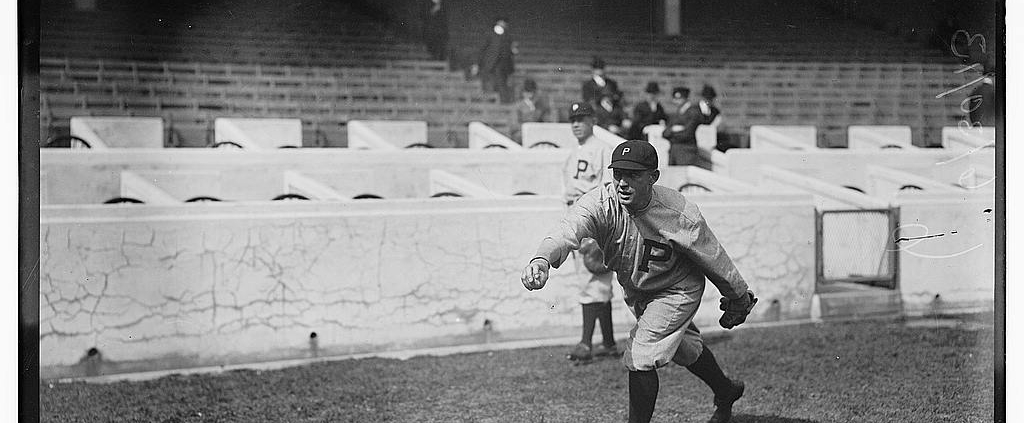

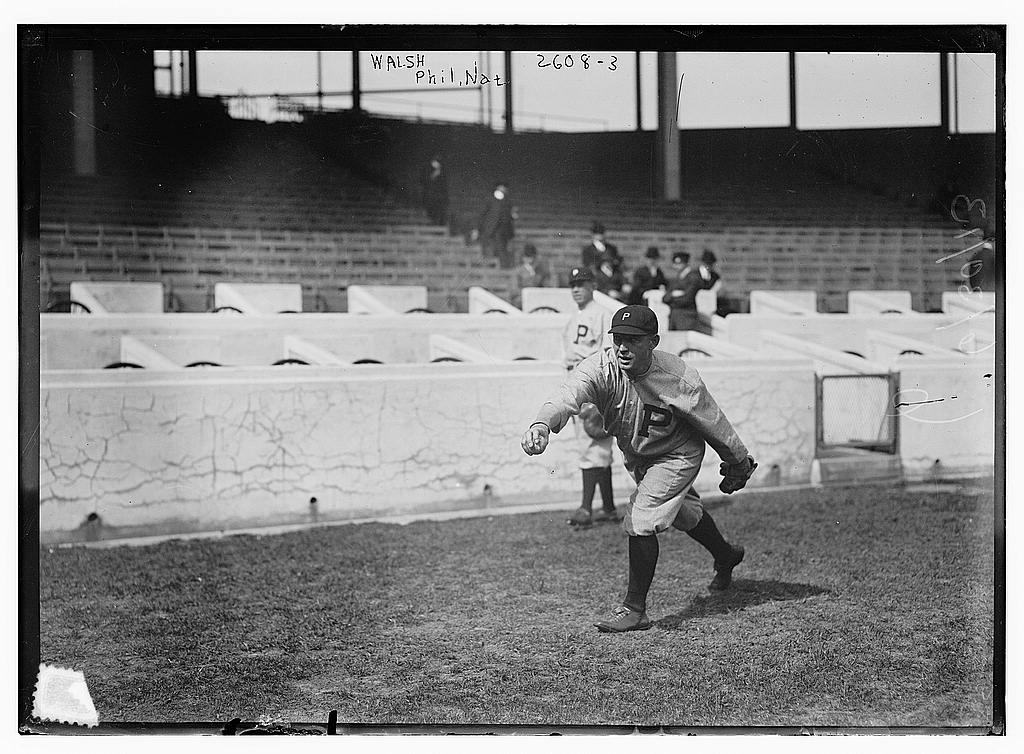

Jimmy Walsh

Playing with the Philadelphia Phillies from 1910 through 1913, Jimmy “Runt” Walsh became one of the most notable utility players of his era. In 1911 he became the third major leaguer to that point to play every position during a single season.1 Recruited by his ex-Phillies teammate Otto Knabe, the colorful Walsh jumped to the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins after the 1913 season. Playing regularly at third base, Walsh emerged as the Terrapins’ finest slugger. Yet, like many others who jumped, he did not return to the majors when baseball peace came after the 1915 season.

