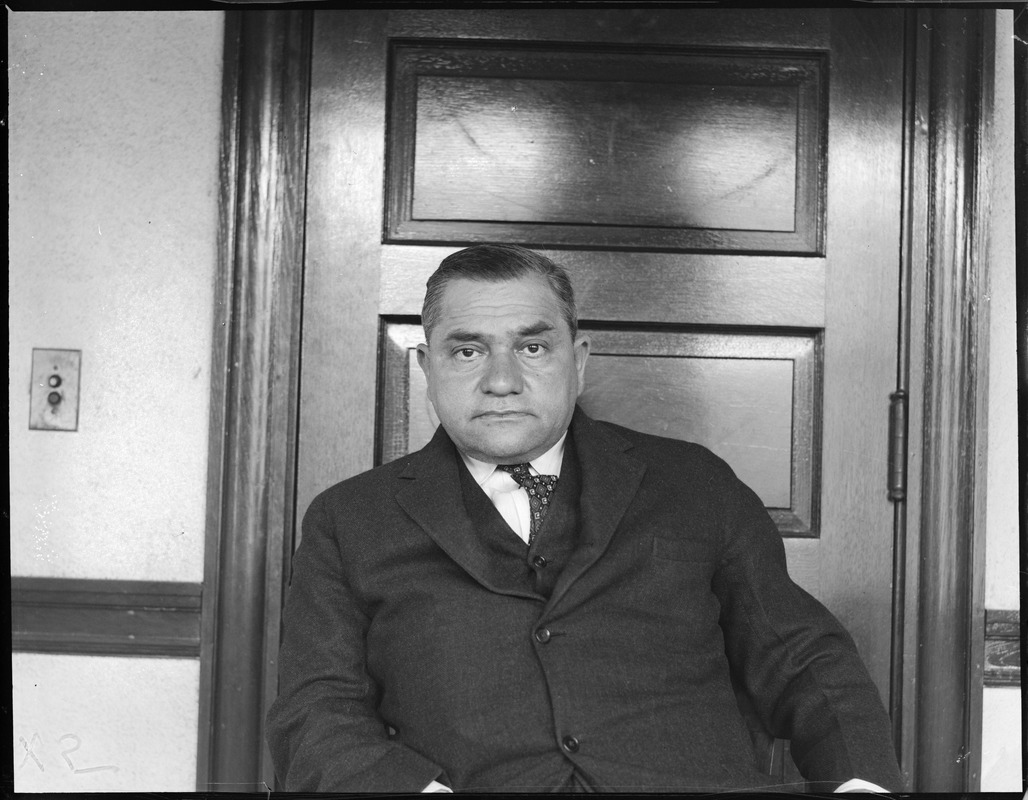

Judge Emil Fuchs

“I felt I’d be happier trying to make a living from baseball than any other business I know,” Judge Emil Fuchs said.1 “Happy” would not describe the Judge in the baseball business world: he lost nearly everything he had as owner of the Boston Braves, unsuccessfully striving to make them into a contender from 1923 to1935. But his business losses did not detract from his overall demeanor. “He had a passion for baseball,” Carolyn Fuchs, the Judge’s granddaughter, recalled. “He wanted those fans to be happy. In a tale of two cities, he worked in New York as a successful lawyer and commuted to Boston when getting involved with the Braves. He not only loved his work in baseball but loved Boston as well.”2

“I felt I’d be happier trying to make a living from baseball than any other business I know,” Judge Emil Fuchs said.1 “Happy” would not describe the Judge in the baseball business world: he lost nearly everything he had as owner of the Boston Braves, unsuccessfully striving to make them into a contender from 1923 to1935. But his business losses did not detract from his overall demeanor. “He had a passion for baseball,” Carolyn Fuchs, the Judge’s granddaughter, recalled. “He wanted those fans to be happy. In a tale of two cities, he worked in New York as a successful lawyer and commuted to Boston when getting involved with the Braves. He not only loved his work in baseball but loved Boston as well.”2

His passion didn’t lead to financial success, however. Fuchs was a fan first and was beloved by the Boston community as a caring philanthropist and man of integrity while his team was an annual disappointment. He certainly tried, marketing the game to female fans and children, tapping into the new medium of radio, fighting for Sunday baseball against New England’s Puritan culture, and saving money by naming himself manager. Fuchs operated in the shadow of Tom Yawkey, the wealthy owner of the Red Sox across town, who had gobs of money to acquire superstars and renovate Fenway Park. “Fuchs was a fan who tried hard to be an owner…to be a manager, a financier, and a public-relations man,” wrote Harold Kaese. “He was successful as a public-relations man.”3

Emil Edwin Fuchs was born on April 17, 1878, in Bromberg, Germany, to Hermann and Henrietta (Wollenberg) Fuchs, Orthodox Jews who immigrated to New York City. Hermann arrived in 1883 and worked as a chemist for the Eimer & Amend Company and later ran his own syrup manufacturing business.4 Henrietta and her five sons joined him a year later. Emil had four brothers: Berthold, Oscar, Benjamin, and William. The family lived on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in University Settlement housing, a place where the swelling immigrant population could find refuge.5

Fuchs first learned to play baseball as a boy at Maspeth Park in Queens. At 13 he became the catcher on the University Settlement House team. He later played for the City College of New York, then minor league ball in the short-lived New Jersey State League in 1897. An injury ended his playing career.6 Fuchs attended evening classes at New York University Law School, passed the bar exam, and began his law practice in 1899.

Fuchs worked his way up to prominence through public service in New York City, clerking for the Deputy Attorney General before holding that position himself from 1902 to 1906.7 His political connections included prominent Democrats, such as future mayors Al Smith, Jimmy Walker, and Fiorello LaGuardia. Fuchs’s title of “judge” came from his one term of service as New York City Magistrate 1917-1918.8

Fuchs married Aurelia “Oretta” Marcovich on June 15, 1909. Oretta was the daughter of Henry and Rose (Trauber) Marcovich, immigrants from Jassy (also called Lassi or Lasi), a city in eastern Romania.

