Luke Appling

Luke Appling had the misfortune of playing for the White Sox during some of their leanest years. A decade before his arrival, the franchise had been devastated by the Black Sox Scandal, when eight players conspired to fix the 1919 World Series and were banned from baseball, and the team did not compete again until the 1950s. Appling, a happy-go-lucky man and a notorious hypochondriac, was one of the Sox’ few bright lights. He never got to play in a World Series, as his career was ending just as the team embarked on a period of competitiveness highlighted by their 1959 pennant.

Luke Appling had the misfortune of playing for the White Sox during some of their leanest years. A decade before his arrival, the franchise had been devastated by the Black Sox Scandal, when eight players conspired to fix the 1919 World Series and were banned from baseball, and the team did not compete again until the 1950s. Appling, a happy-go-lucky man and a notorious hypochondriac, was one of the Sox’ few bright lights. He never got to play in a World Series, as his career was ending just as the team embarked on a period of competitiveness highlighted by their 1959 pennant.

At a time when America, along with the rest of the world, was struggling to cope with the worst depression in its history and the ominous rise of fascism in Europe, baseball provided some diversion from dark times. Appling started his major league career in 1930, just about the beginning of the Depression. The best word to describe Luke Appling is durability, a quality he showed throughout his baseball career and his life. He was emblematic of an America struggling through the Depression and digging into their psyches (perhaps unknowingly) to prepare for another world war. Appling endured and so did America.

“Old Aches and Pains,” as Appling was called, was arguably the greatest hypochondriac to ever play the game. Backaches, headaches, bad knees, eye problems would torment him-and then he’d go out and get three hits.

Lucious Benjamin Appling, born in High Point, North Carolina, on April 2, 1907, was clearly no slouch when he took the field. All of his medical complaints disappeared when game time came. He was so infirm that he managed to collect only 2,749 hits in a career that spanned twenty years, all with the Chicago White Sox. Appling never let a backache or headache get in the way of playing shortstop and getting in his licks as a hitter. He even complained about field conditions at Comiskey Park. “I swear that park must have been built on a junkyard,” he exclaimed. It turned out later he was right.

Appling attended Fulton High School in Atlanta and spent two years at Oglethorpe College. In 1930, when he was a sophomore at Oglethorpe, he signed with the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. He hit the ball solidly for the Crackers, but his fielding at shortstop left something to be desired, as he committed 42 errors.

Late in the 1930 season the Atlanta Crackers were sold to the Chicago Cubs. But due to the intervention of Milt Stock, Appling joined the White Sox in a cash transaction that also involved an outfielder named Doug Taitt. Despite his fielding woes the White Sox bought his contract for $20,000. Appling made his debut for the White Sox at the end of the 1930 season. Appearing in six games, he committed four errors but also collected eight hits. He had a strong arm, but many of his throws ended up in the stands, sending fans scurrying out of the way.

The 1931 season was less than stellar for Appling. His fielding troubles still plagued him, and his hitting fell off. The White Sox tried to trade him, but there were no takers. White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes took Appling in hand and with great patience helped Appling polish his fielding skills and had him stop swinging for the fences.

Appling married Faye Dodd in 1932. They had two daughters (Linda and Carol) and one son (Luke III).

In 1932 the Pale Hose finished in seventh place behind the lowly St. Louis Browns. Appling batted .274 with ten triples and 63 runs batted in. He still was swinging for the fences and got himself out innumerable times through his lack of patience at the plate.

It all came together for Luke Appling in 1933, when he stopped trying to hit home runs, learned to use the entire field, and batted .328 for the season. Eight more years of .300 or better followed, and he improved enough to become an adequate fielder. He showed great range in the field, leading the American League in assists seven times. On the minus side he led the league in errors five times.

The apex of his career came in 1936. He won the American League batting title with a .388 batting average, the highest in the twentieth century by a shortstop. Luke also had a 27-game hitting streak that year. After winning the batting title, Appling was promised a $5,000 bonus, but General Manager Harry Grabiner reneged. In disgust Appling tore up his 1937 contract. Lou Comiskey, the owner, withstood Appling’s protests, and when Appling cooled down and was ready to play gave him a new contract. Unfortunately, it was for $2,500 less than he had wanted. In 1940 Appling, Rip Radcliff of the St. Louis Browns and Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees battled each other for the batting title with DiMaggio winning out.

The White Sox contended only once during Appling’s tenure at short. They lacked power, so Appling, a natural leadoff hitter, batted third in the lineup. Never a slugger, he did manage to drive in 1,117 runs during his career. Appling remembered that his teammates were not great baserunners. Player-manager Jimmy Dykes instituted an automatic fine for any baserunning blunders. The very next day Dykes was on second base when he became lost in thoughts about his managerial duties. He wandered off second base, wondering whether he should hit for the pitcher, and in a flash he was picked off. The players on the bench howled with delight and had some uncomplimentary words about the gaffe. When Dykes sheepishly returned to the bench he said, “All right say it, come on, I’ve got it coming,” but no one said a word. Later he asked Appling why they didn’t say anything. Appling replied, “They already said it before you got back to the dugout.”

