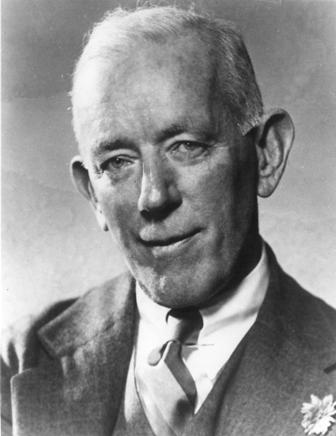

John F. Kieran

John Kieran stands among the legends of baseball writing with his J.G. Taylor Spink Award and place of honor in the Scribes and Mikemen exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame.1 But baseball and even the broader realm of writing sports per se occupied only a part of Kieran’s career as a newspaperman, and he achieved at least equal acclaim as a wide-ranging columnist, popular media personality, naturalist, and award-winning author who was described as “a walking encyclopedia” in his New York Times obituary.

John Kieran stands among the legends of baseball writing with his J.G. Taylor Spink Award and place of honor in the Scribes and Mikemen exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame.1 But baseball and even the broader realm of writing sports per se occupied only a part of Kieran’s career as a newspaperman, and he achieved at least equal acclaim as a wide-ranging columnist, popular media personality, naturalist, and award-winning author who was described as “a walking encyclopedia” in his New York Times obituary.

Kieran started in 1915 as a golf writer with the Times, and then moved to the New York Tribune baseball beat under Grantland Rice in 1922. After a brief stint with the New York American in the Hearst chain2, he returned to the Times, lured by the prospect of crafting that paper’s first bylined column of any kind. “Sports of the Times” debuted January 1, 1927, and Kieran wrote it until late 1941, when he left the Times and sports for a general interest column in the New York Sun.3 By that time Kieran’s erudition and a recommendation from Herald Tribune4 columnist Franklin P. Adams had landed him a spot on NBC Radio’s “Information Please” quiz show panel, where he began providing extemporaneous sports and other expertise in 1938. Kieran left newspaper work in 1944, and when “Information Please” ended its radio run, he took his unique skills to the new medium of television. He worked in editing while continuing to write about the outdoors before retiring in 1952 to coastal Massachusetts, where his nature writing flourished.

John Francis Kieran was born August 2, 1892, in the semi-rural Kingsbridge section of the West Bronx, New York City, to James M. and Kate Donohue Kieran, both Irish-Americans. James Kieran was a New York public school principal who became a professor at and ultimately president of Hunter College, the prestigious women’s school. Kieran’s mother also taught school prior to marriage. The Kieran home was book-and-learning oriented, and the seven Kieran children were sometimes referred to as “the seven smart Kierans”–a brother, James, wrote for the Times and helped establish the American Newspaper Guild; a sister, Helen Kieran Reilly, wrote mystery novels; and another brother, Leo, also wrote for the Times. Always waggish, John Kieran liked to describe his family as “poor but Irish” and said that his mother “wrote poetry but otherwise showed no mark of derangement.”

“Really a country boy all the time,” as Kieran characterized himself, he recalled growing up in a neighborhood of unpaved streets, apple orchards, backyard vegetable gardens, and horse-drawn buggies and sleighs. His family kept rabbits and pigeons, while he and his siblings scouted the woods, played baseball, swam in the summers and skated and bobsledded in the winters. The family owned a small farm in Dutchess County, which Kieran described in Not Under Oath as a family vacation playground. “I dreaded the return to the city in autumn. I roamed the fields and woods all day and at night I slept in a tent on a knoll above the farmhouse. In short, I wanted to live there if possible.”

Kieran attended P. S.103 in Harlem, graduated from Townsend Harris High School, and enrolled in City College of New York before a transfer to Fordham University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in 1912. He played shortstop at both City College and Fordham and after college played as much golf and tennis as his schedule allowed. Hiking was a lifetime avocation.

Disdaining further education and making good at least temporarily on his desire to live on the Dutchess County property, Kieran convinced his father to back him financially in a poultry business on the farmstead. He also picked, packed, and shipped barrels of apples, and, to supplement income and “help with the bills for chicken feed,” taught in a one-room Dutchess County school that served the local farm community. But, “I did not prosper. I had a hound and a horse and a gun and I loved the life on the farm, but I couldn’t make a living there. Even so, a year on the farm had left a deep mark on me. It had quickened my youthful love of the outdoors into a growing interest in natural history.”