Fuchs operated an office on Chambers Street in lower Manhattan and was involved in many prominent law cases. He gained the reputation as an expert in election law. At one time Fuchs even represented humorist Will Rogers when the legend worked for the Ziegfeld Follies. The Judge allegedly wrote up the contract when Rogers purchased his first horse. In 1919 he defended legendary gambler and mob kingpin Arnold Rothstein, who held a high-stakes poker game with 19 other gamblers. When the police knocked at the door, Rothstein fired bullets, injuring officers, then fled to the fire escape. He was apprehended but, no surprise, the other gamblers claimed he was never there. Rothstein paid bail for all 20 of them. With no witnesses or other evidence that Rothstein fired the gun, Fuchs called for dismissal. “The record is barren of any evidence tending directly or indirectly to connect the defendant with the commission of any crime” he said.9 Rothstein was freed, and Fuchs never lived down the fact that he had successfully defended the man who fixed the 1919 World Series, dubbed the “Black Sox Scandal.”

Fuchs represented New York Governor Charles S. Whitman in a failed ballot recount in his re-election bid.10 “The Judge represented the powerful and the powerless,” his son, Robert, wrote in 1998. “Saints and sinners, millionaires and misfits, toting up an enviable record. He was one of the world’s most cosmopolitan men in the most cosmopolitan city on the face of the earth.”11 Fuchs also represented the New York Giants, including outfielder Benny Kauff in an automobile theft case, and a drunken close friend, John McGraw, who was guilty of connecting with a right cross.12

McGraw and Fuchs were socializing at the Lambs Club in New York City, a popular city attraction.13 Also present were actor and songwriter George M. Cohan, famous for the WWI song “Over There,” and noted concessions operator Harry M. Stevens, who made a fortune when he realized a hotdog at a ballgame was a winning idea.

“Why, there’s George Washington Grant,” McGraw exclaimed, pointing out the owner of the Boston Braves. “Did you know you can buy his ball club for half a million dollars?”14 Grant was the “derby-wearing, cane-carrying,” prosperous cinema owner who had owned the Braves since 1919 and was another friend of McGraw.15 Grant, a successful promoter of theaters and motion pictures, had been losing money since he had purchased the club. Once asked about selling the club, he remarked, “I will sell anything I have but my family, if I got my price.”16 McGraw, turning to Fuchs, asked, “Judge, why don’t you buy it?” Fuchs showed interest, with one condition.

“John, I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” Fuchs said. “One of my friends and idols is Christy Mathewson, in whom I have not only admiration but every confidence.” Matthewson, the legendary Giants pitching ace, won a remarkable 373 games and compiled a 0.97 ERA in 11 World Series games. At that time, Matty was retired from the game and suffering from tuberculosis due to his service in World War I. He lived at Saranac Lake in upstate New York under the care of physicians. “I’d buy the Braves if I could continue my law practice and he’d be general manager and president.”17 Mathewson accepted the position of club president and treasurer despite his doctor’s warnings that it would cut short his life expectancy.18 James MacDonough, a New York banker, and Albert H. Powell, a millionaire through coal and real estate, also joined the duo in purchasing the Braves for a reported $300,000.19 Fuchs became vice president. Not much changed on the field, however, as the Braves finished 1923 at 54-100, 41½ games behind the Giants.

Fuchs and Mathewson sought a more entertaining product to increase revenue. They signed a contract with Marcus Loew, motion picture entrepreneur and vaudeville magnate. The Boston Herald reported that Loew was to “stage night motion pictures, band concerts, fireworks and vaudeville at Braves Field this summer.”20 On June 25, a crowd of 8,000 came to enjoy the dancing, the stars of stage and screen, and the movie Trifling with Honor shown on two large screens. The events continued throughout the summer of 1923, but then suddenly stopped, likely due to financial reasons.21 The 1923 season was also the beginning of Ladies’ Day at Braves Field, when women could enter the ballpark free of charge.22 This would become a regular feature at both Braves Field and Fenway Park for years to come.

The 1924 Braves finished 53-100, but the team improved in 1925 to 70-83, their most wins in four years. The inaugural baseball game broadcast from Boston was heard on WBZ from Braves Field on Opening Day, April 14.23 While many club owners hesitated at the new technology, Fuchs saw the medium’s great potential, and was willing to pay for the broadcasts out of his own pocket.24

Fuchs was in Pittsburgh for the 1925 World Series when he learned Mathewson had died.25 The Boston Board of Directors met on October 21 and officially installed Fuchs as club president.26 The club suffered two awful seasons in 1926-27 (66-86 and 60-94).

In August 1926, Fuchs bought out the stock holdings of Powell. “The Boston Braves franchise is now considered to be worth a million dollars,” the Boston Herald reported.27 In May of 1927, Fuchs sold his extra shares to Charles F. Adams, V.C. Bruce Wetmore, and Charles F. Farnsworth, with Adams being the major shareholder. Adams was well known in the Boston area for success in the grocery business and as president of the Boston Bruins hockey club.28 His success would one day lead to his induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame.29

The new ownership was committed to spending money, but no one expected the shocking trade in which the Braves acquired six-time National League batting champion Rogers Hornsby. His reported $35,000 salary was “more money than any two non-managing Boston players ever received,” according to Herald sportswriter Burt Whitman.30 Fuchs and Adams needed to “dig down deeply as a result of the trade. But they are living up to their promises to strengthen the Braves when they could see a means of doing it, regardless of the cost.”31 Hornsby also became the player-manager early in the season, replacing Jack Slattery.32

Fuchs moved in the fences at Braves Field, hopefully to provide more home runs for the Braves. He said Braves Field was “where the outfielders needed motorcycles to retrieve drives between the outfielders.”33 Soon, however, the opponents were the ones slamming the home runs, causing Fuchs to add a wire netting.34 The anonymous writer of the “Bob Dunbar” column in the Boston Herald joked the new slogan of Braves Field should be “Buy a 75-cent left field bleacher seat and get a baseball free.”35 In June, a 30-foot canvas was erected above the left-field fence.36 In July the fences were moved back again.37

Hornsby won another batting title, but the Braves finished 50-103. Needing cash more than a legend, Fuchs sold Hornsby in November to the Cubs for $200,000, the most money ever spent in baseball history at the time, and “five machine-guns from Chicago,” the witty Will Rogers joked.38

