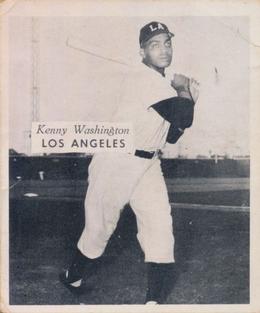

Kenny Washington

Kenny Washington, known to many as the Jackie Robinson of the National Football League and one of the greatest players in football history, was also a standout on the diamond. Various people who saw him play baseball thought his talent surpassed Robinson’s. On three separate occasions Washington figured in efforts to integrate professional baseball.

Kenny Washington, known to many as the Jackie Robinson of the National Football League and one of the greatest players in football history, was also a standout on the diamond. Various people who saw him play baseball thought his talent surpassed Robinson’s. On three separate occasions Washington figured in efforts to integrate professional baseball.

Kenneth Stanley Washington was born August 31, 1918, the only child of Edgar and Marion (Lenàn) Washington. Edgar Washington, also known as “Blue,” played parts of two seasons with Negro League clubs. In 1916 he pitched briefly for Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. In 1920, the inaugural season of the Kansas City Monarchs, Washington opened the campaign as the club’s first baseman but was released in mid-June. Washington’s thoroughly irresponsible parents’ partying rendered them frequently absent from his life. Accordingly, he was raised by his paternal grandmother, Susie Washington, while his uncle, Roscoe Washington, filled a paternal void.

Though best known for his football exploits, Washington first gained acclaim in baseball. During the spring of 1934 – playing shortstop for Lincoln High School in Los Angeles – Washington, just a sophomore, dueled another sophomore sensation: Bobby Doerr of Fremont High. The two contested the Los Angeles City batting title as their teams fought for the city championship. When their schools met on May 22, both hit home runs in a game Washington’s side won, 2-1.1 A polio outbreak in the final weeks of the season led city leaders to ban public gatherings,2 bringing the high school baseball season to an early halt. In its aftermath, the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News selected Washington as the all-city shortstop while Doerr was a second team selection.3

While several high school opponents signed professional contracts, and three rivals – Jimmy Direaux, Lloyd Summers, and Walter Gooch – joined Negro League teams, Washington accepted a scholarship to play football at UCLA.4 On the gridiron Washington fueled the Bruins’ rise to prominence. His right arm was so strong that in the 1937 USC game (a 19-13 UCLA loss) Washington heaved a pass 72 yards, which at the time was a college football record. In 1939 he teamed with a junior college transfer, Jackie Robinson, in the UCLA backfield. Washington led the nation in total yardage and became the first UCLA football player chosen as a first team All-America. He won the Fairbanks Award as the 1939 college football player of the year and led the Bruins to their first undefeated season along with a number 7 national ranking.

During the spring of his sophomore year at UCLA, Washington became the first of his race to play varsity baseball at the school. He possessed a throwing arm his teammate Al Martell called “like a howitzer.”5 Martell added that Washington was “one of the most powerful hitters I’ve ever seen, college or pro.”6 Washington hit .397 for the season, .409 in California Intercollegiate Baseball Association games, and was named the all-league shortstop.7 He led the Bruins with 4 home runs and 19 runs batted in during their 17-game season.8 In a March game at Stanford, Washington sent a towering blast over a tree behind the 425-foot sign on the right-center field wall. Observers called it the longest home run ever hit out of the Stanford ballpark.9 Washington’s play moved San Francisco Examiner columnist Prescott Sullivan to write, “Leading hitter, best shortstop in the college baseball out our way is Kenny Washington. Coaches of other teams say he has major league ability. But big-league scouts aren’t interested in him. Washington is a Negro.”10

Rather than play baseball as a UCLA junior, Washington opted for a job at Warner Brothers Studios, arranged by his football coach, either the exiting William Spaulding or the incoming Babe Horrell. When he signed up to play professional football for the Hollywood Bears in the newly formed Pacific Coast Professional Football League in August 1940, most felt Washington had picked up a baseball glove and bat for the last time. Washington’s separation from the game lasted four years, until October 1942.

