning of their outfielders. He was with the Expos until 2004, the franchise’s final season before it relocated to Washington.41 He resigned so that he could spend much more time with his wife, who was battling lupus.42 He returned to the mainland as a minor-league instructor for the Mets in 2006,43 and was the first-base coach for the Washington Nationals in 2007 and 2008.

In early 2009 the Mets signed Morales as a coach for their St. Lucie team in the Florida State League,44 but first he was committed to helping coach the Puerto Rican team in the 2009 World Baseball Classic in March.45

Things came full circle for Jerry Morales in the spring of 2015, when his hometown of Yabucoa named its municipal gymnasium after him, and he took part in a ceremony that made the new name official.46 The facility includes a large sign with biographical information about him, along with many life-size photos spanning his life in baseball. He can rest assured that plenty of residents can easily answer the question, “Who’s Jerry Morales?”

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Richard Dozer, “Beckert Goes to San Diego,” Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1973: Section 3, Page 1. Dozer had chaired the Chicago Baseball Writers Association three years earlier and became president of the Baseball Writers Association of America three years later.

2 Rick Talley, “Marshall Asks Cub Fans to Forget ‘Stars of Past,’” Chicago Tribune, January 17, 1975: Section 4, Page 3.

3 The street of his birth and early home are identified on a public plaque honoring him in Yabucoa, visible in several sources, including “Bautizan con el nombre Julio Rubén ‘Jerry’ Morales Gimnasio Municipal de Yabucoa,” La Esquina (Maunabo, Puerto Rico), May 2015: 36.

4 Walter L. Johns, “San Diego’s Jerry Morales,” Cumberland (Maryland) News, March 28, 1970: 12.

5 1977 Chicago Cubs News Media Guide, 20.

6 Robert Markus, “He’s Top NL Hitter, but Morales Still Ignored,” Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1977: Section 4, Page 3.

7 Pohla Smith, “Clemente Sons Choose Non-Baseball Careers,” Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1987; 15. Morales told Pohla Smith that he was 15 at the time, but a decade earlier he said that happened when he was “about 14.” See Jerome Holtzman, “Bat Speaks Volumes for Quiet Morales,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1977: 5.

8 “Bautizan con el nombre.”

9 “Breve historia del béisbol en Cidra 1962-1968,” Periódico La Cordillera (Cidra, Puerto Rico), August 27, 2009; see lacordillera.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=288:breve-historia-del-beisbol-en-cidra-1962-1968&catid=43:columnistas&Itemid=110.

10 See baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1966_Central_American_and_Caribbean_Games_(Rosters) and baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1966_Central_American_and_Caribbean_Games.

11 “Young Outfielder Contracted by Mets,” Schenectady (New York) Gazette, June 28, 1966: 24.

12 Johns.

13 “Morales Holds Appy Lead,” Bluefield (West Virginia) Daily Telegraph, July 31, 1966: 12.

14 “Stroud, Pepper Capture Third Topps Citation,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1966: 33.

15 “Morales Named Top Player in Appalachian’s Balloting,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1966: 36.

16 “Puerto Rican Squads,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1966: 41.

17 Johns.

18 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1995), 105.

19 “Quicksand of Anonymity Bothering Jerry Morales,” Independent Record (Helena, Montana), June 2, 1977: 17.

20 Dave Klein, On the Way Up: What It’s Like in the Minor Leagues (New York: Julian Messner, 1977), 89.

21 “Mets Send 6 Players to Farm,” Troy (New York) Record, October 21, 1967: 17.

22 “Mets, Cards Knot, 1-1,” Playground Daily News (Fort Walton Beach, Florida), March 11, 1968: 7.

23 Ken Rappoport, “York’s Angel Bedevils Yankees, 8-5,” Nashua (New Hampshire) Telegraph, May 7, 1969: 18.

24 “Morales Slaps Six RBIs in Cub Win over Mets,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal Standard, May 23, 1974: 15.

25 Ulish Carter, “Cubs No Longer Floor Mats,” New Pittsburgh Courier, May 3, 1975: 9.

26 “Hearing Set in Morales Case,” Arlington Heights (Illinois) Herald, June 3, 1976: Section 2, Page 2.

27 “Bench, Foster ‘Solos’ Rock Burris, Cubs 4-3,” Chicago Tribune, August 21, 1976: Section 2, Page 1.

28 1977 Chicago Cubs News Media Guide, 20.

29 Roger Farrell “Breaking in That Glove? Give These Methods a Try,” Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois), April 30, 1977: 7.

30 “Quicksand of Anonymity.”

31 Holtzman.

32 See baseball-reference.com/players/split.fcgi?id=moralje01&t=b&year=1976. The 1977 Chicago Cubs News Media Guide (Page 5) stated that “Jerry had a .322 on-base percentage, seventh on the team. However, in a clutch situation, this intelligence stat soars to a .469 which is by far the best for the Cubs.” It is unclear how the media guide defined “a clutch situation.”

33 David Condon, “Morales Glows in Cub Sky,” Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1977: Section 2, Page 1.

34 Markus.

35 Holtzman.

36 “¡Béisbol!,” Fred Mitchell, Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1980: Section 6, Page 1.

37 Ned Colletti, Sharon Pannozzo, and Bob Ibach, 1983 Chicago Cubs Media Guide (Chicago National League Ball Club Inc.), 54.

38 “Nationals Manager Manny Acta Names 2007 Coaching Staff,” MLB.com, November 21, 2006; washington.nationals.mlb.com/content/printer_friendly/was/y2006/m11/d21/c1744911.jsp.

39 Gabrielle Paese, “Remembering the ’95 ‘Dream Team,’” ESPN.com, February 1, 2015; espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/12263157/remembering-puerto-rico-1995-caribbean-series-dream-team.

40 Harvey Araton, “Puerto Rico: No Longer an Island of Dreams,” New York Times, April 13, 2003: SP7.

41 “Nationals Manager Manny Acta.”

42 Bill Ladson, “Nationals to Interview Coaches,” MLB.com, December 10, 2004; washington.nationals.mlb.com/content/printer_friendly/was/y2004/m12/d10/c920268.jsp.

43 Barry Svrluga, “Acta Fills Out Nationals’ Staff,” Winchester (Virginia) Star, November 22, 2006: C2.

44 “Transactions,” Northwest Florida Daily News (Fort Walton Beach, Florida), February 4, 2009: C2.

45 “World Baseball Classic,” The Sun (Yuma, Arizona), March 3, 2009; D3. See also asapsports.com/show_interview.php?id=54816, March 9, 2009.

46 “Bautizan con el nombre.”

Full Name

Julio Ruben Morales Torres

Born

February 18, 1949 at Yabucoa, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.