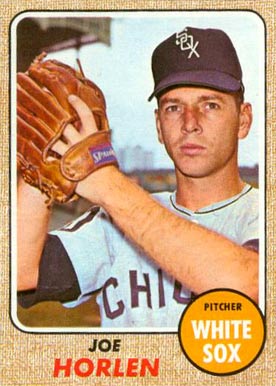

Joe Horlen

A name can sometimes be confusing. Four years into his major-league career, Joel Edward Horlen said that though the news media and fans knew him by his proper name, Joel, “All my friends call me Joe and that’s what I go by. When I got into baseball, it became Joel somehow. I guess because that’s how I sign my contract.”1

A name can sometimes be confusing. Four years into his major-league career, Joel Edward Horlen said that though the news media and fans knew him by his proper name, Joel, “All my friends call me Joe and that’s what I go by. When I got into baseball, it became Joel somehow. I guess because that’s how I sign my contract.”1

Often overlooked as one of the best pitchers of the 1960s, Joe Horlen led all American League pitchers with a 2.32 ERA over a five-year period (1964-68) as the right-handed ace of the Chicago White Sox. (Chicago led the AL in team ERA for three of those five seasons.) After pitching for the notoriously weak-hitting South Siders for his first 11 years, Horlen concluded his career as a reliever and spot starter for the world champion Oakland Athletics in 1972. With a career record of 116-117, Horlen could lay claim as one the best pitchers with a losing record in major-league history.

Born on August 14, 1937, in San Antonio, Texas, to Kermit and Geneva Horlen, Joel Edward Horlen wanted to be a major-league pitcher from the time he was child. His father, a former semipro catcher, played in a Sunday beer league where Joe, as his parents called him, and his younger brother, Edward, were introduced to the game. Kermit, an executive at an insurance company, played an active role in Joe’s development as a pitcher and coached him from the time he started playing organized baseball through his high-school days. “My dad [built] a pitching mound in the backyard and [hung] a tire on a rope by the shed that we had,” Horlen said. “My mother gave us an old rug and we put it over the tire and just threw to it all day long.”2

By the time he was about 10 years old, Joe began playing for his father on a YMCA team and in 1952 was on the first-ever PONY League national championship team. At Burbank High School in San Antonio, he earned letters in basketball, football, and golf, but his school did not field a baseball team. A small, quick, and versatile athlete, Joe played shortstop on his American Legion team led by future major-league pitcher Gary Bell and pitched occasionally, and also honed his pitching skills in Sunday beer leagues.

After graduating from high school in 1956, Horlen was picked to play in the national Hearst Baseball Sandlot Classic.3 The Cleveland Indians sought to sign him, but Horlen was recruited by baseball coach Toby Greene of Oklahoma State University and enrolled there, intending to play baseball and study geology. In 1959, as a junior, he posted a 9-1 record, including three victories in the NCAA tournament and led the Cowboys to the championship, upsetting the University of Arizona. “Every major league scout in the Southwest was on his trail,” The Sporting News reported.4 White Sox scout Ted Lyons had been following Horlen for two years by the time the Cowboys made it to the College World Series in Omaha, and Chicago sent Jack Sheehan, the team’s farm director, to scout the tournament. “Jack talked with me and all he asked was that before I signed with anyone that I’d promise that he’d be the last person I talked with,” Horlen said.5 In the wake of the Cowboys’ victory celebration, Horlen contacted Sheehan at 2:30 A.M. and accepted the team’s contract offer, which included a reported $30,000 bonus.6

Horlen was hit in the pitching arm by a line drive in his first game for the Lincoln (Nebraska) Chiefs of the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League, but nevertheless started four times, relieved once, and pitched 41 innings in a 13-day span to begin his professional career. “My arm wasn’t sore or anything,” he said of the initial heavy workload that led to a disappointing 1-9 record, “but it was just dead for the rest of the year!”7 With a 5.64 ERA in 91 innings (13 starts), Horlen was sent to the Florida Instructional League after the season. Promoted to the Charleston (South Carolina) White Sox in the Class A South Atlantic League to start the 1960 season, he was forced out of the starting rotation by a sore arm. After 26 appearances (12 starts) and a 2.92 ERA in 120 innings, Horlen’s season was cut short when the White Sox medical staff determined that he had a pinched nerve in the arm.