He was born Michael Timothy Walsh on March 25, 1886, in Lima, Ohio. His parents, Michael and Margaret Walsh, emigrated to America from Ireland, and he was the youngest of their eight children. As his mother managed the large household, his father worked as a machinist.

Of his two nicknames, Runt was more common than Jimmy. Perhaps, as he wasn’t particularly small (5-feet-9, 174 pounds) for a ballplayer of his era, it came from the Walsh household, or from Lima’s schoolyards.2 Later, when Walsh played with the Phillies, the nickname helped to distinguish him from another Jimmy Walsh, who played for the neighboring Athletics.

By 1904, as Runt Welsh, the youngster played amateur ball in Lima.3 In 1905, with the Central League’s Dayton Veterans, he made his professional debut. Although he demonstrated a slight “weakness at the bat,” his “speedy playing” at third base suggested a bright future.4

But Walsh “was strong for late hours” and grew “pounds overweight” from “hops and rye.”5 Dayton released him in June 1906. Walsh caught on with Terre Haute, the league’s cellar-dwellers. In 1907 he apparently fell out of professional baseball altogether. He resurfaced in 1908, playing third base in Mississippi with the Cotton States League’s Meridian squad.

Somewhere along the way, Walsh cleaned up his act. In 1909 he returned to the Central League with the South Bend Greens and “developed into the greatest utility player” in the circuit.6 That August 12, as the Greens visited Wheeling to take on the Stogies, Phillies manager Billy Murray scouted the action. Wheeling’s Bill Phillips shut down the South Bend bats, pitching both games of a doubleheader and allowing only one run. Bill McKechnie, then the Stogies’ third baseman, later recalled that “Murray liked the way Walsh struck out, and predicted that some day he would make a real big leaguer.”7 McKechnie’s wit aside, Murray was a respected judge of talent and undoubtedly had Central League contacts. The Phillies drafted Walsh.

By the time Walsh reported to the Phillies’ training camp in 1910, Murray was gone. In his place, new team President Horace Fogel selected catcher Red Dooin to lead the squad. Philadelphia sportswriter William Weart noted of the newcomer’s spring training performance: “Walsh is very quick on his feet for a heavy man and he handles grounders and flies very neatly, while his throwing arm seems to be a dandy. In addition, Walsh has been hitting the ball very hard.”8 Walsh made the team as a utility player and a right-handed bat.

He started the season slowly at the plate and alternated between impressive and poor performances in the field. On May 13, as the visiting Phillies beat the Pirates, 4-0, a Pittsburgh scribe enthused that Walsh “put up a brilliant game at second base [in place of Knabe], and nearly every one of his half dozen assists robbed the Pirates of a hit.”9 But on June 8, in a 7-3 loss to Chicago, he committed four errors at shortstop subbing for Mickey Doolan.10 Walsh soon picked up playing time in the outfield, and in successive games against the visiting Braves in late June, became only the second player in Weart’s memory to blast homers into the National League Park’s left-field bleachers. “Walsh is the best all-round player the Phillies have had in years,” Weart stated of his wide-ranging capabilities.11

Philadelphia finished the 1910 campaign in fourth place, with a 78-75 record. Walsh finished his rookie season with a .248 average (and an OPS+ of 93) in 88 games. He played at least five complete games in six positions: all three outfield spots, third, short, and second.

“Dooin’s Daisies” took on the fiery nature of their skipper. Star outfielder Sherry Magee possessed a notoriously short fuse, and the bruising double-play combination of Knabe and Doolan routinely administered pain to opposing baserunners. President Fogel didn’t calm the waters. His considerable ego created headaches for Dooin, while the moneyed interests that controlled him did little to change the organization’s traditional tightfistedness.

Yet the Phillies at last seemed to shake off their dysfunctional, underachieving ways in 1911. Fred Luderus ably took over first-base duties, while newcomer Dode Paskert starred in center field. Rookie Pete Alexander was an instant pitching sensation. Throughout the season’s first half, Philadelphia competed for the NL lead. Walsh first plugged various infield holes. Then, on June 13, he started in right field for 19 consecutive games. Over this stretch he hit .371.