November 1928 was quite the month. On the ballot in Massachusetts was a referendum on allowing professional sports to be played on Sunday. Massachusetts law dating from 1692 restricted recreation on Sunday.39 In 1920, the law was tweaked to allow amateur sports to be held on Sundays with some restrictions.40 Local towns were also free to make their own laws concerning Sunday sports.41 Fuchs and Adams supported a grassroots movement to collect signatures to get the issue on the ballot.42 The plan failed on a clerical error in 1926, but voters approved the measure in 1928.43 The plan now had to pass the Boston City Council, and Fuchs and Adams claimed they had been solicited for bribes by the council for favorable votes.44 The Boston Finance Commission also discovered that the Outdoor Recreation League, which supported Sunday sports and to which Fuchs contributed, had illegally spent $30,000 on campaigning, with all or most of the money coming from Fuchs while questionable donor names were listed. Around 5,000 tickets to Braves games were found to have an advertisement on the back for a political candidate who favored the Sunday bill.45 The Braves were fined $1,000 in municipal court for “charging the expenditure of money to influence the vote of a question submitted to the voters.”46 Adams sought to salvage the Judge’s reputation before the Boston Finance Committee by submitting letters from notable politicians, baseball icons, and others who are household names even today, such as Charles Schwab and Robert Guggenheim.47 Fuchs did later admit he probably contributed $200,000 of his own money towards the Sunday bill.48 But, Sunday baseball was now a reality in Boston.

Fuchs could put his mind to other matters, like becoming manager of the Braves. “These are the ingredients of the most sensational and most unusual baseball story which has broken in Boston in many and many a year,” Burt Whitman wrote in the Boston Herald.49 Fuchs figured if the Braves were going to have another losing season, “I can do it a lot more cheaply.”50 He surrounded himself with knowledgeable baseball people such as coach Johnny Evers. “If I don’t make good,” Fuchs reportedly said, “no one will realize it quicker than I, and it will be perfectly simple for me to remove myself as manager.”51 It wasn’t that simple. While the Braves started 9-4, they quickly fell apart. But it was surely memorable. When Evers asked what his manager thought a batter should do on a 3-1 count, take or swing, Fuchs responded, “Tell him to hit a home run.”52 The Braves finished 56-98, their sixth straight losing season since Fuchs took primary ownership. Attendance improved to 372,351, thanks in part to the Sunday games, which accounted for a quarter of the attendance.53

As 1930 rolled around, according to the census that year, the Fuchs family lived in an apartment on Riverside Drive in Manhattan. The family included Oretta, sons Robert S. and Job E, daughter Helen, and a servant named Elizabeth Turpin. Fuchs also decided he had enough of managing and brought in veteran Bill McKechnie, who had prior success in Pittsburgh and St. Louis.54 The team improved to 70-84, helped by rookie slugger Wally Berger, then fell to 64-90 in 1931 but saw a franchise-best 464,835 fans pour into Braves Field, helped by a 2-for-1 Sunday doubleheader deal.

The team finished 77-77 in 1932, their best record since 1921. The 507,606 fans, half of which attended Sunday games, saw the Braves in the pennant hunt into August. Fuchs also held a “Jobless Carnival” to raise money for the unemployed.55 The barnstorming bearded men of the House of David visited for an exhibition game, bringing their portable lighting system. It was the first baseball game played by artificial light in Boston.56 According to Robert Fuchs, the success of the Braves attracted the interest of automobile tycoon Henry Ford, who visited a Braves-Tigers exhibition game and made the Judge an offer to buy the Braves. “My father would not have sold his then first-division team to Henry Ford when that industrial titan personally scouted the Braves,” Robert recalled, citing his father’s love of Boston. “Ford would have moved the Braves to Detroit.”57 Fuchs was also once approached with an offer by Joseph Kennedy, father of future President John F. Kennedy.58

Fuchs increased the number of lowest-priced seats at Braves Field in 1933 and extended the 1,500-seat 50-cent “Jury Box” section in right field to 5,200 seats. The Judge also changed the regular Ladies’ Day Games from Friday to Saturday, since many women were working on the weekdays.59 He also changed the times of Saturday games to 2 PM “out of consideration of women employed in offices and department stores, and who have a week-end half-holiday.”60 Fuchs had another reason for the time change: stockbrokers. “They come into town to watch the tickers from 10 to 12 on Saturday,” he said. “If they could grab a quick lunch at that time and come to the ballpark, they would. Rather than wait around until three o’clock for the game to start, they go home to lunch. Once they get home, they can’t find an excuse to come back into the city. They get nailed to mow the lawn or hoe the weeds out of the garden.”61

The Braves broke their attendance record again in 1933 (517,803) and hung around the pennant race until late August. On August 31 fans packed Braves Field for a six-game series with the Giants, who had a six-game lead. A Friday doubleheader on September 1 saw 60,000 pennant-starved fans pack Braves Field while another 15,000 were turned away.62 The Braves’ 83 wins in 1933 were their most since 1916. But their attendance would not reach such heights again until 1946, the last season in which the Braves would outdraw the Red Sox. The Red Sox’ millionaire owner Tom Yawkey was renovating Fenway Park and buying star players such as Lefty Grove, Joe Cronin, and Jimmie Foxx. The Judge had new competition in his own city. The Braves continued to struggle. NL owners met on June 20 to discuss details of the first annual All-Star game and also discussed Fuchs and the Braves’ finances.

The Braves broke their attendance record again in 1933 (517,803) and hung around the pennant race until late August. On August 31 fans packed Braves Field for a six-game series with the Giants, who had a six-game lead. A Friday doubleheader on September 1 saw 60,000 pennant-starved fans pack Braves Field while another 15,000 were turned away.62 The Braves’ 83 wins in 1933 were their most since 1916. But their attendance would not reach such heights again until 1946, the last season in which the Braves would outdraw the Red Sox. The Red Sox’ millionaire owner Tom Yawkey was renovating Fenway Park and buying star players such as Lefty Grove, Joe Cronin, and Jimmie Foxx. The Judge had new competition in his own city. The Braves continued to struggle. NL owners met on June 20 to discuss details of the first annual All-Star game and also discussed Fuchs and the Braves’ finances.