Dating back to 1920, Los Angeles had been home to a thriving winter baseball league. Its founder, Joe Pirrone, began each season with an exhibition game in either the Los Angeles Angels’ park, Wrigley Field, or the Hollywood Stars’ ballpark, Gilmore Field. The game featured a team of players from American, National, and Pacific Coast League teams against a team made up of Negro League players. When, in 1942, a handful of Negro League players could not make it to Los Angeles in time for the game, Pirrone turned to Kenny Washington to fill in. Inserted at second base and third in the batting order for the Philadelphia Royal Colored Giants, Washington came up in the bottom of the first inning and sent a pitch from Brooklyn Dodgers lefty Larry French to the last row of the Wrigley Field bleachers in right center field.11 When years later Washington was asked his greatest thrill in sports, he cited the blast, calling it, “thrill enough to last for a life-time.”12 Washington added a double later in the game. He was invited to join the team again the following Saturday and went three-for-three with two doubles and a single.13

Washington was turned down by the military for service in World War II because of football injuries and a young family. He had married his college sweetheart, June Bradley, in September 1940. The following year the couple had a son, Kenneth Stanley Washington Jr. In 1957 they adopted an infant daughter, Karin. In May 1942 Washington joined the Los Angeles Police Department. Soon after, the department created a baseball team, which traveled the state playing games against other law enforcement, military, and college teams. Washington produced headlines with his slugging. He hit a home run reported to have traveled 450 feet in a win over a team in El Segundo.14 His grand slam beat his alma mater, UCLA.15 Washington hit two long doubles against a Navy team with a lineup of veteran Negro League players.16 When the LAPD nine played the Santa Ana Army Air Base team in June 1943, the game drew widespread attention because it featured Washington and Joe DiMaggio. Though DiMaggio’s side came away victorious, 10-3, Washington garnered headlines with a long first-inning home run, while DiMaggio had a single in three at-bats.17

Washington became a figure in efforts to integrate professional baseball three times. The first came four weeks after his final football game at UCLA. A sportswriter, Dave Farrell, seized on the arrival in Southern California of Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Larry McPhail. Through his column he urged the Dodgers’ executive to sign Kenny Washington and Jackie Robinson. “These two lads are too good to be kept out of baseball for long,” Farrell wrote. “If you don’t sign them somebody else will.”18 Farrell received no reply.

Washington became a figure in efforts to integrate professional baseball three times. The first came four weeks after his final football game at UCLA. A sportswriter, Dave Farrell, seized on the arrival in Southern California of Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Larry McPhail. Through his column he urged the Dodgers’ executive to sign Kenny Washington and Jackie Robinson. “These two lads are too good to be kept out of baseball for long,” Farrell wrote. “If you don’t sign them somebody else will.”18 Farrell received no reply.

Three years later, with America at war and more than 1,400 minor-league players serving their country, several Pacific Coast League clubs approached spring training in need of players. Editors of two African American newspapers, the Los Angeles Sentinel and California Eagle, proposed a solution to the Hollywood Stars and Los Angeles Angels – Kenny Washington, along with several Negro League players who worked at Los Angeles-area aircraft factories and munitions plants.19 Clarence “Pants” Rowland, business manager of the Angels, said his team was open to giving Washington a tryout. “If a man is capable of playing in this league, he will be signed and paid accordingly,” he said.20 When spring training arrived and a tryout invitation didn’t, Rowland was pressed for an answer. He said the Angels’ manager, Bill Sweeney, objected to the idea. Sweeney told the newspapermen the addition of a Black player or players would cause friction on his ballclub.21

In Oakland, Oakland Tribune columnist Art Cohn pushed the idea of the Pacific Coast League’s Oaks signing Kenny Washington. Cohn wrote that Washington “would be a tremendous asset to any Coast League club both on the field and at the box office.”22 The club declined.

On October 23, 1945, at the direction of Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey, Jackie Robinson signed a groundbreaking contract with the Montreal Royals. Robinson would integrate minor-league baseball. Rickey’s plan called for not just Robinson, but two Black players to play for the Dodgers’ farm club for the 1946 season. Robinson lobbied for his friend and former UCLA teammate. Robinson told the New York Daily News, that Washington would “make his first serious crack at baseball next year.”23 Wendell Smith, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, added his endorsement. In a letter to Rickey, Smith wrote, “I am suggesting you consider very seriously the possibility of Kenny Washington, who was Jackie’s team-mate at UCLA. I understand that he is a much better ball player than Robinson.”24

When asked if he would switch sports, Washington told a reporter, “I answered no because I had other plans.”25 At the time those plans were shrouded in secrecy. On January 12, 1946, the NFL champion Cleveland Rams declared their intention to move to Los Angeles. During a quick trip to Los Angeles four days later, Rams general manager Chile Walsh instructed his new public relations director, Maxwell Stiles, to meet with Washington and get an agreement that he would join the team. The matter was to be kept in strict confidence until Walsh returned to Los Angeles in March, at which time the agreement would be formally announced.26 In fact, at their first news conference in Los Angeles on March 21, 1946, the Rams announced the signing of Kenny Washington and an end to 12 years of segregationist practices in the National Football League. As much as he aspired to play professional baseball, Washington, ever a man of his word, told a reporter, “I couldn’t go back on it.”27

Late in Washington’s rookie NFL season, Leo Durocher told Los Angeles sportswriter John B. Old that the Dodgers might sign Washington.28 Over the next several weeks, stories claiming an imminent signing appeared in several newspapers around the country.29 Prior to the start of spring training, Durocher said the Dodgers’ scouts were concerned about a knee injury Washington had suffered on the gridiron and recommended against his signing.