Championships eluded the White Sox and the Cubs year after year. Ironically, the two greatest players in Chicago, Luke Appling and Ernie Banks, both shortstops, never played in a World Series.

Appling was a pitcher’s nightmare. He could and would foul off pitch after pitch until he got the one he wanted. Pitchers would get so frustrated they’d almost dare him to hit the blasted thing. Appling struck out only 528 times in his career and coaxed out 1,302 walks.

As one story goes, Appling once asked the tight-fisted business manager of the Sox for several balls to sign for friends. The business manager refused, citing the Depression and that each ball cost $2.75. Appling turned and walked out without a word. That afternoon in his first at bat he fouled off ten consecutive pitches into the stands. Turning to the club official in the owner’s box, he said, “That’s $27.50 and I’m just getting started.”

In 1938 the Sox had a chance to beat out the Yanks for the pennant. However, Appling suffered the only major injury of his career when he fractured his ankle, thereby hampering the chances of the club.

DiMaggio got a break during his 56-game hitting streak in 1941 when he hit a slow roller that bounced up on Luke. Joe was given a hit on the play to keep his streak going at 30 games.

Bill James in The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract named Luke Appling the best player of the 1943 season as Appling won his second batting title with a .328 average. Of course, 1943 was a war year and most of the stars were in the service.

Teammate Ted Lyons recalled Appling’s ability to foul off pitches until he got the one he wanted. Red Ruffing was pitching for the Yankees against the Sox on a miserably hot, humid day in Comiskey Park. Appling came up with two men on base and worked the count to 3-2. He then proceeded to foul off 12 pitches in a row. The profusely sweating Ruffing finally walked Appling and gave up a grand-slam homer to the next batter. Ruffing was in a cool shower immediately after. Pitchers considered themselves lucky if Appling got a hit early in the count.

Despite all his alleged ailments Appling was a good-natured person and popular with his teammates. The only White Sox player to win a batting championship until Frank Thomas, he was also voted the greatest White Sox living player by Chicago writers in 1969.

Appling entered the service in 1944 and returned to baseball late in 1945. At the time Appling entered the service his wife said, “The war will be over soon. Luke has never held a job for more than two weeks outside of baseball.” His hitting did not suffer when he returned in 1945. He batted .368 in his shortened season.

Appling was still playing ball at age 41, having been moved to third base from his shortstop position. Before a doubleheader in 1948 he complained of not being able to get his throwing arm loose. In the first game he lashed out three hits and with a supposedly crippled arm set an American League record with 10 assists. Before the nightcap he complained of severe pains in his legs and went out and did a sterling job.

In 1949 he batted .301 at the age of 42, but “Trader” Frank Lane, general manager of the White Sox, was committed to a youth movement, and Chico Carrasquel took over at shortstop. Appling helped Carrasquel adapt to the big leagues and at playing shortstop. Appling was asked to play first base, but after a few lackluster attempts he gave it up and filled in as a utility infielder. He played in 50 more games for the White Sox in 1950 and then retired. At the time of his retirement he held the American League records for most games played, assists, putouts and chances accepted by a shortstop. Appling also eclipsed the major league record for most games played at shortstop previously held by Rabbit Maranville. Maranville had played 2,153 games at short, and Appling exceeded that with 2,198. Luis Aparicio later eclipsed most of these records. Appling is still the club leader in runs, games played, hits, doubles, total bases, runs batted in, walks, and at bats; he’s also third in triples. In 1951 Appling was asked to manage the Memphis Chicks and surprised everyone including himself when he accepted.

The quality that emerges from Appling’s career and character is his durability. Maybe his ailment complaints were his way of exorcising the demons that baseball players (probably the most superstitious athletes to play sports) exhibited. Whatever his secret, his major league career spanned twenty years. Long after his retirement he showed he could still hit when in an appearance in a Cracker-Jack All-Star Old-Timers game in Washington, D.C., at the age of 75 he hit a homer off Warren Spahn. He said, “It was a good pitch and I just swung away.” The ball traveled only 250 feet as the fences were moved in for the old-timers game, but it’s still a good distance for a 75-year-old.

Appling managed in the minors for quite a few years, winning pennants for Memphis in the Southern Association and Indianapolis of the American Association. Named Minor League Manager of the Year in 1952, he still had only one chance managing in the majors, at Kansas City replacing Alvin Dark. He was not very successful as his team went 10-30 during his tenure. He also managed at Richmond and coached in the majors at Detroit, Cleveland, Baltimore, and Kansas City. He served as batting instructor for the Braves until 1990.

Appling died suddenly from an abdominal aneurysm on January 3, 1991, in Cumming, Georgia. His wife Fay; a brother Clyde; sisters Dela Campbell, Inez Jones, and Marie Shelton; his three children; and six grandchildren survived him. Appling is buried in Sawnee View Memorial Gardens, Mausoleum Chapel West in Cumming.