On July 10 Magee attacked umpire Bill Finneran after being tossed from a game. League President Thomas Lynch suspended Magee for the remainder of the season. Walsh started the next 20 games in left field. During this stretch he hit .271 and robbed both Pittsburgh’s Honus Wagner and Chicago’s Jim Doyle of home runs with leaping catches at the wall.12 The Phillies treaded water over this span, going 11-9. On August 6, after Dooin relieved Walsh of his outfield duties, the Phillies stood 2½ games back in the pennant chase. Over the remainder of the month, despite Lynch commuting Magee’s suspension, Philadelphia slid out of the race as injuries overcame the team.

One of the wounded was Dooin, and catchers shuffled in and out of the lineup. On September 12, as the visiting Dodgers throttled the Phillies, Bunny Madden struggled behind the plate. Walsh, who had caught on the Lima sandlots, offered his services to Dooin. “Walsh’s work in six innings was a revelation, as he handled three pitchers faultlessly, threw hard and accurately to bases, and figured in a double play that showed keen perception and ability to think and set quickly,” reported Philadelphia sportswriter Francis Richter.13 The next day Walsh caught Alexander as he shut out Brooklyn, 2-0.

Walsh needed only a pitching turn to complete his full positional tour. In the season finale against Boston, Dooin summoned him to relieve Bert Hall in the second with the bases full. Hank Gowdy slammed his first pitch over Paskert’s head for a triple. In 2⅔ innings, Walsh yielded eight earned runs and took the loss.14 The Phillies finished the season with a 79-73 record and a distant fourth-place finish. Walsh played 94 games and hit .270 (an OPS+ of 94).

“Manager Dooin,” Richter reported in February 1912, “states that ‘Runt’ Walsh will be given a thorough try-out as catcher during Spring practice and, if successful, assigned permanently to the catcher corps.”15 But Walsh reportedly preferred infield play.16 He started the season at third in place of an injured Hans Lobert.

On April 13, as Philadelphia romped over Boston, Walsh broke his right ankle sliding into third.17 Injuries also took out Magee and catcher Bill Killefer. When Walsh returned on May 27, the team was 11 games behind the eventual pennant-winning Giants.

“Runt devoted every minute of his time to thinking of practical jokes,” Lobert recalled decades later, recounting an incident almost certainly from the 1912 season. Lobert and several other injured Phillies practiced at their home grounds while the team was on a Western road trip. “Working out at the park was the usual string of semi-pros. An awkward looking first baseman attracted our attention. Walsh was just recovering from a broken ankle. Winking at us, Walsh undertook to teach the rookie how to hit. He showed him the wrong way, of course.” This was by having the youngster “hold the bat almost in the middle.” The tale ended poorly for Walsh:

Standing before him, Walsh yelled: “Get your grip higher if you ever want to hit.” The rookie was so flabbergasted at Walsh’s never-ending remarks that the bat slipped out of his hands and flew straight at Walsh. The bat hit Walsh’s old injury with terrific force, re-breaking the ankle.18

As Walsh’s health permitted, Dooin and veteran catcher Pat Moran trained him as a backstop.19 Yet he caught in only five games in 1912. Instead, he spent most of his limited time at second (31 games) and third (12 games). At the plate, he hit .267 (an OPS+ of 84). The Phillies finished in fifth place, with a 73-79 mark.

In 1913 Walsh’s playing time dried up almost completely. The squad enjoyed considerably more health than in previous seasons. Cozy Dolan emerged as Dooin’s primary infield substitute while Beals Becker served as the fourth outfielder. The Phillies sped out to a 38-17 start. Then the team hit a 3-13 stretch. Dooin shook up the lineup at the end of this rough patch and gave Walsh his only two starts (at second) all season. Then, after Dooin put the regulars back, the team recovered from its funk. By that point, however, New York had sprinted to the front of the NL pack. Philadelphia finished the 1913 campaign in a distant second place, with an 88-63 mark. Walsh went 10-for-30 over the entire season.