On July 8, James C. O’Leary of the Boston Globe reported that the Braves were in financial turmoil and a shakeup in ownership was inevitable. “Some time ago,” O’Leary wrote, “according to the best available unofficial information, Judge Fuchs, needing ready money — as who hasn’t in these times? — borrowed it and put up as security part of his Braves stock.”63 Fuchs had borrowed money from Adams, the figures of which varied from report to report, but were around $250,000. Adams loaned Fuchs the money in cash, not even writing up any paperwork until later. “If I didn’t have confidence in you, I wouldn’t join with you,” Adams said.64 Fuchs put his own stock up as collateral.65 The first payment due was reported by both the Globe and the Herald to be $100,000.66

The Braves of 1934 finished in fourth place at 78-73 but attendance dropped to 303,205, a 214,598 decline. Fuchs reported the Braves had made $500,000 between 1929 and 1933, but most of the revenue had been put right back into the club. The team was a financial disaster by the end of 1934.67

Horse- and dog-racing were a growing craze around the country at the time. Both Rockingham Park in Salem, New Hampshire, and Narragansett Park in Rhode Island were attracting massive crowds. Massachusetts voters passed a referendum allowing pari-mutuel betting on both horses and greyhounds.68 Fuchs envisioned using Braves Field to host greyhound racing.69 A five-sixteenths of a mile portable track would run along the outer edges of the field. “It would not interfere with baseball at all,” Fuchs said.70 The Braves would continue to play baseball during the day and a separate organization would host the dog races at night. Although no horse racing track could come within a 15-mile radius of the Boston city limits, entrepreneurs were seeking greyhound racing permits. Fuchs and the Braves Board of Directors submitted the application.71

Fuchs had previously spoken with Baseball Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis concerning the greyhounds. Landis replied that he would “look into it.”72 Fuchs considered Landis to be open to the idea and not opposed. When Fuchs’s plans were revealed to the press, however, Landis changed his tune and threatened to quit if such a thing became a reality.73

“Absolutely preposterous,” was the similar response from Ford C. Frick, the NL President-elect.74 “It is entirely at variance with the principles for which baseball has battled so strenuously…Organized baseball has outlawed players for gambling and it is ridiculous to conceive that baseball now could permit a sport founded on gambling to move into the same premises with it.”75 The Associated Press reported that sentiments from club owners were also negative toward the plan.76

“It looks as though I’ve already talked too much,” Fuchs said upon arriving in New York City for baseball’s winter meetings. “I am not combating anybody. In Boston we have a proposition that looks very good to us and one that will in no way cast any reflections on baseball. But I am still confident that when other owners have heard my complete story they will take another view of the situation.”77 Another issue was the lease on Braves Field. The club paid $40,000 per year in rent to the estate of former team owner James Gaffney. The Braves would have to sub-lease the field, adding another complication to the plan.78

Sensing the opposition, Fuchs never let the owners even vote on his proposal. “Nothing will be done by me which will embarrass baseball or the National League,” he said after meeting with NL club owners. “Under the constitution of the National League, betting, legal or otherwise, is prohibited in its ballparks, where baseball is played. I have and always will abide by the constitution of the National League.”79

Soon after the winter meetings, Fuchs revealed that he owed $289,000 to Adams but had paid off $210,000 of it.80 But the issue of dog racing didn’t go away. In January 1935, the Boston Kennel Club submitted an application for a license to run the dog races at Braves Field, ignoring the negative opinions from the National League.81 The Commonwealth Realty Trust, the holding company of the Gaffney estate and the current landlords of Braves Field, even told Ford Frick that the league had no authority in such matters and believed dog racing was “a better investment in the way of a lease than baseball.”82 Commonwealth Realty also revealed that the Braves had violated their lease through late rental payments. “We no longer consider the Braves as our tenant,” said Arthur C. Wise, treasurer. “They have not lived up to the terms of their lease and we have declared it broken. We are now negotiating with the Boston Kennel Club, Inc., and a lease is in the process of being written.”83 If such were true, the Braves would be homeless.

Rumors then began that Fuchs could work out a deal with Yawkey to use Fenway Park when the Red Sox were idle or on the road. Yawkey had no such intentions. “Fenway Park is not available as a place of refuge,” he affirmed.84 Baltimore and Montreal were both mentioned as cities longing for a major-league franchise that would gladly welcome the Braves. 85 Frick called an emergency meeting of National League club owners on January 18. After a long session, a resolution was reached. “We believe that the Boston baseball public will be entirely satisfied with the solution to the problem,” read the statement from Frick, Fuchs, and Adams.86

Frick announced the National League had acquired the 11-year lease on Braves Field from the Gaffney Estate.87 Frick now desperately sought new ownership for the Braves and Fuchs was cooperative. “I am willing to sacrifice my equity in the Boston club if by so doing I can save the other stockholders from any loss through their investment in the club since I have been connected with it,” he said. “I am willing to lose everything I have to insure my associates against loss.”88 “If it is deemed necessary or advisable to get somebody else to run the Braves, who can do it better than I can, I’ll help in every way possible. I want it understood that there is no bitterness on my part and no malice.”89

Fuchs’s financial obligations to Adams were due by February 5 for him to retain control of the team. Financial shortfalls meant there was not enough money to even begin spring training. His friend and Massachusetts governor, James Michael Curley, promised “to use his influence with Boston bankers on behalf of the judge to get an extension of the notes that fall due next week.”90 “It is generally recognized,” wrote the report in the Herald, “that the morale of the players is at a low ebb, and that former patrons of the Braves have turned to the popular Red Sox for their baseball entertainment.”91 Fuchs and Adams met at the Massachusetts State House with Curley, Boston Mayor Frederick Mansfield, and Attorney General Paul A. Dever to discuss financial options for the club.92 The plan agreed upon was to encourage fans to buy advanced sales of tickets and provide cash for the club to get on its feet.93

The plan was an immediate success, with $30,000 raised by February 1 through fans purchasing five-game block tickets. Curley himself bought 100 books, and the Plymouth Rubber Company bought 1000 tickets for Opening Day.94 Additional revenue was planned with opera performances being held at Braves Field in July and August.95

