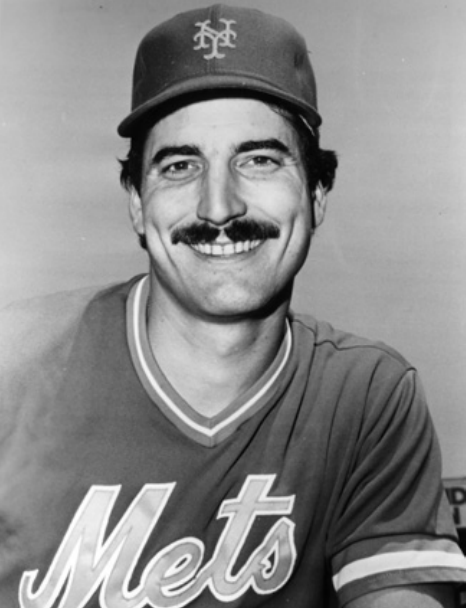

Keith Hernandez

Keith Hernandez, one of the major leagues’ all-time best fielding first basemen, played a key role in the New York Mets’ late 1980s successes. Hernandez, who was originally a St. Louis Cardinal standout, found himself in a predicament when he was traded in midseason to the struggling 1983 Mets. His trade was due to conflicting interests between him and Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog. However, Hernandez would not be denied the thrill of victory for long, as he and his Mets teammates quickly became one of the National League’s most dominant teams.

Keith Hernandez, one of the major leagues’ all-time best fielding first basemen, played a key role in the New York Mets’ late 1980s successes. Hernandez, who was originally a St. Louis Cardinal standout, found himself in a predicament when he was traded in midseason to the struggling 1983 Mets. His trade was due to conflicting interests between him and Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog. However, Hernandez would not be denied the thrill of victory for long, as he and his Mets teammates quickly became one of the National League’s most dominant teams.

Keith Hernandez was born on October 20, 1953, in San Francisco and grew up in nearby San Bruno. He and his brother, Gary, spent hours honing their baseball skills with the help of their father, John Hernandez, who had been a baseball prospect for the Brooklyn Dodgers.1 Keith was a standout athlete at Capuchino High School, but because of disagreement with his coach over playing time, opted to sit out his senior season. After high school, Hernandez attended the College of San Mateo, where he played baseball in 1971 before being drafted in the 42nd round of the amateur draft by the St. Louis Cardinals.

Hernandez began his professional career in 1972 with the St. Petersburg Cardinals of the Class-A Florida State League. He batted .256 with a .388 slugging percentage and 41 RBIs. Late in the season the Cardinals advanced him to the Triple-A Tulsa Oilers (American Association), for whom he played in 11 games. Hernandez showed the Cardinals that his game was developing and he still had much to prove.

In 1973 the Cardinals placed Hernandez with the Double-A Arkansas Travelers (Texas League), where his batting figures were pedestrian but notably he posted a .991 fielding percentage for the second straight season, and was among the top-fielding minor-league first basemen. Late in the season the Cardinals again promoted him to Triple-A Tulsa, where in 31 games his offensive production increased dramatically (.333 batting average, .468 slugging percentage), and his fielding percentage rose to a sensational .997.

It was becoming clear that Hernandez was almost major-league ready and he earned a spot at Triple-A to start the ’74 season. Playing in 102 games for Tulsa, he batted .351 with a .555 slugging percentage and 14 home runs. Hernandez got the call to the Cardinals near the end of August and made his big-league debut on August 30, 1974, against the San Francisco Giants. That night he went 1-for-2 at the plate with two walks and an RBI. In 14 late-season games with St. Louis, he batted .294 with a .441 slugging percentage.

Hernandez spent April and May of 1975 with the Cardinals but his production on offense was woeful. Batting .203, he was sent back to Tulsa in early June. He returned to the Cardinals as a September call-up and by the end of the season he had lifted his batting average to .250. And he was in the big leagues to stay.

While Hernandez made his presence known as a batter, he also quickly gained a reputation as one of the slickest fielders in the game, as evidenced by his 11 consecutive Gold Glove Awards (1978-1988).

In 1979, his fourth full season with the Cardinals, the 25-year-old Hernandez had a breakout campaign, capturing the National League batting title with a .344 batting average, leading the league in doubles (48), and runs scored (116) for the third-place Cardinals (86-76), playing in his first All-Star Game, and sharing the National League MVP Award with Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell.

In the Cardinals’ 1982 world championship season, Hernandez batted .299 and drove in 94 runs. He helped push the Cardinals past the Atlanta Braves in a three-game sweep of the National League Championship Series, and during the seven-game World Series triumph over Milwaukee, he drove in eight runs.