Washington retired from football in December 1948, after his third season with the Rams. Almost immediately baseball reentered the picture. Famed entertainer Bing Crosby, a part-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, offered Washington a shot with his ballclub.30 The San Diego Padres extended an offer as well.31 Washington declined both offers. Once again it was a case of honoring prior commitments. Washington had accepted offers to act in three movies.

After concluding work in Rope of Sand, Pinky, and The Jackie Robinson Story, Washington declared that he would turn his full attention to baseball. For almost two months he spent five days a week training. Before the start of spring training in February 1950, Leo Durocher – by then managing the New York Giants – offered Washington a chance with the Giants. “I’m anxious to see Kenny play. I hope he can make it,” Durocher said.32

Washington faced enormous obstacles. He was 31, the oldest rookie in any 1950 spring training camp. He hadn’t played competitive baseball in almost seven years. His body had taken a beating from football, necessitating five knee operations among other difficulties. Durocher said his roster was largely set. The only open job was for one outfielder. From his pool of candidates, Durocher had to settle on a starter in right field. Washington would compete for the spot with Monte Irvin, Don Mueller, and Pete Milne.33

In the Giants’ first intra-squad game, Washington clubbed a long home run off Dave Koslo.34 When exhibition games began, Washington was the Giants’ right fielder. He was held hitless in two games with Cleveland, then assigned to the Giants’ B team. Late in the spring, during an exhibition game with the University of Southern California, Washington came up with two teammates on base and belted a triple. In the eighth inning, Washington came to bat with the bases loaded and sent a ball over the right center field fence for a grand slam.35

Not long after, however, Durocher informed Washington that he would not make the team. “All those years of football took too much out of him,” a scout who wished to remain anonymous told Frank Finch of the Los Angeles Times.36

Armed with a recommendation from Durocher, Washington joined the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League on the eve of Opening Day. He debuted the following night as a pinch-hitter against San Diego lefty Roy Welmaker. After a pair of long foul balls, Washington whiffed on a curve. It was a sign of things to come. In the Angels’ 24th game of the season Washington was made the team’s third baseman.37 Two nights later, while covering the bag on a stolen base attempt, he was badly spiked.38 When the Angels suggested he go to a lower level of the minor leagues to try to regain his batting eye, Washington opted instead to retire from professional sports. In six games Washington had failed to get a hit in nine trips to the plate.

Washington became an executive with Young’s Market, the largest wholesale liquor distributor in Los Angeles. In 1958 Walter O’Malley recruited Washington to serve as a consultant to the newly moved Los Angeles Dodgers. He aided the business department and Dodgers scouts.39 When the Dodgers succeeded in landing one of the most coveted amateur players in the country – Willie Crawford – in June 1964, sportswriters pointed out that Washington played a major role in the coup.40

On June 24, 1971, Kenny Washington succumbed to polyarteritis, a rare and incurable heart disease. He was 52 at the time of his death. Washington was laid to rest in Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles. In all, four generations of Washingtons would play professional baseball. Kenny Jr. was a standout on the 1963 national championship team at the University of Southern California. He spent six seasons in the Dodgers farm system, briefly getting as high as Class AAA, and played part of the 1970 season with the Nankai Hawks in Japan. Two of Kenny Washington’s grandsons, Kirk and Kraig, played professionally in the Chicago Cubs organization (1986 and 1988-90, respectively).

Reflection has left many to wonder what might have been if Washington hadn’t been barred from professional baseball because of his race when he left UCLA in 1940. College rival Frank Peterson said, “If it hadn’t been for the color line, he’d have made it to the majors before Robinson or any of them. He was better than Robinson when I saw him play in college.”41

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Kenny Washington’s daughter, Karin Cohen, and his grandson, Kirk Washington, for their assistance.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Rod Nelson.

Sources

Websites

Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, IMDB.com, Newspapers.com, and Paperofrecord.com.

Books

Dan Taylor, Walking Alone: The Untold Journey of Football Pioneer Kenny Washington. Lanham, Maryland; Rowman and Littlefield (2022).