National League owners met again on February 5 and agreed to allow Fuchs to remain as Braves owner. The $43,400 raised at that point in ticket sales and an additional $10,000 in cash was enough money to keep the team afloat. “The judge painted a picture of New England fandom rallying to the support of his Braves,” wrote Whitman. “It is now up to him [Fuchs] to see if he can keep things going.”96 Then, Colonel Jacob Ruppert of the Yankees came calling. Rumors had been floating around the baseball world since at least 1933 that Babe Ruth wanted to become a manager. Ruth had recently managed the team of all-stars that toured the Orient, under the guidance of Connie Mack. Some saw this as a managerial trial for Ruth.97 Ruppert couldn’t afford to jettison the greatest icon in the history of the game and bear the brunt of an unforgiving public. Fuchs’s situation was a gift to Ruppert, who would gladly give Ruth an opportunity to manage. Fuchs was not willing to commit to such an agreement, being content with Bill McKechnie, but was willing to give him the titles of assistant manager and vice president.98 “The contract was a last hurrah in the face of extinction,” Wayne Soini and Robert Fuchs wrote. “It had been years since Ruth could command such a salary and years since the Judge could pay for it, but none of this mattered to either of them. Both looked for a second wind, a rebirth, a miracle at Braves Field in 1935.”99

The Bambino was cheered as a heroic native son returning home. “Boston Fans Hail Ruth’s Return: Babe is Coming to Braves for Three Years as Player and Official,” was the front-page headline in the Boston Globe.100 “It looks like a masterful stroke of business for the Boston club,” O’Leary praised.101 The Herald declared it one of the greatest events in American history. “The old colony has seen many an important paper signed in its 300-odd years history, beginning with the Mayflower Pact, and last night another joined that great list when the Babe signed for three years.”102 The euphoria over the Babe’s return quickly gave way to a still unsustainable financial situation. The farfetched hopes of Ruth saving the franchise were already remote in early May. Fuchs owed payments to Adams on May 13 and August 1. By the time Fuchs gave the Braves a “fight talk” on May 14, threatening major changes unless play improved, the team was already 6-14 and Ruth was hitting .171 with two home runs.103 Ruth felt obligated to try to help Fuchs and the team through his presence as a box office attraction, but confided in friends that he should just retire.

Ruth sought permission from Fuchs to attend a reception on the French luxury liner Normandie, on its maiden voyage, when it docked in New York City. Fuchs refused, saying Ruth’s place was with the team. “I do not have to put up with this sort of treatment,” Ruth blasted. He called a press conference while a game was in progress on June 2. “I will not return to the Braves so long as Fuchs remains in control of the club,” he promised.104 Fuchs had actually informed Ruth of his release on June 1. “I am very sorry that Babe is not more of a sportsman and is not putting the blame where it belongs,” Fuchs said. “He can do his most for baseball right out there on the playing field.”105 The Braves finished the season 38-115 with a .248 winning percentage, the second-lowest percentage of any team in the 20th century.

The end of Ruth also spelled doom for the Judge. Fuchs acknowledged the team was nearly bankrupt. “So far as I am concerned,” he confessed, “I am unable to provide such capital, as I have exhausted every personal financial means. My heart and soul is for Boston and New England. They deserve the best, and it occurred to me that it may be my situation, just described, that is handicapping the course. I am willing to sacrifice the large equity I have in the Braves.”106

The August 1 deadline was approaching and Fuchs hurriedly tried to find a buyer for the Braves. He failed and resigned on that date, turning over full control of the club to Adams. Fuchs’s equity in the club was listed at $400,000.107 The reorganized Braves, briefly called the Bees, would survive in Boston for another 18 years and make it to the 1948 World Series. The franchise would relocate to Milwaukee in 1953 and later Atlanta.

Fuchs was named by Governor Curley as chairman of the Unemployment Compensation Commission of Massachusetts, a role in which he served until 1938. Fuchs made $6,500 a year.108 His expertise in law led him to host a program on WNAC radio entitled “The Social Security Act and How it Affects New England.”109 “I’m in a position which holds open the door to give a little consolation to the fellow who is out of work,” Fuchs said in 1938.”110

Financial problems were still a reality for Fuchs — he filed for bankruptcy in September 1938, reporteing$263,299 in liabilities and no assets.111 In 1939 Fuchs and son Robert opened a law practice together on Beacon Street.112 They practiced together until Robert joined the National Labor Relations Board in 1948 (whether the Judge retired or maintained a practice part-time is unknown). Both the 1940 census and Fuchs’s WWII draft card listed the family living at the Hotel Victoria on Dartmouth Street. In the winter of 1942, Fuchs wrote a column in the Boston Globe entitled, “The Judge on the Bench,” a series of “First-told tales of the diamond…the inside story of big deals…humor, pathos of the great game.”113

Fuchs was still a regular sight at Braves home games until the club was moved to Milwaukee, as well as Fenway Park, Yankee Stadium, and the Suffolk Downs racetrack. “Although his legs were tender,” wrote Hy Hurwitz of the Boston Globe in 1961, “the Judge climbed to the press box roof at Fenway Park last summer. He cherished the privileges extended him by the Red Sox, although he had been a rival club owner at one time.”114

“The Judge,” remembered Murray Kramer of the Boston Record American, “sitting in a corner of the press box with his inevitable cigar and cane, was a familiar figure to every sports writer. His memory was amazing. Any time a situation called for facts out of the past, everybody went to the Judge and he had them stored away in his mind as though he had a filing system there.”115 Fuchs made his way to the Red Sox clubhouse on September 28, 1960, to shake the hand of Ted Williams, who closed out his legendary career with a home run in his final at-bat.116

Judge Fuchs died in Boston of coronary thrombosis on December 5, 1961, after a 10-week illness.117 He is buried at Sharon Memorial Park in Sharon, Massachusetts.118 Oretta was a semi-invalid in their later years and the Judge “was noted for his devotion to her,” the Herald wrote.119 “He was the greatest fan of baseball,” wrote Fuchs biographer Wayne Soini. “He was the Walter Mitty of baseball,” he said, referring to the daydreaming literary character. “Every fan’s fantasy of being the owner or manager of a major-league team became his life, without regret.”120

The Sporting News summarized Fuchs’s legacy well: “His career was not a bright one. There is this, though, to be said. With his own resources, he kept alive a franchise that would have collapsed. He kept it in Boston, where the Braves lasted for almost two more decades before the franchise was moved to Milwaukee. For these efforts, baseball should be grateful to Emil Fuchs, though futile and unrewarding was his role.”121

Each year the Boston Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) awards the Judge Emil Fuchs Memorial Award to a recipient for “long and meritorious service to baseball.”122

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Sources

Special thanks to Cassidy Lent, Reference Librarian at A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York, who provided the file on Judge Fuchs, and to Bob Brady of the Boston Braves Historical Association.