After playing again in the Instructional League in 1960, Horlen was added to the White Sox’ 40-man roster and went to his first big-league spring training in 1961. A coachable, hard-working, and intense pitcher, Horlen was assigned to the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League. He credited managers Bob Kuzava at Charleston and Bill Norman in San Diego with helping him learn to set up hitters and develop into a bona-fide major leaguer. At San Diego Horlen posted a 12-9 record on a losing ballclub. Norman praised Horlen’s ambition and considered him the best pitching prospect he had seen since Mike Garcia in the late 1940s. With a 2.51 ERA (second in the league) in 197 innings, Horlen attributed his new-found stamina to his close work with Herb Score, who was attempting a comeback with the Padres.

A September call-up, Horlen joined the White Sox in Minnesota and was slated to start against the Twins on September 5, but was surprised when he was called to relieve Cal McLish to start the fourth inning on the 4th. “I was sitting in the bullpen wearing my warm-up jacket because I was a little embarrassed (his uniform with his number and name on the back had not arrived) and the guys were giving it to me,” said Horlen. “Then during the middle of the game the phone rings and Al Lopez said to get me up and ready. [When] I’m ready to throw my first pitch in the majors, Twins manager Sam Mele called time and went out to talk with the home-plate umpire … and shrugs his shoulders like ‘who the heck is that guy?’ Everyone got a good laugh out of it including myself and it might have helped me since it relieved the tension.”8 Horlen pitched four scoreless innings, surrendering just two hits, and earned the victory in his major-league debut. But he was hit hard in four subsequent starts, and finished with a 1-3 record and 6.62 ERA.

Manager Al Lopez and pitching coach Ray Berres were convinced that Horlen would be successful as soon as he learned to control his “big roundhouse curve,” which came in head-high and dropped to the batter’s knees.9 Playing after the season for the Mayaguez Indians in the Puerto Rican Winter League, Horlen began throwing his curveball faster to lessen the break. With his hard curve, a fastball with good movement, and a sinker, Horlen emerged as one of the league’s best pitchers. Pitching an unfathomable 401 innings in a 12-month period (186 with Mayaguez, 197 with San Diego and 18 with the White Sox), Horlen was tabbed the “likely rookie pitcher of the year” for the 1962 season by The Sporting News.10

Named to the White Sox’ starting rotation in 1962, Horlen opened the season by pitching an impressive complete-game five-hitter against the California Angels on April 12, allowing just one run. The game foreshadowed his career with Chicago in the 1960s: The light-hitting White Sox were shut out and Horlen’s reputation as a “tough-luck loser” was in the making. In his next start he pitched his best game of the season, blanking the Twins on six hits. The 24-year-old Horlen was benefiting from working with coach Berres, who taught him how to set up hitters, keep his pitches low in the strike zone, and let the batters get themselves out. “Ray was an absolute stickler for mechanics,” Horlen said. “He’d watch you when you were throwing on the sidelines and he’d keep reminding you about little things … things that made a big difference, like your arm swing, staying on top of the ball and the position of your body.”11 Not an overpowering pitcher, Horlen learned to approach pitching and batters cerebrally; no longer concerned about hitting the corners, he let his natural abilities come to the surface. Finishing May with two consecutive complete games that pushed his record to 5-2, Horlen seemed to fulfill preseason projections, but after enduring a rough June (19 earned runs in 18⅓ innings), he tore a muscle in his pitching shoulder and missed ten weeks. Returning in September to win two of three decisions, Horlen finished the season with a 7-6 record and 4.89 ERA. In the offseason he worked for the White Sox’ ticket office.