Back in New York, Kieran shunned employment that would have confined him to an office and took work as a construction company handyman. From immigrant laborers he acquired a conversational knowledge of Italian. He also used the job to learn the rudiments of civil engineering and stuffed his pockets with books on poetry, plant life, astronomy, and varied other subjects for subway rides when work took him across the city: “As long as Kieran had a book handy there was no such thing as an idle moment,” William Curran notes in Kieran’s entry in Gale’s Dictionary of Literary Biography.

Despite the opportunities for subway study, Kieran eventually found the long, crowded rides stifling. In Not Under Oath he recalled, “After giving the matter a little thought, I decided to become a newspaperman. Like everybody else, I believed that I could write if I had the chance.” It was 1915 and the chance came through a family friend, Frederick T. Birchall, assistant managing editor of the New York Times. Birchall knew Kieran’s familiarity with athletics and assigned him to the sports department, where he spun his wheels for a few weeks, then turned acquaintance with a local country club golf professional into a story about the club. That convinced the Times city editor that the paper needed a regular golf writer and that Kieran should have the beat. “A most pleasant assignment it was,” Kieran recalled, and through it he met another young golf writer who became a lifelong friend, Grantland Rice.

When the United States entered World War I, Kieran enlisted in a New York volunteer engineer regiment.5 It became the Eleventh Engineers (Railway) and shipped out to France on July 14, 1917; its members were among the first 20,000 Americans to land overseas. The regiment provided engineering support behind the lines in the deadliest sectors of the fighting in France but Kieran recalled, “I never experienced anything worse than a good shaking up now and then when a shell landed too close for comfort.” Kieran was discharged as a staff sergeant on May 5, 1919, after 23 months in the service, nearly all of them overseas.

“As soon as I was turned loose by the army,” Kieran recalled, ‘I married the girl I left behind me,” Alma Boldtmann, a native New Yorker of French and German descent who had been chief of the telephone operators at the Times. They settled in the Riverdale section of New York and raised three children: James M., John Francis Jr., and Beatrice.

Kieran returned to writing golf for the Times and also got experience reporting track meets, basketball, amateur boxing, fencing, billiards, “and even dog and cat shows.” By 1922, however, an opportunity to work with Grantland Rice and to have his own bylined column and a baseball beat prompted Kieran to join the New York Tribune. He relished the travel aspect of the work, using his mornings to learn about the cities he visited and rekindle his interest in nature. Of Pittsburgh, he recalled: “Just over the outfield fence in Forbes Field lay Schenley Park through which I roamed regularly with my field glasses on the alert. It was a good place to look for migrant warblers in May and September.”

The Tribune baseball beat carried with it recurring duty as official scorer at the Polo Grounds. During a May 15, 1922, Tigers-Yankees game there, Kieran, the old college shortstop, charged Yankee shortstop Everett Scott with an error on a ball hit by Ty Cobb. Sportswriter Fred Lieb, seated at a distance from Kieran and without consulting him, scored the play a hit in his Associated Press box score. At the end of the season, with Cobb at either .401 or .399 depending on the May 15 scoring and with American League President Ban Johnson firmly in Cobb’s corner, Kieran and other New York writers were unsuccessful in their contention that the official scoring should prevail. Although even Lieb reversed himself, Johnson didn’t. Despite the local support, the incident left Kieran disenchanted with a lack of support from his national group, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, and with the baseball establishment.6 Kieran never lost his love for the game he played as a boy and collegian, however, and as late as 1939 worked out in uniform with the Red Sox in spring training.

In 1925, lured by William Randolph Hearst’s bankroll and the overtures of Damon Runyon, Kieran left the merged Herald Tribune for his own column, “Wild Oats and Chaff,” at the New York American. Although he was able to use the column to indulge his penchant for light verse, he was never comfortable with Hearst’s mercurial management style and was soon “looking for the escape hatch.” Birchall, his old confidant at the Times, had become managing editor there, and in December, 1926, hired Kieran to not only return, but also to launch the Times’ first-ever bylined column.