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author benefited from the following:

Baseball-reference.com

Bob LeMoine, “1934: The Reds Go Under The Lights While the Braves Go to the Dogs,” in Baseball’s Business: The Winter Meetings, Volume I: 1901-1957. Ed. Steve Weingarden & Bill Nowlin. (Phoenix: SABR, 2016), 232-239.

Bob LeMoine, “Boston Braves Ownership History,” SABR Team Ownership History Project.

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Harold Kaese. The Boston Braves 1871-1953. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1954), 193.

2 Carolyn Fuchs, interview with the author, March 25, 2019, April 2, 2019.

3 Kaese, 192.

4 “Hermann Fuchs,” New York Times, June 22, 1917: 12; Immigration year is according to the 1910 census.

5 Established in 1886, University Settlement was “a physical, psychological and spiritual haven where people of all ages, from all countries and every walk of life could seek advice, assistance, education or a simple respite from the harsh realities of everyday life,” according to the University Settlement website. Date accessed: July 5, 2018. https://universitysettlement.org/us/about/history/

6 No records seem to exist of the New Jersey State League, which lasted May-June of 1897 and other than some exhibition games listed, no championship games were played. Other sources say Fuchs played on a Morristown team, but no such team is listed in newspaper accounts of the league, which list Elizabeth, Trenton, Milville, Bridgeton, Asbury Park, and Atlantic City. New York Sun, April 13, 1897: 4; A later account said Fuchs sustained a broken bone in his shoulder from a wild pitch, but indicated this was on the sandlot and not in a professional game. “Judge Fuchs of Braves Fame Dies,” Boston Traveler, December 5, 1961: 62.

7 Letter by Fuchs’ son Robert S. Fuchs, addressed to the Baseball Hall of Fame, dated July 24, 1962; “Capt. Herlihy’s Trial,” New York Times, January 10, 1901: 2; “Supt. M’Cullagh’s Charge,” New York Times, February 6, 1902: 16; “Mathot Looks up a Case,” New York Times, August 11, 1906: 9.

8 “Curran Made a Magistrate,” New York Sun, May 4, 1917: 8.

9 Cited in David Pietrusza’s Rothstein: The Life, Times and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series. (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 140-145; “Man Accused of Shooting Two Detectives is Freed,” New York Tribune, July 25, 1919: 18.

10 “Whitman Case Goes to Highest Court,” Ithaca Journal, December 6, 1918: 1.

11 Robert S. Fuchs & Wayne Soini. Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998), 11.

12 “Kauff Released on Bail,” New York Tribune, February 21, 1920: 8; David Jones, “Benny Kauff,” SABR BioProject. Date accessed, June 30, 2018. sabr.org/bioproj/person/4a224847; “Swann Summons M’Graw in Investigation to Learn Cause of Injury to Slavin,” The Evening World, August 10, 1920: 1; Bill Lamb, “New York Giants Ownership History.” SABR Team Ownership Histories Project. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

13 Harold Kaese, 190.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid, 181; Although never proven, the rumor was that Grant had received $100,000 from Giants owner Charles A. Stoneham to purchase the Braves. Grant was close with Stoneham, both having offices on Wall Street and private boxes next to each other at the Polo Grounds. This was one instance among many at the time in which there was an intimate familiarity between the upper managements of the Braves and Giants. Trades between the two teams did little to squash those conspiracy theories, since they always seemed to heavily favor the Giants.

16 G.W. Grant Buys Braves,” New York Times, January 31, 1919: 12; Gus Rooney, “Boston Fans Sorry at Passing of Grant,” The Sporting News, March 1, 1923: 1.

17 Fuchs & Soini, 21.

18 Fuchs & Soini, 24.

19 Some reports had $350,000, while the Associated Press reported MacDonough stated $500,000 (“Sale of Boston Team Involves Over $500,000,” Springfield Republican, February 22, 1923: 10). No official figure was given, but Grant said he “got his price to the last penny of his demands,” Hartford Courant, February 21, 1923: 12; Macdonough’s name is sometimes spelled without the “a.” His divorce proceedings in the 1933 New York Supreme Court minutes omit the “a.” https://tinyurl.com/y85gx9qj

20 “Marcus Loew Shows Matty the Dotted Line,” Boston Herald, May 1, 1923: 23; “Will Utilize Braves Field Summer Nights,” Boston Herald, June 3, 1923: 15.

21 “Electric Layout for Show is Vast. Lighting Loew Entertainment at Braves Field Big Task,” Boston Herald, July 15, 1923: 45.

22 “Women Have a Chance to See Braves Free Today,” Boston Globe, July 20, 1923: 10.

23 “WBZ Will Put Major League Game on Air Today, New Departure,” Springfield Republican, April 14, 1925: 1.

24 Wayne Soini, interview with the author.

25 Michael Hartley. Christy Mathewson: A Biography. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2004), 168.

26 “Judge Fuchs is Elected President of Braves to Fill Mathewson Vacancy,” Boston Herald, October 22, 1925: 13.

27 “Judge Fuchs Buys Out Powell’s One-Third Interest in Braves,” Boston Herald, September 1, 1926: 10.

28 Ibid, 12.

29 “Charles F. Adams: Historical Pioneer.” Vermont Sports Hall of Fame. https://vermontsportshall.com/2013adams.html (retrieved November 15, 2015); Bob Doherty, “The Somerville Times Historical Fact of the Week — January 22,” Somerville Times, January 22, 2014. Accessed July 7, 2018. https://thesomervilletimes.com/archives/46039;

30 Burt Whitman, “Braves Get Hornsby from Giants in Trade for Hogan and Welsh,” Boston Herald, January 11, 1928: 1.

31 Ibid.

32 Burt Whitman, “Hornsby New Manager of Braves. Jack Slattery Resigns From Tribal Berth,” Boston Herald, May 24, 1928: 1.