Luke Appling was in the mold of most Depression ballplayers-tough, somewhat hard-bitten, often with lean faces that showed the rugged times all Americans were enduring. Happy to be playing ball when so many others were standing on street corners selling apples or standing in line for soup, they brought some relief to a nation back on its heels. Appling along with others helped take people’s minds off the Depression if only for a few hours and made life a bit more bearable. It was the endurance of players like Luke Appling who carried baseball through these troubled times and sparkled even in a time of misery and foreboding as the sound of cleats on the dugout steps would soon be muffled by the hobnailed boots of oppressors.

Photo credit

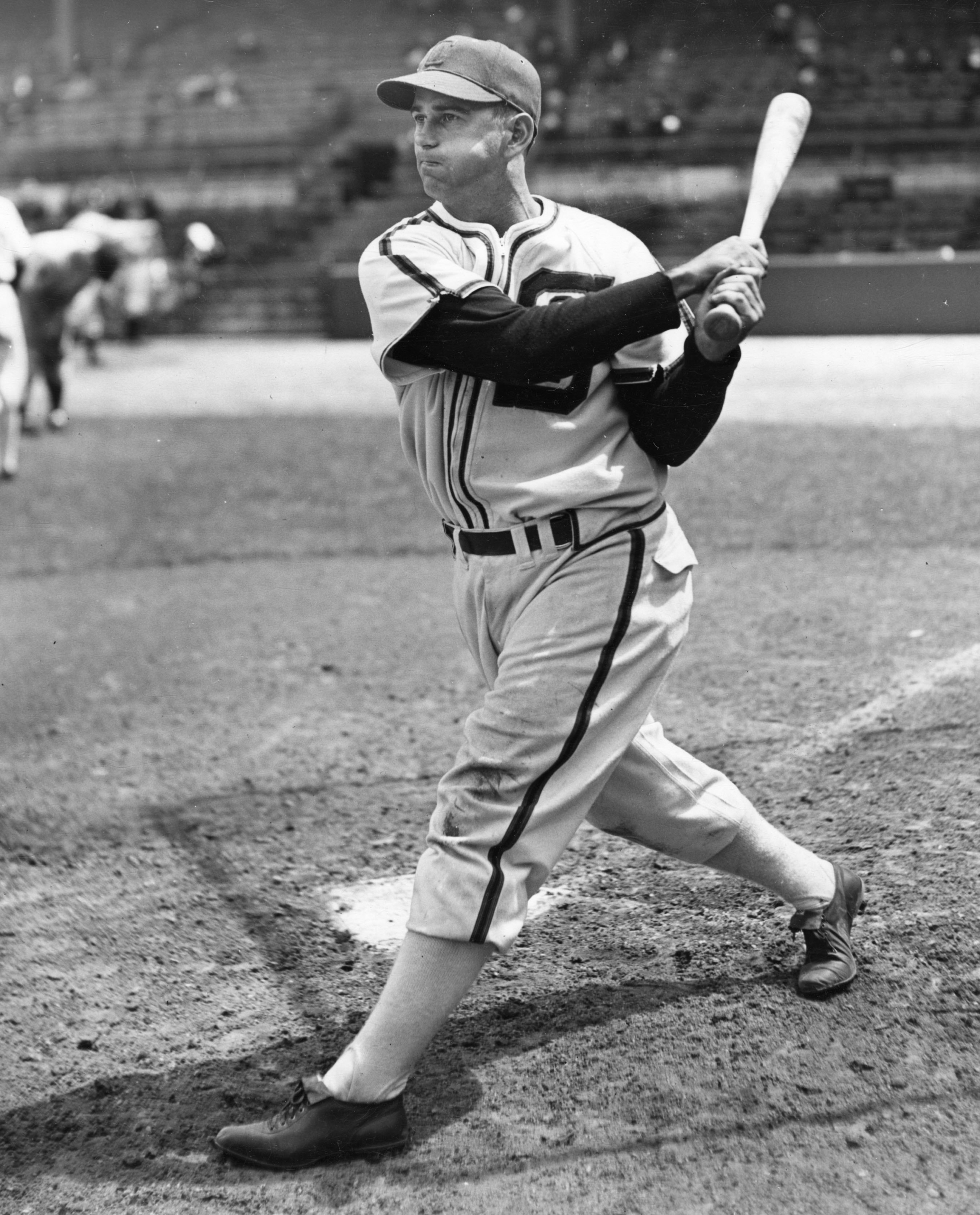

Luke Appling takes batting practice before a game at Comiskey Park in 1940. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Sources

Cataneo, David. Peanuts and Crackerjack. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1991

Creamer, Robert W. Baseball In 1941. New York: Penguin, 1991.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Baseball Historical Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

Luke Appling File at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Nemec, David, and Saul Wisnea. Baseball: More Than One Hundred Fifty Years. Lincolnwood, Illinois: Publications International, 1997.

Full Name

Lucius Benjamin Appling

Born

April 2, 1907 at High Point, NC (USA)

Died

January 3, 1991 at Cumming, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.