Thus began “Sports of the Times,” appearing under Kieran’s name on January 1, 1927, and still a staple, through Kieran, Arthur Daley, Robert Lipsyte, Dave Anderson, Red Smith, and George Vecsey.7 Kieran used the column assignment, which he deemed “a real cushy billet,” to indulge what sportswriter Frank Deford describes in his 2012 memoir Over Time as an excellent trait for a writer: “A fellow who may have deep abiding personal interests, but who has a natural curiosity for almost anything he doesn’t know.”

“I could choose my own topics, go where I wanted and wrote as I pleased within reasonable limits,” Kieran recalled. “This gave me great freedom of movement and a wide choice of subject matter.” He used this freedom and the Times resources for travel to London and Paris. “I rambled scandalously and touched on topics that rarely found their way into the sports section of any reputable newspaper.8 I carried on scandalously in light verse, too.”9

And nature continued to beckon. “Whenever I went to cover outdoor competition of any kind–baseball, football, tennis, golf, polo or horse racing–I kept my eyes open and saw more things than my press badge called for. On trips to cover ball games in St. Louis and Cincinnati I learned the western meadowlark’s song is much sweeter than that of our eastern meadowlark and that there are noble mossy-cup oaks in Forest Park in St. Louis. A man would get a good grounding in botany simply by identifying all the native shrubs and trees at the Saratoga racing plant.” Kieran used similar observations from his walks around New York City to do a series of nature articles for the Times Sunday Magazine section.

Kieran’s broad expertise and wit were becoming well known around New York. In May 1938 he received a call from Dan Golenpaul, producer of a new NBC Radio show, “Information Please.” The panel and audience participation quiz show had been in existence about a month, and Kieran recalled “they were seeking new panelists. They had discovered that not all the original quartet could go the distance.” The studio and radio audiences wanted to hear about sports, but only Franklin P. Adams, a fellow-columnist friend of Kieran’s, knew anything about the subject, and even his knowledge was limited. After an off-the-air test run, Golenpaul snapped up Kieran to join Adams and acerbic pianist-composer-actor Oscar Levant on the regular panel, which also had a fourth guest panelist each week. His beginning $40 stipend ultimately grew to $200 a week for a half-hour unrehearsed appearance.

Moderated by the urbane Clifton Fadiman, the program became nationally popular in a matter of months. Kieran in 1964: “I may be prejudiced–I’m sure I am–in saying that it was the most literate popular entertainment program ever to go out over the air on radio or television.” Kieran’s Boston Globe obituary observed “he became one of the most popular persons in the entertainment world,” and “his breadth of interest and depth of knowledge lifted him from the realm of sports writing into national prominence.” That the show was in Kieran’s recollection “as much a comedy as a quiz show,” only boosted its appeal as the panel toured the country during World War II promoting war bond sales and Kieran reprised the show’s format in several USO appearances overseas.

Even as he explored arcane subjects within the broad landscape “Sports of the Times” allowed, baseball was never far from Kieran’s mind. He was intrigued by fellow polymath Moe Berg, a philology and law school graduate with reading knowledge of more than half a dozen languages. “Perhaps it was the incongruity of such an erudite young man making his living playing major league baseball that amused Kieran. For many years the columnist kept his readers informed about ‘Professor’ Berg’s progress through the nation’s research libraries as well as his activities behind the plate, making Berg one of the widely recognized players of his era, despite his lowly position as a third-string catcher,” William Curran observes in his Gale’s profile. Berg reached such celebrity that he, described by Kieran as “baseball’s One-Man Mystery,” appeared as the guest panelist on “Information Please” three times.

Major leaguers recognized Kieran’s unique combination of knowledge and skills. Lou Gehrig’s Yankee teammates called on the columnist to write the verse engraved on the commemorative award they presented to their stricken friend during his memorable retirement ceremony at Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939.10

By late 1941 Kieran had already published his first three books and was still active with “Information Please.”11 But producing 1,100 words a day, seven days a week, for “Sports of the Times” burdened him to the point that he left the Times for less-rigorous work at the New York Sun. There, he mixed nature and sports in his “One Small Voice” column. Although it was shorter and appeared less frequently than his former Times column, “One Small Voice” was widely syndicated and reached a broader national readership. Still, although working under less stress, he suffered a minor heart attack while at the Sun. After Alma died in 1944, Kieran resigned and ended his newspaper career.