33 Burt Whitman, “Johnny Cooney Will Begin His Comeback Campaign at the Braves Camp After New Year,” Boston Herald, December 22, 1927: 15.

34 Burt Whitman, “Braves to Put High Wire Net on New Bleachers; Unwise to Move Stands This Year,” Boston Herald, April 29, 1928: 23.

35 “Bob Dunbar” column, Boston Herald April 23, 1928: 9.

36 “Braves to Erect 30-foot Canvas Screen on Top of New Bleachers,” Boston Herald, June 14, 1928: 15.

37 While dimensions varied in the accounts of the time, the left field fence was moved from 402.5 to 320 feet, center field from 461 to 387, and right field from 365 to 310. See Philip J. Lowry’s Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks. (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), 32. Kaese, 205, notes the changes but gives slightly different dimensions.

38 Fuchs & Soini, 54.

39 Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, Vol. I. (Boston: Wright & Porter, 1869), 58; The law stated, “No tradesman, artificer, labourer or other person whatsoever, shall, upon the land or water, do or exercise any labour, business or work of their ordinary callings, nor use any game, sport, play or recreation on the Lord’s Day.”

40 No admission could be charged, events could not be held within 1000 feet of a church building, and games could only be played between 2 and 6 PM.

41 Charlie Bevis. Red Sox vs. Braves in Boston: The Battle for Fans’ Hearts, 1901-1952. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 101.

42 Ibid, 107.

43 “Sunday Sports Vote Ban Asked,” Boston Globe, June 9, 1926: 1; “Sunday Sports Law not to Appear on Ballot,” Boston Globe, September 18, 1926: 1; Bevis, Red Sox vs. Braves, 111; “Hot Talk Banded on Sunday Sports,” Boston Globe, February 1, 1928: 1; “Red Sox and Braves May Play in Boston Sundays,” Boston Globe, March 4, 1928: B56; “Sunday Pro Sports Approved by the State,” Boston Globe, November 8, 1928: 21.

44 “Fuchs Declares Lynch Asked 13 $5000 Bribes,” Boston Globe, January 3, 1929: 1; Bevis, red Sox vs. Braves, 116.

45 “Parts of ‘Sports’ Testimony ‘Look Bad’ to Atty Gen Warner,” Boston Globe, January 5, 1929: 1, 3.

46 “Braves Pay Fine of $1000,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1929: 10.

47 Fuchs & Soini, 131-138; “Vice President Adams in Defense of Judge Fuchs’ Reputation,” Boston Globe, January 23, 1929: 1, 15.

48 Kaese, 207.

49 Burt Whitman, “Hornsby Sold to Cubs for 5 Men and Cash,” Boston Herald, November 8, 1928: 1.

50 David F. Egan, “Rumor Says Fuchs to Quit as Manager,” Boston Globe, June 13, 1929: 28.

51 Kaese, 209.

52 “Judge Fuchs of Braves Fame Dies,”

53 Bevis, 121.

54 Burt Whitman, “McKechnie Signs Four-Year Contract to Manage Braves, Fuchs Announces at Chicago,” Boston Herald, October 8, 1929: 31.

55 James C. O’Leary, “Red Sox’ Big Eighth Defeats Braves, 6-3,” Boston Globe, June 30, 1932: 22.

56 See Bill Nowlin, “The Beards Versus the Braves,” in Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond. (Phoenix: SABR, 2015), 124-126.

57 Fuchs & Soini, 6.

58 Ibid, 120; International News Service, “Movie Star in Mood to Buy Boston Braves,” Lincoln (NE) Star , June 24, 1935: 8.

59 James C. O’Leary, “Braves and Red Sox Announce ‘Ladies’ Day’ Will Be Held at Both Parks on Saturday,” Boston Globe, January 7, 1933: 10.

60 James C. O’Leary, “Boston National League Club to Have 5200 Bleacher Seats at Lowest Admission Price,” Boston Globe, January 25, 1933: 21.

61 Arthur Sampson, “Fuchs Most Rabid Boston Fan,” Boston Herald, December 6, 1961: 49; At the time, the New York Stock Exchange allowed trading from 10am to noon. William Watts, “A Brief History of Trading Hours on Wall Street,” https://marketwatch.com/story/a-brief-history-of-trading-hours-on-wall-street-2015-05-29 Retrieved March 17, 2019.

62 Victor O. Jones, “Boston’s Biggest Crowd Sees Braves Lose Two,” Boston Globe, September 2, 1933: 1.

63 James C. O’Leary, “Roosevelt Aids Fuchs in New Deal on Braves,” Boston Globe, July 8, 1933: 1.

64 Fuchs & Soini, 58.

65 “Buying Interests of Adams, Wetmore,” Boston Globe, July 20, 1933: 10. In his statement to the press, Fuchs said:

I have just made the first payment under an agreement with Charles F. Adams which will enable me to pay off my financial obligation to Mr. Adams and to purchase the stock of the Boston National League Baseball Club, which is now held by both Mr. Adams and V.C. Bruce Wetmore, providing I meet the terms and payments specified in that agreement.

The first time I ever met Mr. Adams was in 1927. No one but a good sportsman would have handed me $200,000 without a receipt or an agreement, and said: ‘When you return with the ball club in three or four weeks, we can get together on the legal documents.’ His object in taking up the interest of one of my former colleagues was his desire to give Boston a winning ball club.

During my entire association with Mr. Adams, he has given me every encouragement, cooperation and financial assistance toward this end. Any statement to the contrary is unfair and untrue. Mr. Adams has personally loaned me money and took over a loan that I had in New York, stating that he desired to have all the Boston baseball stock in Boston. His investment, through his purchase of stock and his loan to me, is very large and substantial. He has drawn neither salary nor expenses.

Now- let’s forget the commercial end of the great game of baseball; let’s endeavor to excel, so that New England may not be neglected nor slighted in having the best in sports, and let Braves Field be the stadium for honest, attractive and wholesome recreation for our people.

66 “Tribal Control to Judge Fuchs,” Boston Globe, July 21, 1933: 20; “Fuchs, in First Payment of $100,000, Moves to Regain Control of Braves,” Boston Herald, July 20, 1933: 20.

67 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Confident League Will Approve His Carrying Out of its Assignments,” Boston Herald, February 3, 1935: 31.