NCAA Football’s Finest. Indianapolis: National Collegiate Athletic Association (2002).

Notes

1 “Lincoln Edges Out Fremont Team, 2-1,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1934: 28.

2 “Prep Moguls Cut Baseball Season Short,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 1934: A9.

3 Stanley Speer, “Prep Pick Ups,” Hollywood Citizen-News, June 21, 1934: 17.

4 “Direaux to Twirl,” Los Angeles Times, December 24, 1936, 15.

5 Maxwell Stiles, “Styles in Sports,” Los Angeles Mirror-News, February 18, 1956: 21.

6 John Hall, “The Story Teller,” Los Angeles Times, November 7, 1972: 37.

7 “Kenny Washington Home Run King; Brewer Best Hurler,” Hollywood Citizen-News, May 26, 1938: 8.

8 Milt Cohen, “Carter Leads as Final Bruin Batting Averages Released,” California Daily Bruin, May 11, 1938: 3.

9 Braven Dyer, “The Sports Parade,” Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1938: 31.

10 Prescott Sullivan, “Low Down,” The San Francisco Examiner, April 8, 1938: 22.

11 All-Stars Top Colored Giants,” Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1942: 20.

12 Kenny Washington as told to Herman Hill, “My Greatest Thrill,” The Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania)Courier, May 15, 1943: 19.

13 “Larry French, Jess Flores Beats Giants,” Los Angeles Times, October 19, 1942: A11.

14 “Washington Homers as Police Team Wins,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1943: 16.

15 Al Wolf, “Sportraits,” Los Angeles Times, February 25, 1943: 30.

16 “Police Nine Lose to Navy Team,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 1, 1943: 18.

17 “DiMag Hits in 13th Tilt as Flyers Win,” Oakland Tribune, June 3, 1943: 30.

18 Dave Farrell, “Asks McPhail to Sign Negro Stars for Good of the Game,” The Pittsburgh Courier, March 30, 1940: 17.

19 “Three Players Barred After Promise of Try with Angels,” The Pittsburgh Courier, March 27, 1943: 18.

20 Herman Hill, “’Will Give Negro Players Trial on Club,’ says Mogul.” The Pittsburgh Courier, February 6, 1943: 18.

21 Art Cohn, “Cohn-ing Tower,” Oakland Tribune, April 13, 1943: 24,

22 Cohn, “Cohn-ing Tower.”

23 Jimmy Powers, “The Power House,” New York Daily News, November 22, 1945: 116.

24 Wendell Smith, letter to Branch Rickey, December 19, 1945.

25 Roger Birtwell, “Air Duel Looms as Yanks Battle NFL Champion Rams,” Boston Globe, November 24, 1946: 24.

26 Maxwell Stiles, “Styles in Sports,” Hollywood Citizen-News, June 28, 1967: 2.

27 “Kenny Washington Dies, Pioneered Blacks in NFL,” Miami (Florida) Herald, June 26, 1971: 138.

28 “Washington May Be Inked by Brooklyn Says Leo Durocher,” California Eagle, November 21, 1946: 17.

29 Sam Lacey, “Looking ’em Over,” The Richmond (Virginia) Afro-American, January 4, 1947: 4

30 Dan Burley, “Dan Burley on Sports,” New York Age, January 29, 1949: 12.

31 Paul Zimmerman, “Sportscripts,” Los Angeles Times, January 6, 1949: 51.

32 “Kenny Washington Sure He Can Make the Grade,” The Pomona Progress Bulletin, February 27, 1950: 12.

33 Frank Finch, “Washington to Report for Trial with Giants,” Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1950: 58.

34 “Kenny Washington Hits Homer; Giants’ Stanky Taps 3-for-4,” San Bernardino Daily Sun, March 6, 1950: 18.

35 Frank Finch, “Kenny Uses Bat to Wallop His Former Football Rivals,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1950: 9.

36 Frank Finch, “Scouting the Pros,” Los Angeles Times, March 19, 1950: 86.

37 “Angels Slug Out Win Over Padres,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 1950: C1.

38 “Angels Take Padre Series; Hollywood Now at Wrigley,” Los Angeles Sentinel, April 27, 1950: B8.

39 “Kenny Washington Signed as a Scout,” The Billings (Montana) Gazette, November 21, 1958: 11.

40 Edw. “Abie” Robinson, “Crawford’s Signing Called Smart Move,” California Eagle, June 25, 1964: 8.

41 Steve Sneddon, “From My Corner,” Reno (Nevada) Gazette-Journal, June 26, 1971: 7.

Full Name

Kenneth Stanley Washington

Born

August 31, 1918 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

June 24, 1971 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.