Kieran’s loyal radio public could finally see “the short, trim, pixie-ish man with jug-handle ears, awkwardly angular face and impish eyes” whose “Brooklyn taxi-driver accent” they had enjoyed for years when he took on a television documentary series in 1949. On “John Kieran’s Kaleidoscope” he hosted and narrated a collection of short- subject films on astronomy, natural history, chemistry, physics, biology, atomic energy, and other wide-ranging topics that had been made for movie theaters. Edited for television, the 15-minute shows appeared as 104 weekly originals. “[Kaleidoscope] never made the big league, the New York stations, but ran in many other big cities and often the whole series was re-run under the same sponsorship for another two-year term,” Kieran recalled.

“Information Please” remained on radio until 1948 with Kieran still on board. He returned as the only original panelist when the show made a three-month foray into television in 1952 as a summer replacement.

Kieran had remarried in 1947–to Margaret Ford, a Boston Herald feature writer 12 years his junior. While in post-newspaper semi-retirement in New York from 1945 through 1952 he briefly edited Golenpaul’s new Information Please Almanac, but turned his primary literary attention to writing about nature. Having become “a serious though self-trained naturalist,” according to his Gale’s profile, Kieran published two books on birds, another on wildflowers, and another on general nature. His birds-wildflowers-trees trilogy was completed in 1954.

With Kieran’s now-flexible schedule, he and Margaret began to explore her home area around Boston for retirement. When his New York radio and television obligations ended in 1952 they moved to Rockport, Cape Ann, Massachusetts, where Kieran’s second-floor study, displaying his four original Audubon prints, overlooked the Atlantic Ocean.12 He was free to roam the surrounding woods, bogs, and shores, observing the ever-changing natural landscape and bird life.

Margaret enjoyed her hobby of watercolor painting while Kieran, whose lifetime credo was “I am a part of everything that I have read,” continued to read voraciously, study nature, and write. He recalled in Not Under Oath that Margaret “has given me the best years of her life–and mine.” With Margaret, Kieran co-authored a biography of naturalist John James Audubon in 1954. And busy as he was, Kieran found time to write the entertaining Not Under Oath, published in 1964.

Free to concentrate on full-time nature writing, in 1959 Kieran published A Natural History of New York City, which chronicled his many weekend walks through Van Cortlandt Park and highlighted the more than 28,000 acres of public park land within the city limits. The work won the 1960 John Burroughs Medal for nature writing, and in 1988 Van Cortlandt Park named its trail around the park’s lake and freshwater wetlands area the John Kieran Nature Trail. His adopted hometown of Rockport honors Kieran with the John Kieran Nature Preserve and The John Kieran Collection, which includes his donated books, at the Rockport Public Library.

In 1973, as he joined an elite circle honored “for meritorious contributions to baseball writing”–including Ring Lardner, Grantland Rice, Damon Runyon, and J. G. Taylor Spink himself–Kieran most likely enjoyed the irony when the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voted him the Spink Award, 51 years after the national group had failed to support his official scoring decision in the Cobb-Ban Johnson incident. His citation, presented at Hall of Fame Induction Day ceremonies on August 12, 1974, proclaims: “Did most to prove to newspaper readers and radio listeners that sports writers’ knowledge was not confined to pressbox and clubhouse,” and concludes, “Result: Fountain of information that brought distinction to Kieran and craft.” Kieran’s Spink Award came on the heels of his election to the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association Hall of Fame in 1971.

Kieran also received the President’s Medal from Fordham University in 1981. “The stumping of the scholarly John Kieran [on “Information Please”] was a singular occurrence,” was part of the award citation.

He died in Rockport later that year, December 10, 1981, at age 89.

Writing 17 years earlier, Kieran had conveyed in his Epilogue to Not Under Oath a distinct sense of the eternal promise he found in the natural surroundings he loved: “But the tide of the young year has turned. The dark mornings are getting lighter each day. The sun lingers a little longer each afternoon. The buds are beginning to swell on the poplar and the alder catkins are lengthening in the frozen swamp. Soon in the hush of dusk over the inland meadows we will hear the first shrill quavering notes of the peepers–the dauntless invisible heralds of ever-returning spring. Cheerfully I echo Browning; ‘Grow old along with me! The best is yet to be, the last of life, for which the first was made . . .’ Reader, farewell. May your life and loves be as happy as mine have been.”13

Acknowledgment

Gabriel Schechter, SABR, Cherry Valley, New York.