Seeking an additional catcher of merit, the Phillies obtained Ed Burns from the International League’s Montreal Royals in August. After the season Philadelphia packaged Walsh and three other spare parts (Dan Howley, Doc Imlay, and Doc Miller) together to settle the deal. But as the upstart Federal League recruited that winter, Walsh knew he possessed leverage. Former Phillie and present Royals manager Kitty Bransfield told him that if he did not report, Philadelphia would owe Montreal $5,000.20 While details of Walsh’s salary with the Phillies are elusive, this princely sum was almost certainly much more than his annual pay. He sat tight in Lima.

On January 6, 1914, Knabe signed a contract to manage the Federals’ Baltimore franchise. Immediately he reached out to his ex-teammates. Walsh quickly agreed to a three-year contract at a reported $5,500 per year, plus a $500 signing bonus.21 Doolan soon followed his Phillies friends in jumping to Baltimore.

Walsh whiled away time at Baltimore’s spring-training site in North Carolina with tomfoolery. He artfully strung reporters and locals along with tales that he had survived the Titanic sinking.22 He also conducted one of the most successful “snipe” hunts in baseball history. Walsh and several veteran teammates led a young pitcher into the woods one evening. He laid an open bag on the ground, set a lamp in front of it, and told the rookie, “Now you wait right here and watch them as they run into the bag.” The veterans wandered into the brush with their flashlights, deeper and deeper, calling as they flushed out snipes. “Nawthin’ doing,” the youngster repeatedly yelled back. Walsh and his co-conspirators soon reached their car, and drove off laughing into the night, leaving the rookie to eventually find his way back to the team’s hotel.23 The pitcher, Snipe Conley, kept his nickname throughout his long baseball life.

“It may sound strange,” Knabe told a sportswriter the next day, “but Runt Walsh is too good a ball player to be a regular. I mean he is too good an all-round player. He can play any position with the exception of pitch, and is a splendid hitter. By using him where and when I need him most I can get the best results.”24 But in an April 11 exhibition game, two days before the season began, third baseman Enos Kirkpatrick broke his right ankle sliding into home.25 Walsh at last moved into a major-league lineup to stay.

Baltimore enthusiastically welcomed back major-league baseball, even if the Feds represented a diluted level of quality. The Terrapins rewarded their fans by sprinting out to a fine start; at the end of May they stood 5½ games in front of the pack, with a 22-11 mark. Walsh began the season by marrying fellow Lima native Rose Marie Miller on April 22.26 Married life agreed with him. His bat was the strongest in the lineup, with 8 homers, 23 RBIs, and an OPS of .984 through May. But another right-ankle injury shelved him for nine games.27 After returning, his offensive production tailed off, and he battled another leg injury in September. Walsh finished the 1914 season with 10 homers, 65 RBIs, a .308 average, and an .801 OPS (an OPS+ of 125) in 120 games.

His defensive play at third base was a pleasant surprise. Walsh’s “iron hands” earned particular praise, with a Philadelphia scribe later suggesting that only Milt Stock was his equal among third sackers “when it comes to handling hard-hit balls.”28 When runners did reach base, and negotiated through Knabe and Doolan, they reckoned with Walsh. Years later a Baltimorean recalled that “Runt did many things well but none better than giving the old hip to a base runner rounding third.”29

Baltimore couldn’t sustain its early-season momentum. Yet with workhorses Jack Quinn and George Suggs anchoring the pitching staff, the Terrapins remained in the pennant chase throughout the summer. They eventually finished in third place, 7½ games out, with an 84-70 record. That offseason, Baltimore added Chief Bender to the staff and Yip Owens to the catching ranks but otherwise stood pat.

The Terrapins’ 1915 season started unimpressively, then progressively worsened. By July 8, they occupied the cellar. From that point, the team won only 20 of its remaining 82 games to finish with a dismal 47-107 mark. Yet Walsh’s competitive spirit did not dim. On July 17 at St. Louis, the Terrapins were tied with the Terriers, 3-3, in the top of the eighth. With two outs and the bases loaded, Walsh stood on third. He asked Doc Crandall, the St. Louis pitcher, to see the ball. Crandall innocently lobbed the ball to Walsh. The Terrier third baseman, Tex Wisterzil, remained focused upon the batter. Walsh let the ball bounce in front of him, broke for home, and before Wisterzil came to his wits, crossed the plate with the go-ahead run. St. Louis, however, scored four runs in the bottom of the inning and went on to win, 7-4.30

On August 14 Walsh yet again injured his ankle, kicking third base in frustration when a call went against him.31 Baltimore soon began releasing under-performers and selling players of value. Walsh, who was hitting .302 (an OPS+ of 120), with 9 homers and 60 RBIs (both team highs), was sold to St. Louis.