68 “Pari-Mutuel Betting on Horse Races Wins,” Boston Globe, November 7, 1934: 21.

69 James C. O’Leary, “Braves Head Disclaims Attempt to Land Ruth,” Boston Globe, November 12, 1934: 9.

70 “Fuchs Plans Dog Racing at Wigwam; Will Not Interfere With Baseball,” Boston Herald, November 17, 1934: 11.

71 James C. O’Leary, “Braves Directors to Apply For License to Race Dogs,” Boston Globe, November 17, 1934: 5.

72 Wayne Soini, interview with the author; Soini has in his files a letter from Landis to Fuchs which provides this information.

73 Bill Corum, “Landis Intends Quit if Dog-Racing Gets Foothold in Boston,” Lincoln Star, December 1, 1934: 8.

74 Victor O. Jones, “Frick Opposes Fuchs’ Action. Would Bar Dog Racing in Baseball Parks,” Boston Globe, December 8, 1934: 1.

75 “Braves President Plans to Conduct Dog-Racing Track,” Christian Science Monitor, December 8, 1934: 8.

76 “National League Won’t Allow Braves to use Park for Ball Games and Dog Racing,” Associated Press story printed in the Hartford Courant, December 8, 1934: 13.

77 John Drebinger, “Major Problems Confront Baseball Magnates at Conventions Opening Today,” New York Times, December 11, 1934: 30.

78 Burt Whitman, “Red Sox Certain to Make Trades,” Boston Herald, December 9, 1934: 34.

79 Edward Burns, “Night Games Approved by National League,” Chicago Tribune, December 13, 1934: 25.

80 “Fuchs Attacks Rumors He’s Out as Braves Head,” Boston Herald, December 18, 1934: 1.

81 “Seek License to Hold Dog Races,” Boston Globe, January 13, 1935: A29.

82 “Braves’ Lease on Ballpark Broken; ‘Hands Off,’ Frick is Told on Racing,” Boston Herald, January 14, 1935: 1.

83 “Braves Lose Field, Sox Will Not Rent Fenway,” Springfield Republican, January 15, 1935: 13.

84 Burt Whitman, “National League Has Four Options in Braves Case––Seven-Club League, All Games Away, Franchise Sale, Dogs,” Boston Herald, January 16, 1935: 27.

85 James C. O’Leary, “Homeless Braves are Awaiting the Decision,” Boston Globe, January 17, 1935: 1.

86 “N.L. President Calls Meeting of Club Owners,” Boston Herald, January 15, 1935: 1; Burt Whitman, “Owners Agreed on Braves Case,” Boston Herald, January 19, 1935: 1.

87 “Frick Says a Lease is Soon to be Signed,” Boston Globe, January 30, 1935: 16.

88 James C. O’Leary, “National League to Save Boston Braves,” Boston Globe, January 30, 1935: 16.

89 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Confident League Will Approve His Carrying Out of its Assignments,” Boston Herald, February 3, 1935: 31.

90 “League Takes Long Lease on Braves Field,” Boston Herald, January 29, 1935: 1.

91 Ibid.

92 Ibid, 16.

93 James C. O’Leary, “Braves to Keep Their Ball Park,” Boston Globe, January 29, 1935: 1.

94 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Confident League Will Approve His Carrying Out of its Assignments,” Boston Herald, February 3, 1935: 31.

95 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Confident League Will Approve His Carrying Out of its Assignments,” Boston Herald, February 3, 1935: 31.

96 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Remains Head of Braves,” Boston Herald, February 6, 1935: 22.

97 Burt Whitman, “Adams Admits Seeking Ruth Interview,” Boston Herald, December 14, 1934: 1.

98 James C. O’Leary, “Boston Fan’s Hail Ruth’s Return,” Boston Globe, February 27, 1935: 1.

99 Fuchs & Soini, 105.

100 Boston Globe front page, February 27, 1935.

101 Ibid.

102 “Another Important Massachusetts Bay Document,” Boston Herald, May 1, 1935: 40.

103 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Gives Braves Squad Fight Talk; Threatens Major Changes Unless Team Shows Marked Improvement on Road,” Boston Herald, May 15, 1935: 14.

104 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Releases Ruth After Row,” Boston Herald, June 3, 1935: 1.

105 Ibid, 14.

106 “Fuchs Will Sell Equity in Braves if Team, Stockholders Do Not Suffer,” Boston Herald, June 3, 1935: 14.

107 “Fuchs Resigns as Braves Head,” Boston Herald, August 1, 1935: 1.

108 “Heads New State Board,” Boston Globe, September 11, 1935: 1.

109 “Radio Program News,” Boston Herald, January 25, 1936: 9.

110 “600 Gather to Honor Judge Emil E. Fuchs at Testimonial Dinner on 60th Birthday,” Boston Globe, April 25, 1938: 10.

111 “Emil E. Fuchs Files Petition in Bankruptcy,” Boston Globe, September 3, 1938: 3.

112 “223 Pass Bar Examination; 20 Women Included in Group,” Boston Globe, September 15, 1939: 33.

113 Boston Globe, December 11, 1942: 1; The last column was on January 27.

114 Hy Hurwitz, “Judge Fuchs’ Devotion to Game Great, Lasting,” Boston Globe, December 6, 1961: 43.

115 Murray Kramer, “Judge Emil Fuchs Passes Away, 83,” Boston Record American, December 6, 1961: 48.

116 Boston Daily Record, September 29, 1960: 21.

117 Letter by Robert S. Fuchs.

118 “Judge Fuchs, Owner of Braves, Dies,” Boston Globe, December 5, 1961: 47.

119 “Judge Fuchs, Owned Braves,” Boston Herald, December 6, 1961: 52.

120 Wayne Soini, interview with the author.

121 “Fuchs Lost Heavily, Kept Braves Afloat,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1961: 10.

122 Sam Galanis, “Pedro Martinez Wins Boston BBWAA’s Judge Emil Fuchs Memorial Award,” December 22, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2019. https://nesn.com/2014/12/pedro-martinez-wins-boston-bbwaas-judge-emil-fuchs-memorial-award/

Full Name

Emil Edwin Fuchs

Born

April 17, 1878 at Hamburg, (Germany)

Died

December 5, 1961 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.