Now tabbed the “best young pitcher” in baseball, Horlen began the 1963 season with a new-found sense of confidence.12 After winning his first start, against the Angels, Horlen was plagued by wildness in his next four starts and lost his spot in the rotation after a disastrous outing against the Angels on May 12 in which he got just one out in the first inning and gave up three hits before Lopez yanked him. Struggling with his command out of the bullpen and as an occasional spot starter, Horlen finally was optioned to the Indianapolis Indians in the American Association in early July to work on his curveball and regain his confidence. Overpowering the competition with three wins and a 1.74 ERA, he was recalled and defeated the Detroit Tigers on July 25 in his first start back. Four days later, pitching against the Senators in Washington, he had a no-hitter and a precarious 1-0 lead going into the ninth inning. After losing the no-hitter on a one-out single by Chuck Hinton, Horlen lost the game when Don Lock crushed a two-out walk-off home run. Horlen concluded the season with four consecutive victories, posting an 11-7 record and 3.27 ERA on a staff considered the best in the league.

After leading San Juan to the Puerto Rican Winter League title in 1963-64, Horlen was a contract holdout and paid his own expenses to spring training before finally signing a contract at the end of camp. In his season debut he gave up four runs in three innings in a 4-1 loss to the Boston Red Sox. Losing his patience with his young hurler, Lopez sent him to the bullpen, where he saw action in just four games in the next five weeks. After a spot start on May 24 against the Senators in which Horlen gave up two earned runs in five innings in a 3-0 loss, Lopez put him back into the rotation and Horlen pitched well but with little luck. Though he posted 1.84 ERA in 44 innings in June, he won just two of five decisions as the White Sox provided him a total of seven runs in his six starts in the month. Then he turned things around, concluding the first half of the season with three consecutive complete-game victories. He struck out a career-high ten batters against the Senators on July 1 and hurled a four-hit shutout against the Indians on July 5. With his “souped-up curve,” the slender right-hander was the hottest pitcher in baseball.13 “I like to work hitters in and out, up and down,” said Horlen, “but never have I been able to put the ball so well where I want.”14

Despite Horlen’s third consecutive month with a sub-2.00 ERA in July, critics pointed to his one complete game in the prior eight starts as proof that he “tires in late innings” and lacked stamina.15 Unknown to most at the time, Horlen suffered throughout the month from a recurrence of pain in his right shoulder that required cortisone shots. From a career perspective and in context of pitching in the 1960s Horlen did not pitch many complete games (59 in 290 starts) and reached double figures only once (13 in 1967). However, managers Lopez and Eddie Stanky, for whom Horlen pitched from 1961 through 1968, had reputations for being “quick hooks” and were also blessed with deep and extremely effective and efficient bullpens with knuckleballers Hoyt Wilhelm, Eddie Fisher, and Wilbur Wood, as well as Bob Locker. A nervous type on and off the mound, Horlen credited veteran Wilhelm with helping him to learn to relax while pitching and to throw naturally instead of leading his pitches or aiming at the corners.

Pitching his best in September when the White Sox needed it most, Horlen posted a 1.07 ERA with four complete games and won three of four decisions. Duplicating his career high of ten strikeouts in a victory over the Indians on September 5, Horlen gave the White Sox a surprising one-game lead over the New York Yankees, whom they battled the entire season in an exciting pennant race. The White Sox relied on their “Big Three” pitching stars – 20-game winner Gary Peters, 19-game winner Juan Pizarro, and Horlen. Pitching on three days’ rest for almost the entire month of September, Horlen tossed a complete-game victory against the Athletics on September 27 and a two-hit shutout over the A’s on October 3 to give the White Sox their eighth consecutive victory, but the Sox could not overtake the Yankees, who went 24-9 down the stretch to win the pennant. “We thought we were going to win [the pennant]” Horlen said.16 Provided just nine runs of support in his nine losses, Horlen won 13 games, was second in the AL with a career-low 1.88 ERA, and limited hitters to a .190 batting average by surrendering a league-low 6.1 hits per nine innings.

With a crew-cut hairstyle and brown eyes, Horlen lived in the offseason in his hometown of San Antonio with his wife, Catherine, whom people called Kitty, and raised a daughter and a son. Quiet and soft-spoken, he worked for an insurance company and had the reputation of investing wisely and eschewing grand expenses. Balking at Chicago’s 1965 contract offer for “less than $14,000,” Horlen was a holdout for the second year in a row, finally reporting in mid-March.17

Horlen pitched consistently all season and led the team with 34 starts, a 2.88 ERA, 219 innings pitched, and four shutouts, yet finished with just a .500 record (13-13) on a team that won 95 games and finished in second place behind the surprising Twins. (It was Al Lopez’s tenth second-place finish.) The White Sox scored two runs or fewer in eight of Horlen’s losses and four runs or more just twice.