Hernandez was performing well on the field but his attitude and off-field troubles marked him as trouble in the eyes of Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog. The root of the problem was cocaine. A 2010 article on the Bleacher Report website said, “Hernandez stated that he had used massive amounts of the substance starting in 1980 after he and his wife separated. He developed what he described as an ‘insatiable desire for more’ and admitted that he played under the influence of cocaine in his career.”2 The Cardinals decided that Hernandez was causing more problems than what he was worth to them, and on June 15, 1983, traded him to the Mets for pitchers Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. Amid the controversy, Hernandez’s play stayed sharp; he batted .306 in 95 games for a dismal Mets team and won his sixth consecutive NL Gold Glove.

The Mets were a team struggling to stay relevant in their division, winning only 41 games in 1981 and winning fewer than 70 per season from 1977 to 1983. Hernandez believed that was why he was traded to the Mets. “Whitey thought he was going to bury my ass in New York when he traded me here,” Hernandez said. “He had no idea what the minor-league system was like. He thought he was going to stick me here to suffer for two years. Didn’t happen. There was such a wealth of talent. And it was just amazing to see it all come together in ’84. It revitalized my career.”3

Upon Hernandez’s arrival in the Big Apple, he was bound and determined, along with manager Davey Johnson, to make the Mets a legitimate contender for a championship. In 1984, Hernandez’s first full season with the Mets, he made an impact, batting .311 with 15 home runs and earning a spot on the National League All-Star team for the first time since 1980. He won another Gold Glove and a Silver Slugger Award and finished second to Ryne Sandberg in the National League MVP voting. That season the Mets won 90 games, 22 more than they had won the previous season. They finished second in the NL East, the first time they had finished higher than fifth since 1976. Hernandez’s efforts (combined with the maturing of Darryl Strawberry and the arrivals of rookie pitchers Dwight Gooden, Ron Darling, and Sid Fernandez) proved to be the spark that the Mets were looking for.

In 1985 the Mets proved to the rest of the baseball world that they were for real. They won 98 games and finished second to the Cardinals in their division. In 158 games Hernandez batted .309 with 91 RBIs, and had a .997 fielding percentage.

Though the Mets had finally turned the page on their misfortunes, there was some uncertainty at the beginning of the 1986 season. Hernandez was a target in a massive investigation of drug use by major-league players. On March 1, Commissioner Peter Ueberroth suspended Hernandez and seven other players for a year, but offered to lift the suspensions if the players agreed to take a number of steps, including contributing 10 percent of their salaries to antidrug programs and undergoing drug tests for the rest of their careers. Hernandez at first said he would appeal, but then changed his mind so he could play the 1986 season. “’I feel strongly that I have an obligation to my team, the fans and to baseball to play this year,” he said. “… I hope this finally puts this issue to rest.”4 Hernandez proceeded to bat .310 (fifth in the league) with 83 RBIs. His 94 walks led the National League, he won his ninth consecutive Gold Glove, and he was voted a starter in the All-Star Game for the first time. Hernandez’s performance helped propel the Mets (108-54) to a first-place East Division finish. Assessing his role on the team, Hernandez said, “’I’ve played 12 years, and if you don’t know pitchers by then, and where to play against different hitters, then you haven’t learned anything. I don’t have the raw talent of other guys. I have to be prepared.”5

The 1986 postseason was Hernandez’s second career playoff appearance, and he looked to duplicate what he and the Cardinals had done during the 1982 postseason. The Mets’ first challenge would be to defeat the West Division champion Houston Astros, no easy task. Their offense was led by MVP runner-up Glenn Davis, while the anchors of the pitching staff were two former Mets —future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan and Cy Young Award winner Mike Scott. But the Mets vanquished the Astros in six games, the clincher a 16-inning classic, and advanced to the World Series against the Boston Red Sox. Hernandez had seven hits and three RBIs in the six NLCS games.

Hernandez started the World Series slowly at the plate, with just one hit in the first two games as the Mets lost both games. In their 7-1 victory in Game Three, he collected two hits and a walk, and scored a run. As the Mets forced a deciding Game Seven with their improbable extra-inning victory in Game Six, Hernandez had a hit and a walk.

The Mets fell behind, 3-0, in Game Seven, but Hernandez drove in two runs with a single in the sixth, and the Mets got another run to tie the game, 3-3. In the seventh, the Mets scored three more runs, the third one on a sacrifice fly by Hernandez. The Red Sox rallied, but the Mets hung on for an 8-5 victory and the world championship.