On the strength of three starters — Crandall, Dave Davenport, and Eddie Plank — the Terriers contended for the pennant all season. But their current third baseman, Art Kores, sustained a hand injury on August 27. As soon as Walsh arrived, St. Louis manager Fielder Jones put him into the starting lineup, on September 1 versus Pittsburgh. But in the second inning, one of Clint Rogge’s pitches hit Walsh in the head.32

Walsh missed only the next day’s start. Yet his gimpy leg and any lingering effects of Rogge’s pitch hindered his performance in the field and at the plate. After a week, Jones placed Walsh on the bench, and handed third-base duties to the returning Kores. St. Louis finished a close second behind Chicago.

Baseball peace came in December 1915. Terriers owner Phil Ball, intent on remaining a major-league magnate, was promised such an opportunity in the peace talks, and soon purchased a controlling interest in the St. Louis Browns. The peace treaty permitted Ball to take his Terriers personnel into the Browns’ orbit. Ball pushed aside Branch Rickey as the Browns manager and replaced him with Fielder Jones. Then he gave Jones free rein to decide which players from the Terriers-Browns merger to retain.33

“He’s a good man with the bat, a wise base runner and the slickest signal-stealer I ever knew,” Jones said of Walsh in February 1916.34 But Walsh was aging, increasingly injury-prone, with his fielding not quite up to the standards of the now-consolidated major leagues. A year of salary also remained in his hefty Federal League contract. Walsh later claimed that, as he attempted to rejoin the majors, the Phillies offered him unsatisfactory salary terms.35 In St. Louis, Jones passed Walsh over for a spring-training invitation, and it fell upon the demoted Rickey to unload him. Undoubtedly with the Browns taking on some salary obligations, Rickey sold Walsh to the Southern Association’s Memphis Chickasaws.36

Walsh held down the Chickasaws hot corner and batted .272 with 32 extra-base hits. In March 1917 he was sold to Rochester, a squad managed by his old friend Mickey Doolan. Walsh found a Bethlehem Steel League salary more satisfactory. For the next two seasons he played for the independent league’s Sparrows Point squad, just outside Baltimore.

In 1919 he came back to Organized Baseball, recruited by another former mate, Red Dooin, to join the Reading team he managed. Doolan soon joined the reunion. But the hapless squad fell into the International League cellar. Reading’s owners pressured Dooin to release Doolan and Walsh in early August. Dooin refused and quit. His friends were released.37 For Runt Walsh, it marked the end of his professional baseball career.

After an initial business foray in Jersey City, Walsh returned to Baltimore by the mid-1920s. He went into the restaurant business, and commonly took part in local old-timer’s games. At some juncture he remarried, for the 1940 census finds him wed to Colette.38 No children are listed in their household, nor is it apparent if his earlier marriage produced any offspring. On January 21, 1947, Walsh died in Baltimore. Colette survived him. He rests in Baltimore’s New Cathedral Cemetery.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Walsh’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, and the following sites: ancestry.com, genealogybank.com, and newspapers.com.

Notes

1 Per Baseball-Reference’s play index, Spider Clark was the first to accomplish this feat in 1890 with the Players League’s Buffalo Bisons. Sport McAllister repeated the feat nine years later with the infamous Cleveland Spiders. Altogether, through 2017, 12 players have played each position in a season.

2 As is the case with most ballplayers of this era, his height is a matter of guesswork. In his Hall of Fame questionnaire, completed by William Walsh (likely his brother), he is listed at 5-feet-7. In his World War II draft registration, Runt himself lists his height at 5-feet-4. But a 1930 photograph of him standing alongside Buck Herzog and Steve Brodie at an old-timer’s game shows him as the same height as these two, both listed at 5-feet-11. See “Baseball Stars of Other Years in Action at Oriole Park,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1930.

3 Lima News, April 23, 1904.

4 “Veterans Open Season at Wheeling,” Dayton Herald, April 26, 1906.