Accepting his contract the day before 1966 spring training opened, Horlen was greeted by new manager Eddie Stanky who had replaced the easygoing player’s manager Lopez. Stanky, known as the the Brat in his playing days, pushed his players and instituted an aggressive, hit-and-run-style game uncommon in the 1960s. On a weak-hitting team (last in the AL with a .231 average), the small and quick Horlen was used a pinch runner 27 times. “I learned more about baseball from Eddie than any other manager I ever played for,” he said. “He was tough, some guys just didn’t get along with him. Eddie would walk up and down the dugout during a game and he’d often stop by a guy and ask him, ‘What’s the count?’ If you didn’t know it you’d be fined $25.”18

Beginning with a complete-game 2-1 loss to the Angels on April 14, Horlen lost six of his first seven decisions despite owning a stellar 2.64 ERA at the end of May for the 19-21 Sox. In June and July he won six of ten decisions, and tossed his first shutout of the season on July 2, against Boston. He suffered from another bout of shoulder pain in August and failed to make it out of the second inning in two of four starts. Demoted to the bullpen, Horlen made six appearances, the last of which marked an improbable reversal of his season. In relief of Gary Peters on September 9, Horlen held the Senators to three hits over six innings in a scoreless game before giving way to Hoyt Wilhelm in the tenth inning. That earned Horlen his first start in three weeks, and he hurled a three-hit shutout against the first-place (and eventual World Series champion) Baltimore Orioles on September 16. Then he blanked the Yankees for seven innings to earn his tenth and final victory of the season on September 22, and threw eight more scoreless innings in a no-decision against Boston. Horlen’s scoreless streak reached 32 innings before the Yankees ended it and dealt him in his last loss of the season on October 1. Finishing with an 83-79 record, the White Sox set an AL record for the lowest team ERA (2.68). Gary Peters led the league with a 1.98 ERA, and Horlen posted a 2.43 ERA in 211 innings. Provided three runs or fewer in 11 of his losses, Horlen saw his record fell to 10-13, his first losing season as a starter.

Confident in his abilities and in the best shape of his life after undergoing a rigorous offseason exercise regimen and officiating at local basketball games, the 29-year old Horlen braced for a career year in 1967. “If you can stay loose and relaxed,” he said, “you won’t be pressing and you’ll retain your rhythm. If you have your rhythm, you’ll have good motion. That means you’ll have good control.”19 Horlen had a peculiar way of staying loose: He chewed a wad of tissue. Explaining that got sick when he tried to chew tobacco and felt bloated when he chewed gum, Horlen began chewing tissue because “it relaxes me.”20

Dogged by criticisms that he lost concentration in games, Horlen got off to the best start in his career in 1967.21 With two different fastballs (a sinker and one that broke away from right handers) and a hard curve, Horlen tossed two complete-game victories over the Senators in a week, the latter being his fourth and final career two-hitter, a 1-0 shutout in front of just over 4,100 Washington fans on April 22. Regularly accused of throwing a spitball, Horlen denied the charge, but years later admitted, “I threw about 20 spitballs in one game but it was just to see if I could get away with it.”22 With a team-leading ten wins for the first-place White Sox in early July, Horlen was named to the American League All-Star team for the first (and only) time, but did not pitch in the game.