Hernandez was 33 years old at the 1987 season began. He played four more seasons, three with the Mets and a final season with the Cleveland Indians. He made his final All-Star team in 1987. During the 1989 season Hernandez’s skills began to fade dramatically; he hit just .233 with four home runs, due partly to a broken kneecap, suffered in a collision with Dave Anderson of the Los Angeles Dodgers, that sidelined him for eight weeks from mid-May through mid-July.6 After the season the Mets let Hernandez go in free agency and he signed with the Cleveland Indians for $3.5 million over two years. “This is a new league, a new city, a new stadium and a new challenge,” Hernandez said. “The Indians pursued me more than anyone else. It’s important to me to be wanted.”7 But his time in Cleveland was a bust; he played in only 43 games in an injury-plagued 1990 season. He announced his retirement before the season’s end. He then had back surgery in 1991.

Hernandez began to seek out ventures that would help promote his celebrity. Most notably he guest-starred in several episodes of the TV comedy Seinfeld. While Hernandez did not say much, his presence alone was enough to make the episodes instant classics. He told the New York Post, “Saying ‘I’m Keith Hernandez’ is still worth a lot of money.” (As of 2015 he was still receiving royalty checks for the Seinfeld appearances.8) Hernandez starred in The Boyfriend: Part 1 and The Boyfriend: Part 2, then came back for the series finale in 1998. The royalties for that continued, too. He also made commercials for the Just for Men hair dye product line, including a series of laugh-inducing ads with former New York Knicks star legend Walt Frazier.9

In 2000 Hernandez began tutoring Mets first basemen in spring training. In 2006 he started a second career, doing color and commentary on Mets game telecasts on the SNY cable channel. Hernandez said he was a reluctant recruit to the announcing booth but felt he had to do something productive. He became known for being direct and opinionated about the “young men” on the diamond.10

Hernandez also took part in Mets community events. In 2012 he arranged to shave off his trademark mustache at an event for charity. It attracted 300 fans and raised $10,000 for a Brooklyn day care center for Alzheimer patients. Hernandez chose this charity because his mother, Jacquelyn, died of Alzheimer’s disease in 1989.11

Hernandez was inducted into the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame on August 21, 2021. On July 9, 2022, the Mets retired Hernandez’s jersey no. 17. During his speech, Hernandez said, “I realized that I had to set an example of how I conducted myself on and off the field, and I embraced that…It’s a team. I always felt myself as just a player, one of 25. Nothing special about me, just one of the guys, having a great time and working hard for a championship.”12

Hernandez has been married twice and has three children from his first marriage. As of 2015 he lived in Sag Harbor, New York. Of his post-baseball career, he said, “I mean, how bad is this? I am paid handsomely, with six months off, and it’s baseball. Not bad, right?”13

Last revised: April 13, 2023 (zp)

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and Hernandez’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 William Berlind, “Keith Hernandez, Hero of ’86 Mets, Navigates His Life after Baseball,” observer.com/1999/07/keith-hernandez-hero-of-86-mets-navigates-his-life-after-baseball/, July 19, 1999.

2 Harold Friend, “Keith Hernandez Used Cocaine and Was Forced to Name Others,” Bleacher Report, February 17, 2010. bleacherreport.com/articles/1070283-keith-hernandez-used-cocaine-and-was-forced-to-name-others.

3 Berlind.

4 Joseph Durso, “Hernandez Won’t Challenge Ueberroth,” New York Times, March 9, 1986.

5 Craig Wolff, “Hernandez Blends Instinct and Savvy,” New York Times, October 8, 1986.

6 Joseph Durso, “Hernandez Fractures Kneecap; Out 8 weeks,” New York Times, May 19, 1989.

7 Joseph Durso, “Hernandez Is Signed by Indians for Two Years,” New York Times, December 8, 1989.

8 Zach Braziller, “Keith Hernandez Still Lining His Pockets with Seinfeld Money,” New York Post, June 16, 2015; Ron Dicker, “Keith Hernandez Says He Gets $3,000 in Royalties for Seinfeld,” Huffington Post, June 16, 2015.

9 Richard Sandomir, “Just for Men Just Right for Former Stars,” New York Times, January 6, 2008.

10 Michael Powell, “Driving to Work with Keith Hernandez, the Real Mr. Met,” New York Times, September 28, 2015.

11 Joseph Berger, “Farewell to a Mustache Forever Linked to the Mets,” New York Times, September 27, 2012.

12 Mojo Hill, “Mets Honor Keith Hernandez With Number Retirement Ceremony,” Metsmemorized Online, https://metsmerizedonline.com/mets-honor-keith-hernandez-with-number-retirement-ceremony/ (last accessed July 29, 2022)

13 Powell.

Full Name

Keith Hernandez

Born

October 20, 1953 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.