5 “‘Runt’ Walsh is Behaving,” Dayton Herald, June 3, 1909; “Walsh, Central Star, Slugging for Phillies,” Indianapolis Star, June 27, 1910; “‘Aqua Pura’ Kid Has a Real Rival in ‘Runt’ Walsh,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 26, 1911.

6 “‘Runt’ Walsh,” Lima Morning News, September 19, 1909.

7 William Peet, “Treat ’Em Rough,” Pittsburgh Post, January 13, 1925. While McKechnie’s tale is a bit tall, South Bend did play a doubleheader in Wheeling that day. See Indianapolis Star, August 13, 1909. The Phillies were in Pittsburgh. Murray did occasionally scout that season.

8 William G. Weart, “Phillies in Luck,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1910: 2.

9 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, May 14, 1910.

10 His adopted surname was variously spelled “Doolan” and “Doolin” throughout his 71 years. See his biography at sabr.org/bioproj/person/b2f31749.

11 William G. Weart, “Too Much Pitcher,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1910: 2.

12 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Luderus’ Smashes Beat Pirates, 2-1,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 16, 1911; I.E. Sanborn, “Schulte’s Swats Defeat Phillies,” Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1911.

13 Francis C. Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, September 23, 1911: 7.

14 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Phils Close Season with Double Defeat,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1911.

15 Francis C. Richter, “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, February 24, 1912: 7.

16 “Three Leagues,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 10, 1911; “Walsh Refused Bonus,” Washington Evening Star, May 7, 1912.

17 “Walsh Is Latest Victim of Jinx,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 14, 1912.

18 James C. Isaminger, “Old Sport,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 13, 1940.

19 “‘Runt’ Walsh for a Catcher,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1912.

20 Walsh’s affidavit from the 1915 The Federal League of Baseball Clubs vs. The National League, et al. available via sabr.org/research/1915-Federal-League-case-files. See also “Players for the Royals,” Montreal Gazette, December 11, 1913.

21 “Walsh Signs with Federals of Baltimore,” Lima News, February 21, 1914. This article reports the contract as a five-year one but elsewhere (including Walsh’s affidavit) it is referred to as a three-year deal.

22 “‘Runt’ Walsh Tells About Trip Abroad to His Baltimore Friends,” Lima Times-Democrat, June 16, 1914.

23 C. Starr Matthews, “Terrapins Hunt for Wee Snipes,” Baltimore Sun, April 3, 1914.

24 C. Starr Matthews, “Kirkpatrick to Play Third Base,” Baltimore Sun, April 4, 1914.

25 “Enos Kirkpatrick Breaks Ankle,” Baltimore Sun, April 12, 1914.

26 “Runt Walsh a Groom,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1914.

27 “Terrapin Players on Hospital List,” Baltimore Sun, June 1, 1914.

28 C. Starr Matthews, “Packard Blanks Terps,” Baltimore Sun, May 1, 1915; “Gardner, of Boston, Outranks Stock in Poise and Experience,” Philadelphia Evening Ledger, October 4, 1915.

29 “Old-Timers to Strut in Elks’ Day Saturday,” Baltimore Sun, August 11, 1930.

30 “Brand New Trick Baffles Crandall but Terriers Win,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 18, 1915.

31 C. Starr Matthews, “10,000 See Terps Split,” Baltimore Sun, August 15, 1915.

32 “Rebs Want Revenge on Terriers,” Pittsburgh Press, September 2, 1915.

33 For this background, see Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009): 284-286, 305-306.

34 W.J. O’Connor, “Jones Will Take 29 Men South; To Drop 7 of These,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 25, 1916.

35 “Players on the Stand,” Baltimore Sun, March 28, 1919.

36 For insights into this player glut, and salary challenges, see “Salesman Instead of Scout His Need,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1916: 2.

37 “Dooin Quits as Manager of Reading,” Reading Times, August 4, 1919; “Karpe’s Comment on Sport Topics,” Buffalo Evening News, August 6, 1919.

38 In the 1930 Baltimore city directory, Rose is listed with Walsh. (But the 1930 US census lists Walsh alone in his household.) An Ancestry.com family tree suggests she died between 1925 and 1950, but Maryland death records provide no clues. Colette, meanwhile, is listed as a Maryland native in the 1940 census.

Full Name

Michael Timothy Walsh

Born

March 25, 1886 at Lima, OH (USA)

Died

January 21, 1947 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.