Horlen won four of five decisions to begin the second half of the season, and his 3-1 victory over the Orioles on August 18 pushed his record to 14-3 and kept the White Sox in an exciting four-team pennant race with the Twins, Tigers, and Red Sox. After losing his last three starts in August, Horlen ditched his slider (which he thought negatively affected his fastball because of its delivery), threw his curveball one out of three pitches, and relied even more on his fastball. He pitched a no-hitter against the Tigers on September 10. Horlen’s only blemishes were two hit batters. Then, pitching on short rest, he tossed consecutive shutouts over the Angels on September 19 and the Indians (a three-hitter) on September 23, his 19th victory of the season. In third place one game behind the Twins with five games to go, the White Sox lost those five games to two second-division teams, the Kansas City Athletics and the Senators, and finished in fourth place at 89-73. Horlen was the loser when the A’s shut out the White Sox 4-0 on September 27, effectively ending the team’s pennant hopes, and then failed in his bid to win his 20th game in the final, meaningless match of the season. In his best big-league season, Horlen posted career highs with 19 wins, 258 innings pitched, 13 complete games, and a league-leading six shutouts and 2.06 ERA. Holding opponents to a .203 batting average, Horlen walked just 58 batters and led the AL with a 0.953 WHIP.23 The White Sox staff set a major-league post-Deadball-era record with a 2.45 ERA.

Coming off an exciting and emotionally draining season in 1967, the White Sox lost their first ten games of 1968 on their way to a tumultuous 67-95 season during which Stanky and his replacement Les Moss were fired and 60-year old Al Lopez was brought back for the last seven weeks of the season. Horlen pitched inconsistently and lost his first five starts. Bothered by calcium deposits on his shoulder all season, he struggled to pitch deep into games and had only four complete games. One of those came on May 17 when he pitched ten innings in a four-hit, 1-0 shutout of the Oakland A’s. He held the Orioles scoreless for seven innings and the Yankees scoreless for 8⅓ in his next two starts, both no-decisions, and ran his scoreless streak to a career-best 37 consecutive innings before giving up a run in a complete-game 3-1 victory over the Orioles on May 29. With Gary Peters suffering an off-year and Tommy John injured, Horlen was the workhorse of the staff, finishing with a 2.37 ERA in 223⅔ innings, but a 12-14 record. The White Sox scored only 15 runs in his losses.

After an offseason procedure to remove calcium deposits in his shoulder and heal “atrophied areas of his deltoid muscle,” Horlen began spring training in 1969 in good health.24 “I didn’t have any arm strength,” he said of the previous season, and had “active pain every time I pitched.”25 The White Sox finished with 94 losses (only four less than the expansion Seattle Pilots). Horlen started 35 games for the third consecutive season and paced the team with 13 wins, but lost a career-high 16, and posted a 3.78 ERA in 235⅔ innings, the sixth consecutive (and final time) he exceeded 200 innings in a season.

A pilot as well as a ballplayer, Horlen flew his own plane to spring training in Sarasota in 1970.26 After losing his season debut, Horlen defeated the Angels for his 100th career victory on April 14. He was 5-2 on May 15, but then entered the most frustrating period in his career. Pitching for the worst team in White Sox history (loser of 106 games), Horlen won only one of his next 15 decisions. His season appeared to be over when he discovered that he had torn cartilage in his right knee after a start on July 28.27 But Horlen showed “tremendous determination” by coming back five weeks later to make four appearances in September, and finished the season at 6-16 with a career-worst 4.86 ERA.28

After venting his frustration at team officials who questioned his work ethic and commitment to baseball during the disastrous 1970 season, Horlen felt more comfortable with new White Sox skipper Chuck Tanner and pitching coach Johnny Sain. As fate would have it, Horlen tore cartilage in his left knee sliding into second base in the last preseason game. “I was going to do a ‘pop-up’ slide,” he said, and “when I threw my left leg back as I hit the dirt I heard a loud pop in my knee. The leg was locked into a 90-degree angle. I just couldn’t bend it back.”29 After knee surgery on April 5, Horlen made it back on the field in just 29 days when he pitched two innings of scoreless relief against Boston. Lauded by Tanner for his “true grit,” Horlen split his time between starting and relieving and posted an 8-9 record with a 4.26 ERA for the surprising White Sox, who finished 79-83.30

Horlen was the White Sox’ union representative in 1971 and 1972, and argued in favor of the players’ strike in 1972. He clashed with White Sox general manager Stu Holcomb, and was released at the end of spring training, on April 2, the day after players voted for the strike. At a meeting of the Players Association as the team representative (the players had not had time to elect a new one), Horlen was told that Oakland had attempted to acquire him in an offseason trade.31 He called A’s owner Charlie Finley. “He asked me about being waived and how my legs were,” Horlen said. “I told him that they were fine. He said, ‘I’ve been keeping up with the strike. It’s not going to last more than ten days. After five days we’re going to send you a plane ticket to come to Oakland.’ ”32