Sources

Frank Deford, Over Time: My Life As a Sportswriter (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2012), 136.

John A. Garrity and Mark C. Carnes, ed., American National Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 658-659.

Jerome Holtzman, ed., No Cheering In The Press Box (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1973), 34-45.

John Kieran, Not Under Oath (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1964).

Fred Lieb, Baseball As I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann, and Geoghegan, Inc., 1977), 68-71.

“John Kieran,” Weekly Shout-Out, Montgomery County Public Library, Rockville, Maryland, October 31, 2008, December 3, 2008.

George Vecsey, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times,” December 16, 2011.

Boston Globe, John Kieran obituary, December 11, 1981.

New York Times, John Kieran obituary, December 11, 1981.

The Sporting News, July 4, 1970, December 22, 1973, August 31, 1974, May 3, 1980.

Baseball-Almanac.com

BaseballHallofFame.org

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Cyber-Nation.com (John Kieran quotation entry)

MyOldRadio.com (“Information Please” guests log)

FindAGrave.com (John Kieran entry)

NYHistory.org (John Kieran entry, Bill Shannon’s Biographical Dictionary of New York Sports)

Retrosheet.org

VanCortlandt.com (John Kieran Nature Trail entry)

William Curran, “John Kieran,” Gale’s Dictionary of Literary Biography Database, Gale Research, Detroit, Michigan, 1996.

Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York, Excerpts from John Kieran file.

John Kieran Papers Abstract, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Notes

1 For the “Scribes,” the exhibit is often, albeit erroneously, called “the writers’ wing” of the Hall. Gabriel Schechter, a former associate in the Giamatti Research Center, notes that there’s no Hall “wing” for writers and broadcasters and that the exhibit area is “generously,” a “nook.” Charlesapril.com, Gabriel Schechter “Never Too Much Baseball” blog, “Unfortunately, I Was Right,” July 26, 2010.

2 “A step up financially but a comedown socially,” Kieran noted in Not Under Oath, his whimsical 1964 autobiography, 35.

3 As early as his first season as a baseball beat writer in 1922, a controversy with American League President Ban Johnson over an official scoring decision, compounded by what Kieran perceived to be lackluster support from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA), left him disenchanted with the baseball establishment, but never the game itself. See also: Note 6.

4 The Tribune had merged with the larger-circulation Herald in 1924, during Kieran’s tenure with the former.

5 The United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917.

6 While Cobb is officially credited with a .401 average in 1922, second in the AL to George Sisler’s .420, it is interesting to note that to the extent “official” box scores exist (Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org) the May 15, 1922, Detroit-New York box shows Scott with his 10th error of the still-young season. Probably preferring to “let sleeping dogs lie,” Kieran did not address the 1922 incident 42 years later in Not Under Oath. See also: Note 3.

7 Vecsey took over the column in 1982 and, although purporting to “step away” in his December 16, 2011, “Sports of the Times,” through January 2013 continues to occasionally write it.

8 Including ancient history, modern art, organic and inorganic chemistry, astronomy, quotations from the Italian sports press, John Keats, Robert Browning, and Virgil, occasional book reviews, and a discussion of Heisenberg’s Theory of Probabilities as applied to the game of three-cushion billiards. Not Under Oath, 39.

9 Examples include poems on the Joe Louis-Max Schmeling bout at Yankee Stadium on June 19, 1936, and their rematch for the heavyweight title on June 22, 1938. Not Under Oath, 39-41.

10 It concludes: “But higher than we hold you, / We who have known you best; / Knowing the way you came through / Every human test. / Let this be a silent token / Of lasting Friendship’s gleam, / And all that we’ve left unspoken; / Your Pals of the Yankees Team.”

11 The books were The Story of the Olympic Games: 776 B.C. – 1936 A.D. (1936), John Kieran’s Nature Notes (1941), and The American Sporting Scene (1941).

12 For a time through 1948, Kieran headed the Audubon Society.

13 Kieran’s wife Margaret survived, as did all three children from his prior marriage. He is buried in Beech Grove Cemetery, Rockport.

Full Name

Francis Kieran

Born

August 2, 1892 at New York, NY (US)

Died

December 9, 1981 at Rockport, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.