Pitching primarily in long relief, Horlen logged 84 innings and notched a 3.00 ERA for the world champion A’s. He appeared once in Oakland’s seven-game World Series victory over the Cincinnati Reds, relieving Dave Hamilton in the seventh inning Game Six (an 8-1 Oakland loss) and giving up two hits, two walks, and a wild pitch in an inning and a third. It was the last time Horlen pitched in the major leagues. Released in the offseason, he announced his retirement. He finished with a 116-117 record and a 3.11 ERA in 12 seasons.

Horlen began working as a building contractor in San Antonio, but was persuaded to join the San Antonio Brewers, the Double-A affiliate of the Cleveland Indians, in midsummer as a pitcher and mentor to the team’s young staff.33 He won six games and lost just one, then worked as a roving minor-league pitching instructor for the Indians for two years before returning to San Antonio, where he owned and operated construction and roofing companies. After a divorce, Horlen married Lois Eisenstein in 1981 and converted to Judaism. He helped start a golf program at the University of Texas at San Antonio.34 Persuaded to return to baseball in 1987, Horlen served as a minor-league pitching coach and roving pitching instructor over the next 14 years in the farm systems of the New York Mets, Kansas City Royals, San Francisco Giants, and San Diego Padres.

“I had only one goal and that was that I never wanted to embarrass myself out there on the mound,” said “Hard Luck Horlen” as he was often known during his years with the White Sox in the 1960s. “I had pride, that’s the way I was my whole career. I couldn’t control how good or bad the team was, I could only control myself.”35 Still a resident of his hometown in 2013, Horlen followed baseball closely and was involved with special events and anniversaries of the White Sox.

Horlen died at the age of 84 on April 11, 2022.

Last revised: April 18, 2022

This article appeared in “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions: The Oakland Athletics: 1972-74″ (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene.

Sources

Joe Horlen player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet.com

The Sporting News

Notes

1The Sporting News, February 13, 1965, 5.

2 Mark Liptak, “Flashing back . . . with Joel Horlen,” White Sox Interactive.com. http://www.whitesoxinteractive.com/rwas/index.php?id=2755&category=11

3 The Sporting News, August 8, 1956, 38.

4 The Sporting News, March 14, 1962, 8.

5 Liptak.

6 The Sporting News, March 14, 1962, 8.

7 Liptak.

8 Liptak.

9 Liptak.

10 The Sporting News, April 11, 1962, 46.

11 Liptak.

12 The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 14.

13 United Press International, July 22, 1964. In Horlen’s Hall of Fame file.

14 Ibid.

15 The Sporting News, September 26, 1964, 5.

16 Liptak.

17 The Sporting News, February 13, 1965, 5.

18 Liptak.

19 The Sporting News, August 13, 1966, 13.

20 The Sporting News, June 17, 1967, 27.

21 The Sporting News, May 6, 1967, 7.

22 Gary Herron, “Horlen was a classic, good-pitch/no-hit hurler,” Sports Collectors Digest, March 17, 1995, 139.

23 WHIP refers to the total number of walks and hits given up dived by innings. A WHIP of 1.0 means that the pitcher surrendered an average of nine hits and walks per nine innings.

24 The Sporting News, February 8, 1969, 42.

25 Ibid.

26 The Sporting News, April 11, 1970, 58.

27 The Sporting News, August 8, 1970, 12, and August 15, 1970, 15.

28 The Sporting News, December 5, 1970, 51.

29 Liptak.

30 The Sporting News, June 12, 1971.

31 The Sporting News, April 22, 1972, 14.

32 Liptak.

33 “Horlen Signs with Brewers” [no publication; 1972]. In Horlen’s Hall of Fame file.

34 Herron, 139.

35 Liptak.

Full Name

Joel Edward Horlen

Born

August 14, 1937 at San Antonio, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.